Author: Han Lijie, Partner at Kaiteng Law Firm

Editor: Zheng Kejun, Su Yang

On March 17, Huada Jiutian announced that it plans to issue shares and pay cash to acquire 100% of the shares of Xinheng Semiconductor Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Ten days later, another EDA supplier, Gaolun Electronics, announced that it was planning to acquire Chengdu Ruicheng Chip Micro, joining the “merger war.” On April 11, Gaolun Electronics issued another announcement confirming the completion of its wholly-owned acquisition of Ruicheng Chip Micro, while simultaneously achieving full ownership of Nengwei Micro.EDA is the software tool used for designing and verifying chips, an indispensable foundational tool for chip design, often referred to as the “mother of chip design” in the industry. Overseas giants have generally grown through continuous mergers and acquisitions.Having worked in the industry for twenty years, I have witnessed the development of the domestic EDA industry and am acquainted with the founders of Huada Jiutian and Xinheng Semiconductor. Therefore, I intend to share my perspective as an eyewitness on this seemingly sudden but actually long-gestating “domestic EDA merger war.” First, let me share a conclusion for your reference—mergers and acquisitions are beneficial for the long-term healthy development of the industry and are a necessary path for the growth of giants, but this also means that a brutal elimination race has begun. It is important to note that large acquisition amounts are often accompanied by significant personnel adjustments and changes, more bluntly referred to as ‘layoffs.’

The Past and Present of China’s “Mother of Chips”

Huada Jiutian was established in 2009, which is not very early, but its core team and business have over thirty years of heritage in the EDA field.In 2008, the national major science and technology project was announced, which included chip design software. Huada Jiutian was born against this backdrop and was spun off from a state-owned enterprise to become independent.At that time, domestic semiconductor design companies generally used foreign tools, one important reason being that foreign companies had deeply penetrated universities since the last century, promoting their design tools among undergraduates.Faced with this starting point, Huada Jiutian can be said to have paved the way with great difficulty, establishing its position with simulation circuit tools, gradually developing into the domestic “number one.”The core team of Huada Jiutian developed China’s first EDA tool with independent intellectual property rights—the “Panda System” in the 1990s, evolving from an industry maverick to a leading figure with distinct local characteristics. The first ICCAD system with independent intellectual property rights in China won the National Science and Technology Progress Award in 1993. Source: Huaxi SecuritiesXinheng is different; its founding team had an international background from the start, focusing on challenging areas such as simulation and circuits. Its founders had previously worked for major companies like Motorola and Cadence and had also managed startups like Neolinear and Physware.This means that Huada Jiutian and Xinheng Semiconductor have very different development paths and environmental styles, but from the perspective of the industry chain, the merger of the two can be considered a strong complement.Xinheng’s tools in packaging, system design, and circuit boards can fill the gaps in Huada Jiutian, while Xinheng has just disclosed plans to go public on the Sci-Tech Innovation Board and has entered the counseling period. It is important to note that in the context of tightening IPOs, preparing for both an IPO and a merger is a wise move.Preparing for an IPO and a merger simultaneously is a common strategy in international capital markets, and the case of Xinheng and Huada Jiutian sends a signal—parallel tracks are also emerging in the domestic industry.If the market favors listed companies, it will inevitably emphasize going public, and mergers will naturally be overlooked. If going public is difficult and the merger valuation is reasonable, and the founding team is not obsessed with control, then mergers become the fast track.A typical semiconductor company generally has its equity divided among the founding team, investment institutions, and employees. In the case of a long and arduous IPO journey, investment institutions often hope to cash out or break even through mergers.In projects I have personally participated in, there have been 2-3 rounds of fundraising aimed at going public, but due to performance declines and delays in going public, the founders and investment institutions ultimately had to focus on overall sales.Compared to the development of overseas industries, there is still a gap—cases of acquisitions of Chinese semiconductor listed companies are rare, and the value of listed company shell resources is high, making them more likely to appear as acquirers. Direct acquisitions between listed companies in the U.S. occur frequently, such as AMD’s acquisition of Xilinx and Broadcom’s proposed acquisition of Qualcomm.

