Abstract

The rapid development of generative artificial intelligence is currently sparking a new wave of technological revolution globally, making AI an indispensable digital infrastructure in people’s daily lives and social operations. In this context, AI achieves organic embedding of platform labor through two parallel logics of regulation and control, and based on intelligent operational mechanisms including panoramic surveillance, algorithmic taming, excessive competition, and automatic regulation, it realizes fine control over the labor process, labor rhythm, labor consciousness, and the automation of labor exploitation. At the same time, AI-driven platform labor exacerbates the risks faced by platform workers in terms of employment dependency, physical and mental health, and labor protection. There is an urgent need to focus on self-regulation by platforms, government supervision, institutional construction, and technological co-governance to actively regulate the application of AI in platform labor, prudently govern the social risks arising from related negative effects, and promote the achievement of the goal of “AI for good”.

Keywords

Artificial Intelligence; Platform Labor; Platform Economy; Labor Control; Algorithmic Governance

Author Introduction

Li Tao, Dean of the Institute of Social Management at Beijing Normal University, Professor at the School of Journalism and Communication, and PhD supervisor; Chai Yunchao (corresponding author), PhD student at the School of Journalism and Communication, Beijing Normal University.

Source

Journal of the Party School of the Central Committee of the C.P.C. (Chinese Academy of Governance), 2025, Issue 1, references omitted.Introduction

The decision made by the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China clearly states the need to “promote the innovative development of the platform economy and improve the regular regulatory system for the platform economy” and “establish a safety regulatory system for artificial intelligence”. Currently, artificial intelligence has become an indispensable digital infrastructure for maintaining daily life and social operations, playing a foundational role in restructuring and re-logic of various actors or production factors such as people, goods, capital, and information in the digital age. Especially since the release of ChatGPT by OpenAI in November 2022, generative artificial intelligence has gradually become the latest trend in global AI development. The exponentially growing algorithmic models not only lead the technological frontier of the new generation of general artificial intelligence but also profoundly shape many social fields, including the platform economy. Among them, platform companies represented by food delivery, express delivery, and ride-hailing platforms fully utilize the technical efficiency of AI systems and embed them throughout the labor process, further enhancing production efficiency while absorbing a large number of workers. The latest results from the ninth national survey of the workforce show that the number of new employment form workers, including ride-hailing drivers, couriers, and food delivery personnel, has reached 84 million, accounting for about one-fifth of the total workforce in the country.

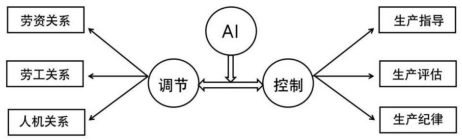

The accelerated expansion of platform labor scale is inseparable from strong technical support, and the comprehensive embedding of AI technology endows the operational mechanism of platform labor with stronger intelligent attributes. However, as Austrian scholar Mark Coeckelbergh stated, “AI has not only a technical logic but also a social logic, especially the logic of producing surplus value”. The embedding of AI in platform labor is not only the result of technical logic but also a process of mutual construction and integration of technical logic and platform political economic logic. How does AI embed itself in platform production and profoundly influence platform labor? How does AI-driven platform labor operate under the dual logic of technology and capital, forming a stable and controllable labor order? In the face of the potential social risks that may arise from the embedding of AI in platform labor, how should we conduct prudent governance? This series of questions constitutes the current focus of research in the fields of platform economy and digital governance.1. The Embedding of AI in Platform LaborArtificial intelligence, as an integrated system of machine learning algorithms and mathematical models, does not influence platform labor as an external force but is closely embedded in the political economic structure of the platform, thereby shaping the production process and operational mechanism of platform labor. The concept of “embedding” was originally proposed by Hungarian scholar Karl Polanyi, who believed that the motives and conditions of production activities, which have long been studied in isolation, are embedded in the overall organization of society, and thus must be examined from the perspective of social embedding to understand the complexity of economic issues. American scholar Mark Granovetter further developed this concept, dividing the embedding process of individuals into two forms: “relational embedding” and “structural embedding”. The former refers to the embedding of people’s intentions in the social relational system they are in, while the latter emphasizes the profound impact of the network structure of individual embedding on themselves. Unlike the individual embedding process focused on by economic sociology, AI, as a non-human technical system, completes the substantial embedding of platform labor by exercising functions such as authorization, permission, provision, encouragement, suggestion, influence, and prevention within the heterogeneous platform network connected by different actors. Overall, this embedding process mainly includes two parallel action logics: first, as an operational medium, it embeds a series of production relations involved in platform labor and exerts regulatory effects; second, as an information hub, it embeds the production process centered on platform labor and exerts control (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The Logic of AI Embedding in Platform Labor

