Compiled by: Moonlit Lotus

Source: Oncology Information

Currently, JAK inhibitors (JAKi) are the most effective treatment options for myelofibrosis (MF), and research targeting other molecular pathways is actively ongoing. This article briefly introduces the diagnosis and outcomes of MF, focusing on existing treatments and ongoing research. It is evident that there is significant potential for the development of MF treatments, and altering the disease biology may lead to new breakthroughs in MF therapy.

Myelofibrosis (MF)

Myelofibrosis (MF) includes primary myelofibrosis (PMF), polycythemia vera (PPV), and post-essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis [secondary MF (SMF)]. MF is a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) characterized primarily by splenomegaly, systemic symptoms, and blood cell changes, with a tendency towards vascular complications and acute transformation (BP).

The hallmark of MF is the disruption of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, leading to hematopoietic stem cell defects, abnormal proliferation of megakaryocytes, lack of expression of the hematopoietic transcription factor GATA1, abnormal proliferation of granulocytes, and secretion of inflammatory cytokines resulting in increased bone marrow hyperplasia, bone marrow fibrosis (BMF), and extramedullary hematopoiesis. This pathway, along with other pathways associated with MF, can serve as therapeutic targets. Approximately 2/3 of PMF cases carry the JAK2V617F mutation, 1/4 have CALR mutations, and 10% have MPL mutations or are classified as “triple-negative” (TN), with about 80% also carrying other myeloid gene mutations. PPV-MF cases all carry JAK2 mutations, while nearly half of PET-MF cases have JAK2V617F, 30% have CALR, and about 5-10% have MPL mutations or are TN.

Current treatments for MF include anemia management, hydroxyurea, JAK inhibitors (JAKi) such as ruxolitinib (RUX), fedratinib (FEDR), pacritinib (PAC), momelotinib (MMB), allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT), and clinical trials. This article reviews the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of PMF and PPV/PET-MF.

Diagnostic Criteria

According to the latest fifth edition classification released by the ICC and WHO, MF remains a classic BCR:ABL1-negative MPN, with mutations in the JAK2, CALR, and MPL genes being driving events. More than half of MF cases also have mutations in TET2, ASXL1, and DNMT3A, while mutations in splicing regulators, chromatin structure, epigenetic functions, and cell signaling genes are less common.

The diagnostic criteria for PMF and PPV/PET-MF emphasized by the ICC highlight the abnormal morphology of megakaryocytes, the typical age-related MF pattern, and the role of BMF. The clustering of megakaryocytes does not exclude essential thrombocythemia (ET), and the assessment of classic driver mutations must also consider non-classic JAK2/MPL mutations (VAF should be >1%), with low JAK2-VAF cases needing to check for coexisting classic CALR/MPL mutations.

In summary, the BM morphological assessment of MF remains primarily subjective and qualitative. Recent methods such as deep learning can capture the morphological features of MF in BM smears.

Results

The median overall survival (OS) for pre-PMF, overt PMF, and SMF is 14 years, 6-7 years, and 9 years, respectively. The main sources of mortality risk stem from disease-driven myeloid malignancies, high infection rates, and cardiovascular-related deaths. In recent decades, the survival of MF patients has improved due to early diagnosis, a better understanding of the pathogenesis, standardized SCT candidate criteria, widespread use of JAKi, and improved supportive care.

1. Survival Prediction

The IPSS model was initiated in 2009, and the model used for PMF in the 2022.3 NCCN guidelines is MIPSS-70 or MIPSS-70+ version. If molecular results are unavailable, DIPSS+ is used; if karyotype results are unavailable, DIPSS is used, and MYSEC-PM is used for SMF. These models reflect the evolving understanding of MF.

