/Reading China: Enjoying Good Reading Time/

“Montesquieu on China”

By Montesquieu

Translated by Xu Minglong

Published by Commercial Press, December 2016

Since the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China, a wave of Western learning has gradually flowed into China, with “The Spirit of the Laws” being one of the representative Western classics. Over the past century, Chinese scholars and even ordinary people have become quite familiar with the great Enlightenment thinker Montesquieu. However, many are unaware that this great Enlightenment thinker of the 18th century was also deeply interested in China, and his works contain numerous discussions about the country.

How did Montesquieu obtain information about China, a distant civilization across the ocean in the 18th century when transportation was inconvenient? Later research indicates that Montesquieu gained a wealth of information about China through interactions with several missionaries who had lived there, which shaped his impressions of ancient China.

The collection published this time, “Montesquieu on China,” includes discussions about China scattered throughout his works such as “The Spirit of the Laws,” “The Persian Letters,” “Reflections on the Causes of the Grandeur and Decadence of the Romans,” “Geography,” and “Essays.” Through these discussions, readers may gain a different perspective on studying Montesquieu and his thoughts.

Chinese legislators regard peace as the primary goal of governance. In their view, obedience is an effective means to maintain peace. Based on this idea, they believe that people should be encouraged to respect their fathers, and they spare no effort in this regard. Respect for fathers inevitably extends to respect for all figures who can be seen as fathers, such as elders, teachers, officials, and the emperor.

Respect for fathers means that fathers reciprocate their children’s love. Similarly, elders reciprocate their care for the young, officials for their subordinates, and emperors for their subjects. All of this constitutes etiquette, and etiquette forms the universal spirit of the nation.

The Chinese Empire is built on the concept of family governance. Whether a daughter-in-law serves her mother-in-law every morning is not of great importance. However, if we consider that these daily details continuously evoke a feeling that must be engraved in the heart, and that this feeling in everyone’s heart constitutes the spirit of governance in the Chinese Empire, we will understand that none of these specific actions is dispensable.

——Excerpt from “Montesquieu on China”

▲

Montesquieu’s Perspective on China

Xu Minglong

Since the mid-17th century, a wave of interest in understanding and studying China gradually formed in Europe. In 1685, due to the personal involvement of Louis XIV, France sent five Jesuit missionaries to China; in 1698, the first French merchant ship, the “Amphitrite,” made its maiden voyage to China. Subsequently, the number of French missionaries and merchants coming to China increased, and information about China flowed continuously to France, placing France in a leading position in the “China craze” in Europe.

It is no exaggeration to say that the well-known French literati of that time were all concerned with or studying China, especially those great figures later known as Enlightenment thinkers. Many of them used China as a model in their struggles against feudalism and in their efforts to establish an ideal bourgeois kingdom; they passionately praised China’s political system, philosophical ideas, and ethical concepts. Among this chorus of praise for China, we can see famous Enlightenment scholars such as Voltaire, Quesnay, Holbach, Diderot, and Rousseau.

Montesquieu, who lived slightly earlier than these Enlightenment thinkers, is remembered as one of the pioneers of Enlightenment thought in France. Throughout his life, he also showed great enthusiasm for understanding and studying China, leaving behind a wealth of records and comments about the country. However, unlike Voltaire and Quesnay, he never wrote a monograph or a paper that focused solely on discussing China. His discussions about China are scattered throughout his various works.

▲ “The Spirit of the Laws”

According to my statistics, Montesquieu discussed China in the following works: “The Persian Letters,” “The Spirit of the Laws,” “Thoughts,” “Essays,” “Geography,” and “On General Despotism.” In these works, China occupies an important position. For example, “The Spirit of the Laws” has thirty-one chapters, with as many as twenty-one chapters and fifty-three sections mentioning China. Moreover, Montesquieu’s unpublished work “Geography” is a notebook for collecting materials for writing, most of which consists of excerpts and reflections from books he read about China, making it a “China anthology.”

Although Montesquieu discussed China hundreds of times in his works, he was not a member of the chorus praising China. On the contrary, he held a fundamentally negative attitude towards China and criticized its political system, which led to dissatisfaction from Voltaire and Quesnay, who frequently rebutted him. Scholars have traditionally focused on the studies of Voltaire and others who held a praising attitude towards China, which is certainly necessary. However, Montesquieu, as an important Enlightenment thinker who devoted considerable energy to understanding and studying China, has unique insights on the country, and thus should not be neglected. This article attempts to raise this issue for discussion among experts and knowledgeable individuals.