(1) Regulatory Logic: Embedding Production Relations as an Operational Medium

The strong rise of generative artificial intelligence has pushed the entire development path of AI from specialized intelligence to general intelligence, gradually moving out of the traditional industrial production space and widely embedding and profoundly influencing various social life fields. At the macro level, AI reconstructs the underlying logic of operation for various social systems by building interactive networks based on big data analysis and algorithmic decision-making, thereby creating diversified new social relations; at the micro level, AI fully penetrates various application scenarios in people’s daily lives, and individuals’ lifestyles and social activities are largely influenced by the covert yet powerful regulation of AI systems. From the perspective of media studies, in the current prevalent “intelligent” lifestyle, AI has become what American scholar John Durham Peters refers to as “logistical media”. This type of media refers to those technologies, devices, or structures that can “sort various basic conditions and basic units… have the function of organizing and calibrating directions, can place people and things on a grid, coordinate relationships, and issue commands. It integrates personnel and connects everything”. Specifically, in platform labor, AI, as an operational medium, deeply intervenes in the production relations constructed around platform labor, ensuring the effective implementation of platform rules and the stability and sustainability of platform labor order.

AI carries various relationships in platform labor and exerts regulatory effects, mainly including three aspects: first, labor-capital relations, which refer to the interaction between platform workers and platform management; second, labor relations, which refer to the interaction among platform workers; third, human-machine relations, which refer to the interaction between workers and technical systems in platform labor. In terms of labor-capital relations, AI, as an integrated algorithm system owned by platform enterprises, can automatically execute platform rules in labor scenarios by exercising technical commands, thereby transforming part of the labor-capital relationship into the relationship between workers and technical systems. This not only strengthens the management and discourse power of the capital side over platform labor but also reduces the risk of direct conflicts between platform workers and management. In terms of labor relations, the digital platforms driven by AI construct horizontal competition among platform workers through radial algorithms. This competitive relationship is mainly reflected in the platform system’s mechanisms such as “grabbing orders”, “ranking”, and “competition”, and the process of regulating workers’ competitive relationships is also a process of strengthening vertical management of platform workers through incentives, effectively avoiding large-scale rights protection alliances or internal unions among workers. In terms of human-machine relations, workers in platform labor need the support of various hardware and software, including smartphones, map navigation, voice assistants, and platform systems, to successfully complete their labor tasks. The algorithms and program codes behind AI dominate the entire labor process and continuously regulate the interactive cooperation relationship between workers and machine systems, accelerating the flexible integration of human-machine relations.

(2) Control Logic: Embedding the Production Process as an Information Hub

AI supports a series of complex technical processes such as the collection, filtering, and calculation of massive data streams and information flows generated in real-time by platform systems. Based on the classification aggregation of all data and algorithmic decision-making, AI, as an information hub, controls the entire production process of the platform. American scholar Richards Edwards believes that the control exerted by enterprise managers over the production process mainly includes three dimensions: 1. Guidance dimension, which refers to the mechanisms or methods for managing work tasks, including specifying which tasks need to be completed, the order of task completion, the required precision or accuracy, and the time limits for completing tasks; 2. Evaluation dimension, which refers to the process of supervising and evaluating performance, including correcting errors in production, assessing individual workers’ performance, and identifying individuals or groups that have not fulfilled their work responsibilities; 3. Discipline dimension, which refers to the rewards or punishments for workers, aimed at promoting cooperation and ensuring that workers comply with management’s instructions regarding the production process. With the transformation of production methods and changes in labor forms, the means of control that enterprise managers exert over the entire production process are constantly being updated and increasingly exhibit highly technical characteristics. Currently, the control of platform production under the embedding of AI is shifting from visible physical machines and computer devices to invisible algorithms, models, and data, but the inherent logic shares commonalities with traditional production control methods. The three dimensions of guidance, evaluation, and discipline are deeply embedded in the platform production process through the reshaping of AI systems, hiding the control structure behind “neutral” technical devices.

From the guidance dimension, AI-driven platforms order and decompose labor task orders through algorithms while formulating standardized task processes. Workers must perform labor operations according to established steps and provide real-time feedback on progress to the intelligent control system. In food delivery labor, the algorithm system remotely regulates the order volume and delivery process of riders through large-scale real-time information interaction. Riders can only complete orders by following the system’s information prompts, route planning, and time limits. From the evaluation dimension, AI evaluates workers’ labor performance by widely collecting data on their labor processes and customer feedback, and it compares individual performance with average levels to allocate labor and control compensation. Ride-hailing platforms utilize service distribution systems and online duration to assess drivers’ labor volume, and the evaluation results serve as the basis for system order distribution, effectively increasing drivers’ platform stickiness and labor time while implementing the value orientation of “more work, more pay” in platform labor. From the discipline dimension, AI provides an automated discipline enforcement mechanism for platform managers through data extraction and algorithm training, with the core being the rewards and punishments for workers, aimed at internalizing technical control, platform rules, and production order among workers. For example, the reward and punishment rules based on delivery punctuality, customer satisfaction, and attendance data directly affect riders’ income. It is worth noting that all three dimensions involve time control, as food delivery, ride-hailing, and other platform labor mostly occur in circulation links. For the capital side, “the closer the circulation time is to zero, the greater the function of capital, the higher the production efficiency of capital, and the greater its self-reproduction”.