DIPSS is easily accessible and simple to apply, while other assessments require relevant technology and 2-4 weeks of testing time. DIPSS/DIPSS+/MYSEC-PM models are used for patients of all ages, while MIPSS-70 is used for SCT decision-making in patients <70 years old. In all models, parameters such as age, degree of anemia or leukocytosis, blood blast cells, and systemic symptoms are crucial. DIPSS+ adds indicators for thrombocytopenia and RBC transfusion, while MIPSS70/version introduces BMF grading. Cytogenetic testing in PMF is not common, with normal and adverse karyotypes being 60-70% and 11-22%, respectively. DIPSS+, GIPSS, and MIPSS-70+/version include karyotype. High-risk genes associated with PMF outcomes (HMR, ASXL1, SRSF2, EZH2, IDH1, IDH2), U2AF1Q157 mutations, and CALR or CALR1 type/1-like deletions have been incorporated into MIPSS-70/version. In the original cohort, 80% of individuals had no CALR1 type mutations, 31-41% carried HMR mutations, and 8-9% had ≥2 HMR mutations.

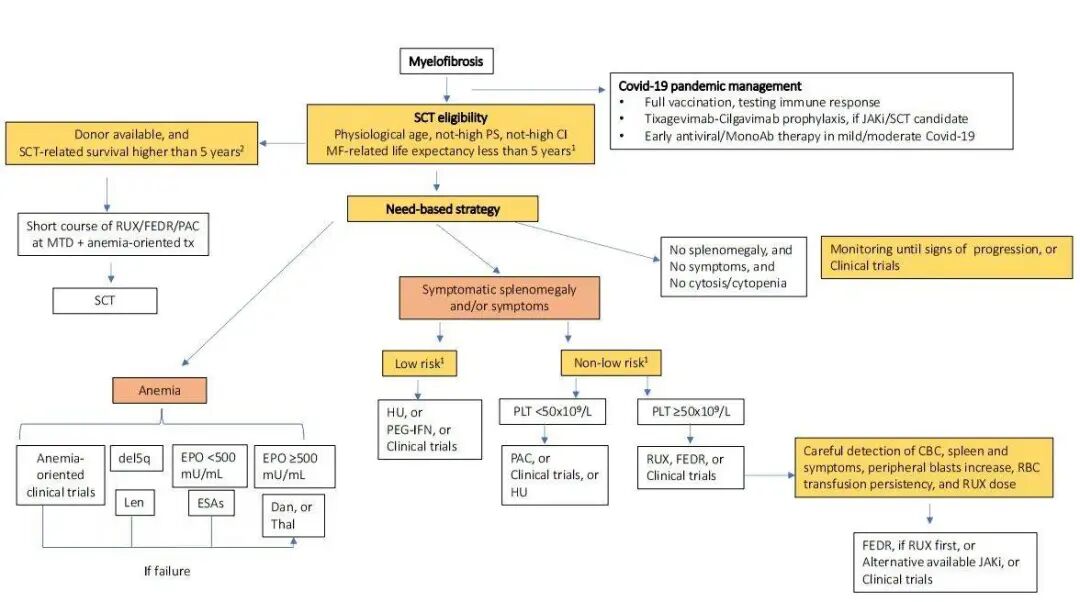

Patient stratification is related to treatment decisions (Figure 1), especially when selecting SCT patients. We believe that multiple PMF models should be evaluated simultaneously and documented, for which we have developed a dedicated PMF web calculator (https://pmfscorescalculator.com). In daily practice, survival predictions across different models should remain consistent for decision-making (especially for SCT), but inconsistencies can be challenging. For example, a 52-year-old patient with JAK2 mutation PMF has a DIPSS risk of intermediate-1 with a median OS of 14 years; BMF grade 2, normal karyotype, and ASXL1 mutation give a MIPSS-70 risk of intermediate with a median OS of 6-7 years; MIPSS-70+V2 gives a high-risk classification with a median OS of 4 years. In this case, monthly follow-ups should be conducted to find a donor, and SCT should be considered upon signs of clinical progression.

