When building an agent system, the performance of a single agent always has its bottlenecks. When the complexity of tasks crosses a certain threshold, the “Multi-Agents” architecture becomes a necessary path.

Claude has recently made groundbreaking attempts in the field of multi-agent research systems, fully disclosing the architectural design challenges, prompt optimization strategies, and practical techniques encountered from prototype to production, which has greatly inspired me personally. Whether you are just entering the field of agents or wish to gain a deeper understanding of multi-agent collaboration mechanisms, this article is worth reading repeatedly. I recommend that you carefully understand each principle and gradually validate it in practice.

How We Built the Multi-Agent Research System

Claude now possesses research capabilities, able to automatically complete complex tasks across networks, Google Workspace, and various integrated tools.

The process of bringing this multi-agent system from prototype to production environment has provided us with many key experiences regarding system architecture, tool design, and prompt engineering.

A multi-agent system is one where multiple agents (LLMs can autonomously cycle through tools) work collaboratively. In our Research function, the core is a leading agent that orchestrates the research process, formulates plans based on user inquiries, and utilizes tools to create multiple parallel agents (sub-agents) that simultaneously conduct information retrieval. This kind of multi-agent collaboration also introduces new challenges, such as coordination between agents, result evaluation, and system reliability.

This article will break down the principles that have been validated in our practice, hoping to provide references for you to build your own multi-agent system.

Advantages of Multi-Agent Systems

Research work is inherently open-ended and it is difficult to preset a “necessary path” in advance. You cannot hard-code a fixed process for exploring complex topics because the research process in the real world is dynamic and path-dependent. When people conduct research, they are constantly adjusting their routes based on discoveries and tracking newly emerging clues.

Because of this unpredictability, AI agents exhibit a natural adaptability in research scenarios. Research work requires flexibility to pivot and the ability to uncover unexpected connections during exploration. Agents need to operate autonomously for extended periods, deciding subsequent exploration directions based on periodic discoveries. Linear, one-time processes simply cannot handle such tasks.

Essentially, the core of retrieval is “compression”—extracting insights from vast amounts of information. Multi-sub-agents act like efficient compression engines, exploring different directions in their respective context windows in parallel, and then refining and summarizing the most critical content for the main agent. Each sub-agent also benefits from having “clear division of labor”—each using different tools, prompts, and exploration paths, reducing path dependence and enhancing independence and global coverage.

Once the capabilities of agents reach a certain threshold, multi-agent systems become the necessary path for scaling capabilities. For example, over the past hundred thousand years, individual human intelligence may have improved only slightly, but the collective intelligence and collaborative ability of human society have experienced exponential leaps in the information age.Similarly, no matter how powerful a single agent is, it has a ceiling, while the collaboration of multiple agents can amplify system capabilities several times.

Our internal evaluations indicate that multi-agent research systems perform particularly well in tasks requiring breadth-first, parallel exploration. For instance, using Claude Opus 4 as the main agent and Claude Sonnet 4 as sub-agents, the performance in internal research evaluations was90.2% higher than that of the single agent Claude Opus 4. For example, when tasked with “listing all board members of companies in the S&P 500 Information Technology sector,” the multi-agent system can automatically decompose the task, allowing sub-agents to each find answers, while a single agent’s linear search often fails to find everything or is extremely inefficient.

The principle of multi-agent systems is actually quite simple: it can mobilize enough token resources to truly solve the problem. In our analysis, the 95% performance difference in the BrowseComp (https://openai.com/index/browsecomp/) test for locating rare information can be explained by three main factors: token usage (which itself explains 80% of the difference), the number of tool calls, and model capability. In other words, allowing different agents to reason in parallel in independent contexts essentially translates the scale of tokens into system capabilities. The latest Claude model can significantly improve token usage efficiency; just from the upgrade of Sonnet 4, the effect is even better than doubling the token limit for Sonnet 3.7. For large-scale tasks that exceed the context window of a single agent, the multi-agent architecture inherently has advantages in horizontal scaling.

