Click on the above“Linux Tech Enthusiast” and select “Set as Favorite”

High-quality articles delivered promptly

☞【Essentials】ChatGPT 4.0 is unlocked, no limit on questions!!!

☞【Essentials】Notes on Linux self-learned by a Tsinghua senior, top-level quality!

☞【Essentials】Comprehensive list of commonly used Linux commands, all in one article

☞【Essentials】Bookmark! Linux basic to advanced learning roadmap

1. Using Variables

1. Variable Naming

When defining a variable, do not add a dollar sign ($, which is required in PHP), for example:

your_name="yikoulinux"

Note that there should be no spaces between the variable name and the equals sign, which may differ from all programming languages you are familiar with. Additionally, the naming of variables must follow these rules:

-

Names can only use letters, numbers, and underscores, and the first character cannot be a number.

-

Spaces are not allowed in the middle; underscores (_) can be used.

-

Punctuation marks cannot be used.

-

Keywords in bash cannot be used (you can check reserved keywords with the help command).

-

Variable names are generally conventionally written in uppercase.

Examples of valid shell variable names:

RUNOOB

LD_LIBRARY_PATH

_var

var2

Examples of invalid variable names:

?var=123

user*name=runoob

2. Common Variables

In Linux Shell, variables are divided into system variables and user-defined variables.

-

System variables: HOME, PWD, SHELL, USER, etc. For example: echo $HOME, etc.

-

User-defined variables:

-

Defining a variable: variable=value

2) Display all variables in the current shell: set3) Unset a variable: unset variable4) Declare a static variable: readonly variable, note: cannot unset

-

Assign the return value of a command to a variable (key point)

In addition to explicitly assigning values, you can also assign values to variables using commands, for example:

A=$(ls -la)

$ is equivalent to backticks

3)

for file in `ls /etc`

or

for file in $(ls /etc)

The above command will loop through the filenames in the /etc directory.

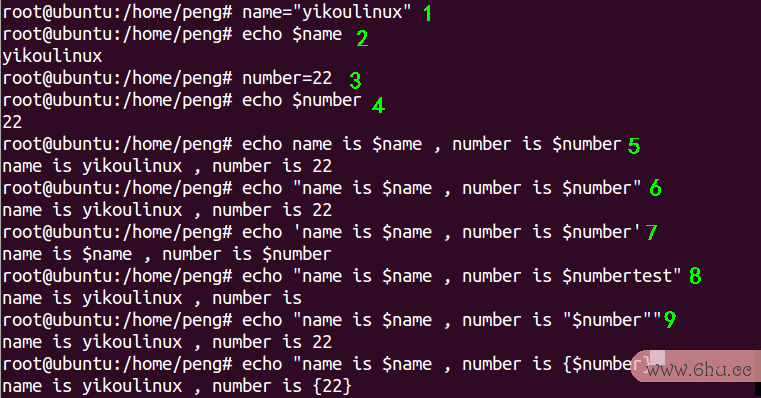

3. Example

Example 1: The meaning is as follows:

The meaning is as follows:

-

Define a variable named name with the value of “yikoulinux”

-

Output the value of the variable name

-

Define a variable named number with an initial value of 22

-

Output the value of the variable number

-

Directly output a string with variables

-

Use double quotes to output a string with variables

-

Use single quotes to output a string with variables

-

Use double quotes to output a string with non-existent variables; non-existent variables default to empty

-

Use double quotes to declare variables in a string

-

Use curly braces {&variable_name} to declare variables in a string

Note: The above variables are temporary; they will disappear when the terminal is closed.

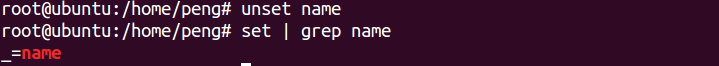

Example 2: Remove a variable and check a specified variable

-

unset name removes the variable name

-

Check the name variable

2. String Operations

When creating shell batch processing programs, string-related operations are often involved. Many command sentences, such as awk and sed, can perform various string operations.

In fact, the shell has a series of built-in operators that can achieve similar effects. We know that using internal operators saves time compared to external programs, so the speed will be very fast.