01

Despite the vast distance between China and France, and the inconvenient transportation at that time, Montesquieu, eager to understand China, never visited this ancient and distant country. His understanding of China primarily came from reading and indirect contact.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, most French people learned about China through the translations and writings of missionaries who came to China. Montesquieu was no exception. According to his own records and other materials, he read at least the following books about China:

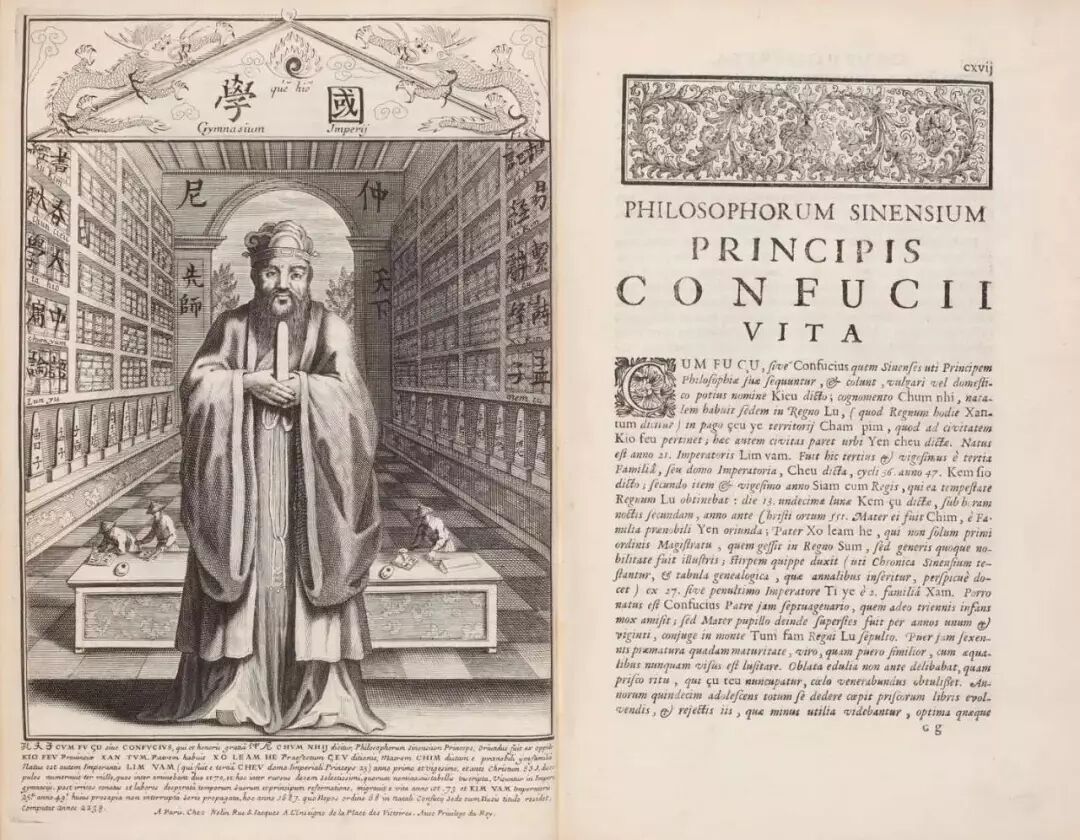

Ph. Couplet (known as Bai Yingli), “Confucius, Sinarum Philosophus” (1687); “Chronological Table of China” (1683);

“Letters Edifying and Curious” (1703-1774);

Du Halde, “Description of the Empire of China” (1735);

C. Visdelou (known as Liu Ying), “General History of the Tartars”;

G. Dampier, “New Voyages Around the World” (1711);

“The Current Situation of Taiwan”;

E. Isbrand, “Voyage from Moscow to China”;

L. Lange, “Voyage of the North” (1711);

G. Anson, “A Voyage Round the World” (1740-1744, 1749);

Renaudot, “Ancient Relations of the Indies and China” (1718);

La Croix, “History of the Great Genghis Khan”;

A. Kircher, “Illustrated China” (1670).

The aforementioned works about China can be roughly divided into two categories. One category comes from Christian missionaries who came to China. These missionaries stayed in China for a long time, had the opportunity to interact with people from various social strata, and some even had access to high-ranking officials and the emperor due to their positions in the court, so their observations and understanding of China were relatively in-depth.

