As developers using the C language, we interact with the main function daily, yet few truly understand the complex mechanisms behind this program entry point. This article will delve into the complete process from program startup to the execution of the main function, revealing key details hidden by the compiler.

1. The Complete Chain of Program Startup

When you type “./a.out” in the terminal and press enter, a series of intricate low-level operations unfold. First, the shell calls fork() to create a new process, then uses the execve() system call to load the executable file. The Linux kernel checks the ELF header of the file, and upon confirming its validity, maps the program segments into the memory address space.

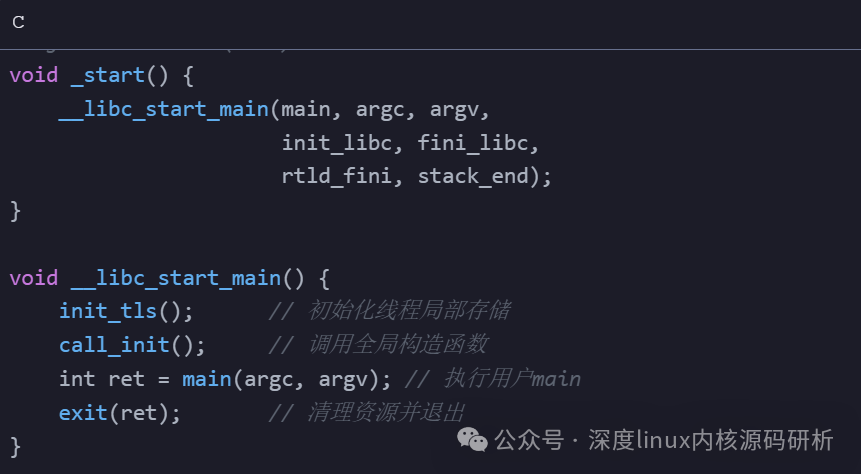

The true starting point of execution is the _start symbol in the .text segment, an entry point automatically inserted by the linker responsible for initializing the C runtime environment. In the implementation of glibc, __libc_start_main() performs the following key operations in sequence:

1. Initialize Thread Local Storage (TLS)

2. Set up Stack Guard

3. Call constructors of shared libraries (.init_array)

4. Register exit handlers (atexit)

5. Prepare the argument environment for the main function

Finally, it calls the user-defined main function

/* glibc internal logic (simplified) */

void _start() {

__libc_start_main(main, argc, argv,

init_libc, fini_libc,

rtld_fini, stack_end);

}

void __libc_start_main() {

init_tls(); // Initialize Thread Local Storage

call_init(); // Call global constructors

int ret = main(argc, argv); // Execute user main

exit(ret); // Clean up resources and exit

}

This process explains why global variable constructors execute before main and why functions registered with atexit can be called upon program exit.

2. The Essence of the Linux Kernel Entry: A Bridge from Assembly to C

The entry point of the Linux kernel is not the C language main, but architecture-specific assembly code (e.g., arch/x86/boot/header.S), which ultimately enters the C language world through the start_kernel function. This process is fundamentally different from the startup of user-space programs (like main):

① User-Space Program Entry (e.g., a.out):

The entry point is _start, inserted by the linker, which calls glibc’s __libc_start_main, completing CRT initialization (global variables, stack protection, parameter passing) before calling main.

It relies on the C runtime library (CRT) and dynamic linker (e.g., ld-linux.so).

② Kernel Entry (using x86 as an example):

Hardware boot: BIOS/UEFI loads the Bootloader (e.g., GRUB), which loads the kernel image (e.g., vmlinuz) into memory.

Assembly initialization: The kernel entry assembly code (startup_32/startup_64) completes the switch from real mode to protected mode, initializes paging, sets up a temporary stack, and finally jumps to start_kernel (C language function). No CRT dependency: The kernel jumps directly from assembly to C, managing memory, interrupts, etc., without glibc support.

3. The Execution Chain of the Linux Kernel C Entry start_kernel

start_kernel is the core of kernel initialization (located in init/main.c), and its execution flow encompasses hardware initialization, core subsystem startup, and user space preparation.

