Hello everyone, welcome to my column.

In previous articles, we explored the benefits of Thread-Level Parallelism (TLP) and the classifications of TLP architectures.

Today, let’s learn about the cache coherence problems faced by shared memory architectures.

Table of Contents

1. Shared Memory Architecture

2. Cache Coherence Problems

Table of Content

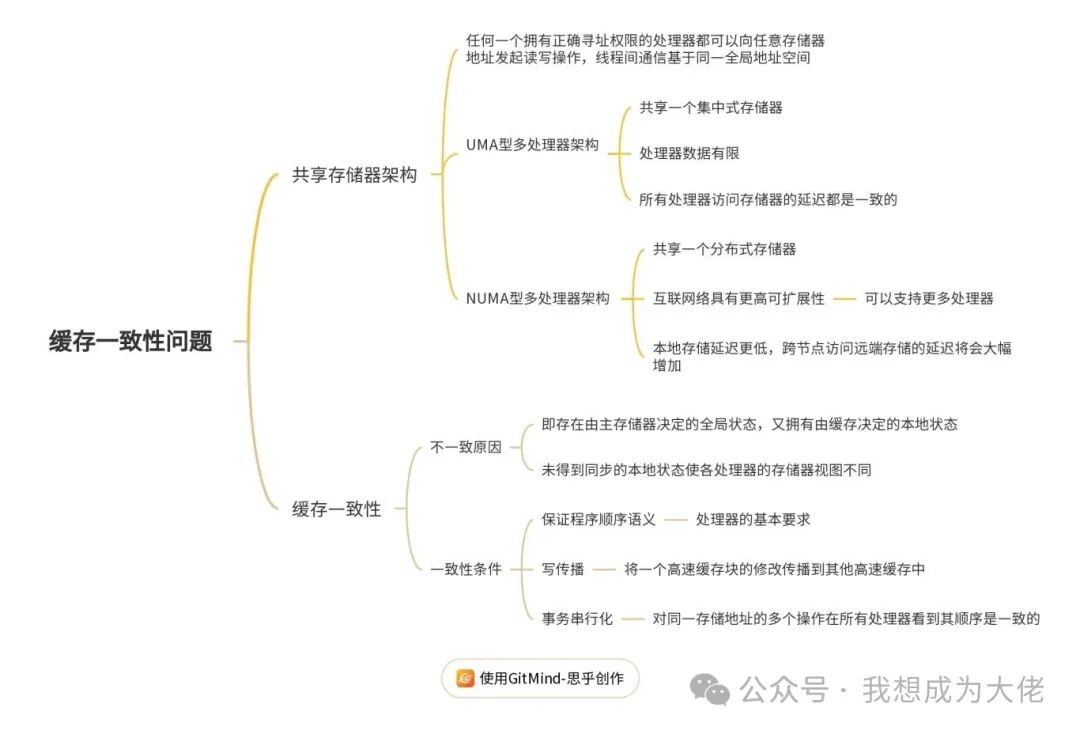

Mind Map

01Shared Memory ArchitectureShared memory architecture

01Shared Memory ArchitectureShared memory architecture

This series, <Breaking the Single Processor Bottleneck: How Thread-Level Parallelism Reshapes the Future of Computing?>, introduces four classifications of MIMD architecture: shared cache, Uniform Memory Access (UMA), Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA), and distributed computer architecture.

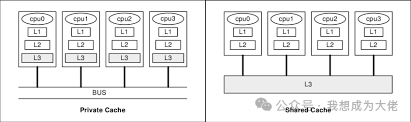

Figure 1: Private and Shared Cache Architectures

As the number of cores on a chip continues to increase, the engineering challenges of a purely “fully shared” cache architecture rise sharply in terms of bandwidth, latency, power consumption, and scalability.

Therefore, even though modern multicore CPUs physically design L2/L3 as shared, they still reserve private L1 (and in some designs, private L2) caches for each core, balancing ultra-low latency and high-capacity sharing through a hierarchical cache system.

At the single physical chip level, this private + shared hierarchical cache is precisely the embodiment of UMA-type multiprocessor architecture in on-chip multicore environments..