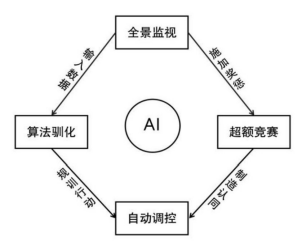

2. The Intelligent Operational Mechanism of Platform LaborThe dual embedding of AI not only profoundly influences the production processes and labor methods of platforms but also further reshapes the operational mechanisms of platform labor, endowing it with stronger intelligent attributes. Specifically, AI-driven digital platforms achieve intelligent control over the labor process, labor rhythm, labor consciousness, and the automation of labor exploitation through the close integration of panoramic surveillance, algorithmic taming, excessive competition, and automatic regulation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 The Intelligent Operational Mechanism of Platform Labor

(1) Panoramic Surveillance: Creating Visibility in the Labor Process

Since the Industrial Revolution, surveillance has become an indispensable control link in the capitalist mode of production, as a way to exert power over specific groups. Marx pointed out in his study of the management system of capitalist factories that, “Just as the army needs officers and sergeants, a large number of workers working under the same capital command also need industrial officers (managers) and sergeants (foremen) to command in the name of capital during the labor process. Supervision work is fixed as their full-time job.” When factories aim to continuously improve production efficiency and accelerate capital appreciation, workers, as variable capital, must inevitably be under strict surveillance, thus forming management’s control over the entire labor process. Regarding the mechanism of surveillance, Michel Foucault’s concept of “panopticism” based on the idea of the “circular prison” best explains the internal logic of surveillance and is the ideal form of surveillance, as it allows the monitored subjects to always be in a “conscious and continuous visible state, ensuring that power operates automatically”. Specifically in the production field, capital attempts to maintain the visibility of the labor process through surveillance, placing workers in a tense environment where they can be watched and punished at any time, thus preventing them from slacking off and providing references for timely labor regulation.

Traditional labor surveillance mainly relies on human power and fixed physical equipment, making it difficult to adapt to the decentralized, mobile, flexible, and de-spatialized nature of platform labor. It was not until the organic embedding of AI technology that platform surveillance gained the technical affordance to achieve “panoptic visibility”. In the digital age, AI-driven platform surveillance focuses more on the collection, storage, processing, evaluation, and use of information during the labor process, constructing asymmetric power relations of control, domination, and punishment. For example, in food delivery platforms, riders, as workers, must keep their app systems online through smartphones at all times to receive labor instructions from the backend and provide real-time feedback on their labor progress, making their labor fully visible throughout the process. From order waiting, order grabbing, order dispatching, order accepting, to the rider’s real-time location, route planning, arrival time, delivery time, user evaluations, and other labor links and dynamics are under the surveillance of the platform’s intelligent system, achieving complete tracking and recording of the labor process.

It is worth noting that the visibility of the platform labor process is not only directed at the platform enterprises themselves but also opens part of the permissions to the customer interface. With the support of intelligent systems, mobile terminals, and other hardware and software, both the platform and customers participate in the full surveillance of the food delivery labor process. As a centralized digital system, the platform relies on the nesting and collaboration of multiple AI technologies such as intelligent sensing, intelligent navigation, intelligent computing, and intelligent assistants, but its core remains to maximize the visibility of all “bodies, individuals, and things” associated with the platform labor process, as well as the labor discipline and regulation imposed based on visibility. Ivan Manokha believes that the history of labor surveillance is a series of attempts and innovations by managers to achieve a panoramic view of the workplace, but it was not until the rise of digital and intelligent surveillance technologies that this goal was realized, and panoramic surveillance constitutes the foundation of platform labor operations.

(2) Algorithmic Taming: Mastering Control Over Labor Rhythm

The rise of AI is leading people into an increasingly technological, computational, and data-driven society, where all production and life fields are inevitably under surveillance, “as data is captured and recorded, subsequently classified, stored, and processed by digital systems… These data will be used for commercial purposes, training machine learning AI systems, predicting and controlling human behavior”. Therefore, algorithms constitute the key to AI. As a composite control structure based on mathematical logic and machine learning methods, algorithms achieve specific purposes under given conditions through instructions and have deeply integrated into platform labor. The technical team of Meituan platform once introduced the operation process of its intelligent algorithm system at the ArchSummit Global Architect Summit: from the moment a customer places an order, the system immediately decides the dispatch target based on the rider’s route suitability, location, and direction. Orders are usually distributed in the form of 3 or 5 linked orders, including two task nodes of picking up and delivering food. Assuming a rider takes on 5 orders, that is, 10 task nodes, the system can quickly complete real-time matching of tens of thousands of orders and users among 110,000 possible route plans and calculate the optimal delivery scheme.