Generally speaking, they had more praise than criticism for China. Their works, represented by “Letters Edifying and Curious” and “Description of the Empire of China,” were read by Montesquieu around 1734. He read “Description of the Empire of China” between 1735 and 1738.

The other category consists of travelogues by diplomats and merchants. These individuals stayed in China for a short time, and their visits were limited to Beijing or coastal ports. Due to language barriers and other reasons, their direct contact with Chinese people was minimal, leading to a superficial understanding of China. Therefore, their travelogues often skimmed the surface, relied on hearsay, and were not very reliable, sometimes even containing malicious slanders. Montesquieu had a strong interest in various travelogues, and naturally, he loved to read those about China.

▲ “Confucius, Sinarum Philosophus”

Existing materials indicate that as early as 1713, Montesquieu began reading books about China. That year, he read Bai Yingli’s “Confucius, Sinarum Philosophus,” “Chronological Table of China,” and Kircher’s “Illustrated China.” “Confucius, Sinarum Philosophus” includes excerpts from “The Great Learning,” “The Doctrine of the Mean,” and “The Analects,” as well as an introduction to Confucius’s biography and commentary on his thoughts and teachings. “Chronological Table of China” briefly summarizes Chinese history from 2952 BC to 1683 AD. “Illustrated China” discusses China’s religion, natural conditions, and customs, with rich illustrations, widely circulated, and is considered an authoritative work on early China in Europe. Bai Yingli’s two books were written in difficult Latin, and Montesquieu not only read them carefully but also translated some chapters into French and wrote thousands of words of notes expressing his views.

Another way Montesquieu learned about China was through interactions with Chinese individuals and French people who had been to or were familiar with China.

Through his teacher Pierre-Nicolas Desmolets at the Collège de Juilly, he met sinologist Fourmont and orientalist Fréret. Fourmont had profound research in sinology and participated in compiling Chinese grammar and dictionaries. He maintained long-term correspondence with French missionaries in China and had considerable knowledge about the country. Although there are no written records of Montesquieu’s friendship with Fourmont, one incident gives us reason to believe that their relationship was quite close.

In 1731, the French missionary Prémare (known as Ma Ruose) sent a French translation of “The Orphan of Zhao” back to France through a friend, giving it to his friend Fourmont. This translation was included in Du Halde’s “Description of the Empire of China,” first published in 1735, while the standalone version was not published until 1755. However, Montesquieu had already recorded his thoughts on reading “The Orphan of Zhao” in his “Essays” in 1733. This means he had read the manuscript before the translation was published, and the only two people who could have provided the manuscript were Du Halde and Fourmont. Existing materials indicate that Montesquieu had no correspondence with Du Halde, so it is likely that Fourmont provided the manuscript, indicating their relationship was indeed significant.

▲ Madame Geoffrin’s salon reading Voltaire’s “The Orphan of China,” with Montesquieu, Rousseau, and others depicted in the image

Fréret was a well-known scholar at the time, with considerable research on China and knowledge of Chinese. He had planned to travel to China in 1715 but was unable to do so for various reasons. He maintained close contact with many people familiar with China and had a good relationship with Montesquieu. Although we do not know how much information and materials Montesquieu received from him about China, one thing is certain: their shared interest in China was one of the foundations of their friendship, and discussing issues related to China was an important aspect of their interactions.

Through Fréret or Desmolets, Montesquieu met a Chinese individual named Huang (Houang-Ji, also written as Ouange Gé, later confirmed as Huang Jialue) who lived in Paris in 1713. He was from Xinghua, Fujian, converted to Christianity in 1679, and took the Christian name Arcadio upon baptism. In 1703, he accompanied the French missionary Artus de Lionne (known as Lang Hongren) to France and worked at the Royal Library.

He had previously collaborated with Fréret and Fourmont to compile books on the Chinese language and also worked as a translator. After Montesquieu met Huang, they had extensive conversations covering various topics such as Chinese philosophy, religion, punishment, etiquette, language, the imperial examination system, politics, and history; during the conversation, Huang even sang a Chinese folk song for Montesquieu.