Figure 1: MF Diagnosis and Treatment Process

In addition to models, other factors are also related to survival: morphologically determined BM or blood blast cells; blood CD34+ cells and flow cytometry-determined neutrophil side scatter reduction, which need to be analyzed in conjunction with conventional PMF risk factors; mutations in TP53, CBL, or N/KRAS; PMF bone marrow depletion phenotype; poor performance status; quality of life scores; and comorbidities.

2. Myeloid Evolution and Cardiovascular Event Prediction

10-15% of MF evolves into myeloid BP, after which the survival period is very short. Both DIPSS and MIPSS-70/70+ models can be used to predict PMF BP, with other factors associated with poorer survival without BP including transfusion-dependent anemia, elevated blood interleukin-8 and CRP, single chromosome karyotype, TN, RAS/MAPK pathway gene alterations, RUNX1, CEBPA, and SH2B3 mutations.

Information on cardiovascular events in MF is limited, but their incidence is not negligible: PMF has an incidence of 1.6-2.3% per year, and SMF has 1.5%. Age >60, JAK2, and IPSS scores are predictors of cardiovascular events in PMF, and reducing blood cell therapy has a preventive effect on cardiovascular events in SMF. Antiplatelet therapy for MF needs to be evaluated, balancing the risk of bleeding (estimated at 1.5% per year), with higher IPSS classifications and anticoagulants increasing the risk of bleeding. Pulmonary hypertension in MPNs is not uncommon and requires careful monitoring of symptoms through transthoracic echocardiography.

Treatment

The MF treatment strategy proposed in this review does not differentiate between PMF and SMF (Figure 1). First, it determines whether SCT is indicated, and then treatment is tailored to control anemia and improve splenomegaly/symptoms based on risk stratification. Bone marrow hyperplasia, i.e., leukocytosis and/or thrombocytosis, is usually associated with symptoms or splenomegaly and should be addressed. Hydroxyurea (HU) can control blood cell proliferation; in the MOST study, 46% of patients receiving HU treatment were low-risk. In a study of HU treatment for MF, 40% of patients showed clinical improvement, with a duration of response (DOR) of 13 months.

Considerations During Covid-19

For MF patients, inappropriate discontinuation of RUX after exposure to SARS-CoV-2 may lead to adverse outcomes. Patients on RUX treatment have impaired immune responses to Covid-19 vaccines. After SARS-CoV-2 infection, MF patients on RUX treatment or undergoing SCT are candidates for antiviral therapy (it is recommended to reduce RUX dosage when using nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) and to use tixagevimab/cilgavimab for the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Treatment of Anemia

Treatment of anemia is challenging, as anemia can be a primary clinical manifestation or a symptom accompanying splenomegaly, occurring during disease progression or as a result of JAKi treatment. Improving anemia can enhance quality of life, control transfusions, and reduce iron load and related consequences such as infections, endocrine, liver, and cardiac complications. The safety and efficacy of iron chelation therapy in MF have not been widely evaluated. Retrospective studies indicate that RUX and luspatercept treatment for MF show that 48% of patients have a sustained response to iron chelation therapy for 3 months.

The response to anemia treatment is defined according to IWGMRT standards: transfusion-dependent (TD) patients do not require transfusions; transfusion-independent (TI) patients have an Hb increase >2g/dL. Among 163 patients treated with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, 53% (29% TD, 57% TI) had a treatment response, with a median DOR of 19 months, regardless of JAKi use. In 50 patients treated with danazol for anemia, 30% had a treatment response (18% TD, 43% TI). The treatment effects of thalidomide or lenalidomide are limited, with the latter being effective for del(5q). In the RESUME study, pomalidomide failed to meet the study endpoint of RBC-TI superiority over placebo. In a phase II study, among 91 anemic patients treated with pomalidomide combined with RUX, the IWGMRT response rate at 1 year was 10-21%.