Edwards believes that enterprise managers will conduct necessary technical control in the workplace, often by designing systems and planning workflows to minimize the conversion of labor into work and improve purely physical production efficiency. In platform labor represented by food delivery, algorithms serve as a form of intelligent technical control, achieving control over labor rhythm through the gradual decomposition of task processes, precise calculation of task progress, and intelligent planning of task paths. Among them, various decomposed micro-tasks will indicate the required labor time, and the algorithm system conducts real-time fine measurements, with workers only able to receive corresponding compensation if they complete tasks within the specified time. Meanwhile, the algorithm-driven rating system will also impose “intelligent” rewards and punishments on platform workers based on the number of orders completed, the proportion of accepted or rejected orders, availability in designated areas, and customer evaluations. Technically, this greatly compresses time costs and human waste in platform production but also overlooks the reality of workers as autonomous individuals in complex labor environments. The strict control of labor rhythm by algorithms to some extent turns platform labor into a mere appendage of machines, leaving little room for negotiation and adjustment.

It can be said that in the era of AI, the algorithm systems in platform labor have gradually replaced the functions of traditional management, taking on the tasks of tracking, evaluating, constraining, and rewarding platform workers while eliminating the possibility of workers reducing productivity by slowing down labor speed to disrupt capital circulation. However, paradoxically, the relationship between algorithm systems and platform labor also contains a dependency relationship, where the massive flow of labor data in real-time monitoring continuously feeds back into the algorithm systems, filling gaps and making them increasingly intelligent, leading to more precise and meticulous labor control. Thus, the traditional process of human “taming” of technology is inverted in platform labor, where algorithmic technology tames workers, and intelligent labor control further strengthens the dominance of technology, while platform workers are trapped by algorithms.

(3) Excessive Competition: Ensuring the Reproduction of Labor Consciousness

American scholar Michael Burawoy argues that management’s labor control should not be absolutized, reducing “workers to manipulated objects, commodities bought and sold in the market, and powerless abstract collections”. In fact, platform workers under surveillance are not entirely passive; they possess a certain agency, attempting to weaken the algorithmic control imposed by the platform in the complex and fluid labor space and subtly contesting interests by exploiting system loopholes. Therefore, AI-driven platform enterprises, in order to effectively maintain the normal operation and long-term survival of platform labor, not only employ external control methods such as technical management and disciplinary punishment but also ideologically reinforce the reproduction of labor consciousness among platform workers. This is because the subjective organization of consent is necessary to induce workers to have a willingness to cooperate in the process of transforming labor power into labor. For management, only by unifying external institutional norms with workers’ internal psychological recognition can the reproduction of the entire platform labor be ensured.

Marx believed that due to the popularization of machines and the simplification of labor, if “workers want to maintain their total wages, they must work more: work a few more hours or provide more products in one hour”. Platform labor mostly belongs to simple labor, characterized by low skill requirements, high repetition, and high mobility. To strengthen labor stickiness and production sustainability, platforms typically establish a competitive labor mechanism supported by intelligent algorithm systems. Platforms use point upgrades, incentive subsidies, and leaderboard rankings to endow intelligent labor mechanisms with game attributes, thereby stimulating platform workers’ enthusiasm for participation and encouraging them to actively engage in the new “piece-rate” labor competition. Burawoy refers to this as the “game of making out”; when each worker “tries to reach the production level that can earn incentive wages”, their agency can be fully realized as they consciously extend their working hours or improve labor efficiency to strive for excess income. Essentially, excessive labor competition sets up an endless game for platform workers, including food delivery riders and ride-hailing drivers, where they “level up” while gradually internalizing the game rules set by the platform, and their active engagement further promotes the reproduction of labor consciousness.

The platform designs gamified and competitive labor mechanisms to hide the external systemic exploitation within the “play” structure that platform workers actively participate in. This is a labor competition under the regulation of intelligent technology, as well as a daily enactment of platform rules, aimed at making the platform labor process competitive, encouraging them to exert effort beyond the average level to earn excess income while testing the physical and psychological limits of platform workers. In the view of Byung-Chul Han, this indicates that the logic of exploitation in platform labor has exhibited new characteristics distinct from traditional exploitation methods, namely, “exploitation no longer appears in the form of alienation and self-realization deprivation, but is cloaked in the guise of freedom, self-realization, and self-improvement… I willingly exploit myself”. However, this overt self-exploitation is not an active choice of platform workers but a passive adaptation to the tightly controlled technological structure and increasingly harsh employment market, and the underlying structural dilemmas cannot be ignored.

(4) Automatic Regulation: Achieving Dehumanized Labor Exploitation

The combination of digital platforms and unconscious consumption patterns makes it easy for people to habitually overlook the human labor behind the platform. However, in reality, the platform architecture and its embedded AI systems can only operate with the support of various platform workers, thereby regulating the process, logic, and rhythm of platform labor in real-time. In food delivery platforms, the expansion of the rider workforce increases the platform’s flexibility and uncertainty. To stabilize the large rider group, both the methods of labor regulation and the management mechanisms for workers need to undergo intelligent upgrades, making platform labor stable, controllable, and sustainable.