1. String Operations (Length, Read, Replace)

| Expression | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ${#string} | Length of $string |

| ${string:position} | Extract substring starting from position $position in $string |

| ${string:position:length} | Extract substring of length $length starting from position $position in $string |

| ${string#substring} | Remove the shortest matching substring $substring from the beginning of variable $string |

| ${string##substring} | Remove the longest matching substring $substring from the beginning of variable $string |

| ${string%substring} | Remove the shortest matching substring $substring from the end of variable $string |

| ${string%%substring} | Remove the longest matching substring $substring from the end of variable $string |

| ${string/substring/replacement} | Use $replacement to replace the first matching $substring |

| ${string//substring/replacement} | Use $replacement to replace all matching $substring |

| ${string/#substring/replacement} | If $string matches the prefix $substring, replace the matched $substring with $replacement |

| ${string/%substring/replacement} | If $string matches the suffix $substring, replace the matched $substring with $replacement |

Note: “* $substring” can be a regular expression.

2. Examples of String Operations

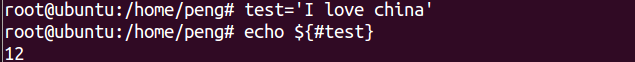

a) Calculate string length

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# test='I love china'

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${#test}

12

${#variable_name} gets the string length

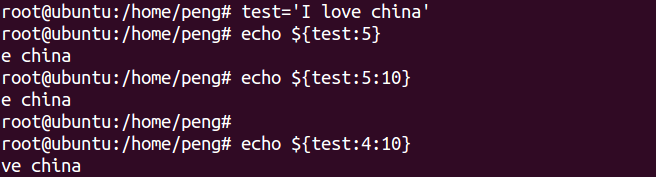

b) Substring extraction

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# test='I love china'

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test:5}

e china

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test:5:10}

e china

root@ubuntu:/home/peng#

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test:4:10}

ve china

${variable_name:start:length} gets the substring

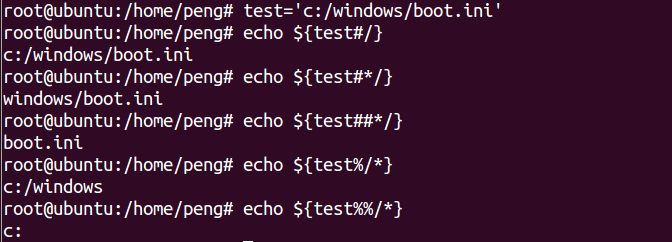

c) String removal

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# test='c:/windows/boot.ini'

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test#/}

c:/windows/boot.ini

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test#*/}

windows/boot.ini

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test##*/}

boot.ini

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test%/*}

c:/windows

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test%%/*}

c:

${variable_name#substring regular expression} removes the matching substring from the beginning of the string.

${variable_name%substring regular expression} removes the matching substring from the end of the string.

Note:

${test##*/},${test%/*} are the simplest ways to get the filename or directory address.

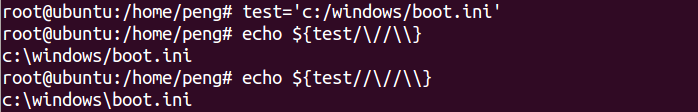

d) String replacement

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# test='c:/windows/boot.ini'

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test///}

c:windows/boot.ini

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo ${test////}

c:windowsboot.ini

${variable/replacement} indicates replacing the first occurrence with a single “/”, while “//” indicates replacing all occurrences. If “/” appears in the search, please escape it with “/”.

Note: The position of the string starts from 0, -1 indicates the last position of the string; when extracting a substring, it is left-closed and right-open, starting from the left position and ending at the right position, excluding the right position.

3. Creating and Executing Scripts

Shell scripts cannot be considered formal programming languages because they operate in the Linux shell, hence they are called shell scripts. In fact, shell scripts are a collection of commands. We generally record all operations in a document and then call the commands in the document, allowing a single operation to be completed. Generally, shell scripts are placed in the /usr/local/sbin directory.

1) Creating a Shell Script

In the Linux system, shell scripts (bash shell programs) are generally written in an editor (such as vi/vim) and consist of Unix/Linux commands, bash shell commands, program structure control sentences, and comments. It is recommended to use the vim editor.

2) Script Header (First Line)

A standard shell script’s first line indicates which interpreter will execute the contents of the script, typically in Linux bash programming:

#!/bin/bash

or

#!/bin/sh <== within 255 characters

The initial “#!” is called a magic number, and when executing a bash script, the kernel determines which program to use based on the interpreter following “#!”. Note: This line must be the first line at the top of each script; if it is not the first line, it will be treated as a comment line, as shown in the example below.