Currently, there is exploration of targeting TGFβ superfamily alterations in the BM microenvironment cytokines to improve anemia. The phase III INDEPENDENCE study aims to compare the efficacy of the Smad2/3 pathway ligand trap luspatercept with placebo. In the phase II study of luspatercept, either alone or in combination with RUX, among 34 TI patients, 10% and 21% had treatment responses, while among 43 TD patients, 10% and 32% had treatment responses, with durations of 49 and 42 weeks, respectively. In these cohorts, 38% and 46% of patients had a reduction in RBC transfusion burden of ≥50%. Soatercept is also a TGFβ superfamily signaling inhibitor, and among 56 patients treated alone or in combination with RUX, 30% and 32% had treatment responses.

KER050, a modified ActRIIA ligand trap, is being studied for its effects on erythroid progenitors. The ALK-2 small molecule inhibitor INCB000928 works by reducing hepcidin expression, while another method to reduce hepcidin expression is through the use of humanized anti-hemojuvelin monoclonal antibody DISC-0974. In the MOMENTUM study, patients with symptomatic anemia were treated with MMB or danazol, with a TI rate of 31%. The SYMPLIFY study confirmed this effect, showing that MMB can inhibit JAK1/2 and ACVR1, the latter interfering with excessive hepcidin production related to inflammation.

Results of JAKi Treatment in Treatment-Naive Patients

JAKi have entered clinical use, with RUX and FEDR approved by the FDA and EMA, and PAC approved by the FDA. Phase III studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of JAKi primarily included intermediate-2/high-risk patients, with primary endpoints being a ≥35% reduction in spleen volume (SVR35) and a ≥50% reduction in total symptom score (TSS50) at 24 weeks. Except for the SYMPLIFY-1 study comparing RUX with MMB, no other studies directly compared JAKi. Meta-analyses indicate that the efficacy of MMB and FEDR is comparable to RUX.

Overall, among treatment-naive patients achieving SVR35 and TSS50, RUX achieved 42% and 46%, FEDR achieved 47% and 40%, PAC achieved 19% (intermediate-1, 56%), and MMB achieved 27% and 28% (intermediate-1, 22%), while jakatinib achieved 31-54% and 57-70% (intermediate-1, 33%).

1. Impact of JAKi on Survival

It should be noted that survival is not the primary endpoint of existing studies. The COMFORT-I/II studies of RUX showed a 30% reduction in mortality for intermediate-2/high-risk patients; the JAKARTA study showed superior PFS for FEDR; the SYMPLIFY-1 study showed a 6-year survival rate of 56% for MMB, with TI results associated with improved 3-year survival; the MOMENTUM study showed a trend towards improved 24-week survival for MMB compared to danazol; and survival was similar for patients with very low platelet counts treated with PAC and BAT.

2. Treatment of Splenomegaly in Thrombocytopenic Patients

Currently, there is no specific treatment to improve platelet counts, with some patients responding to danazol (23%) and pomalidomide (22%). The Syk inhibitor fostamatinib is being evaluated for its potential to increase platelet counts. All JAKi are applicable for patients with platelet counts of 50-100×109/L, with the following results for achieving SVR35: 17% of 66 patients treated with RUX (intermediate-1, 22%), 42% of 12 patients treated with FEDR in the JAKARTA sub-analysis, 17% of 72 patients treated with PAC in the PERSIST-1 sub-analysis, and 22% of patients treated with MMB in the MOMENTUM sub-analysis (platelets <150×109/L). Patients with platelet counts <50×109/L have a higher risk of bleeding and should not use standard doses of RUX or FEDR, especially PAC. The PACIFICA study aims to compare PAC with BAT in this scenario. In the PAC203 study, 24 patients treated with PAC achieved 17% SVR35, with 33% experiencing grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia, rarely leading to dose reduction or discontinuation (approximately 4% each).