Montesquieu placed great importance on this conversation, and three notes recounting it have been found among his existing manuscripts, the longest of which spans over twenty pages. One note appears in “Essays,” consisting of only a few lines, describing Huang’s feelings when he first arrived in Paris. The second note, which has not been included in any existing versions of Montesquieu’s complete works, was discovered in the Bordeaux Municipal Library in the late 1950s. This note was found in the same volume as Montesquieu’s notes on reading “Confucius, Sinarum Philosophus” and is presumed to have been written shortly after his conversation with Huang in 1713. At this time, Montesquieu was beginning to conceive “The Persian Letters.” Later, “The Persian Letters” utilized Huang’s character and the content of their conversation.

▲ “The Persian Letters”

The second note appears in the second volume of “Geography,” with similar content but slight differences in wording. According to research, this note was written between 1734 and 1738, suggesting that this was a revised copy of the second note. At this time, Montesquieu was preparing to write “The Spirit of the Laws.” If it is not a coincidence, then more than twenty years later, Montesquieu’s reorganization of this note was likely for the purpose of writing “The Spirit of the Laws.”

Huang was Montesquieu’s first direct contact with a Chinese person and the only one in his lifetime. On November 15, 1713, Montesquieu’s father passed away, and he returned to Bordeaux for the funeral, leaving for eight years, not returning to Paris until he finished writing “The Persian Letters.” Huang had already passed away in 1716 due to tuberculosis.

During his travels in Italy, Montesquieu met the missionary Fouquet (known as Fu Shengze). Fouquet was a Frenchman who arrived in China in 1699 and stayed for twenty years in Jiangxi and Fujian. In 1720, he returned to Europe on a church mission and met Montesquieu in Rome in 1729. During Montesquieu’s stay in Rome, he met Fouquet several times, and he mentioned in “Italian Travels” that Fouquet was one of the people he conversed with the most during his time in Rome. “Essays” records a conversation they had on February 1, 1729, covering topics such as Chinese history and ethical concepts.

On June 2, 1737, Montesquieu met the missionary Assémani in Paris. He was a Jesuit sent by France to Syria and had been to China. During this conversation, he introduced Montesquieu to some situations regarding the disputes over Chinese etiquette among missionaries.

▲ De Mairan

De Mairan, the secretary of the French Academy of Sciences, was an old friend of Montesquieu. As early as 1721, they had correspondence and exchanges. Like many scholars in France at the time, De Mairan was very concerned about China. He frequently corresponded with missionaries who had been to China. “Letters Edifying and Curious” includes letters from the missionary Parennin (known as Baduoming) written to him between 1730 and 1740, introducing China’s science and technology, history, and current situation, as well as discussing some of China’s problems. Montesquieu and De Mairan often discussed China, and even in 1755, the year of Montesquieu’s death, they had a heated debate over their differing opinions on China. Afterward, Montesquieu felt it was inappropriate and wrote to his other close friend Guasco, asking him to convey his apologies to De Mairan, so that this debate would not affect their friendship.

From the conversation with Huang in 1713 to the debate with De Mairan in 1755, Montesquieu’s interest in China remained strong for over forty years. During this period, the disputes over Chinese etiquette among European missionaries in China reached a climax, and a large number of works about China were published. Scholars such as Malebranche, De Surgy, and Poivre also published works about China during this period, not to mention the works of Sir William Temple that were published in 1729. Montesquieu had the opportunity to discuss these books about China, but we currently lack materials to confirm this.

Although Montesquieu never had the chance to see China with his own eyes, the materials he accessed about China at that time were relatively rich. This provided him with very favorable conditions for studying and discussing China, and for using his research and understanding of China as one of the materials and foundations for establishing his own theories, making him, like Voltaire and Quesnay, recognized as one of the Frenchmen who understood China the most in the 18th century.

02

As early as 1713, when Montesquieu began to access materials about China, his doubts and denials about the country began to surface. When reading “Confucius, Sinarum Philosophus,” he often disagreed with Bai Yingli’s analysis of Confucius’s thoughts. He said, “He (Bai Yingli) interprets Chinese terms with bias to support his argument; I have found many errors.”

In the records of his conversation with Huang, this attitude is even more evident. He said, “Let us rid ourselves of prejudices; we have spoken too well of them (the Chinese) and may have overstated.” “If the Chinese government is truly so admirable, how could the Tartars have suddenly become the masters of this country?”

