Viewing Architecture Lounge

We invite outstanding figures from architecture, engineering, art, and design fields both domestically and internationally to share their knowledge, experiences, and insights in their respective professions. While promoting healthy communication and development within the design industry, the aim is to inspire more friends to explore uncharted possibilities.

Featured Guest

In this edition of “Viewing Architecture Lounge”, we have invited former SOM China Director Silas Chiow to share his insights on urban planning and headquarters design, covering:

01 Stages of Headquarters Design

02 Focus Areas at Each Stage of Headquarters Design

03 The Future of Headquarters Design

04 Challenges of Height

05 Material Selection

06 Urban Planning

07 Uniformity Across Cities

08 Advice for Young Architects

01

Stages of Headquarters Design

So I am particularly concerned about how SOM views the various aspects of headquarters construction and development at each stage. Are there any unique characteristics at each stage? Moreover, with the surge of headquarters designs in China, what valuable advice can SOM provide us at this stage?

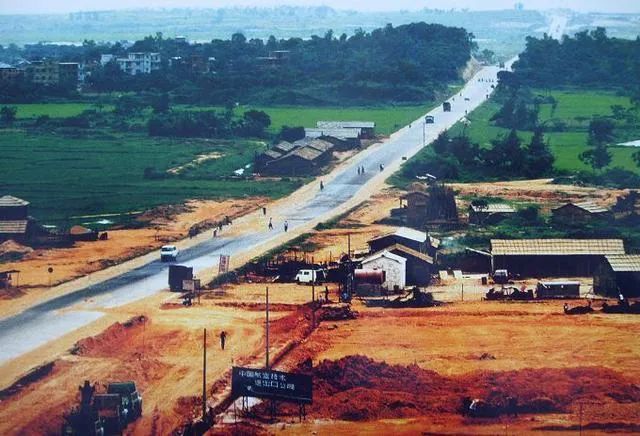

This is interesting. Because I’ve been involved in projects in China ever since the mid-1990s. Of course, at that time, the China market was totally different. I still remember very well when I first visited Shenzhen. More than 25 years later, Shenzhen is one of the most modern and advanced cities in China. Currently, Shenzhen is attracting all these technology companies to build their headquarters there.

▲Shenzhen in the 1990s (Image source: Internet)

▲Shenzhen in the 1990s (Image source: Internet) ▲Modern Shenzhen (Image source: Internet)

▲Modern Shenzhen (Image source: Internet)

I would like to point out the economic changes in China. In the 1990s, when I first came to China, China was the production and manufacturing center for the whole world. Today, China is exporting technology; innovations are being exported from China rather than just manufacturing things and products for the rest of the world.

So if we are talking about “the early stage”, this was when companies were building small functional headquarters within their manufacturing production site. Today, these technology companies, they are looking for prime real estate sites. They want to build buildings that become symbols of their company or for their brand.

02

Focus Areas at Each Stage of Headquarters Design

SOM has completed many headquarters buildings in the United States since its establishment in 1936, including Citibank, etc. What were the focus areas of headquarters design at that time? Additionally, has SOM’s focus on headquarters design changed over the long history? Are there any stages in this process? What are the characteristics of each stage?

I think this is what makes SOM interesting. Although SOM’s projects are spread all over the world, we do not impose a fixed design methodology or idea on projects in different regions. SOM’s design philosophy is to start from the local context, understanding the project’s location, the users, the owners, and the local culture. After conducting thorough research and understanding, we begin the design.

Since SOM was founded in 1936, the biggest change has occurred in building technology. Many of our projects, even those built over fifty years ago, still maintain high flexibility to adapt to new technologies required for modern headquarters office functions.

In addition to addressing technological changes, SOM always first understands the needs of the people who will work in the headquarters office building before starting the design. After organizing these needs, you can derive the appropriate spatial relationships suitable for the entire building. Some headquarters buildings are 95% used for internal operations, while others are used as R&D centers, etc. Different functions determine the different forms of the building, which is very important. How different departments should be distributed and their adjacency relationships are all considerations we take into account when thinking about the building’s layout.

For General Motors, they wanted to isolate their R&D center from the outside world, not wanting to leak their design secrets to visitors or other company employees.

▲Inside GM’s Office Building ©SOM

▲Inside GM’s Office Building ©SOM

But at KIA, they wanted “transparency”. They want visitors and employees to all see the kind of design their designers are coming out with. So when you look at these two buildings’ interiors, it’s very clear that KIA is very transparent in both interiors and in architecture design. And in the meantime, the design for the GM headquarters, the design center becomes very secretive, “kind of undercover”, people don’t know where it is. So there is this customized approach to understanding the “headquarters culture/value”. When you understand that, then how we represent to the world will be obvious from the architectural design.