The first ICCAD system with independent intellectual property rights in China won the National Science and Technology Progress Award in 1993. Source: Huaxi SecuritiesXinheng is different; its founding team had an international background from the start, focusing on challenging areas such as simulation and circuits. Its founders had previously worked for major companies like Motorola and Cadence and had also managed startups like Neolinear and Physware.This means that Huada Jiutian and Xinheng Semiconductor have very different development paths and environmental styles, but from the perspective of the industry chain, the merger of the two can be considered a strong complement.Xinheng’s tools in packaging, system design, and circuit boards can fill the gaps in Huada Jiutian, while Xinheng has just disclosed plans to go public on the Sci-Tech Innovation Board and has entered the counseling period. It is important to note that in the context of tightening IPOs, preparing for both an IPO and a merger is a wise move.Preparing for an IPO and a merger simultaneously is a common strategy in international capital markets, and the case of Xinheng and Huada Jiutian sends a signal—parallel tracks are also emerging in the domestic industry.If the market favors listed companies, it will inevitably emphasize going public, and mergers will naturally be overlooked. If going public is difficult and the merger valuation is reasonable, and the founding team is not obsessed with control, then mergers become the fast track.A typical semiconductor company generally has its equity divided among the founding team, investment institutions, and employees. In the case of a long and arduous IPO journey, investment institutions often hope to cash out or break even through mergers.In projects I have personally participated in, there have been 2-3 rounds of fundraising aimed at going public, but due to performance declines and delays in going public, the founders and investment institutions ultimately had to focus on overall sales.Compared to the development of overseas industries, there is still a gap—cases of acquisitions of Chinese semiconductor listed companies are rare, and the value of listed company shell resources is high, making them more likely to appear as acquirers. Direct acquisitions between listed companies in the U.S. occur frequently, such as AMD’s acquisition of Xilinx and Broadcom’s proposed acquisition of Qualcomm.