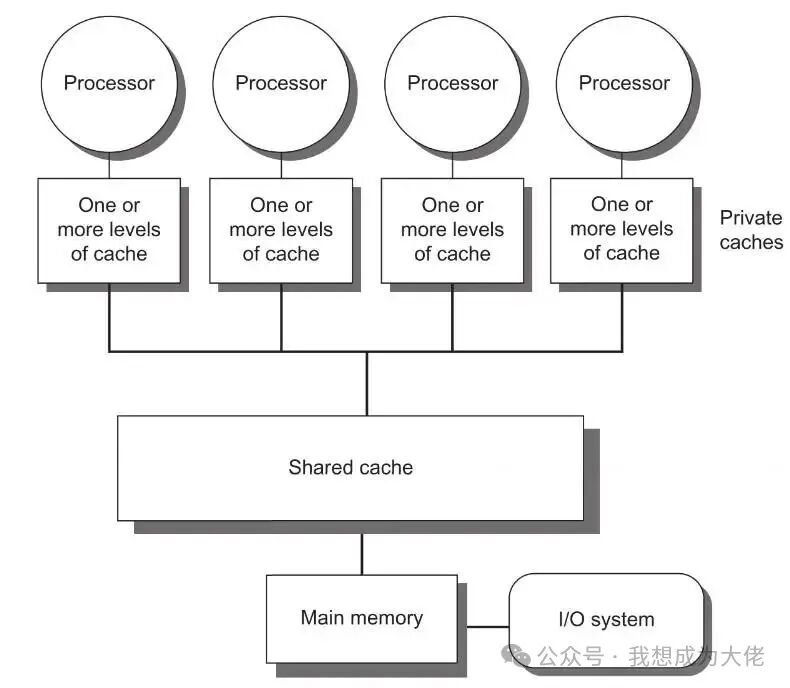

Figure 2: UMA-type Multiprocessor Architecture

UMA-type multiprocessor architectureshares a centralized memory, and all processors access memory with consistent latency.

The characteristic of UMA-type multiprocessor architecture is that all processors are interconnected through the same centralized main memory; however, the bandwidth and latency bottlenecks of centralized interconnectlimit the number of cores in the system, typically 8–16 cores, with a few high-end systems achieving 32 cores.

Figure 2 provides a block diagram of the UMA architecture for multicore chips; multi-chip systems can also apply the UMA architecture by omitting shared caches and connecting multiple processors to memory via inter-chip interconnect networks.

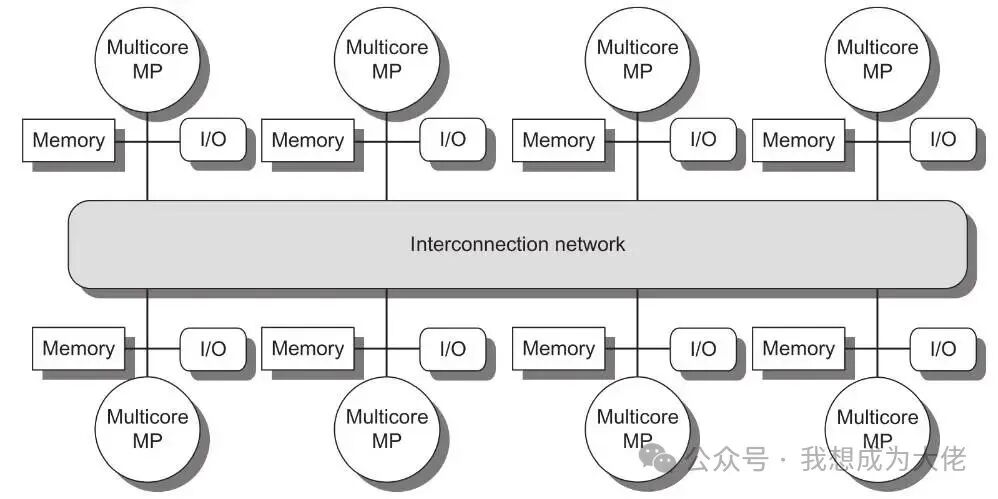

Figure 3: NUMA-type Multiprocessor Architecture

NUMA-type multiprocessor architecturedistributes memory across processors, and all processors share a distributed memory.

The distributed memory of NUMA-type multiprocessor architecture allowslower latency for local memory access within nodes, while accessing remote memory across nodes incurs significantly higher latency. At the same time, due to the interconnect topology used in NUMA-type multiprocessor architecture havinghigher scalability, it can easily exceed 32, 64, or even hundreds of cores.

Both UMA and NUMA multiprocessor systems areshared memory architectures, meaning thatany processor with the correct addressing permissions can initiate read and write operations to any memory address, and inter-thread communication is based on the same global address space.

In contrast, distributed computing appears more like independent computers connected via a network; if there is no software protocol running between two processors, one processor cannot access the memory of another processor. This part of the discussion will be covered in the subsequent content of this series.

02Cache Coherence ProblemsCache Coherence2.1Error Scenarios

The data used for thread communication in shared memory architecture is calledshared data, which can be used by multiple processors. In contrast, data provided for single processor use is calledprivate data.

Processors in UMA and NUMA multiprocessor systems have private caches. When private data is cached, it can reduce its average access latency and lower memory access bandwidth. Since other processors do not access it, the program behavior is consistent with that in a single processor.