Of course, there are also drawbacks:the token consumption of multi-agent systems is very fast. In our data, single-agent tasks use 4 times more tokens than chat, while multi-agent systems use 15 times more tokens than regular chat. To make such a high-consumption system economically viable, it is essential to lock in those “high-value” tasks; otherwise, the cost-effectiveness is too low.

Additionally, in some scenarios,such as when all agents need to share the same context and there are many dependencies between agents—multi-agent systems are currently not suitable. For example, most code generation tasks actually have limited parallelism, and LLM agents currently have limited capabilities in “real-time coordination and division of labor.” We have found that multi-agents perform best in scenarios that require extreme parallelism, where the information volume far exceeds a single context window and where there are high demands for multi-tool integration.

Overview of the Research System Architecture

Our Research system adopts a multi-agent architecture, with the core being a “coordinator-executor” model: the main agent (orchestrator) is responsible for overall process coordination, while specific tasks are assigned to parallel running dedicated sub-agents (workers).

The multi-agent architecture operates as follows: After a user inquiry, the main agent analyzes the question, formulates a strategy, and then creates multiple specialized sub-agents to simultaneously and in parallel search for answers in different directions. In the case shown in the image above, the sub-agents each use retrieval tools to gather information (such as a list of AI agent companies in 2025), and then return the results to the main agent, which ultimately compiles the answers.

Traditional retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is generally “static retrieval,” meaning that it pre-selects the text blocks most relevant to the question and then directly uses these blocks to generate answers. In contrast, our architecture employs “multi-step dynamic retrieval”: agents dynamically adjust strategies based on periodic discoveries, actively searching for and analyzing information multiple times to ultimately output high-quality answers.