EDA: Big Fish Eat Small Fish, No Snake Swallowing Elephant

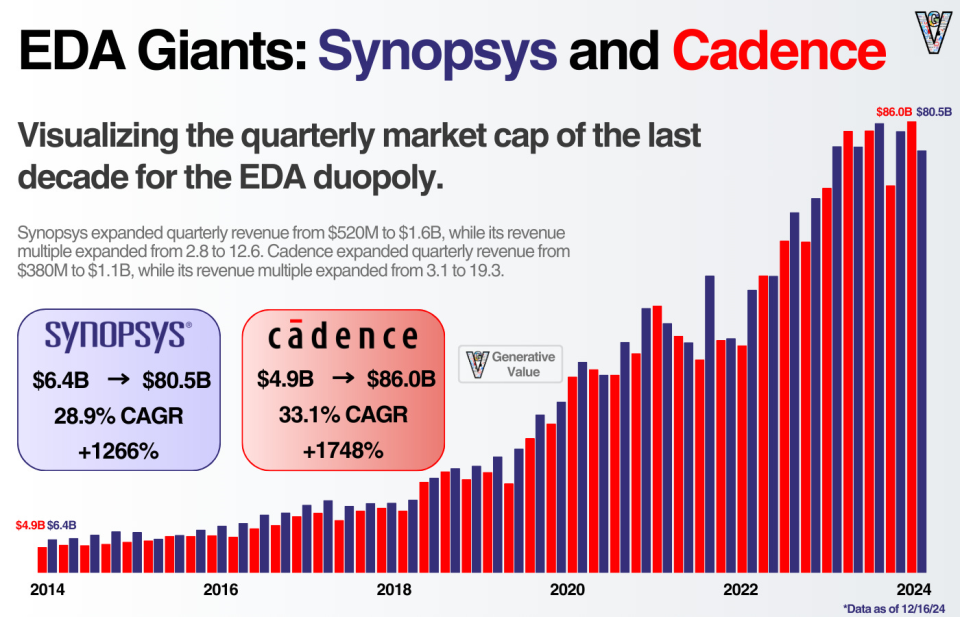

Currently, there are only three domestic EDA companies listed on the A-share market: Huada Jiutian, Gaolun Electronics, and Guangli Microelectronics.There are over 80 unlisted EDA companies, each with varying survival conditions—some are strong (like Xinheng and Hejian Gongruan), while others have benchmark products in several segments, such as Hongxin Micro, which has received support from the National Big Fund, and several others that have received significant capital attention in recent years and can still operate calmly in the current environment.From what I understand, most domestic EDA companies have revenues just over 10 million, facing high operational costs, especially labor costs. To put it bluntly, half of these companies are likely close to the critical point of cash flow breakage.In contrast, the situations of the already listed Gaolun Electronics and Huada Jiutian are worlds apart; both are well-versed in the art of mergers and acquisitions and have been making significant strategic investments and acquisitions since going public.In 2023, Gaolun Electronics acquired Fuzhou Chip Intelligence. In 2024, Huada Jiutian acquired Akas Holdings. These two cases occurred in the past two years, but the transaction logic is different.Akas’s verification tools have a good reputation in the market, supported by institutions like Hubble and Shanghai Kechuang, and Huada Jiutian’s acquisition of Akas was valued at approximately 300 million RMB, effectively supplementing its product line. The valuation of Fuzhou Chip Intelligence is unclear, and the estimated acquisition price is not high; according to Gaolun Electronics’ announcement, it has recognized goodwill impairment losses from this acquisition.There is also an interesting phenomenon here: companies that have initiated IPOs or even withdrawn from them, having undergone the baptism of the capital market, are more favored in subsequent mergers.The semiconductor industry is highly concentrated, technology-intensive, and capital-intensive, with a winner-takes-all dynamic. Its industrial development history is also a history of mergers and acquisitions, particularly evident in the EDA field—globally, there are only three large companies: Synopsys, Cadence, and Siemens, all of which have emerged after experiencing dozens or even hundreds of mergers. Changes in market capitalization of Synopsys and Cadence over the past 10 years. Source: GVMergers and acquisitions are the underlying color of EDA tools and the semiconductor industry; the limited market size is also the underlying logic driving company mergers.According to SNS Insider, the global EDA market was approximately $14.6 billion in 2023, projected to grow to $32.75 billion by 2032, with a compound annual growth rate of about 9.35%. In contrast, WICA estimates the total semiconductor market size in 2023 to be around $530 billion, highlighting the scale of the EDA market.From our observed data, the Chinese EDA market is approximately 10 billion RMB, covering numerous subfields such as front-end, back-end, and analog, with several to dozens of companies competing in each field. According to industry norms, the ultimate limit for each subfield is already three to five companies.Additionally, the Chinese market is currently in a period of retreat for chip startups, with some design companies established in 2019 already struggling, while those that have successfully scaled are also controlling costs due to cyclical impacts. This contraction in the downstream market will also transmit to upstream suppliers, accelerating the mergers of EDA software.The global market size itself is limited, and customers are also shrinking due to cyclical impacts. Even if the Chinese market is large, it cannot sustain so many companies in the long term, resulting in a survival of the fittest scenario.All of the above are objective factors driving mergers, while EDA companies also have subjective needs to participate in international competition.EDA companies are positioned upstream in the semiconductor industry, with customers spanning the entire semiconductor supply chain, from upstream design companies like NVIDIA and Apple to downstream manufacturers like TSMC, all requiring specialized products. This self-research across the entire industry chain poses a significant challenge for leading companies.