Labor management in the production process aims to strengthen capital’s control over workers, fully mobilizing workers’ agency to improve the efficiency of surplus value exploitation, with machine systems or technical systems playing a crucial role. Marx pointed out that factory labor under machine production is “driven by an automatic machine, powered by a self-operating force. This automatic machine consists of many mechanical organs and intelligent organs, thus, workers themselves are merely conscious limbs of the automatic machine system”. In machine-dominated production processes, workers are forced to become appendages of automation, and coupled with management’s labor regulation through technical means, they develop a “dual dependence on machines and labor organization (which is also a kind of machine), leading to a situation where humans become like parts of machines”. Workers must follow the internal logic and rhythm of machines to perform labor.

AI-driven platform labor achieves not only the transition from “machine dominance” to “intelligent dominance” but also the advancement from automated production to automated regulation through panoramic surveillance of the labor process, precise control of labor rhythm, and continuous production of labor consciousness. As American scholar Pedro Domingos stated, the industrial revolution was the automation of manual labor, the information revolution was the automation of part of mental labor, while AI based on machine learning is the automation of automation itself. It should be emphasized that the embedding of machine systems and AI in labor aims to achieve the systematization, automation, and dehumanization of exploitation, but the former has not achieved this goal in factory labor. The reason lies in the fact that in traditional industrial production, machine systems participate as production factors but cannot regulate the labor process, which still relies on hierarchical structures and a large number of direct or indirect labor managers. In contrast, AI-supported platform labor transforms labor exploitation into a process of automatic operation, self-correction, and iterative evolution through a set of intelligent control systems established by flat structures and technical experts, gradually realizing the dehumanization of labor exploitation.

3. The Social Impact of Intelligent Platform Labor

Platforms, as a network-based industrial organization method, have the structural characteristics of optimizing resource allocation and connecting and activating relatively dispersed production factors such as material, information, human resources, and capital, but they also highly rely on the underlying support of intelligent algorithm technologies such as big data, cloud computing, the Internet of Things, and machine learning. Regarding the significance of algorithm embedding in platform labor, French scholar Cédric Durand pointed out that “it is the power of algorithmic feedback loops—reputation, real-time adjustments, simplicity, behavior history records, etc.—that endows these services with special properties, which decentralized producers cannot obtain”. AI-driven platform labor, by strengthening the technical control of relevant algorithm models over the labor process and decision support for labor management, further amplifies the operational advantages of platform economy, resulting in a series of positive social impacts. These mainly include three aspects: first, effectively improving the production efficiency of the platform. The intelligent allocation system supported by algorithms optimizes the distribution of transport capacity or labor supply in different areas by real-time collection and analysis of labor process data, and maximizes the compression of circulation time based on fine control of labor links, thereby reducing human waste and enhancing production efficiency. At the same time, AI systems replace traditional human management models, achieving automation and intelligence in platform labor management, effectively reducing management costs. Second, significantly improving the labor conditions of the platform. Platform workers often face complex real-world environments, and relevant AI-assisted applications can help them cope with the uncertainties of the labor process. For example, the intelligent voice assistant developed by food delivery platforms allows riders to complete basic operations such as order acceptance, feedback, and confirmation through voice dialogue while delivering, avoiding safety hazards caused by operating smartphones during driving. Third, greatly lowering the employment threshold of the platform. The comprehensive embedding of AI systems promotes the automation of a series of task links, operational elements, and delivery processes encompassed by platform labor, thus requiring less knowledge, skills, and experience from workers, allowing them to quickly start work without cumbersome labor training. The continuously lowering employment threshold of intelligent platform labor helps absorb a large surplus labor force in society, fully leveraging the platform economy’s function as a “stabilizer for employment”. It is worth noting that while intelligent platform labor brings many positive social impacts, it also exacerbates the risks faced by platform workers in terms of employment dependency, physical and mental health, and labor protection.

(1) Intensifying Employment Dependency Risks Under Monopoly Conditions

Digital platforms make it possible to organize complex labor divisions and production links online by widely absorbing scattered labor forces. The deep embedding of AI further strengthens the fine management and automatic regulation of platform enterprises over platform workers and their labor processes. Due to the continuous support of technical capabilities, talent reserves, and capital investment required for the operation and maintenance of AI systems in platform production, platforms with relatively limited resources and scale are likely to be merged or even crushed in the “arms race” of intelligence, thereby reinforcing the trend of monopoly in the platform labor market. It is precisely due to the support of intelligent technology that competitive monopolistic behaviors in the platform labor field can often be quickly achieved and consolidated, with the risks and harms being more hidden and complex, such as the abuse of market dominance or restrictive trading behaviors through algorithms.