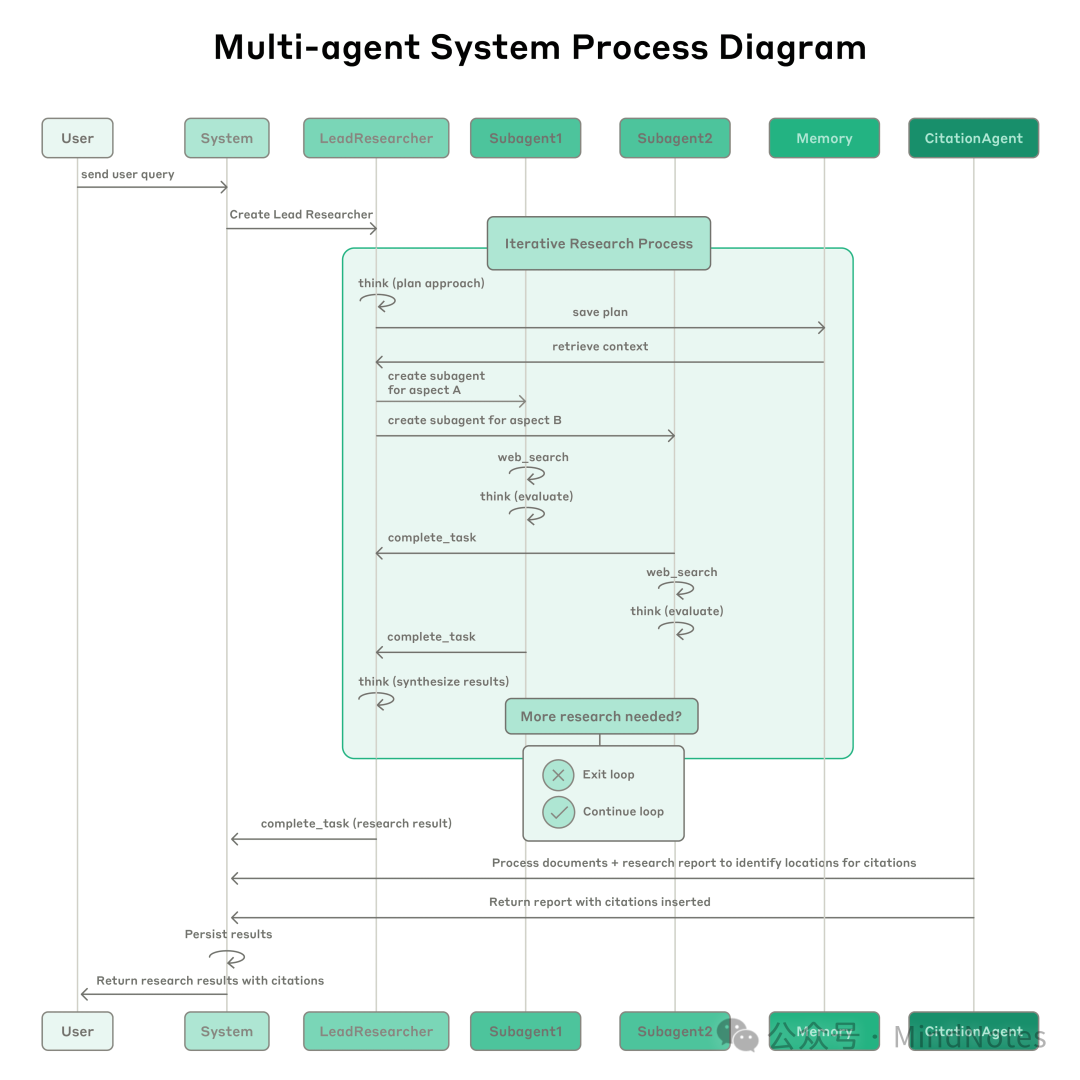

Flowchart of the Multi-Agent Research System

When a user submits a question, the system generates a LeadResearcher (main researcher agent), which enters an iterative research process. The LeadResearcher first considers how to decompose the question and stores the plan in Memory to retain context—because once the context exceeds 200,000 tokens, the content will be truncated, so the plan must be archived.

Next, it creates dedicated sub-agents (generally starting with two, which can dynamically expand) based on task decomposition, each responsible for different research tasks. Each sub-agent independently conducts web searches, evaluates tool results using interleaved thinking, and returns findings to the main agent.

The LeadResearcher synthesizes all results and determines whether further research is needed—if necessary, it can generate more sub-agents or adjust strategies. Once the information gathering is complete, the system hands all findings over to the CitationAgent, which handles specific source citations for conclusions in reports and documents, ensuring that all assertions can be traced back to their sources. The final research results (including complete citations) are then returned to the user.

Prompt Engineering and Evaluation for Research Agents

Multi-agent systems differ fundamentally from single-agent systems,with the most significant difference being the sharp increase in “coordination complexity.” Early agents often made mistakes such as generating 50 sub-agents for simple questions, searching the entire web for resources that do not exist, and frequently interrupting each other. The behavior of each agent is controlled by prompts, so prompt engineering is our most critical tuning lever.

Here are eight principles we have summarized regarding agent prompt engineering:

- 1. Think from the agent’s perspective. To tune prompts effectively, one must understand the decision logic from the agent’s perspective. We specifically use Console to restore the system’s prompts and tools, gradually observing how agents operate. This can quickly expose issues: for example, retrieving continuously despite having sufficient results, querying lengthy and ineffective information, or using the wrong tools. Only by accurately grasping the agent’s thinking patterns can we efficiently identify and optimize core bottlenecks.

- 2. Teach the main agent how to delegate tasks. In our system, the main agent must decompose questions into sub-tasks and communicate them clearly. Each sub-agent must receive a clear goal, output format, recommended tools and data sources, and well-defined boundaries. Otherwise, agents may duplicate efforts, overlook core elements, or act independently. Initially, we only allowed the main agent to give brief instructions, such as “research semiconductor shortages,” but found that such vague expressions often led multiple sub-agents to search in overlapping directions, resulting in failed collaboration. For instance, some might check the 2021 automotive chip crisis while others look into the 2025 supply chain, failing to form a cohesive effort.