When shared data is cached, in addition to optimizing latency and bandwidth, it can reduce memory address contention and lower conflicts, but it introduces cache coherence problems.

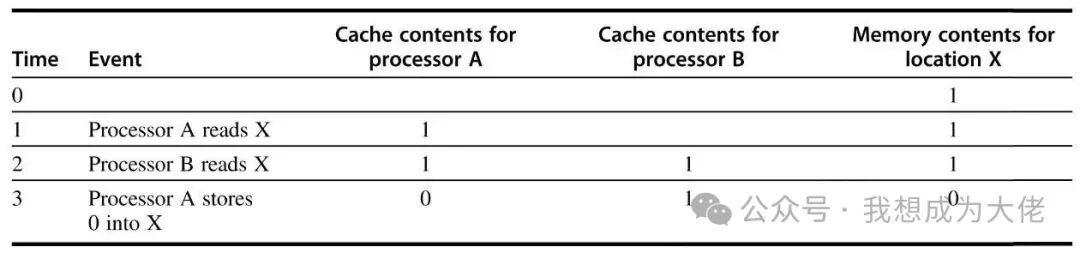

Figure 4: Cache Inconsistency

Initially, it is assumed that both processor A and processor B’s local caches contain data from memory address X, with a value of 1. The cache uses a write-through policy. After processor A writes 0 to memory address X, both cache A and main memory contain the new value, but cache B still holds the old value. Processor B reading memory address X cannot read the value 0.

2.2Error Causes

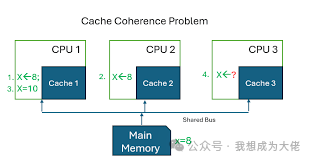

Figure 5: Different Memory Views

The cause of this problem is that two different processors maintain their memory views through their respective caches; if there is no hardware or software-level synchronization mechanism (such as a cache coherence protocol) to invalidate or replace stale copies with new values, theneventually different memory views may be observed. The fundamental issue is:there exists a global state determined by main memory and a local state determined by caches.

2.3Correction Methods

The problem that cache coherence aims to solve is: the values seen for the same data in different caches are inconsistent, meaning a unique shared memory abstraction cannot be achieved. In simple terms,if the latest written value of a data item is returned every time it is read, then the memory system is said to be coherent.

This simple explanation includes two behaviors of shared memory systems:coherence and consistency.

Coherence determines what value a read operation may return, i.e., the latest written value.

Consistency determines when a written value is returned by a read operation.

To support coherence, three conditions must be met

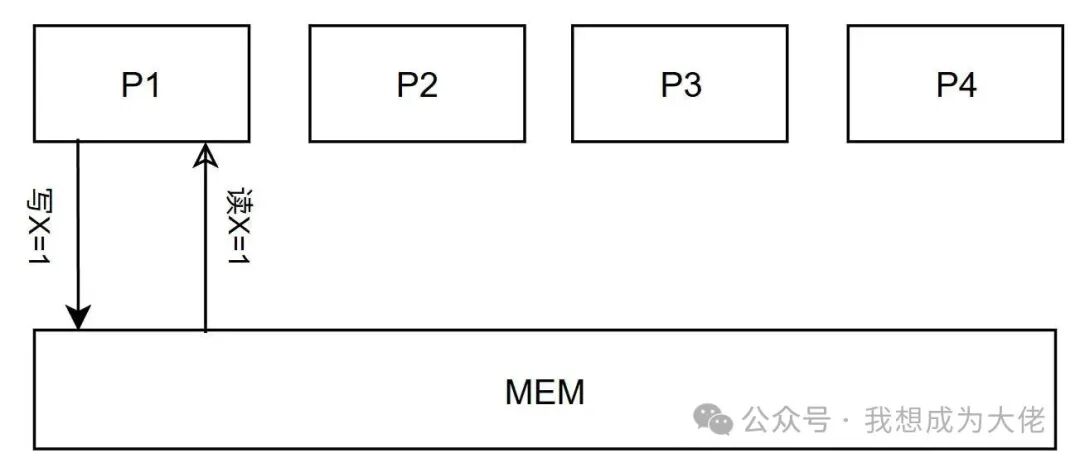

Figure 6: Coherence Condition 1: Satisfying Program Order Semantics

Processor P reads memory address X, which was previously written by P; if no other processor writes to memory address X between P’s write and read operations, then thisread operation will always return the value written by P

