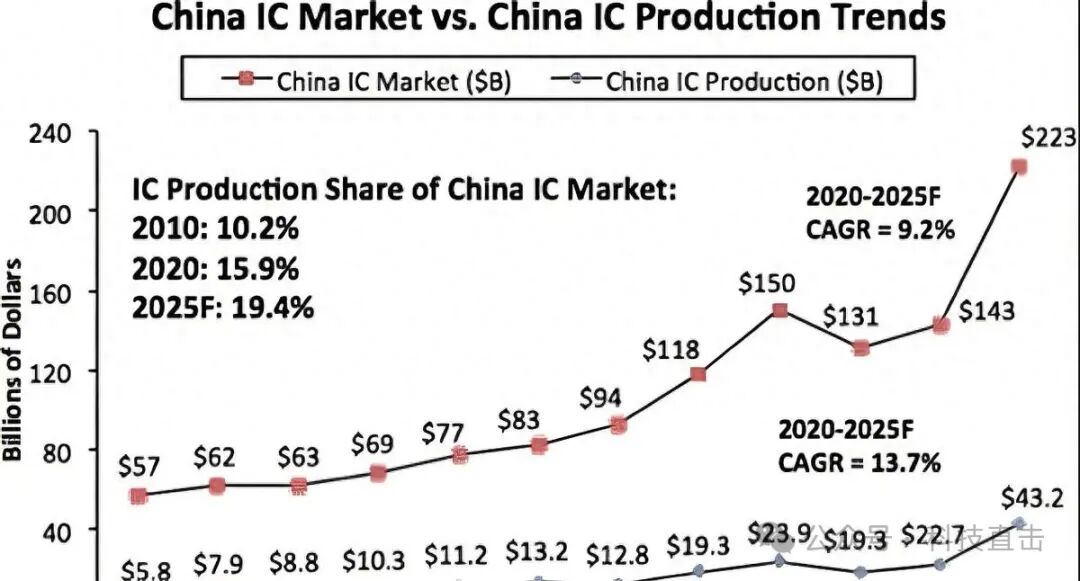

Those South Korean friends who always say “South Korea crushes China” have recently been harshly confronted in the chip sector. In the first two months of 2025, China’s semiconductor exports reached $25.1 billion, surpassing South Korea’s $19.7 billion for the first time.

This is not a coincidence, but the inevitable result of a decade of technological accumulation.