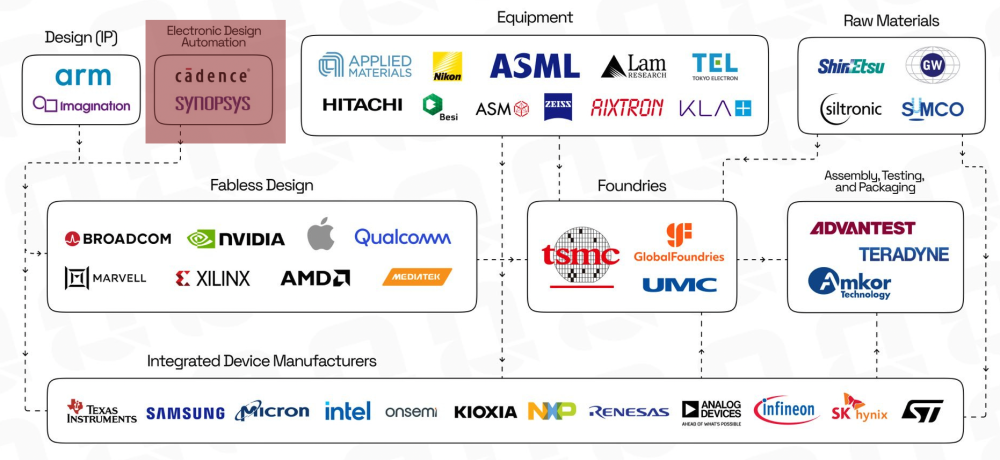

Changes in market capitalization of Synopsys and Cadence over the past 10 years. Source: GVMergers and acquisitions are the underlying color of EDA tools and the semiconductor industry; the limited market size is also the underlying logic driving company mergers.According to SNS Insider, the global EDA market was approximately $14.6 billion in 2023, projected to grow to $32.75 billion by 2032, with a compound annual growth rate of about 9.35%. In contrast, WICA estimates the total semiconductor market size in 2023 to be around $530 billion, highlighting the scale of the EDA market.From our observed data, the Chinese EDA market is approximately 10 billion RMB, covering numerous subfields such as front-end, back-end, and analog, with several to dozens of companies competing in each field. According to industry norms, the ultimate limit for each subfield is already three to five companies.Additionally, the Chinese market is currently in a period of retreat for chip startups, with some design companies established in 2019 already struggling, while those that have successfully scaled are also controlling costs due to cyclical impacts. This contraction in the downstream market will also transmit to upstream suppliers, accelerating the mergers of EDA software.The global market size itself is limited, and customers are also shrinking due to cyclical impacts. Even if the Chinese market is large, it cannot sustain so many companies in the long term, resulting in a survival of the fittest scenario.All of the above are objective factors driving mergers, while EDA companies also have subjective needs to participate in international competition.EDA companies are positioned upstream in the semiconductor industry, with customers spanning the entire semiconductor supply chain, from upstream design companies like NVIDIA and Apple to downstream manufacturers like TSMC, all requiring specialized products. This self-research across the entire industry chain poses a significant challenge for leading companies. EDA’s distribution in the semiconductor industry chain, source: Quartr AppIf they want to compete for customers with European and American giants, mergers are the only shortcut for expansion, which is also why I mentioned earlier that the brutal elimination race has begun.The acceleration of domestic EDA mergers also has a special external factor—U.S. technology restrictions.Currently, the most advanced logic chips have reached 2-3 nanometer processes, but related EDA tools are embargoed for these process nodes in the Chinese market. This means that Chinese chip design companies can only rely on domestic tools for developing 2-3 nanometer processes. However, design requires a complete set of tools, and domestic EDA companies are limited by their own categories and cannot provide a complete solution at the 2-3 nanometer node. Only horizontal mergers and expansions can quickly obtain a complete product line and seize the high-end, advanced process market.Objectively speaking, the three listed Chinese EDA companies have all developed in the cracks of multinational giants, all accelerating mergers, but none yet possess the capability to provide a full chain of EDA tools, a fact we must recognize.In other words, Chinese chip design companies still have a dependency on overseas EDA giants, and relying on foreign products inevitably leads to the topic of “choke points,” necessitating vigilance against intellectual property risks.Foreign EDA tools are expensive, and those design companies that have successfully raised funds must often spend tens of millions to purchase foreign EDA tools right at the start of sales. Smaller companies with less funding may resort to using pirated products, which may not attract excessive attention if they do not go public, but if they initiate an IPO, foreign EDA giants will come to enforce their rights.In recent years, I have had several chip design company clients successfully go public, and most of them received letters from overseas EDA companies before going public, demanding payment for usage fees. Some indeed used pirated versions and paid up; others used legitimate versions but exceeded the licensed scope, for example, obtaining a license for use on five machines but actually using it on ten. This kind of pre-IPO demand for payment is quite common, and Chinese companies ultimately end up paying.