3. Management of Splenomegaly in Anemic Patients

All anemia treatment drugs can be combined with RUX to balance JAKi-related anemia with efficacy, and preventing TD is a real challenge in practice. In the REALISE study (intermediate-1, 17%), RUX treatment for anemic patients started at 10mg BID and was gradually increased, with 56% of patients achieving ≥50% reduction in spleen length.

New Combination Treatments for Treatment-Naive Patients with JAKi

As the efficacy of JAKi monotherapy is limited, combining RUX with non-JAK targeted inhibitors for treatment-naive patients has become a direction for development. Although most studies have used SVR35 as the primary endpoint, it has been found that adjustments in MF biology can yield survival benefits or at least achieve sustained stable clinical responses. Phase III studies MANIFEST-2, TRANSFORM-1, and LIMBER-313 are comparing small molecules pelabresib, navitoclax, and parsaclisib combined with RUX against RUX monotherapy, with 24-week SVR35 as the primary endpoint.

In the MANIFEST study, the oral BET inhibitor pelabresib combined with RUX showed that among 84 patients (HMR, 55%; intermediate-1, 24%), 68% achieved SVR35, with 86% maintaining the response, and 56% improved Hb and achieved TSS50, with grade 3-4 anemia and thrombocytopenia occurring in 34% and 12%, respectively. In addition to affecting several pro-inflammatory cytokines, this combination therapy can induce early morphological changes in BM, such as ≥1 grade improvement in BMF, reduced megakaryocytes, increased megakaryocyte spacing, and increased erythroid cells, all of which are associated with SVR. In the REFINE study, the oral BCL-XL/BCL-2 inhibitor navitoclax combined with RUX showed that among 32 patients (intermediate-1, 31%), 63% achieved SVR35, with a 1-year response rate of 93%, 41% achieving TSS50, and 40% of anemic patients responding, with grade 3-4 anemia and thrombocytopenia occurring in 34% and 47%, respectively, and 27% showing ≥1 grade improvement in BMF. Among 10 treatment-naive patients with JAKi (intermediate-1, 40%) treated with the nuclear export protein inhibitor selinexor, preliminary data showed that 4/5 patients achieved SVR35 at 12 weeks.

Transitioning from RUX to Second-Line Treatment

The optimal timing for transitioning treatment has not been determined, as RUX responses are inconsistent; some patients may show signs of progression but still benefit overall. In practice, we transition treatment before the complete loss of RUX activity, i.e., when dose adjustments, blood counts, and blast cells, spleen size, and symptoms continue to worsen, or when spleen length is reduced by >50% but remains splenomegaly. About half of patients discontinue RUX after 3 years, primarily due to disease progression or side effects, with a survival of 13 months after discontinuation. Progression or poor response definitions include IWGMRT standards (progressive splenomegaly, BP) and/or continuously worsening anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, and the presence of certain mutations. To identify predictive factors for poor survival after 6 months of RUX treatment, we developed the RR6 model, which calculates the touchable spleen length, RBC transfusion needs, baseline RUX dosage, and treatment duration of 3 or 6 months to stratify patients early.

Results of JAKi Treatment in JAKi-Experienced Patients

In the JAKARTA-2 study, FEDR was used for patients who failed RUX. The RUX failure criteria showed that 30% of patients achieving SVR35 had a DOR that did not reach the median, with TSS50 at 27% and a 1-year survival rate of 84%. These results serve as a reference standard for second-line treatment. Additionally, there was no significant difference in SVR35 between patients with platelet counts < or >100. In cases of gastrointestinal toxicity, thiamine testing and dose reduction are recommended to ensure safety. The FREEDOM2 study is currently comparing FEDR with BAT.

The SIMPLIFY-2 study found that the SVR35 of MMB was not superior to BAT, but TSS50 was better, with secondary endpoints showing improvements in transfusion needs. The MOMENTUM study further showed that 23% of patients achieved SVR35, with 61% and 28% experiencing grade 3-4 anemia and thrombocytopenia, and 4% experiencing peripheral neuropathy (PN, excluding ≥2 grade PN).