Surpassing in Numbers

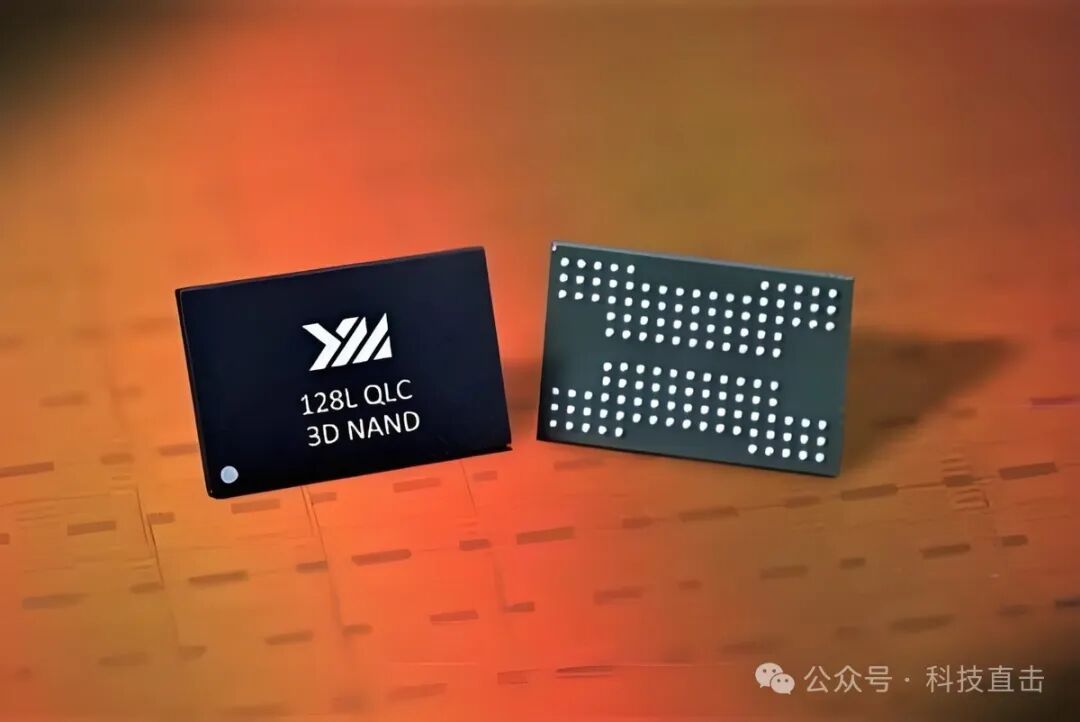

First, let’s look at some astonishing data: Yangtze Memory Technologies has achieved 294-layer 3D NAND flash technology, which is considered top-level in the global memory chip field; Huawei’s Ascend 910B AI chip performance has reached 60% of NVIDIA’s H100, and this achievement was made under comprehensive sanctions from the United States.

What does this mean? It means that China has achieved a structural lead over South Korea in at least 11 key technology points.

“Wait, why do I feel like just a few years ago it was said that ‘China’s chips are ten years behind South Korea’?”

That’s right, changes happen so quickly! From the ZTE incident in 2018 to now, in just a few years, China’s semiconductor industry has completed a transformation from “breakthroughs in isolated points” to “full-chain development.” It is particularly noteworthy that the etching equipment from Zhongwei has entered TSMC’s production line, which was unimaginable five years ago.

And what about South Korea? Samsung Electronics, as the backbone of South Korea’s semiconductor industry, has seen its inventory turnover days increase to 135 days in 2024, indicating serious product backlog. More critically, 80% of South Korea’s etching equipment relies on the American company Lam Research, which poses a “choke point” risk that is particularly fatal in today’s geopolitically tense environment.

Innovation Model Competition

Why has China been able to achieve such a leap in a short time? The core lies in the different modes of innovation.

South Korea’s semiconductor development follows a “technology-following model,” which simply means closely following the technology roadmaps of companies like Intel and Micron, then striving to catch up and attempt to surpass. This model is very effective during the catch-up phase, but once the industry landscape changes, it becomes easy to be constrained. For example, in the case of HBM3E high-bandwidth memory technology, Samsung’s R&D progress is a full year behind Micron.

In contrast, China adopts a “scenario-driven innovation” model. For example, the explosion of China’s new energy vehicle industry has directly created a huge demand for IGBT power chips, prompting companies like BYD to accelerate their self-research in related technologies. This innovation approach, which starts from practical application scenarios, provides clear direction and substantial market support for technological R&D.

The Unexpected Effects of the U.S. CHIPS Act

The U.S. CHIPS Act was originally intended to curb the development of China’s semiconductor industry, but it unexpectedly accelerated the differentiation of the semiconductor industries in China and South Korea.

The act stipulates that South Korean companies receiving U.S. subsidies cannot transfer advanced process technologies to China. This has locked Samsung’s Xi’an factory’s process at 14 nanometers, preventing upgrades. Meanwhile, SMIC has achieved large-scale production of processes below 14 nanometers and made breakthroughs in advanced processes like N+1 and N+2.

More strategically, China has successfully broken through the ARM system blockade through the RISC-V open instruction set architecture. By the end of 2024, China’s RISC-V chip market share has reached 28%, becoming the largest RISC-V chip application market in the world. In contrast, South Korea remains deeply entrenched in the American technology framework.

There is an industry joke that says: “The U.S. wants to choke China’s chips, but ends up hurting South Korea and stimulating China.”

This industry joke reveals the awkward reality of the U.S. CHIPS Act. The U.S. government has invested about $54 billion in subsidies for domestic and allied semiconductor industries, but inadvertently provided China’s chip industry with an opportunity for “forced independent innovation.”

Just look at Samsung’s predicament in China. The Xi’an factory was originally an important base for Samsung’s global memory chip production, with plans for continuous process upgrades, but the CHIPS Act has turned it into a “technology island.” Moreover, South Korean companies face a dilemma: either give up U.S. subsidies and stick to the Chinese market, or accept subsidies but lose the world’s largest semiconductor consumer market. This dilemma is a typical consequence of geopolitical interference in industrial development.

It must be said that the CHIPS Act, this “double-edged sword,” may ultimately harm the long-term interests of the U.S. and its allies while accelerating the independent innovation process of China’s semiconductor industry.

Digital Transformation of Population Dividend

On the surface, the competition between China and South Korea is a technological contest, but at a deeper level, it is a game of population resources.