EDA’s distribution in the semiconductor industry chain, source: Quartr AppIf they want to compete for customers with European and American giants, mergers are the only shortcut for expansion, which is also why I mentioned earlier that the brutal elimination race has begun.The acceleration of domestic EDA mergers also has a special external factor—U.S. technology restrictions.Currently, the most advanced logic chips have reached 2-3 nanometer processes, but related EDA tools are embargoed for these process nodes in the Chinese market. This means that Chinese chip design companies can only rely on domestic tools for developing 2-3 nanometer processes. However, design requires a complete set of tools, and domestic EDA companies are limited by their own categories and cannot provide a complete solution at the 2-3 nanometer node. Only horizontal mergers and expansions can quickly obtain a complete product line and seize the high-end, advanced process market.Objectively speaking, the three listed Chinese EDA companies have all developed in the cracks of multinational giants, all accelerating mergers, but none yet possess the capability to provide a full chain of EDA tools, a fact we must recognize.In other words, Chinese chip design companies still have a dependency on overseas EDA giants, and relying on foreign products inevitably leads to the topic of “choke points,” necessitating vigilance against intellectual property risks.Foreign EDA tools are expensive, and those design companies that have successfully raised funds must often spend tens of millions to purchase foreign EDA tools right at the start of sales. Smaller companies with less funding may resort to using pirated products, which may not attract excessive attention if they do not go public, but if they initiate an IPO, foreign EDA giants will come to enforce their rights.In recent years, I have had several chip design company clients successfully go public, and most of them received letters from overseas EDA companies before going public, demanding payment for usage fees. Some indeed used pirated versions and paid up; others used legitimate versions but exceeded the licensed scope, for example, obtaining a license for use on five machines but actually using it on ten. This kind of pre-IPO demand for payment is quite common, and Chinese companies ultimately end up paying.

Overseas Giants’ Merger “Textbook”