From the employment perspective, monopolistic behaviors will also hinder the reasonable and orderly flow of workers in the platform labor market, further reinforcing their disadvantaged occupational status. In the express delivery industry, area supervisors clarify the unequal relationship between platform enterprises and workers through daily admonitions to couriers, stating, “The company can do without you, but you can’t do without the company!” “It’s not about how great you are; it’s the platform that gives you the opportunity!” “Have you ever pulled passengers yourself? It’s all the platform that assigns orders to you!” “Don’t think it’s impossible without you; anyone can do it!”. This is because platform labor driven by AI relies heavily on algorithms at every link, and workers can only mechanically undertake corresponding physical labor according to algorithmic instructions, accumulating no valuable work experience and possessing extreme substitutability in the labor market. Coupled with information asymmetry and the significant gap in technical invocation capabilities between workers and platforms, the space for workers to negotiate with platforms regarding labor rights, labor compensation, and reward and punishment rules is gradually shrinking. This not only leads to a power imbalance between workers and platforms but also accelerates the oligopolization of the platform labor market, ultimately intensifying platform workers’ dependency on a few or even a single platform. In addition, the deep application of AI technology in the platform economy may also trigger a new wave of employment replacement in the platform labor market. According to a report released by the McKinsey Global Institute in 2024, it is estimated that by 2030, AI will automate 30% of working hours under a medium adoption scenario, posing severe technological replacement risks for low-skilled jobs, including platform labor.(2) Intensifying Physical and Mental Health Risks Under Algorithmic Control

The core of AI embedding in platform labor is the replacement of human managers by algorithms that automatically adjust and digitally control all elements and links of the platform labor process, while making workers internalize the production structure of the platform in their daily labor practices. In reality, platform workers passively participate in the creation and optimization process of algorithms through real-time transmission of labor data, but platforms often use these “co-created” algorithms to further strengthen labor command, labor control, and automatic rewards and punishments in the labor process, thereby continuously exacerbating the technological alienation of platform workers and their physical and mental health risks during labor.

In ride-hailing platforms, algorithm systems utilize drivers’ trip information feedback to optimize transport capacity layout, automatically regulating drivers’ work performance through immediate incentives or punishment mechanisms. It even indirectly transforms some labor-capital conflicts into conflicts between drivers and users due to information asymmetry under the “algorithmic black box”, causing drivers to frequently find themselves in real disputes with passengers over platform rules. In food delivery platforms, the algorithm system controls the distribution of delivery orders, and riders must comply unconditionally; refusing the algorithm’s mandatory distribution will lead to a decrease in the total number of orders they can accept. Meanwhile, riders must also strive to meet the accelerated demands dictated by the algorithm’s rationality during the delivery process. The poet Wang Jibing, known as the “food delivery poet”, wrote in his poem “The One in a Hurry”: “Chasing the wind out of the air / Chasing knives out of the wind / Chasing fire out of the bones / Chasing water out of the fire / The one in a hurry has no seasons / Only a stop and the next stop”. The stringent time requirements, coupled with the algorithm’s delayed response to the complexity and dynamics of real environments, expose riders to personal accident risks, including traffic accidents and sudden death from overwork. Statistics show that in Shanghai, the number of traffic violations in the express delivery and food delivery industry exceeds 17,000 per week, with food delivery riders accounting for about 90% of these violations, resulting in countless casualties.

(3) Intensifying Labor Protection Risks Under Flexible Employment

Many platform workers do not have formal employment relationships with platform enterprises; platform enterprises mainly profit by charging information rents during the production process, thus platform workers, including food delivery riders and ride-hailing drivers, are often regarded as independent contractors matching supply and demand through the platform. From a business perspective, this business model of introducing independent contractors through platforms allows platform enterprises to create highly flexible and on-demand labor at extremely low fixed costs while evading the constraints of labor laws and related social security systems, structurally reducing the protective rights of these flexible workers. Platform workers engage in de facto employment labor for platforms and accept strict labor control, yet some platforms fail to assume corresponding labor protection responsibilities, leading to increasingly prominent issues such as overwork and lack of effective channels for labor rights complaints. For example, food delivery riders not only face urgent pressure to meet delivery deadlines but also must extend their working hours to increase order volume and improve performance metrics to earn incentive income under the competitive mechanisms designed by the platform, thereby exacerbating the risk of overwork. Moreover, when food delivery riders receive complaints or negative reviews from users due to uncontrollable factors, they often lack reasonable and effective mechanisms to protect their legitimate labor rights. It is evident that the internal labor rights protection within platforms remains weak, and platform workers often lack clear legal norms and systematic adherence to external social security regarding issues such as work injury recognition, labor disputes, medical insurance, and unemployment assistance.