Later, when he read the works of missionaries, he often expressed skepticism about their descriptions of China. For example, when reading “Description of the Empire of China,” he wrote, “In the eight provinces introduced by Father Du Halde, everything I saw was astonishing, beautiful, and good… Does nature really have only beauty and no ugliness?”

Montesquieu’s skepticism was not without reason and was quite insightful. The problem is that he judged China based on European customs and psychology, so his skeptical emotions often reflected his biases. In contrast, he firmly believed in various shortcomings and ugly phenomena he heard about China, such as famine, abandoned infants, and torture, and even believed in absurd claims that Chinese people sometimes resorted to cannibalism.

Because Montesquieu did not hold a completely unbiased view of China, despite having access to similar materials about China as Voltaire and others, his views on the country were quite different. He regarded China as a violent despotic state.

As is well known, Montesquieu classified political systems into three types: republican, monarchical, and despotic. The republican system is based on virtue, the monarchical system on honor, and the despotic system on terror.

The republican systems Montesquieu studied were mostly ancient city-states, which, while good, are now historical relics; the monarchical system was the best system he envisioned in reality; and the system he vehemently attacked was the despotic system he detested.

In his view, most Eastern countries practiced despotic systems, and China was no exception. He stated, “China is a despotic state, and its principle is terror.” He believed that the emperor combined both religious and secular powers, exercising brutal dictatorial rule over his subjects, leaving the people with no freedom. The emperor could arbitrarily punish officials and commoners for treason, “any excuse could be used to deprive anyone of life and exterminate any family.” He believed that China’s punishments were severe, with tortures such as boiling and lingchi being appalling, and often implicating nine generations of a family. The people lived in extreme terror, and he believed that China had a large population but insufficient arable land, leading to extreme poverty. Whenever famine struck, corpses were everywhere. Even in normal years, people were unable to support their offspring due to lack of food and clothing, leading to widespread abandonment of infants. He also believed that China had no parliament and did not implement the separation of powers, thus possessing the nature of a despotic system: “A single individual governs according to his will and capricious preferences.”

In summary, China is by no means as beautiful as the missionaries depicted, nor as ideal as Voltaire and others praised. On the contrary, “Chinese despotism, under the pressure of endless calamities, although it once wished to chain itself, has done so in vain; it has armed itself with its own chains and has become even more ferocious.”

Montesquieu affirmed that China is a despotic state, but he distinguished it from other despotic states based on the materials provided by missionaries. He wrote, “If the vast territory of the empire gives it a despotic government, then it is the best of all despotic governments.” This statement was written in his unpublished notes, quite straightforwardly. In his publicly published works, he expressed it more subtly: “Due to special circumstances, or perhaps unique circumstances, the Chinese government may not have reached the level of corruption it should have.”

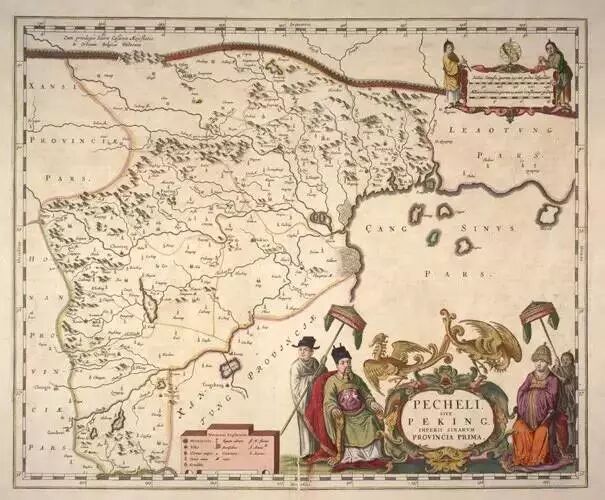

▲ A map of China drawn by missionaries

So what are these “special circumstances, or perhaps unique circumstances” in his view?

First, Montesquieu defined despotic government as one that has neither laws nor regulations, governed by a single person according to his own will and capricious nature. In another place, he stated, “Despotic states have no fundamental laws, nor any institutions to protect the laws.”

Montesquieu believed that in this regard, China’s situation was somewhat special. Although China does not have what he referred to as strict laws, especially basic laws aimed at limiting the power of the monarch, it does have moral, ceremonial, and customary practices that are effective and similar to laws.

He said, “Their customs represent their laws.”