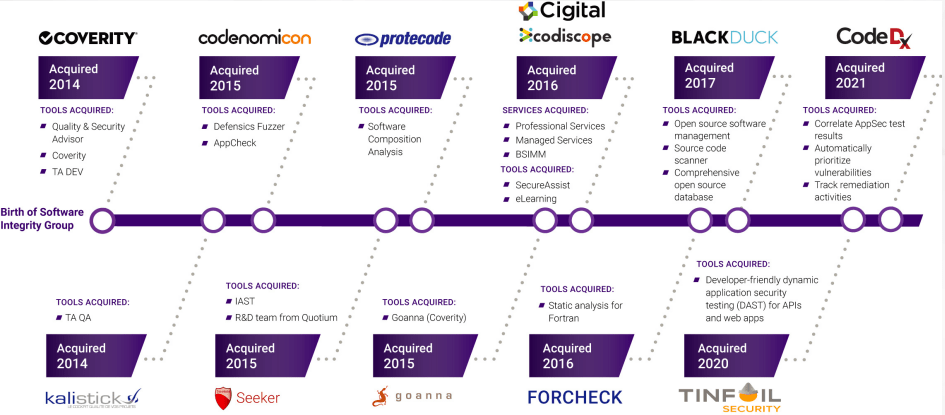

The growth history of the three international EDA giants is essentially a history of mergers.Since its establishment in 1986, Synopsys has initiated dozens of mergers, continuously expanding its product and business scale; mergers have been ingrained in its DNA. It can be said that the overseas EDA industry has developed alongside the evolution of the semiconductor industry for decades and has not stopped its merger activities to this day.On January 9, 2024, Cadence announced the completion of its acquisition of Invecas, Inc. In October of the same year, Siemens acquired industrial software company Altair Engineering.On January 16 of this year, Synopsys announced its acquisition of industrial software company ANSYS for $35 billion, whose simulation software is also used in automotive and aerospace fields—this means that after years of fierce competition with Cadence and others, Synopsys is beginning to extend its business reach beyond the $10 billion EDA market. Synopsys’ acquisition cases over the past decade, data as of 2020. Source: SeekAlphaThe merger and expansion of EDA giants serves as a rich textbook for their domestic counterparts.Over the past 70 years, the global semiconductor industry has gone through several cycles, with industry giants achieving continuous growth through mergers, ultimately successfully navigating through intense competition.By the 21st century, the semiconductor industry entered a mature phase, with rapid technological advancements, globalized supply chains, and capital-intensive investments, making winner-takes-all the norm in the industry—ASML dominates the lithography machine market, Intel and AMD are in a duopoly for microprocessors, and Samsung, Hynix, and Micron dominate the memory market.In the early 2000s, due to declining capital returns, venture capital significantly decreased, leading to fewer semiconductor company IPOs and accelerating the pace of cross-border mergers.After 2011, the wave of mergers in the semiconductor industry surged, roughly divided into two phases: 2011-2017 (the first phase) and 2018 to the present (the second phase).The first phase was stimulated by factors such as smartphones and automotive applications represented by Apple, leading to continuous growth in semiconductor company revenues and profits. By around 2015, due to technological maturity, market saturation, and slowing company growth, rising costs, and compressed profits, industry giants initiated an unprecedented wave of mergers, with NXP acquiring Freescale and Broadcom announcing plans to acquire Qualcomm.The second phase, marked by the U.S.-China trade dispute, saw a distorted integrated circuit supply chain and a shortage of chip products. In a time of great contention, not advancing means retreating, prompting industry giants to launch massive mergers to increase market share and solidify their positions—NVIDIA announced its acquisition of ARM, completed the acquisition of Mellanox, and AMD completed its acquisition of Xilinx, accelerating industry concentration once again.However, the acquisitions by giants have not been without obstacles.AMD’s acquisition of Xilinx and NXP’s acquisition of Freescale faced no difficulties from regulatory bodies and were successfully completed, but Broadcom’s acquisition of Qualcomm and NVIDIA’s acquisition of ARM both faced regulatory scrutiny and ultimately failed.With the rise of artificial intelligence and humanoid robots, the next round of industry consolidation has already begun, with OpenAI emerging, and NVIDIA and TSMC becoming the kings of the semiconductor industry, making industry consolidation and asset divestiture a natural occurrence.Just recently, Intel sold off 51% of its stake in the Altera business it acquired ten years ago at a 50% discount, indicating that even giants like Intel must divest assets.The tides of time wash away those new forces that cannot evolve into giants, marking them as the old forces of the next era.

Synopsys’ acquisition cases over the past decade, data as of 2020. Source: SeekAlphaThe merger and expansion of EDA giants serves as a rich textbook for their domestic counterparts.Over the past 70 years, the global semiconductor industry has gone through several cycles, with industry giants achieving continuous growth through mergers, ultimately successfully navigating through intense competition.By the 21st century, the semiconductor industry entered a mature phase, with rapid technological advancements, globalized supply chains, and capital-intensive investments, making winner-takes-all the norm in the industry—ASML dominates the lithography machine market, Intel and AMD are in a duopoly for microprocessors, and Samsung, Hynix, and Micron dominate the memory market.In the early 2000s, due to declining capital returns, venture capital significantly decreased, leading to fewer semiconductor company IPOs and accelerating the pace of cross-border mergers.After 2011, the wave of mergers in the semiconductor industry surged, roughly divided into two phases: 2011-2017 (the first phase) and 2018 to the present (the second phase).The first phase was stimulated by factors such as smartphones and automotive applications represented by Apple, leading to continuous growth in semiconductor company revenues and profits. By around 2015, due to technological maturity, market saturation, and slowing company growth, rising costs, and compressed profits, industry giants initiated an unprecedented wave of mergers, with NXP acquiring Freescale and Broadcom announcing plans to acquire Qualcomm.The second phase, marked by the U.S.-China trade dispute, saw a distorted integrated circuit supply chain and a shortage of chip products. In a time of great contention, not advancing means retreating, prompting industry giants to launch massive mergers to increase market share and solidify their positions—NVIDIA announced its acquisition of ARM, completed the acquisition of Mellanox, and AMD completed its acquisition of Xilinx, accelerating industry concentration once again.However, the acquisitions by giants have not been without obstacles.AMD’s acquisition of Xilinx and NXP’s acquisition of Freescale faced no difficulties from regulatory bodies and were successfully completed, but Broadcom’s acquisition of Qualcomm and NVIDIA’s acquisition of ARM both faced regulatory scrutiny and ultimately failed.With the rise of artificial intelligence and humanoid robots, the next round of industry consolidation has already begun, with OpenAI emerging, and NVIDIA and TSMC becoming the kings of the semiconductor industry, making industry consolidation and asset divestiture a natural occurrence.Just recently, Intel sold off 51% of its stake in the Altera business it acquired ten years ago at a 50% discount, indicating that even giants like Intel must divest assets.The tides of time wash away those new forces that cannot evolve into giants, marking them as the old forces of the next era.