Results of Non-JAK Targeted Inhibitors as Monotherapy or Combined with RUX in JAKi-Experienced Patients

Phase III studies TRANSFORM-2, LIMBER-304, IMpactMF/MYF3001, and BOREAS are ongoing, evaluating RUX combined with navitoclax or parsaclisib, as well as monotherapy with metelstat and navtemadlin.

In the REFINE study, RUX combined with navitoclax showed that among 34 patients (58% HMR, 44% intermediate-1), 24 weeks saw 26% of patients achieving SVR35, with a median DOR of 14 months, 30% achieving TSS50, an anemia response rate of 64%, 33% showing ≥1 grade improvement in BMF, and 28% of HMR and 17% of non-HMR patients showing a VAF reduction of ≥20%. Patients with improvements in BMF and VAF had longer survival (median OS not reached and 28 months), supporting the combination treatment of disease biology adjustments. Thrombocytopenia is common, reversible, and not associated with bleeding. Monotherapy with navitoclax showed inferior results compared to combination therapy. Other anti-apoptotic drugs, such as IAP antagonists and SMAC mimetics like LCL-161, are also being evaluated for MF treatment, with an ORR of 30% among 50 patients with reduced IAPs.

Selinexor treatment in 12 patients (67% HMR) showed that 22% achieved SVR35. In patients with poor RUX responses, the next-generation PI3Kδ inhibitor parsaclisib was added, with half of the patients achieving SVR10, 9% achieving SVR35, and 28% experiencing new grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia, with 12% of patients with platelet counts of 50-100×109/L achieving SVR35. The telomerase inhibitor metelstat showed low SVR35 (10%) and TSS50 (32%), but the IMbark study found its biological effects promising, with higher doses of metelstat promoting ≥1 grade improvement in BMF, driving mutation VAF reductions of ≥25%, and cytogenetic responses, with biological improvers tending to have longer survival. 49%, 44%, and 36% of patients experienced grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia, with 37% and 21% experiencing infections and bleeding.

In the KRT-232-101 study, 25 patients were treated with the MDM2 inhibitor navtemadlin, achieving SVR35 and TSS50 of 16% and 30%, respectively. The most common treatment-related adverse events were diarrhea, nausea, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. Biological effects were observed as reductions in blood CD34+ cells, driving gene VAF reductions of ≥20%, and undetectable driving/HMR gene VAF, with ≥1 grade improvement in BMF, all of which were associated with SVR, but no reports of survival correlation.

In the phase II MANIFEST study, pelabresib alone or in combination with RUX showed that among 86 patients (8% intermediate-1), 20% and 37% achieved SVR35 and TSS50, respectively, with 34% transitioning from TD to TI, and 26% showing ≥1 grade improvement in BMF. In the 24-week monotherapy group (86 patients, 8% intermediate-1), 11% and 28% achieved SVR35 and TSS50, respectively, with 16% transitioning from TD to TI. Among 7 patients with BMF improvement, 71% had a response in Hb. BET inhibition is a promising target, and other drugs are under investigation: ABBV-744, BMS-986158, and mivebresib.

Epigenetic modifiers such as LSD1 can be treated with bomedemstat (IMG-7289-CTP-102 study). Among 89 patients (42% HMR), 28% achieved SVR20, and 24% achieved TSS50, with nearly 90% maintaining stable Hb. 31% and 48% showed ≥1 grade improvement in BMF and a 39% overall reduction in VAF, primarily affecting JAK2 and ASXL1. Targeting epigenetic modifiers with panobinostat combined with RUX treatment showed that 61% of patients had a spleen length reduction of ≥50%, with no biological effects observed.