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# cat test1.sh

#!/bin/bash

echo "scajy start"

#!/bin/bash <== writing here is a comment

#!/bin/sh

echo "scajy en:"

Difference between sh and bash

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# ls -l /bin/sh

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 4 Sep 212015 /bin/sh -> bash

Tip: sh is a soft link to bash, so it is recommended to use the standard notation #!/bin/bash

Bash is the default shell for GNU/Linux, compatible with the Bourne shell (sh), and incorporates features from the Korn shell (Ksh) and C shell (csh). It complies with the IEEE POSIX P10003.2/ISO 9945.2 shell and tools standards.

In CentOS and Red Hat Linux, the default shell is bash, so when writing shell scripts, our script can also omit #!/bin/bash. However, if the current shell is not your default shell, such as tcsh, then you must write #!. Otherwise, the script file can only execute a collection of commands and cannot use shell built-in commands. It is recommended that readers develop the habit of always including the starting language identifier in any script, which will be mentioned again in the shell programming standards later. If the script does not specify an interpreter at the beginning, then the corresponding interpreter must be used to execute the script. For example: bash test.sh

3) Script Comments

In shell scripts, content following the (#) symbol indicates comments, used to explain the script. The comment section will not be executed; it is only for human reference. Comments can be on a single line or follow a command on the same line. When developing scripts, if there are no comments, others will find it difficult to understand what the script is doing, and over time, you may forget as well. Therefore, we should try to develop the habit of writing comments for our work (scripts, etc.), which not only benefits others but also helps ourselves. Otherwise, after writing a script, you may forget its purpose, and re-reading it will waste valuable time. This is also detrimental to teamwork.

4) Example

Create a file named first.sh and copy the following information into the file:

#cd usr/local/sbin

# vim first.sh

#! /bin/bash

##this is my first shell script

#written by 一口Linux 2021.5.3

date

echo "Hello world"

Shell scripts generally have a .sh suffix

Executing the script can be done in several ways:

#sh first.sh

#bash first.sh

#./first.sh

#./first.sh

If you get a permission denied error, you can:

#chmod +x first.sh

4. Using Environment Variables

1. Detailed Knowledge Points

-

In Linux Shell, variables are divided into system variables and user-defined variables.

-

System variables: HOME, PWD, SHELL, USER, etc. For example: echo $HOME, etc.

-

User-defined variables:

1) Define a variable: variable=value

2) Display all variables in the current shell: set

3) Unset a variable: unset variable

4) Declare a static variable: readonly variable, note: cannot unset

-

Rules for defining variables

1) Variable names can consist of letters, numbers, and underscores, but cannot start with a number.

2) There should be no spaces around the equals sign.

3) Variable names are generally conventionally written in uppercase.

-

Assign the return value of a command to a variable (key point)

1) A=`ls -la` Backticks, the command inside will return the result to variable A

2) A=$(ls -la) is equivalent to backticks

-

Basic syntax for setting environment variables:

export variable_name=variable_value (Function description: outputs shell variable as an environment variable)

source configuration file (Function description: makes modified configuration information take effect immediately)

echo $variable_name (Function description: queries the value of the environment variable)

2. Detailed Operations

Check the values of environment variables HOME and PATH:

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo $HOME

/root

root@ubuntu:/home/peng# echo $PATH

/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/home/peng/toolchain/gcc-4.6.4/bin:/home/peng/toolchain/arm-cortex_a8/bin