The Capital Game of Domestic Chips

Since 2017, U.S.-China economic and trade frictions have focused on high-tech fields, with the U.S. and Europe imposing numerous restrictions on overseas acquisitions by Chinese semiconductor companies. During this phase, the number of acquisitions by Chinese companies of overseas semiconductor projects has sharply declined. In contrast, domestically, due to the large market size and scattered company distribution, mergers have been on the rise.Many reasons have been mentioned earlier, such as the decline of the entrepreneurial boom and U.S.-China technological competition, which have led to declining valuations for related companies, with some facing financing difficulties, while capital remains cautious. These entrepreneurial companies are all potential targets for acquisition.On the other hand, leading companies have generally gone public successfully and hold large amounts of cash, making mergers a quick path to complete supply chain capabilities.There are also some special cases, such as some traditional companies hoping to achieve business transformation through cross-border acquisitions of semiconductor assets.In summary, the most common type of domestic semiconductor merger project is led by listed companies acquiring unlisted companies, with occasional mergers between unlisted companies, but the latter are rarely successful due to valuation and funding source constraints.Regarding the starting point of this round of mergers, the industry generally believes it began at the end of 2022, with the logic of judgment being the decline of investment enthusiasm, the downward cycle of the industry, and increasing competition. However, in reality, many companies remained resilient in 2023, with only sporadic mergers; many of those advocating for mergers during this phase were financial institutions—facing exits after three years of investment.For companies, mergers can reduce competitors, and equity restructuring can provide exit opportunities for investors.On the surface, companies appear eager, but there is a lack of consensus on valuations, and reaching agreement on post-merger management rights is also challenging. Many companies have been dragged down by time, and some have reached a point where they will wither if not acquired.During this phase, it has become evident that many chip companies are being deregistered, and even industry giants like OPPO have shut down their in-house chip development business for various reasons.On the news front, Weilai and Xiaopeng have successfully taped out their self-developed 5nm automotive chips, and Xiaomi is rumored to be releasing its self-developed Xuanjie SoC soon, which can be seen as some positive developments in chip design during the winter of domestic chips.Of course, we must also recognize the reasons behind these good news—the current competition is focused on AI chips.By 2024, a large number of mergers led by listed companies emerged, totaling over 30, with some projects successfully completed and others ending unhappily, with the most transactions occurring in analog chips, such as Naxin Micro’s acquisition of Maigen.After the release of the “Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the Mergers and Acquisitions Market for Listed Companies,” semiconductor merger transactions have significantly increased, with about 20 occurring in the first quarter of 2025.Although the number of publicly announced merger cases is gradually increasing, the success rate is much lower compared to overseas mergers, with more than half ultimately failing to close. Commercial factors dominate this process, which is quite different from the overseas situation—mergers in the overseas semiconductor field, excluding those blocked by regulatory scrutiny, such as the U.S. government’s antitrust and national security reviews that halted Broadcom’s acquisition of Qualcomm, are generally completed smoothly.In contrast, the factors affecting mergers in the Chinese semiconductor industry are more concentrated on acquisition valuation discrepancies, product cycles matching with buyers, and post-acquisition integration challenges.As mentioned earlier, the investment boom from 2020 to 2021 drove up company valuations, but after several years of sedimentation, some companies have reached a critical point of survival. In this environment, both founding teams and institutional investors have their interests in mind regarding acquisition valuations, especially since the costs for shareholders of different investment companies vary.Therefore, during the acquisition process, buyers often adopt a wait-and-see attitude, and as long as no payment has been made, they can withdraw at any time, resulting in a low success rate.With so many differing opinions, in some merger projects, the valuations given by buyers to different shareholders vary, and some shareholders may even need to sell their shares at a discount. This process can also include some special cases—some target companies may be in a loss state, and when a listed company acquires a