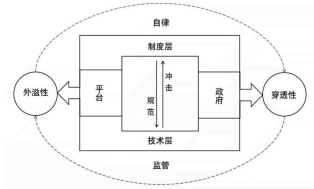

4. Multi-Dimensional Governance Paths for Platform Labor

In recent years, government departments have successively introduced a series of policy documents regarding the healthy development of the platform economy, conducting multiple rounds of comprehensive governance actions around prominent issues in the field of platform labor. However, a systematic examination of the governance experiences of platform labor, in light of the new changes in operational mechanisms under the accelerated development of generative artificial intelligence, reveals several urgent research and resolution issues. Fundamentally, the key to solving these problems lies in adhering to the principle of “AI for good”, establishing and improving a regular regulatory system, avoiding the pitfalls of “over-regulation leading to stagnation and under-regulation leading to chaos”, and better safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of platform workers while promoting the growth and strength of the platform economy. Currently, the governance of platform labor should particularly focus on researching and resolving the following issues: 1. How to clarify the boundaries of governance responsibilities for platform labor and address the issue of inadequate implementation of platform主体责任? 2. How to break the contradiction between the externalities of platforms and the impermeability of platform governance, enhancing the collaborative governance effectiveness of industry regulation and local regulation? 3. How to reduce sudden and passive governance, enhancing the transparency, stability, and predictability of platform governance? 4. How to confront the contradiction between the advanced nature of technological development and application and the lag of regulatory systems, better releasing the vitality of the platform economy as a new productive force under AI conditions? Based on this, the following systematic governance measures will be proposed around key issues in platform labor from different dimensions, including platforms, government, institutions, and technology (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Multi-Dimensional Governance Paths for Platform Labor

(1) Platform Dimension: Strengthening Platform Responsibility and Promoting Compliance Operations

As pioneers in the research, incubation, innovation, and application of AI, platform enterprises often apply relevant technological achievements to enhance their production organization efficiency and market competitiveness before the current regulatory system is updated, and platform labor is no exception. While continuously expanding their user base, platform enterprises also expand a large number of workers providing corresponding services, including food delivery riders and ride-hailing drivers, thus forming a dual monopoly tendency on both the user and labor sides. The former aims to attract user groups through price advantages and cultivate their consumption habits, while the latter seeks to suppress other similar platform enterprises and limit market competition, objectively reducing workers’ alternative choices in the platform labor market, thereby weakening the bargaining power of platform workers and enhancing their work stickiness. Compared to other industries, platform labor driven by AI further strengthens the technical advantages of platform enterprises, and the structural embedding of digital platforms in people’s daily lives also results in stronger spillover effects. In light of this, it is essential to strengthen platform responsibility, clarifying that platform enterprises are the primary responsible entities for the embedding of AI in platform labor, and to simultaneously enhance their compliance construction during the application of AI technology, avoiding technical processes such as data acquisition, labor monitoring, and algorithm analysis that violate current laws and labor protection requirements. At the same time, it is necessary to actively construct a governance system that promotes the compliant application of AI within platform enterprises, ensuring that the legitimate rights and interests of workers are not overlooked in the process of rapid technological iteration, utilizing AI technology to improve platform labor conditions, and striving to resolve conflicts and disputes between platforms and workers through the “humanization” of technology.

(2) Government Dimension: Implementing Local Regulatory Functions and Forming Government Governance Synergy

The embedded impact of AI technology on platform labor methods, processes, and controls, as well as the series of social risks arising from it, have exceeded the scope of simple enterprise management and cannot be resolved solely through platform self-regulation. Government functional departments must further strengthen regulation, scientifically assess the speed of AI technological advancement, the intensity of political and economic impacts, and the degree of social tolerance. While refining the regulatory dimensions of platforms, it is necessary to break the traditional governance approach of “fragmentation” and, focusing on the key, difficult, and painful points emerging in the governance of platform labor in the AI era, break down departmental barriers, unite various forces, and effectively address prominent issues in the field of platform labor, enhancing the level of multi-departmental collaborative governance. Relevant industry authorities should promptly issue compliance management measures for the application of AI technology in platform labor, actively regulating the unfair competition strategies adopted by platform enterprises to seize user groups, while vigorously rectifying the behaviors of platform enterprises that excessively utilize algorithms, platform rules, and information advantages against workers, effectively playing the government’s regulatory role while fully respecting the market’s self-adjustment principles, ensuring that the platform labor market operates within the legal framework, and supporting business entities to participate in competition in an orderly manner according to the law. Meanwhile, platform enterprises possess dual attributes of enterprises and platforms; as legal entities, they primarily rely on local management, while the networked, expansive, and broad nature of platforms requires a comprehensive consideration in the governance process. Historically, platform governance has mainly relied on industry authorities for vertical management, lacking effective intervention and cooperation from local governments. Therefore, it is essential to solidify the local regulatory functions of platform labor governance, requiring local governments to take proactive roles and actions, forming a governance synergy between industry authorities and local governments, systematically resolving the contradictions between platform externalities and the impermeability of regulation.

