Will China’s chip industry inevitably fail? When John Smith, an expert from a Washington think tank, made this statement at a seminar, who could have predicted that three months later, Huawei would suddenly release the Mate60 Pro smartphone equipped with a 7-nanometer chip? In this seemingly unwinnable gamble, Chinese companies have managed to tear open a crack amidst heavy blockades.

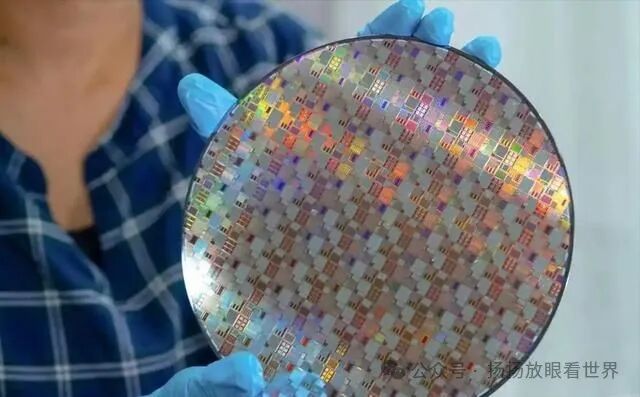

Watching the lights of the SMIC factory burning through the night, former TSMC engineer Li Mingxuan felt a surge of emotions. He had participated in the development of 3-nanometer chips but chose to return home to join a domestic equipment development team. “The leap from 14 nanometers to 7 nanometers, the Americans said would take ten years; we only took five years.” He caressed the model of the immersion lithography machine being tested in the lab, the glass cover reflecting the slogan on the wall, “Success does not have to be mine.” This speed of catching up that once drew global attention is backed by countless researchers who have stayed in the lab during three consecutive Spring Festivals.

When the first quarter financial report of 2025 was revealed, the entire industry held its breath. Cambricon’s 4230% revenue growth was like a shot of adrenaline, while the unexpected losses of Zhaoxin caused concern. This stark contrast reflects the microcosm of China’s chip industry—AI computing power and automotive electronics are surging forward, while consumer electronics are still struggling in the winter. Even more surprising is that North Huachuang’s etching equipment has entered Samsung’s production line. This company, once seen by ASML as a “follower,” is rewriting the rules of the game at a pace of adding 30 patents per month.

In the Suzhou Industrial Park, engineers at Yangtze Memory Technologies are debugging the world’s first fully autonomous 28-nanometer lithography production line. A special calendar hangs on the workshop wall, recording each day since the U.S. sanctions took effect. “If the Dutch won’t sell us EUV, we’ll make our own DUV,” said Chief Engineer Wang Jianguo, pointing to the equipment being assembled. “Multi-patterning technology does affect yield, but automotive chips do not require the extreme processes of 5 nanometers.” This statement reveals the survival wisdom of Chinese companies: when high-end processes are restricted, first capture the market share of mature processes.

The “double-edged sword” effect of policy support is gradually becoming apparent. The $47 billion investment from the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund Phase III has invigorated the industry, but news of certain local chip projects being abandoned has raised concerns. More dramatically, after ASML announced it would stop maintenance services for its equipment in China, Zhongwei Semiconductor received hundreds of consultation calls within three days. This “crisis breeds opportunity” narrative is being played out repeatedly in every niche.

Standing on the observation deck in Zhangjiang, Shanghai, one can see the research centers of twenty chip companies brightly lit. Behind these twinkling windows, some are debugging the low-temperature control systems for quantum chips, while others are optimizing the energy consumption ratio of integrated computing architectures. A report from the Development Research Center of the State Council shows that China’s chip self-sufficiency rate has climbed from 15% five years ago to 28%. This figure is supported by a daily production capacity of 1.24 billion chips. As we raise our glasses to celebrate Huawei’s breakthrough, should we also consider that establishing an absolute advantage in mature processes may be strategically more valuable than aggressively pursuing 3-nanometer technology?

Where will this life-and-death speed chip game lead? As American think tanks begin discussing the “backlash effect of sanctions,” and German car manufacturers start bulk purchasing flash memory chips from Yangtze Storage, perhaps the answer has already been written on the wall of the Suzhou laboratory: “It is not we who chose the battlefield; it is the battlefield that chose us.”

References: Annual Report on China’s Semiconductor Industry, Global Integrated Circuit Market Analysis, National Science and Technology Development Strategy White Paper