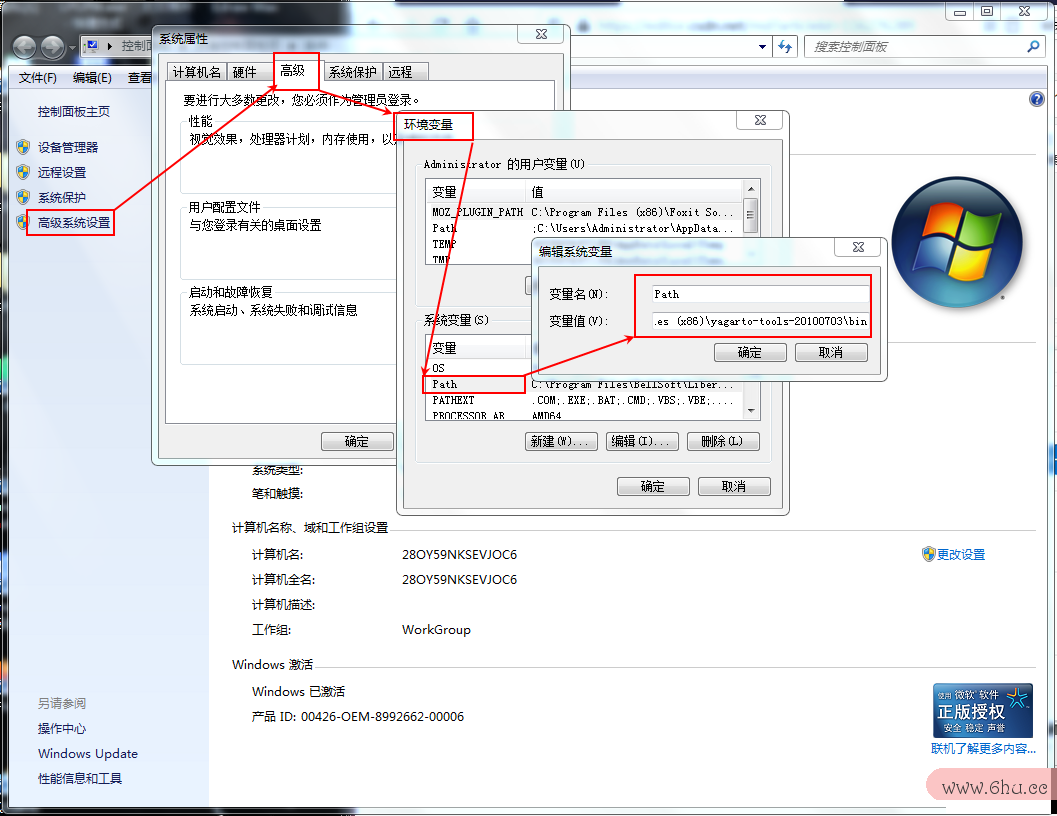

Check environment variables in the Windows system

Check all paths in the environment variable PATH, search for the public account: Architect Guide, reply: Architect to receive materials.

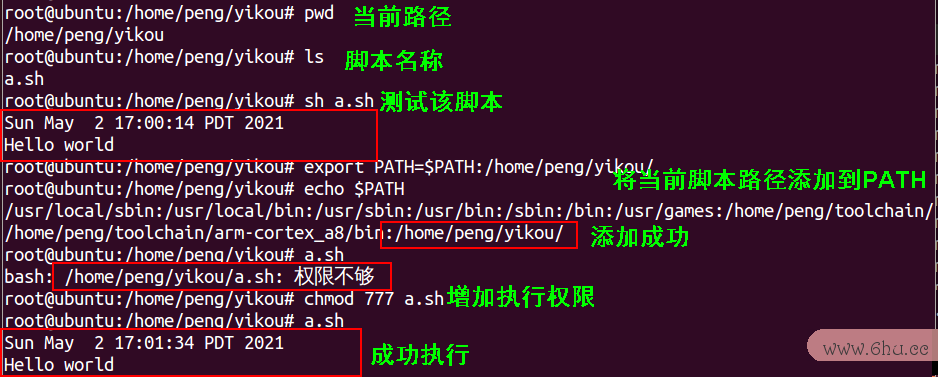

Examples of Script Path Configuration

Method 1: Modify the environment variable: add the specified “software installation” directory to PATH:

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# pwd

/home/peng/yikou

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# ls

a.sh

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# sh a.sh

Sun May 2 17:00:14 PDT 2021

Hello world

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# export PATH=$PATH:/home/peng/yikou/

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# echo $PATH

/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/home/peng/toolchain/gcc-4.6.4/bin:/home/peng/toolchain/arm-cortex_a8/bin:/home/peng/yikou/