loss-making company, it will attract significant attention from securities regulatory agencies, which can create obstacles.In terms of the compatibility of the product cycle of the acquisition target with the buyer, the current situation is not optimistic. Some companies face issues such as customer loss, market shrinkage, and product aging, which will be closely scrutinized by buyers in the merger market. In several projects I have operated, some have shifted from acquiring 100% equity to small equity investments, while others have simply abandoned the transaction.How to integrate companies post-acquisition is also a key factor affecting mergers—whether all parties can generate good chemistry.In other words, mergers are not the end; integration truly determines success or failure. Management teams, business departments, factory equipment, human resources, customer resources, and sales channels all need to be reasonably integrated, with some leaders from the acquired company remaining and others taking their money and leaving.From my personal experience, while there are successful merger cases, they are not numerous; extremely failed merger cases are also relatively few, with most yielding mediocre results.After transactions are completed, some projects may seem successful, but the teams and technologies are difficult to integrate, or the increase in revenue from the merger results in lower profit margins. In my experience, achieving success in mergers is only about one in ten or twelve.Among various merger transactions, the success rate of acquisitions involving asset divestitures is relatively high. Divestiture is a very common restructuring method for semiconductor companies—acquiring new business segments with one hand while divesting non-core businesses with the other to enhance product competitiveness and profit margins is a decades-old strategy for international companies.As mentioned earlier, Intel divested its Altera business and sold 51% of its shares to Silver Lake Partners. This shows that even strong companies like Intel have reached a point where they must divest assets.Most domestic chip giants are keen on expansion, with few actively divesting; an exception is Wentech, a supplier in Apple’s supply chain.In January 2025, Wentech successively transferred its ODM business to Luxshare Precision, with market speculation suggesting that the driving force behind this is the common major client, Apple. Based on my experience, transactions recognized by Apple are likely to succeed due to market endorsement. This transaction is a typical asset divestiture deal, where the seller exits the relevant field and the buyer takes over.After divesting its ODM business, Wentech began to develop its semiconductor business based on the acquired Nexperia, which is a case of acquiring with one hand and divesting with the other.Just this past March, I also completed a semiconductor divestiture project, where an international semiconductor company readily sold its production lines in mainland China and Europe to a Chinese company, exiting the production of low-margin devices. The Chinese company seized the opportunity to gain capacity and technology, entering some high-end international markets. Of course, this asset package was acquired by this international company at a high price ten years ago, and it has lost 90% over the past decade, reflecting the brutal side of mergers.These examples are meant to convey an insight—Chinese companies acquiring semiconductor assets divested by European and American companies is a shortcut to accelerated development.Looking back ten years, opportunities like Wentech’s acquisition of Nexperia were more common; at that time, semiconductor mergers primarily sought overseas targets, achieving a one-step solution through transactions. This model has vanished with the changes in international circumstances.Looking back five years, the semiconductor startup scene was thriving, with everyone vying to go public, and company valuations were extraordinarily high, making mergers difficult to implement, as valuations could only be digested through capital markets.Currently, there are already hundreds of semiconductor listed companies, with leaders in various subfields, while many startup companies have seen significant declines in valuations, and investors’ patience is limited, leading founding teams to adopt more flexible attitudes. At the same time, policies actively encourage mergers, and some financial institutions are willing to provide financing support for mergers up to 80% of the transaction amount, an unprecedented situation. All signs indicate that a grand era of mergers in the Chinese semiconductor industry has arrived.

Recommended Reading: Chip Matters Series

China’s “Investment Godfather” All in Intel

China’s “Investment Godfather” All in Intel DeepSeek Breaks NVIDIA’s “Computing Power Hegemony”

DeepSeek Breaks NVIDIA’s “Computing Power Hegemony” “30,000 Cards” from DeepSeek Brings 500 Billion Red Envelopes

“30,000 Cards” from DeepSeek Brings 500 Billion Red Envelopes