Architecture-independent initialization (C language core)

asmlinkage __visible void __init start_kernel(void)

{

set_task_stack_end_magic(&init_task); // Initialize kernel stack

memblock_init(); // Memory block management initialization

setup_arch(&command_line); // Architecture-related setup (e.g., x86 CPU recognition)

page_address_init(); // Page table address mapping

sort_main_extable(); // Exception handling table sorting

trap_init(); // Interrupt vector table initialization (e.g., page fault)

init_IRQ(); // Initialize hardware interrupts (8259A controller)

softirq_init(); // Soft interrupt initialization (bottom half mechanism)

time_init(); // Clock initialization (8253 timer)

sched_init(); // Scheduler initialization (CFS algorithm basis)

console_init(); // Console initialization (serial/terminal)

// Subsequent: module loading, file system, init process startup…

}

① Detailed Assembly Layer of Function Calls

Let’s analyze the stack frame changes during a function call through a specific example. Consider the following simple function: int add(int a, int b) { return a + b; }

In the x86-32 architecture, the assembly code corresponding to add(3,5) might be:

push 5 ; Push second parameter onto stack push 3 ; Push first parameter onto stack call add ; Push return address onto stack, jump to add

Upon entering the add function, a typical prologue will execute:

push ebp ; Save caller’s ebp mov ebp, esp ; Set new stack frame sub esp, N ; Allocate space for local variables

At this point, the stack layout is as follows: [ebp+12] Parameter b (5) [ebp+8] Parameter a (3) [ebp+4] Return address [ebp] Saved ebp [ebp-4] Possible local variables

This standard stack frame structure allows debuggers to backtrack the call stack and is the basis for implementing variable argument functions.

4. ABI Differences of the main function

Different platforms exhibit significant differences in handling the main function. In the Linux System V ABI, the parameters of main are passed via the stack:

_start: mov (%esp), %ecx ; argc lea 4(%esp), %edx ; argv push %eax ; Possible environment variables push %edx ; argv push %ecx ; argc call main

In contrast, in the Windows x64 ABI, the first four parameters are passed via RCX, RDX, R8, R9: mainCRTStartup: mov rcx, [rsp] ; argc lea rdx, [rsp+8] ; argv call main

More complex is the embedded systems, where in the absence of an operating system, the main function may be called directly by the reset vector, possibly without parameters. These differences require cross-platform developers to pay special attention to portability issues.

5. Modern Compiler Optimization Strategies

Modern compilers have implemented numerous optimizations for the main function. Taking GCC as an example, when it detects that the main function does not use argv, it will optimize away the related parameter passing code. Additionally, the compiler will:

1. Automatically insert stack overflow protection

2. Optimize register allocation based on calling conventions

3. Issue warnings for unused return values

4. Generate special startup code for bare-metal environments

The Clang compiler can even perform inline optimization on the main function; when main only calls one function and immediately returns, it may completely eliminate the stack frame of main.

6. Best Practices for Secure Programming

Understanding these low-level mechanisms is crucial for writing secure code:

1. Stack protection: Enable canary values with the -fstack-protector option to guard against buffer overflows

2. Parameter validation: Strictly check the value of argc to avoid out-of-bounds access to argv

3. Environment isolation: Use secure_getenv() instead of getenv() to prevent environment variable injection attacks

4. Exit handling: Cleanup functions registered with atexit() should maintain idempotency

5. Signal safety: Handlers in exit() should not call non-asynchronous signal-safe functions

It is particularly noteworthy that after the main function returns, the C runtime will also perform the following operations:

1. Call functions registered with atexit in reverse order

2. Flush all standard I/O buffers

3. Execute destructors of shared libraries (.fini_array)

4. Finally, call the _exit system call to terminate the process

These insights not only aid in debugging complex issues but also help developers write more robust and secure C language programs. The next time you see a simple main function, consider the intricate execution world behind it.