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# a.sh

bash: /home/peng/yikou/a.sh: Permission denied

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# chmod 777 a.sh

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# a.sh

Sun May 2 17:01:34 PDT 2021

Hello world

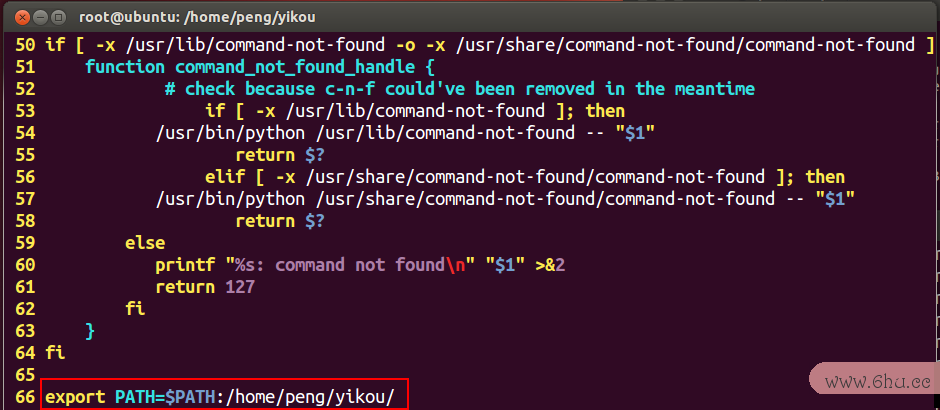

Method 2: Modify the environment variable configuration file to make the modified environment variable take effect permanently

vim /etc/bash.bashrc

source .bash.rc, makes the configuration file take effect again

Close the terminal, reopen it, and re-enter: a.sh can still be executed.

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/# a.sh

Sun May 2 17:10:00 PDT 2021

Hello world

5. Mathematical Operations

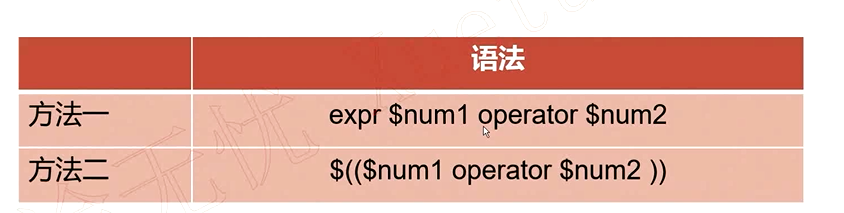

1. Detailed Knowledge Points

The syntax for using operators:

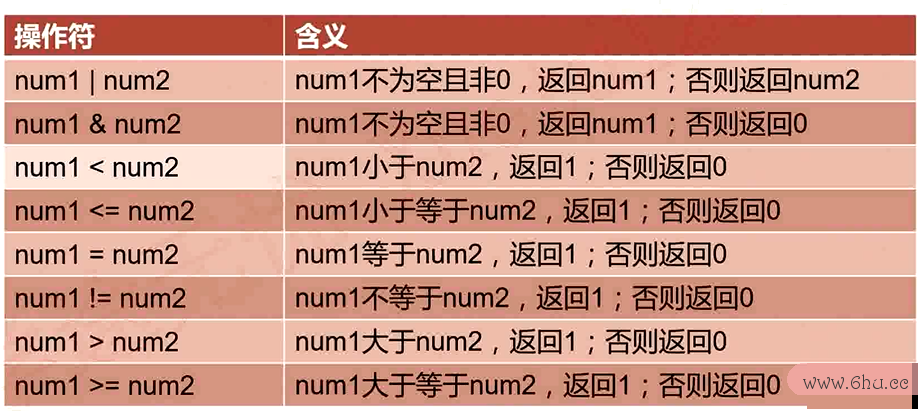

expr operator comparison table

2. Detailed Operations

-

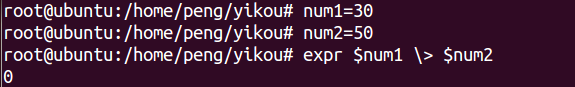

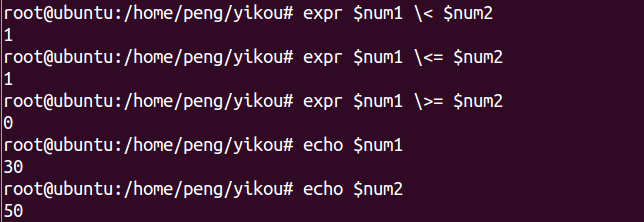

Comparing sizes can only be done for integers, spaces are required, and Linux reserved keywords need to be escaped

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# num1=30

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# num2=50

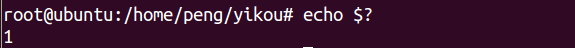

root@ubuntu:/home/peng/yikou# expr $num1 > $num2

Check if the previous command was executed successfully: Return 0 for success, others for failure