The main goal of this law is peace, to encourage the people to work hard so that they can live peacefully. For the sake of peace, obedience must be promoted, so the relationships of ruler and subject, father and son, elder and younger, although belonging to the moral realm, have legal effect in China. If the people work hard, their livelihoods will be relatively secure; if the people can meet their basic needs, the state will also be in relative peace. He believed that this integrated law of etiquette, customs, and morality was established by ancient Chinese monarchs, effective for thousands of years, and respected by successive emperors, with the people habitually obeying it. Therefore, China is a country that is both lawless and lawful, different from other despotic states.

Second, Montesquieu believed that China’s large population and the poverty of its people meant that although the people were hardworking and the geographical and climatic conditions were relatively good, their living standards were very low, with almost no savings. Once natural disasters or man-made calamities occurred, they would be left without means of survival.

In this situation, if the rulers govern too brutally, it is easy to provoke rebellion among the people, and once a rebellion occurs, the impoverished people will respond immediately, putting the monarch at risk of losing both the empire and his life. In other despotic states, even if the governance is brutal, the people are not driven to starvation, so they are less likely to take risks and revolt.

Chinese monarchs face the constant threat of rebellion and must moderate their despotic rule to prevent unforeseen circumstances. To this end, they take measures such as: (1) not implementing the tax farming system as in Europe to avoid exploitation by tax farmers; whenever famine occurs, the emperor orders a reduction in taxes; (2) the government encourages agriculture and irrigation to increase production, ensuring that the people do not starve. The emperor even personally participates in plowing ceremonies every spring; (3) not selling official positions but selecting officials through the imperial examination system, providing opportunities for people from all social strata to become officials; (4) the court has censors whose job is to point out the monarch’s mistakes; a system of supervision is established for officials at all levels, rewarding merit and punishing faults, resulting in relatively lenient politics; (5) promoting a complete set of ethical and moral principles centered around Confucianism to mitigate the severity of laws.

Third, for similar reasons, to prevent rebellion, Chinese rulers established a system of private land ownership. This is “the reason why China has a good government and does not decline like other Asian countries.”

▲ The Chinese emperor on a royal tour

Fourth, Montesquieu believed that due to climatic influences, the Chinese tended towards servility, so the ethical concepts centered around filial piety and brotherly love have long been deeply rooted in China. Rulers apply the concept of filial piety to politics, requiring the people to respect the monarch as a father, while the monarch treats the people as children; the entire country lives like relatives in a big family. Montesquieu stated, “The composition of this empire is based on the idea of family governance.” Because this ethical concept is deeply ingrained in people’s hearts and implemented in practical life, the relationship between rulers and the ruled is less confrontational, making China’s despotic system appear more lenient than that of other despotic states.

Although China possesses many factors that are not characteristic of despotic systems, Montesquieu did not change his fundamental view of China’s political system. He could affirm certain practices in specific issues, but he remained unwavering in his assessment of the nature of the political system.

At that time, many believed that China’s long history, developed culture, relative stability, and good political system were important reasons for its success. Montesquieu had considerable disagreement with this view. He believed that China’s longevity and cultural development were purely due to geographical conditions; the boundaries of China are either the sea or high mountains and deserts, and external enemies can only invade from the north, thus ensuring relative safety.

He further deduced that if European countries had such advantageous conditions, their histories would certainly be longer than that of China. As for why China has maintained a unified situation for a long time, despite experiencing divisions, it quickly returns to unity, Montesquieu believed this was mainly due to geographical reasons. First, the Yangtze River serves as a natural barrier, dividing the country into northern and southern parts. Due to climatic reasons, northern people are fierce and warlike, while southern people are gentle and timid; once northern people cross the Yangtze River, they can quickly control the entire country without prolonged battles. Southern people are accustomed to obeying orders, making it difficult for them to form divisions. Second, China frequently experiences famine, and when one province lacks grain, it is difficult for other provinces to survive without assistance, so all provinces rely on each other and lack relative independence. The long-term maintenance of unity is also benefited by this.

It is not difficult to see that Montesquieu indeed recognized and acknowledged many merits of China, and that its political system possesses some advantages that despotic systems should not and do not have. However, he always explained these advantages through geographical and climatic factors, even though these explanations are not always persuasive. The conclusion that China is a despotic state remained unshaken in his writings.