- 3. The complexity of tasks should be proportional to the number of agents. Agents find it difficult to judge task volume on their own, so we embed the “task-resource matching” rule into prompts. Simple fact-checking requires 1 agent and 3-10 tool calls, direct comparison questions need 2-4 sub-agents, each with 10-15 tool calls, while complex research may require 10+ sub-agents with subdivided responsibilities. This clear rule prevents resource mismatches and avoids resource waste on low-complexity tasks.

- 4. The design and selection of tools are crucial. The interface between agents and tools is as important as the interaction between humans and computers. Choosing the right tools is not only efficient but sometimes the only way forward. For example, searching for a piece of information that only exists in Slack context is bound to be futile. The MCP server (Model Context Protocol) empowers models to access external tools, further complicating the issue—agents encounter numerous new tools with varying descriptive styles. We have summarized explicit heuristics for agents: for instance, browse all available tools first, tool selection should align with user intent, broadly explore using web searches, and specialized tools are preferred over general ones. If tool descriptions are unclear, agents can easily go off track, so each tool must have “clear responsibilities and descriptions.”

- 5. Allow agents to self-evolve. We have found that the Claude 4 model itself is an excellent prompt engineer. If you provide it with failure cases and original prompts, it can analyze the reasons and suggest improvements. We even created a “tool testing agent” that repeatedly tests MCP tools and revises tool descriptions until most misconceptions are eliminated. This process can reduce the task completion time for subsequent agents using that tool by 40%, significantly lowering the error rate.

- 6. Start broad and then focus. Retrieval strategies should resemble those of human experts: first scan the entire landscape, then delve into details. Agents often make the mistake of “going too detailed too soon,” resulting in incomplete searches. We particularly emphasize in prompts to start with divergent questions, review available information, and then gradually narrow the focus.

- 7. Guide the thinking process. Expanding the thinking model allows Claude to output more “visible thinking,” like a personal notebook. The main agent uses it to plan, considering which tools to use, how many sub-tasks to divide, and how to break down responsibilities. Our tests have shown that enabling expanded thinking significantly improves adherence to instructions, reasoning ability, and execution efficiency. Sub-agents also adopt an “interleaved thinking method,” planning before searching, reflecting on result quality after each search, identifying gaps, and adjusting the next query. This way, when faced with complex tasks, sub-agents can continuously adapt and optimize their strategies.

- 8. Parallel tool calls greatly enhance efficiency and performance. Complex research tasks inherently require multi-source concurrent checks. Our early agents used serial retrieval, which was extremely slow. Later, we implemented two types of parallel acceleration: first, the main agent generates 3-5 sub-agents to search concurrently, and second, each sub-agent can also concurrently call more than 3 tools. As a result, the research time for complex problems was reduced by 90%, significantly enhancing information coverage and the depth of conclusions.

Our prompt engineering focuses more on “instilling methodology” rather than mechanical stipulations. We draw on strategies from excellent human researchers, such as decomposing problems, assessing information source quality, dynamically adjusting search paths, and adeptly switching between “in-depth digging” and “broad coverage,” and incorporate these experiences into prompts. At the same time, we set clear “guardrails” in advance for negative behaviors (such as infinite recursion, spinning, etc.). The entire development process maintains a high-frequency iteration of “observe-optimize-test.”

Effective Evaluation of Agent Systems

Building reliable AI applications relies on a quality evaluation system, and multi-agent systems are no exception. However, the evaluation of multi-agents is much more challenging than traditional single agents. Previous evaluations assumed that AI would always follow the same path: given input X, the system should sequentially complete Y steps to output Z. But multi-agents do not work this way; even with identical inputs, they may take entirely different yet equally correct paths. Some agents may check three clues, while others check ten, using different tools, yet still achieve the same goal. Therefore, we cannot simply judge by “whether the preset process was strictly followed” but must focus on “whether the goal was achieved and whether the process was reasonable.”