Return 0 for success, others for failure

-

Less than, less than or equal to, greater than or equal to

expr $num1 < $num2

expr $num1 <= $num2

expr $num1 >= $num2

-

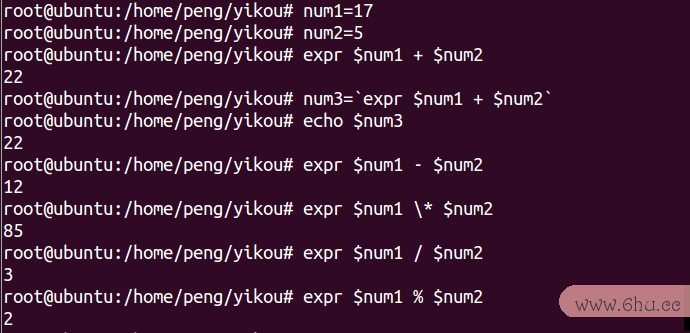

Operations: Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication, Division

# Addition

num1=17

num2=5

expr $num1 + $num2

# Subtraction

num3=`expr $num1 + $num2`

echo $num3

expr $num1 - $num2

# Multiplication

expr $num1 * $num2

expr $num1 / $num2

# Modulus

expr $num1 % $num2

Things to note:

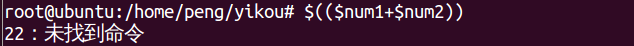

Things to note:

Two parentheses for calculations must be assigned; otherwise, an error will occur

6. Script and User Interaction

Operating Command Line Parameters

1. Reading Parameters

Bash shell uses positional parameter variables to store all parameters input from the command line, including the program name. Search for the public account: Architect Guide, reply: Architect to receive materials.

Among them, 0 indicates the program name, 0 indicates the program name, 1 indicates the first parameter, 2 indicates the second parameter, …, 2 indicates the second parameter, …, 2 indicates the second parameter, … 9 indicates the ninth parameter. If the number of parameters exceeds 9, the variable must be indicated as follows: 10, {10}, 10, {11}, …

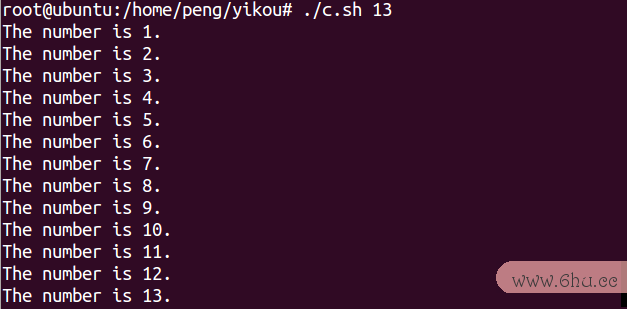

#!/bin/bash

# author:一口Linux

for((count = 1; count <= $1; count++))

do

echo The number is $count.

done

Execution result:

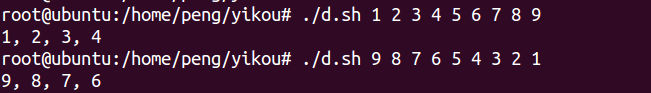

Modify the script as follows:

echo $1, $2, $3, $4

Execution result as follows:

2. Reading Program Name

The first thought is to use 0, but 0, but 0, but 0 gets the filename including ./ and path prefix information, as follows:

echo The command entered is: $0

# Work: ./

# Output: The command entered is: ./14.sh

If you want to get only the filename without ./, you can use the basename command:

name=`basename $0`

echo The command entered is: $name

# Work: ./

# Output: The command entered is: 14.sh

3. Special Variables

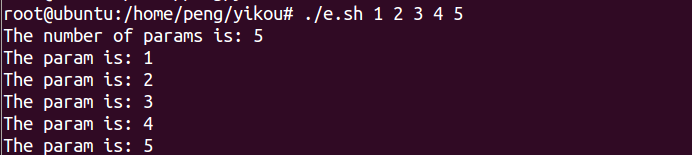

$# indicates the number of command line parameters:

#!/bin/bash

# author:一口Linux

params=$#

echo The number of params is: $params

for((i = 1; i <= params; i++))

do

echo The param is: $i

done

Execution result

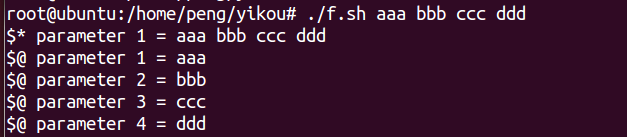

If you want to get all parameters, you can of course use # and loop through them one by one. You can also use the following two special variables:* treats all command line parameters as a whole, while $@ stores parameters separated by spaces individually, as follows:

#!/bin/bash

# author:一口Linux

count=1

for param in "$*"

do

echo "$* parameter $count = $param"

count=$[ $count + 1 ]

done

count=1

for param in "$@"

do

echo "$@ parameter $count = $param"

count=$[ $count + 1 ]

done

4. Basic Reading

The read command accepts input data from the keyboard or file descriptor and stores it in a specified variable.