However, for Kia, they emphasize transparency. They want visitors and employees to be aware of the latest designs from their R&D team. Therefore, when you compare the interiors of these two buildings, it is clear that Kia embodies a transparent corporate characteristic in its design, while General Motors’ design center appears more secretive, making it hard for people to discern its location. Understanding corporate culture/values and customizing the design based on that principle enables SOM to effectively present our designs to the outside world.

I want to share another project, which is the Lever House that Mr. Qiu just mentioned, and it is one of my favorite buildings among many projects that SOM has completed. I think this building is now about 70 years old. After its completion, SOM was invited to renovate the building, updating its technology and materials. However, since Lever House was designated as a New York City landmark in the 1980s, we could not change its exterior appearance. Therefore, in terms of exterior design, the glass color, window frames, and other design details have not changed; we only updated the facade materials.

▲Lever House ©SOM

▲Lever House ©SOMReturning to this landmark building, it is a simple, open office slab tower that rises in the east-west direction, perpendicular to Park Avenue, the main road in Manhattan, New York. People often wonder why the building is positioned perpendicular to the main street. The primary reason is that the designer placed the narrower side perpendicular to zoning regulations, allowing the slab to be closer to the street. You cannot completely enclose the street; if the facade is too wide facing Park Avenue, it would need to be set back. Additionally, this design allows the workers in the building to have a better view of Park Avenue, which is also visible to those driving along it. This feature is crucial in reflecting the corporate culture within Lever House.

Another design focus is how the building interacts with the ground and relates to the city. The SOM design team intentionally raised the ground floor to create a plaza for pedestrians. In rainy or snowy weather, people can wait for taxis or buses under the covered area of the building. This public plaza connects to the city and its passersby, creating a welcoming gesture for visitors and employees entering the building.

03

The Future of Headquarters Design

I would like to take this opportunity to ask Mr. Zhou to reveal SOM’s new visions for the future of headquarters design.

This is a very good question. SOM’s designers and the entire team attach great importance to innovation. Technology has increasingly integrated into our daily lives. Twenty years ago, we didn’t have smartphones. But today, we can communicate through phones, control home appliances, and even monitor our children at home. The role of phones has vastly exceeded simple communication.

In the office, it’s similar. Technology is deeply integrated into our daily lives, which we cannot ignore in office or headquarters design. Therefore, I believe that innovations in technology and artificial intelligence will enhance operational efficiency and communication within teams. This is a critical and essential aspect of designing headquarters buildings today.

04

Challenges of Height

You just mentioned that our designs in the future may need to better align with technological advancements. In fact, I have also noticed that throughout the process of building architecture, we have mastered more scientific and technological methods, using them to challenge height and overcome gravity. I think SOM has been a pioneer in this process. I can cite examples such as Chicago’s tallest building—the Sears Tower, New York’s current tallest building—the Freedom Tower, and the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

▲Sears Tower ©SOM

▲Freedom Tower ©SOM

Shenzhen also has the most skyscrapers over 200 meters in China. I am particularly concerned about how SOM, as an important expert in skyscraper and high-rise design in this era, can challenge this content or what suggestions it can provide for China’s design in the future?

This is a very interesting topic. Even within SOM, architects, structural engineers, and urban planners often debate whether super-tall buildings are suitable for the scale of cities. At a certain height, the efficiency of the building and the materials required to reach that height become contentious issues. Whether height is the only solution is a question we continuously grapple with.

Clients often approach SOM wanting to design super-tall buildings, aiming for landmark projects. However, there are many ways to create landmark buildings, some of which can be shorter. We recently completed a project for the Shenzhen Rural Bank, which is only 150 meters tall. Yet, even this shorter building integrates numerous innovative ideas in design, technology, and structure.

▲Shenzhen Rural Bank Building ©SOM

I believe there will continue to be a market for tall buildings worldwide, but there is also increasing awareness regarding material efficiency and sustainable design in tall buildings. As a result, the number of tall buildings will gradually decrease. The current trend in China, where the government is limiting the construction of tall buildings, is compelling architects, engineers, and owners to approach tall building design more thoughtfully. I believe a 200m tall building can serve as a landmark in a city; it all depends on how you plan and design it. I anticipate that 200m buildings will become increasingly common in the future, as they are sufficiently tall to be landmarks while maintaining user efficiency for vertical transportation. You don’t want to spend all day riding elevators in super tall buildings. Once you reach the top of the tallest building in the world, you may not want to come down, which means all activities would have to occur at the top.

I believe future architecture should pursue functionality and added value, as well as provide users with a better quality of life and environment.

05

Material Selection

I have another particularly interesting question, perhaps a joke, but I would like to take this opportunity to confirm with Mr. Zhou. I have architect friends who have mentioned a story about SOM’s design of headquarters buildings or super-tall buildings: they say SOM’s designers will suggest clients choose a particular stone because it is very suitable for them, and I recommend that you buy the quarry to ensure the quality and characteristics of the building. After you use it up, we can sell the quarry again. I want to take this opportunity to confirm with you if this is true?