Evaluation should be initiated early and conducted with small samples first. In the early stages of agent development, any adjustments often lead to significant improvements (for example, fine-tuning prompts can increase success rates from 30% to 80%). At this point, testing with about 20 representative questions from real scenarios can keenly capture changes. Many teams mistakenly believe that evaluation should wait until hundreds or thousands of use cases are created; in fact, the earlier “small sample rapid iteration” is more effective.

Using LLMs as evaluators can efficiently scale evaluation. Research outputs are mostly open-ended text, making it impossible to automatically score them with programs. LLMs are a natural choice for grading. We designed scoring criteria (fact accuracy, citation accuracy, content completeness, information source quality, tool usage efficiency, etc.) and used LLMs to evaluate each item. Initially, we tried multi-modal evaluations but found that “single LLM, single output, 0-1 scoring + pass/fail judgment” was the most stable and consistent with human evaluations. As long as the test questions have standard answers, such as “list the top three pharmaceutical companies by R&D investment,” LLMs can score efficiently. This way, we can quickly batch evaluate hundreds of outputs using LLMs.

Human testing can capture issues missed by automation. Human testers can identify many edge cases, such as agent hallucinations under rare inquiries, system failures, and subtle biases in information source selection. We discovered early on that agents tended to use high-ranking but less authoritative websites, avoiding academic PDFs or quality blogs. Thus, we added a “information source quality” rule in the prompts, which resolved the issue. Even with automated evaluations, human validation remains indispensable.

Multi-agent systems can also exhibit “emergent behavior, which is not pre-programmed but automatically formed through the collaborative process. For example, fine-tuning the main agent can significantly alter the decision logic of sub-agents. To successfully implement, one must not only look at the behavior of individual agents but also understand the entire interaction pattern. Therefore,good prompts are not “rigid rules” but rather a “collaborative framework”—clearly delineating roles, collaboration methods, resource allocation, etc. Achieving this requires rigorous prompt engineering, reasonable tool design, scientific heuristics, full observability, and high-frequency feedback iteration. You can check our open-source prompts in the Anthropic Cookbook.

Production Reliability and Engineering Challenges

In traditional software, a bug may cause a function to fail, performance to degrade, or the system to crash. In agent systems, even a small change can trigger significant behavioral changes like a domino effect. This makes writing complex, stateful agent system code exceptionally tricky.

Agents are stateful, and errors can accumulate and amplify. Agents often need to run for extended periods while continuously maintaining and modifying state. This requires our systems to reliably execute code continuously and handle various intermediate errors properly. Without effective fault tolerance mechanisms, small issues can easily escalate into major accidents. More troubling is that once a failure occurs, it is not as simple as restarting the agent from scratch—restarting is time-consuming and disappointing for users.Therefore, we have specifically built a “checkpoint recovery” mechanism to ensure that any errors allow the agent to recover execution from the point of failure. At the same time, we also fully leverage the model’s inherent adaptability: for example, directly informing the agent that “a certain tool has failed” and allowing it to adjust flexibly often yields better results than a rigid restart. Ultimately, we combine Claude’s intelligent adaptability with code determinism guarantees (such as retry mechanisms and periodic checkpoints) to enhance system robustness.

Debugging requires entirely new methods. The decision paths of multi-agent systems are highly dynamic, and the same input often yields different results, making debugging far more challenging than traditional software. For instance, a user might report that “the agent cannot find obvious information,” but upon initial review of the logs, we cannot determine the root cause—was it an erroneous query, a wrong information source, or a failed tool call? To address this,we have launched “full-link production tracking,” which can precisely locate why an agent failed and allow targeted fixes. In addition to conventional observability, we continuously monitor the decision patterns and interaction structures of agents—throughout the process, we ensure user privacy by not recording specific dialogue content. This high-dimensional observation allows us to detect abnormal behaviors, identify root causes, and optimize common failures.