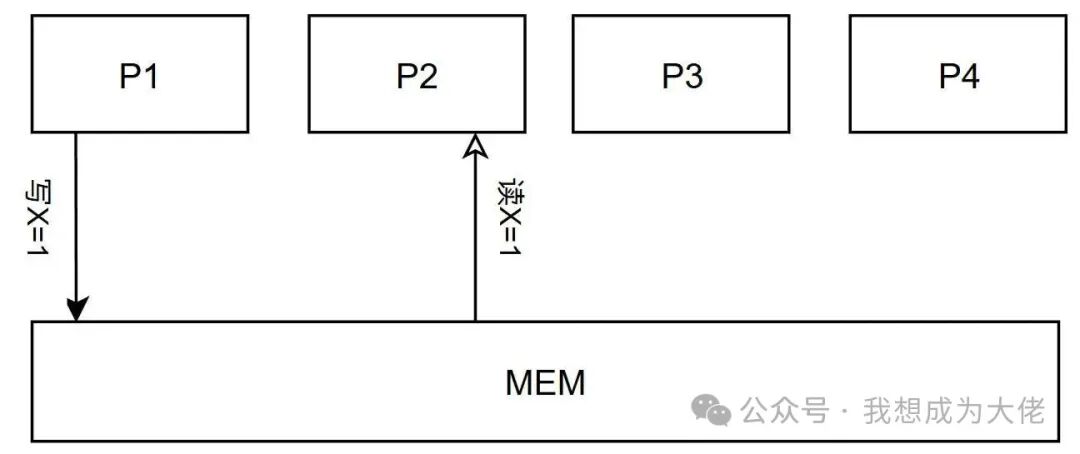

Figure 7: Coherence Condition 2: Other Processors Can Read New Values

After processor P1 writes to memory address X, processor P2 reads memory address X; if the read-write interval is long enough and no other processor writes to X between the two accesses, thenP2’s read operation will always return the value written by P1

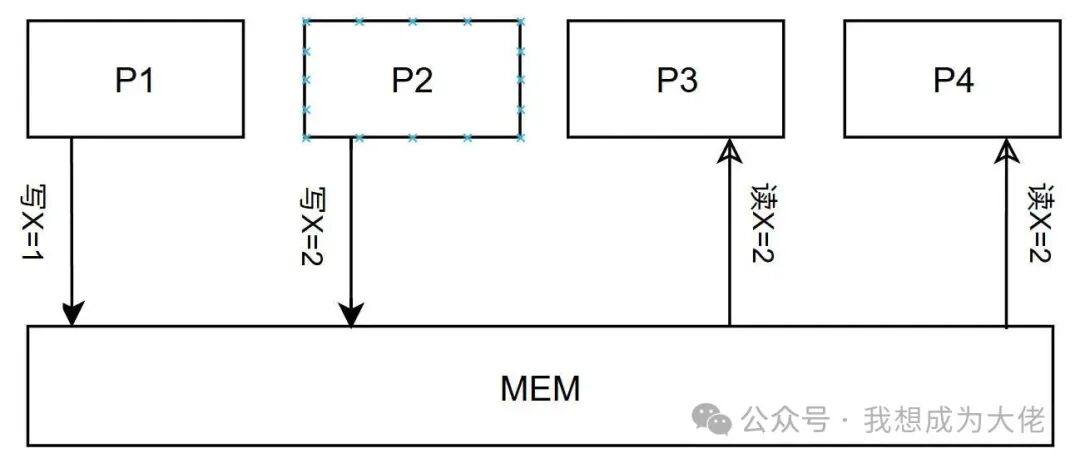

Figure 8: Coherence Condition 3: Processor Write Operations Are Serialized

From the perspective of all processors, any two processors performing two write operations to the same memory address appear to be in the same order. For example, if processor P3 sees the memory write order as P1 writing first and P2 writing second, then the final read value is P2’s written value. Thus,P4 and other processors will not see any other order, meaning the final read value is also P2’s written value.

The first condition requiresmaintaining program order semantics, which must be satisfied even in single-processor systems.

The second condition requires multiprocessor systems to supportwrite propagation,propagating modifications of a cache block to other caches

The third condition requires multiprocessor systems to supporttransaction serialization,ensuring that multiple operations on the same memory address are seen in a consistent order by all processors.

Determining when a written value can be seen is also a crucial issue.

We cannot require that after processor P1 writes a value to X, processor P2 can immediately see this value, as the written value may still be in P1’s local cache, or the write request transaction may still be propagating on the bus.

So how long after a write must the value be readable by a read operation? This falls under the category of memory consistency, which we will discuss in the subsequent content of this series.

Thank you for reading and accompanying me. This article provides a comprehensive introduction to the cache coherence problems and coherence conditions faced by shared memory architectures, and I hope it is helpful to you. Feel free to share your opinions and thoughts in the comments section, and you are also welcome to join our discussion to exchange ideas.

Previous links:

Breaking the Single Processor Bottleneck: How Thread-Level Parallelism Reshapes the Future of Computing?