It’s possible that someone at SOM said this. However, it doesn’t align with our principles. I would more likely think it was meant as an “ironic” statement. If there is a stone quarry near a project site, we should indeed consider using that local stone. This is not only due to the relationship between the quarry and the project location but also for carbon neutrality. Shipping stones from Italy to China, which is quite common, results in significant carbon emissions, which contradicts modern designers’ values.

Therefore, I would prefer to believe that a responsible designer or architect, whether at SOM or elsewhere, would prioritize using materials sourced from the vicinity of the project site, ensuring a connection to the location. Continuously importing beautiful stones from Italy to a distant project site is not a sustainable approach for the future of architecture.

06

Urban Planning

I have seen SOM’s footprint in many architectural designs in China. In fact, I have noticed for a long time that SOM has achieved remarkable success not only in super-tall buildings but also in many headquarters designs. They have also participated in a large number of urban design and planning projects worldwide. For example, the Canary Wharf in the UK, which seems to have been under construction and planning since the 1980s; I have also seen SOM’s early involvement in the urban design of the Futian Central District in Shenzhen; I recently saw SOM provide design solutions for the Xiong’an New Area in China, which is also a fantastic implementation plan.

▲Canary Wharf Overall Planning ©SOM

I would also like to take this opportunity to ask what principles SOM adheres to in urban planning and design, and what good suggestions it can provide for the current urban development and planning design in China?

Since the 1980s, China has undergone urbanization, and it has reached 60%, possibly even 65% now. This speed of development is astonishing. Urbanization entails both regenerating existing cities and expanding cities to accommodate the growing population.

When I first came to Shanghai in 1994, I was told there were about 10 million residents, along with around 2 million migrants. Today, the resident population has exceeded 20 million, and the number of migrants might be around 5 million, resulting in a total of approximately 25 million people, which is more than double the figure from 25 years ago. This growth rate is equally astonishing.

Due to the rapid urbanization in China, urban renewal and expansion have become increasingly important in urban planning and design. The Chinese government and planning departments are very astute, spending considerable time contemplating how to build cities. It’s well known that Chinese officials learn quickly. I recall in the late 1990s and early 2000s, their approach involved inviting foreign architects and planners to propose various concepts, referred to as “idea or scheme collections”. They would then integrate these ideas with local design institutes to create the final plan. At that time, there was a belief that foreigners did not fully understand how Chinese people live, which is likely true. This was the situation before 2000, but by 2010, just a decade later, China had made significant progress and tremendous growth.

Many officials and planning department personnel have traveled abroad, gaining insights into how cities function and learning to collaborate directly with architects and planners. SOM has been involved in many of these projects, and we were among the first firms to advocate for the development of design guidelines for buildings, allowing us to influence their appearance and functionality. Ultimately, a plan is two-dimensional, while a city is three-dimensional. Therefore, a visually appealing plan alone is insufficient. The building’s form shapes the street space and the areas between buildings; this aspect of design and planning is paramount, and the SOM team recognizes its significance.

I have been instrumental in developing urban design services with my then-design partner Philip Enquist since around 2004 and 2005, focusing on urban design in China. Over two years, Philip and I repeatedly visited 7 or 8 cities across China—Wuhan, Tianjin, Chengdu, Chongqing, Guangzhou, Hangzhou, Shenzhen, etc. We engaged with planning bureaus and district officials, which allowed us to undertake numerous projects in these cities, particularly in Wuhan and Tianjin. These opportunities helped us establish best practices and methodologies for effective collaboration with the Chinese government and planning bureaus. Our experiences ultimately contributed to our success in the Xiong’an project, as after 13 to 14 years of working in China, we gained valuable insights into what works best for Chinese cities, making Xiong’an a significant opportunity.

07

Uniformity Across Cities

I am also particularly concerned about the issue of how China has achieved a 55% urbanization level in such a short time. As a citizen living in China, I have observed significant changes around me. However, I also notice that due to the rapid pace of urbanization, many cities have experienced a lot of copying, resulting in uniformity across cities. Whether it is the northeastern cities or those in Hainan, the architectural forms and urban spaces are very similar, making it difficult to distinguish which region a city belongs to.

I believe this involves some issues in urban planning and design, as well as urban growth and development. I feel that our cities seem to have lost some diversity and uniqueness during this rapid urbanization process. I wonder what good suggestions SOM can provide for urban design and planning in China, or what strategies SOM has in this regard?

This is also a very good question. In urban design and planning projects, our design principles remain consistent: responding to the local climate, culture, and engaging with local residents.