Deployment requires careful coordination. Agent systems are essentially a highly complex network of states, prompts, tools, and execution logic, often running for extended periods. Each time a new version is released, the execution progress of various agents in the system differs. It is not feasible to simply replace everything at once, as this would interrupt ongoing processes. Therefore, we adopt a rainbow deployment strategy, gradually shifting traffic from the old version to the new version, allowing the old and new systems to run in parallel, thus avoiding impacts on running agents.

Synchronization execution creates bottlenecks. Currently, we use a “main agent synchronously waiting for sub-agents to complete before continuing” model, which simplifies coordination but also creates information flow bottlenecks. For example, the main agent cannot guide sub-agents in real-time, and sub-agents cannot collaborate with each other, causing the entire system to slow down due to a single sub-agent blocking progress. If we introduce asynchronous execution, the main and sub-agents can truly operate in parallel and expand in real-time, but this brings new challenges in result coordination, state consistency, and error propagation. As model capabilities improve, the performance gains from more complex asynchronous architectures will become increasingly worthwhile to invest in.

Conclusion

Building AI agents often finds that the last “mile” is the most challenging. The code that seems usable during the development phase requires massive engineering investment to transform into a truly reliable production system. The “composite error” characteristics of agent systems mean that small mistakes in traditional software can lead to global chaos here: one misstep can lead agents down entirely unexpected paths, resulting in unpredictable consequences. Therefore, the gap between prototype and production is far greater than one might imagine.

Despite the challenges, multi-agent systems have demonstrated immense value in open-ended research tasks. Our user feedback indicates that Claude has helped them discover new business opportunities, solve complex medical choices, tackle difficult technical bugs, and even save several days of work in research connections. With rigorous engineering, comprehensive testing, detailed prompt and tool design, robust operational practices, and collaboration among knowledgeable research, product, and engineering teams, multi-agent research systems can be refined to operate reliably at scale. We have already seen that such systems are profoundly changing the way people solve complex problems.