Options:

-p: Specify the prompt when reading values;

-t: Specify the time (in seconds) to wait for input; if not entered within the specified time, it will stop waiting.

-n: Set the number of characters allowed for input

Parameters

variable: Specify the variable name to store the read value

Detailed Operations

-

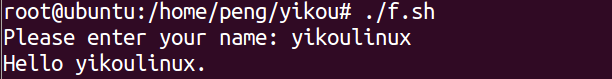

Example 1

#!/bin/bash

# author:一口Linux

# testing the read option

read -p "Please enter your name: " name

echo "Hello $name."

Execution result

-

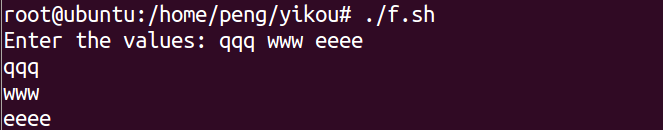

Example 2

In the read command, you can save the input data into multiple variables as needed. If the specified variables are fewer, the last variable will contain all remaining input, as shown below:

#!/bin/bash

# author:一口Linux

# testing the read option

read -p "Enter the values: " val1 val2 val3

echo "$val1"

echo "$val2"

echo "$val3"

Execution result:

-

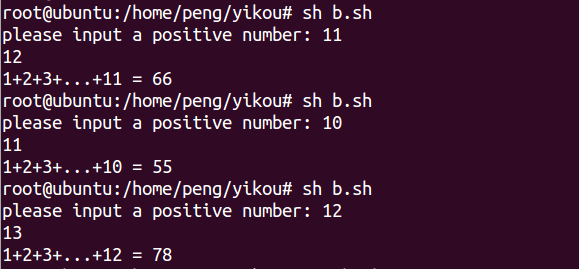

Comprehensive Example

Prompt the user to enter a positive integer num, then calculate the value of 1+2+3+…+num; it is necessary to check whether num is a positive integer, and if not, the program should prompt for input again.

Thought process:

-

expr can only calculate integers, directly use expr and an integer to get the value of $? to determine if it is an integer

-

Use expr $num1 > 0 to check if it is greater than 0

#!/bin/bash

# author:一口Linux

while true

do

read -p "please input a positive number: " num

# Check if the number is an integer

expr $num + 1 &> /dev/null

if [ $? -eq 0 ];then

# Check if this integer is greater than 0, return 1 if greater than 0

if [ `expr $num > 0` -eq 1 ];then

#echo "yes, positive number"

# $sum is not assigned, defaults to 0

for i in `seq 0 $num`

do

sum=`expr $sum + $i`

done

echo "1+2+3+...+$num = $sum"

# To execute the calculation, exit

exit

fi

fi

echo "error, input illegal"

continue

done

Test:

7. Relational Operators

Sometimes we need to compare the size relationship between two numbers, and this is when relational operators come into play. Relational operators only support numerical operations and do not support character operations.

1. Detailed Knowledge Points

Shell language supports the following relational operators:

-eq: Checks if two numbers are equal, returns true if equal.

-ne: Checks if two numbers are not equal, returns true if not equal.

-gt: Checks if the left number is greater than the right number, returns true if so.

-lt: Checks if the left number is less than the right number, returns true if so.

-ge: Checks if the left number is greater than or equal to the right number, returns true if so.

-le: Checks if the left number is less than or equal to the right number, returns true if so.

2. Detailed Operations

#!/bin/bash

# author:一口Linux

a=10

b=20

if [ $a -gt $b ]

then

echo "a greater than b"

else

echo "a not greater than b"

fi

Execution result! As follows:

8. String Operators

1. Detailed Knowledge Points

= Compares if two strings are equal

!= Compares if two strings are not equal

-z Checks if the length of the string is zero

-n Checks if the length of the string is not zero

$variable_name Checks if the variable is empty (null), returns True if it is, False if it is not