Urban planning for Beijing and Shenzhen must differ. The climates of these two cities vary; their cultures, while both Chinese, have distinctions; and the residents of each community bring different perspectives. All these factors influence the planning process. A successful plan cannot simply be transplanted from one location to another.

Actually, we really enjoyed many of these opportunities that we had in China. When working in different cities—understanding the city’s history, understanding the geography before we get into a plan, that process itself, probably is the most enjoyable part of the design process. I, with Philip Enquist, we’ve taken many site visits. It’s so enjoyable when we first discovered the site, discovered what was there and what are the surroundings, how people lived. We would always look at all the neighborhoods close by the site. And, in the end, it gives us “the” inspirations for our project.

SOM has always greatly enjoyed these project opportunities in China. Each project team visits different cities to understand the local history and geography. This research process is often the most enjoyable part of the design process. I have conducted numerous site visits with Philip Enquist, where we observed the surroundings, the lifestyles of local residents, and nearby neighborhoods, all of which ultimately inspire our design.

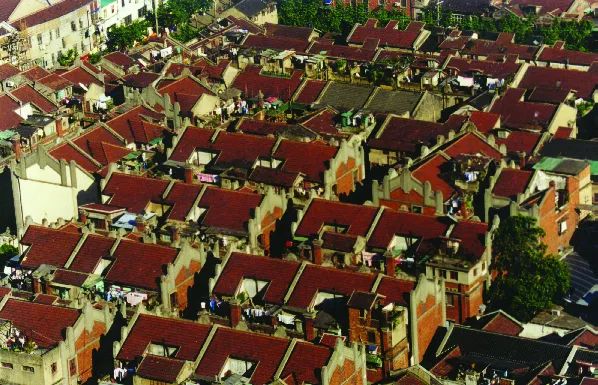

I do want to take the opportunity to talk about a true story. We were invited to design and plan the Taipingqiao Area in Shanghai, which included the now famous “Xintiandi”. This was back in 1996; at the time, we had to work with the district and with the state-owned developers. Originally, the directive was to just tear down all these Shikumen blocks. To make way to build new buildings as a mixed-use development complex: office, residential, and retail. I think it was in August of 1996. Back then, those lane houses or Shikumen, they were like these 13-foot wide per unit row houses. Originally, were designed for one family use. But back then in 1996, sometimes you see 2 or 3 families or even more in “one” of these lane houses. Even different families could be living on one floor, just separated by curtains between for the families’ privacy. And then we watched kids playing Ping Pong in this very narrow lane. We watched old ladies washing their vegetables to prepare for their lunch that they cooked in their lane houses courtyards. All these things actually really inspired us and informed us – the designers and planners, that we need to keep that “memory from that lane houses”. So we convinced the district to maintain, or preserve these two blocks that become known as Xintiandi today.

I would like to share a true story. In 1996, SOM was invited to design the Taipingqiao area in Shanghai, which includes the now-famous Xintiandi. At that time, we collaborated with the district and state-owned developers. The initial directive was to demolish all the Shikumen blocks to make way for a mixed-use development complex that combined office, residential, and retail functions. I remember it was August 1996. Those Shikumen lane houses were about 13 feet wide, originally designed for single-family use. By 1996, it was common to see 2 or 3 families living in one unit, often separated by curtains for privacy. We observed children playing ping pong in the narrow lanes and elderly women washing vegetables in their courtyards to prepare lunch. These experiences inspired us as designers and planners to preserve the memory of these lane houses, and we successfully convinced the district to maintain the two blocks, which are now known as Xintiandi.

08

Advice for Young Architects

Today, taking this precious opportunity has truly showcased a very authentic SOM. Here, we see SOM’s work, their ideas, their beliefs, and so on, which greatly benefits Chinese architects.

As a final note, I would like to take this opportunity to ask Mr. Zhou to offer some advice to the many newly established design firms and young architects in China.

I really appreciate the quote from Steve Jobs during a graduation speech. It’s a simple yet profound message: “Stay foolish and stay hungry.”

It is crucial to maintain a sense of “foolishness”. This openness allows for new ways of thinking. Meanwhile, a hunger for knowledge compels you to embrace this foolishness in your learning. This is particularly important for young architects, but it also applies to engineers, researchers, laboratory technicians, and others.

I believe that we are living in a remarkable period in history, despite the various crises we face, including the pandemic and economic and political tensions. This is an exciting time where technology is becoming increasingly pervasive, and people are pushing boundaries. In the next 20 years, these technologies will fundamentally alter how we work, live, and conduct various activities. Everything is set to change! The pandemic will also drive new ideas and technological applications in everyday life. I am optimistic about the future, as it will provide young people with opportunities to create and explore the unknown. This is my advice to the youth today.

* Some images in this article are sourced from the internet and will be removed upon request.

-end-