1. Targeting the Microenvironment

The BM microenvironment can be targeted with PRM-151 (recombinant human pentraxin-2), with 1/4 of patients showing reduced BMF and slight effects on splenomegaly; the AURKA inhibitor alisertib showed no clinical effects but restored normal morphology of megakaryocytes and GATA1 expression; studies targeting connective tissue with LOXL2 inhibitors are ongoing, utilizing their selective GSK-3β inhibitory properties to reverse pathological fibrosis; anti-IL-1β monoclonal antibody canakinumab primarily neutralizes interleukin-1β signaling; the β-3 adrenergic agonist mirabegron, while not reducing JAK2-VAF, has a microenvironment-modulating effect. Targeting BMF has a greater effect in early MF than in late stages.

2. Targeting Signaling Pathways

Glasdegib or vismodegib targeting the Hedgehog signaling pathway shows moderate activity against MF. TL-185, which affects BTK signaling, combined with navtemadlin, exerts a synergistic effect as a cytoskeletal modulator and cell death agent.

3. Immunotherapy

Numerous studies have investigated IFN treatment for MPNs. Among 30 low-risk MF patients treated with IFN-α, 15 showed some degree of response, and among 12 patients with splenomegaly exceeding 4cm beyond the left costal margin, 4 had a spleen reduction of >50%. Among 62 patients (53% DIPSS low-risk) treated with pegylated IFN-α2a for 3.2 years, the median OS was 7.2 years, with 73% discontinuing treatment, half due to resistance and half due to intolerance. In the COMBI study, 18 MF patients treated with pegylated IFN-α2a combined with RUX showed a 2-year dropout rate of 32%, with no significant clinical efficacy, but a reduction in JAK2-VAF was observed. IFN treatment appears more reasonable in early MF.

Theoretically, targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis could release suppressed immune responses, but nivolumab was ineffective, and studies on durvalumab and sabatolimab (TIM-3 inhibitor) have been paused. The CALR mutation-derived tumor-specific antigens have high immunogenicity, leading to the development of CALR mutation-derived peptide vaccines, which have undergone phase I clinical trials with significant T-cell responses but clinical ineffectiveness. Another CALR mutation-derived peptide vaccine study showed efficacy. A viral vector tumor vaccine VAC85135 combined with ipilimumab for MF is currently recruiting.

4. Stem Cell Transplantation

SCT is the only curative method for MF: 1/2 of patients remain cured at 5 years. The CIBMTR retrospective study compared SCT with non-SCT cohorts, finding that SCT provided a survival advantage of over 1 year for patients with ≥intermediate-1 risk, at the cost of early non-relapse mortality.

EBMT and ELN are revising SCT treatment guidelines for MF, addressing core issues in daily practice: (1) Patient selection. Age alone is no longer a limitation; assessments of MF-related and post-SCT outcomes must be conducted, and transplant candidates must be informed that patients with expected survival <5 years can be accepted (intermediate-2 and high-risk DIPSS or MYSECPM/high-risk MIPSS-70; Figure 1). Selecting SCT for patients with expected survival <5 years is controversial (extremely high-risk MTSS); (2) Pre-SCT splenectomy. EBMT-related documents will be published soon; (3) SCT bridging therapy. Patients with clinical improvement on RUX treatment have a lower risk of relapse, with higher 2-year EFS rates, thus we believe that using new combination therapies before SCT to improve clinical outcomes is meaningful; (4) Donor selection. Among 233 MF patients, the 5-year survival rate after SCT was 56% for matched sibling donors, 48% for well-matched donors, and 34% for partially matched/unmatched donors. Preliminary data on haploidentical transplantation demonstrate its feasibility in patients without suitable HLA donors.

References

Passamonti F, Mora B. Myelofibrosis. Blood. 2022; blood.2022017423. doi:10.1182/blood.2022017423

Editor: Luna

Layout Editor: Luna

Copyright Notice: This article is intended for medical professionals only. Unauthorized publication or distribution is prohibited. Personal sharing is welcome, but any media or website wishing to reproduce or cite content owned by this site must obtain authorization and prominently indicate “Reprinted from: Liangyi Hui – Oncology Doctor APP”.