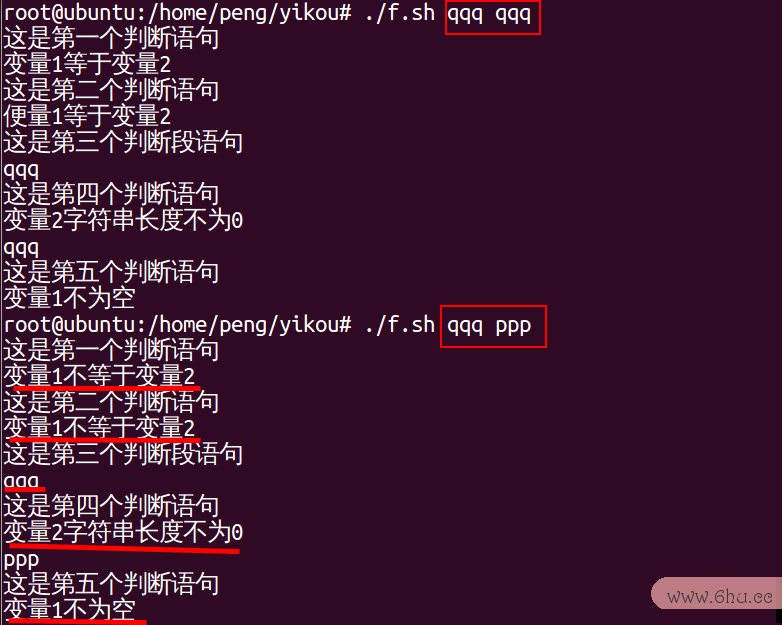

2. Detailed Operations

#!/bin/bash

# author:一口Linux

### This script is mainly used for string operators

if [ ! $1 ]

then

echo "The first parameter is empty"

echo "****************************************************************"

echo "****************************************************************"

echo "************** The format for executing the case is: sh $0 variable1 variable2 ***************"

echo "****************************************************************"

echo "****************************************************************"

break

else

if [ ! $2 ]

then

echo "The second parameter is empty"

echo "****************************************************************"

echo "****************************************************************"

echo "************** The format for executing the case is: sh $0 variable1 variable2 ***************"

echo "****************************************************************"

echo "****************************************************************"

break

else

###1. Check if two strings are equal;

if [ $1 = $2 ]

then

echo "This is the first judgment statement"

echo "variable1 equals variable2"

else

echo "This is the first judgment statement"

echo "variable1 does not equal variable2"

fi

###2. Check if two strings are not equal;

if [ $1 != $2 ]

then

echo "This is the second judgment statement"

echo "variable1 does not equal variable2"

else

echo "This is the second judgment statement"

echo "variable1 equals variable2"

fi

###3. Check if the length of the string is zero

if [ -z $1 ]

then

echo "This is the third judgment statement"

echo "The length of variable1 string is zero"

else

echo "This is the third judgment statement"

echo $1

fi

###4. Check if the length of the string is not zero

if [ -n $2 ]

then

echo "This is the fourth judgment statement"

echo "The length of variable2 string is not zero"

echo $2

else

echo "This is the fourth judgment statement"

echo "The length of variable2 string is zero"

fi

###5. Check if the string is not empty

if [ $1 ]

then

echo "This is the fifth judgment statement"

echo "variable1 is not empty"

else

echo "This is the fifth judgment statement"

echo "variable1 is empty"

fi

fi

fi

Test result:

9. Common Operations on Shell Files and Directories

-

Extracting the directory and filename from a path

Extract directory:

dirname $path

Extract filename:

basename $path

-

Batch renaming files with spaces

function processFilePathWithSpace() {

find $1 -name "* *" | while read line

do

newFile=`echo $line | sed 's/[ ][ ]*/_/g'`

mv "$line" $newFile

logInfo "mv $line$newFile $?"

done

}

-

Traversing file contents

cat /tmp/text.txt | while read line

do

echo $line

done

-

If the file does not exist, create the file

[ -f $logFile ] || touch $logFile

-

Recursively traverse directories

function getFile() {

for file in `ls $1`

do

element=$1"/"$file

if [ -d $element ]

then

getFile $element

else

echo $element

fi

done

}

-

Clear file contents

cat /dev/null > $filePath

-End-

Reading to this point indicates that you like the articles of this public account. Welcome to pin (star) this public account Linux Tech Enthusiast, so you can get the push first time~

In this public account Linux Tech Enthusiast, reply: Linux to receive 2T learning materials!

Recommended reading

1. ChatGPT Chinese version 4.0, everyone can use it, fast and stable!

2. Common Linux commands, a full 20,000 words, the most comprehensive summary on the internet

3. Linux Learning Guide (Collection Edition)

4. No need to translate the official ChatGPT and Claude and Midjourney, stable with after-sales