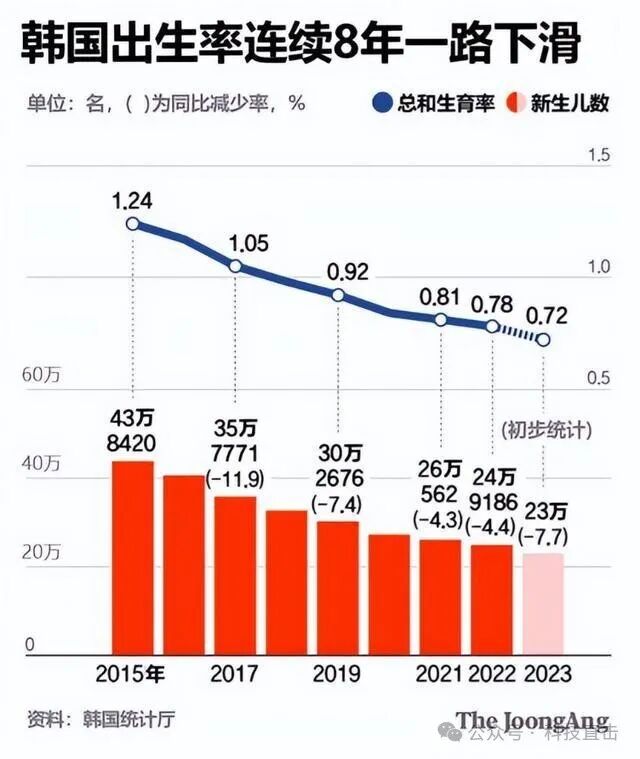

South Korea has relied on the elite education and high-intensity R&D of its 30 million population to create miracles in the semiconductor industry. However, with the acceleration of population aging (South Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world), this development model faces severe challenges.

In contrast, China, with its 1.4 billion population and digital transformation, generates more than nine times the amount of data compared to South Korea every day. This massive data provides a “training ground” for AI chips and algorithm optimization that South Korea cannot match.

It is worth noting that under the RCEP framework, the semiconductor regional supply chain led by China has accounted for 35% of global capacity, which is dismantling South Korea’s traditional model of “two ends outside” (core technology relying on the U.S., market relying on China). Samsung Electronics’ 2024 performance report has already reflected the pressure brought by this trend.

The ultimate manifestation of the population resource game is industrial sustainability. As South Korea’s aging crisis deepens, whether its high-intensity, high-pressure R&D model can be sustained has become a question in the industry. In contrast, the population dividend activated by China’s digital transformation still has a long release period. To some extent, this is a competition between a “sprint runner” and a “marathon runner,” with China’s endurance advantage gradually becoming apparent.

Development Behind Semiconductor Competition

The semiconductor rivalry between China and South Korea essentially reflects the competition between two different industrial development paths.

South Korea’s “memory chip + chaebol” model has achieved great success over the past few decades, with Samsung and SK Hynix becoming global memory giants. However, this highly concentrated model also brings risks; once core enterprises encounter difficulties, the entire country’s technology industry will be impacted.

China, on the other hand, has taken a path of “demand-driven innovation.” From a historical perspective, China’s technological accumulation has continuity, from the two bombs and one satellite to quantum communication, and now to AI chips, reflecting a consistent lineage of independent innovation. South Korea’s technological breakthroughs have relied more on Cold War dividends and globalization, and once it loses the support of the Chinese market, the fragility of its development model becomes apparent.

Interestingly, some South Korean companies are now purchasing patent licenses from China. For example, hybrid bonding technology, which was unimaginable a few years ago. The transfer of industrial chain discourse power is quietly happening.

This competition has also sparked some deep reflections: Will China’s breakthroughs in AI chips trigger concerns about “computing power hegemony”? Will South Korea’s efforts to strengthen semiconductor autonomy further exacerbate the fragmentation of the global supply chain? From the “material level” of technological transcendence to the “institutional level” of innovation ecosystem construction, the China-South Korea competition has entered a new stage.

Conclusion

Looking back at the entire history of the China-South Korea semiconductor competition, we see China’s magnificent transformation from “technological follower” to “parallel competitor” and then to a “leader” in certain fields. This is not a coincidence, but stems from China’s unique path of development: an open and inclusive technological ecosystem, a scenario-driven innovation model, and a collaborative development strategy across the entire industry chain.

Of course, technological competition has never been a zero-sum game. In the future, China and South Korea may achieve complementary advantages in certain areas. After all, in the face of the increasingly complex global chip industry landscape, cooperation and win-win may be a wiser choice.

But one thing is certain: the myth of South Korea “crushing” China has been brutally shattered by the reality of the chip industry. As one netizen joked: “Even the dumplings are being snatched by the Koreans, and this time they fell on chips.”