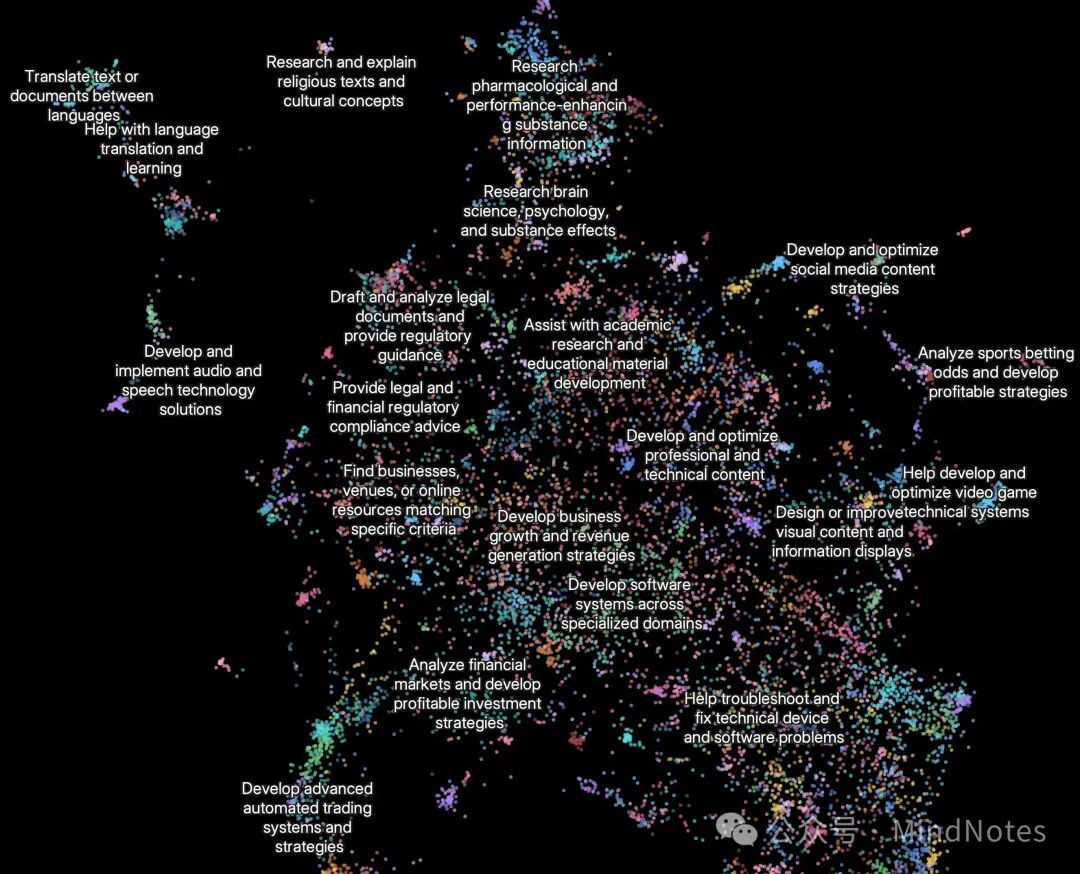

Clio embedded visualization showcases the mainstream scenarios in which people actually use the Research function. The top five applications are: developing software systems across professional fields (10%), optimizing professional/technical content (8%), formulating business growth and revenue strategies (8%), assisting academic research and educational content development (7%), and researching and verifying information about people, places, or organizations (5%).

Acknowledgments

Authors of this article: Jeremy Hadfield, Barry Zhang, Kenneth Lien, Florian Scholz, Jeremy Fox, and Daniel Ford. Thanks to the collective efforts of various teams at Anthropic, especially the application engineering team for their tremendous efforts in driving the launch of the Research function, and also to the early users for their valuable feedback.

Below are some additional tips and practical advice for multi-agent systems.

Final State Evaluation for “Variable State Multi-Turn Agents”

Agents that continuously modify the environment state in multi-turn conversations have special challenges in evaluation. Unlike purely read-only research tasks, every action of such systems can change the environment for subsequent steps, creating strong dependencies, making traditional evaluation methods difficult to cover. Our experience is to focus on “final state evaluation” and not to insist on step-by-step processes. As long as the agent ultimately adjusts the state to the expected outcome, even if the process varies widely, it is acceptable. For extremely complex processes, we can also set “evaluation checkpoints” in stages to determine whether key state changes have occurred, without being overly concerned with the correctness of each intermediate step.

Long Cycle Conversation Management

In production environments, agents often need to handle conversations lasting hundreds of turns, which places high demands on context management. As conversations deepen, traditional context windows quickly become insufficient, so intelligent compression and external memory mechanisms must be relied upon. Our solution is that whenever a task phase ends, the agent automatically summarizes key content into external storage (memory) before entering a new phase. If approaching the context limit, the agent will “hatch” new sub-agents to continue with a fresh context, ensuring task continuity through careful handover mechanisms. If necessary, it can also retrieve research plans and phase content from memory at any time to avoid losing history due to context overflow. This distributed storage strategy ensures that ultra-long conversations remain logically coherent and contextually continuous.

Sub-Agents Directly Output to File Systems to Reduce “Telephone Game” Distortion

For certain results, sub-agents can bypass the main agent and directly output to external file systems, enhancing fidelity and optimizing performance. Not all information needs to be relayed through the main coordinator; instead, sub-agents can save specialized outputs to external systems, only feeding back necessary citation information to the main agent. This approach not only prevents information loss caused by multi-level retelling but also reduces token consumption. Especially for structured output scenarios such as code, reports, and visualizations, sub-agents can generate results using dedicated prompts, yielding far better results than unified coordination summaries.

(End of full text)

Original article link: https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/built-multi-agent-research-system

When 99% of the content devolves into AI-generated noise, only continuous deep reading and independent critical thinking can penetrate the clamor and reveal the truth; those who deeply coexist with AI to solve real problems will ultimately transcend the limitations of the times and refresh the upper limits of life!