(3) Institutional Dimension: Strengthening Institutional System Construction and Enhancing Governance Predictability

Whether through platform self-regulation or government regulation, governance should not remain at the level of “stimulus-response” logic but should further strengthen the construction of institutional systems for platform governance, enhancing the stability and predictability of platform governance. For platforms themselves, they should use relevant laws and regulations as guidelines and policy spirits to actively construct internal compliance systems, while also involving social forces to promote the construction of health development indicators for platform enterprises and reasonably assess their responsibility fulfillment. For government departments, it is necessary to fully leverage the efficiency of agile governance in addressing prominent issues in the platform economy while also focusing on elevating past governance experiences into institutional regulatory frameworks, providing predictable standard references for the compliance construction of platform enterprises, and actively incorporating the needs and suggestions of stakeholders such as platform enterprises, platform workers, and platform users to enhance the transparency of platform governance. Specifically regarding platform labor governance, due to the independent contractor nature of platform workers, many traditional labor protection systems often face challenges in effective applicability. Therefore, it is crucial to pay special attention to the protection of the legitimate rights and interests of platform workers, ensuring that they receive necessary protections in platform labor, have the autonomy to decide whether to disconnect without being placed at a disadvantage, and enjoy rights to insurance and compensation in the event of work-related injuries. At the same time, the principle of “digital equity” should be regarded as the fundamental principle for constructing platform labor systems in the era of AI, actively promoting the establishment of a new social security system that adapts to the labor forms of platform labor, comprehensively considering the particularities of platform enterprises in terms of employment absorption, labor scale, and innovative development, as well as the highly decentralized, networked, and intelligent characteristics of platform workers in terms of labor locations, processes, and organizational methods, to build a flexible and adaptable social security system for platform workers.

(4) Technical Dimension: Realizing Multi-Party Collaborative Governance to Drive Positive Technological Development

The embedding of AI in platform labor also shapes the social operation logic through emerging technologies via the platform economy, involving the government, enterprises, workers, and consumers. Therefore, it is essential to drive the positive development of AI technology in platforms through collaborative governance involving multiple stakeholders. The core of AI technology is machine learning algorithms, which, as a data-driven technical system, serve as both decision-makers for platform production and enforcers of platform discipline. The combination of these technical and regulatory attributes forms a dominant algorithmic power over platform labor, and the key to AI technology governance is actually algorithm governance. Algorithm governance in the context of platforms must adhere to a human-centered application orientation, involving multiple stakeholders, including platform enterprises, government departments, and labor organizations, to conduct comprehensive governance throughout the entire process of algorithm design, operation, feedback, and updates related to platform labor. Among them, enterprise stakeholders can establish an algorithm risk assessment team composed of professional technical personnel, technology ethicists, and legal experts to regularly self-assess the performance of platform labor-related algorithm systems in terms of fairness, non-discrimination, transparency, and humanization, and make improvements based on assessment results, thereby embedding positive social values into the design principles and operational processes of platform algorithm systems. Government stakeholders can establish dedicated technical departments responsible for managing the algorithm applications of relevant platform enterprises, promoting the legal, compliant, and reasonable use of AI technology in platform labor. Labor stakeholders can actively participate in the algorithm system negotiation process by forming new types of labor unions, ensuring that platform workers’ voices and subjectivity are fully represented in the construction of algorithms, avoiding the habitual neglect of labor groups in AI technology governance.

Conclusion

Currently, platform labor can mainly be divided into remote labor and on-site labor, with the former often being global crowdsourced labor without strict geographical limitations, while the latter involves circulation labor with strong peripheral characteristics. Compared to the former, on-site labor faces more complex labor scenarios, tighter labor controls, and greater labor risks. The embedding of AI in platform labor is primarily reflected in on-site circulation labor represented by food delivery, express logistics, and ride-hailing services. Whether it is the intelligent decomposition, matching, and management of order tasks, or the panoramic surveillance, algorithmic taming, and excessive competition in the labor process, all rely on the technical support of AI systems, thereby achieving fine control and automatic exploitation of platform labor by digital capital. Essentially, as a “new organizational management form aimed at enhancing operational speed”, the operational mechanism of platform labor dominated by AI also reflects the acceleration of social processes in the digital economy. While this mechanism can effectively improve the production efficiency of all factors in the platform, it also continuously exacerbates the risks faced by platform workers in terms of employment dependency, physical and mental health, and labor protection within an almost “airtight” labor order. In light of this, regarding the negative effects arising from the embedding of AI in platform labor, multiple stakeholders should adhere to the principles of “technology for good” and “people-centered” governance, conducting prudent governance through multi-dimensional governance measures that include platform self-regulation, government supervision, institutional construction, and technological co-governance, fully leveraging the technological advantages of AI in leading the innovative development of the platform economy while reducing the social risks arising from the embedding of AI in platform labor.

Journal of the Party

School of the Central

Committee of the C.P.C.

(Chinese Academy of Governance)

National Social Science Fund Sponsored Journal

National Core Chinese Journal

Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) Source Journal

Authoritative Journal of Chinese Humanities and Social Sciences

Submission Platform for the Journal of the Party School of the Central Committee of the C.P.C.

https://zgxb.cbpt.cnki.net/WKE/WebPublication/index.aspx?mid=ZGXB