Montesquieu’s observations and studies of China were certainly not limited to its political system. He also discussed China’s history, philosophy, religion, population, and more, with some insights. Due to space limitations, this article can only briefly touch on these aspects.

03

In evaluating China, why did Montesquieu differ sharply from most of his contemporaries among the Enlightenment thinkers? Some scholars have explored this issue. The Frenchman Carcassonne pointed out as early as the 1920s that Montesquieu’s differing views on China from Voltaire and others stemmed from his reading of travelogues written by merchants and diplomats; the authors of these travelogues either skimmed through China without in-depth investigation or harbored hostility towards China, exaggerating its shortcomings, which did not reflect the true nature of the country. The China that Montesquieu learned about from these books was naturally different from the China in the minds of Voltaire and others. This view has gained some scholarly support.

We believe this perspective is reasonable. These travelogues indeed influenced Montesquieu’s views on China. Moreover, we also believe that his negative impressions of China stem not only from these travelogues but also from his only direct contact with a Chinese person, Huang.

What Huang conveyed to Montesquieu about China was far from beautiful. Huang stated that Chinese punishments were severe, and that lingchi involved cutting the criminal into over sixty pieces, and the executioner must continue until the last piece is cut off; otherwise, the executioner would be executed. He also mentioned that when a new emperor ascended the throne, all of the late emperor’s three palaces and six courtyards would be publicly sold in the market. Such statements from a Chinese person would undoubtedly leave a profound impression on Montesquieu, making him disbelieve the various beautiful aspects described by the missionaries.

Nevertheless, we believe that the decisive factor leading Montesquieu to hold a negative attitude towards China was not merely because he read those travelogues.

Firstly, when Montesquieu began to access materials about China, he had already shown obvious skepticism, even before he had read any travelogues. The notes he made while reading “Confucius, Sinarum Philosophus” in 1713 and the notes he made after his conversation with Huang that same year can serve as evidence.

Secondly, regarding travelogues, the one that had the most significant impact on Montesquieu’s view of China was undoubtedly Anson’s “A Voyage Round the World,” which Montesquieu read with great interest; he wrote to a friend, “I am reading Lord Anson’s astonishing work… I am reading it and will read it again. In my view, this book is quite enlightening.”

This clearly shows the influence of Anson’s travelogue on Montesquieu; however, Anson’s travelogue was first published in 1749, by which time both “The Persian Letters” had been published for over twenty years and “The Spirit of the Laws” had been published for a year. This means that Montesquieu did not utilize the materials provided by Anson when writing these two masterpieces; in other words, Anson’s travelogue did not play a significant role in shaping Montesquieu’s view of China; the views we currently understand about Montesquieu’s perspective on China had already formed before Anson’s travelogue was published.

In this regard, Guasco’s recollections provide evidence: “When Anson’s travelogue was published, he (Montesquieu) exclaimed, ‘Ah, I have long said that the Chinese are not as honest as the ‘Letters Edifying and Curious’ would have us believe.'” As far as we know, Montesquieu’s use of Anson’s travelogue was limited to adding a sentence in the 1758 edition of “The Spirit of the Laws”: “I can also find the testimony of the well-known Anson.”

In contrast, Voltaire and others, who held different views from Montesquieu on the issue of China, also read such travelogues but did not accept the views of the authors. Quesnay, in his book “On the Despotism of China,” questioned Montesquieu, asking why he did not believe the missionaries who had lived in China for a long time and visited many provinces, but instead believed merchants who had only briefly stayed in China.

We know that the sections about China in “Letters Edifying and Curious” do not merely praise China. Figures like Baduoming mentioned many negative phenomena they observed in China. However, due to differing fundamental viewpoints, the conclusions drawn from the same facts can vary significantly, even completely opposite. For example, the Yongzheng Emperor executed two princes who converted to Christianity. Montesquieu wrote about this incident:

Father Baduoming’s letters describe how the emperor punished several princes for converting to Christianity, which displeased him. These letters reveal the tyranny often practiced there and the general situation of inhumanity based on established norms.

In contrast, Voltaire commented on the same incident:

The Jesuits caused the deaths of several Chinese people, especially two princes who had been kind to them, due to their conversion to Christianity. These priests came from the ends of the earth, causing discord within the Chinese royal family, leading to the execution of the two princes.

Quesnay went even further, rebutting Montesquieu, stating, “Many countries around the world have punished numerous martyrs for religious reasons… but this has nothing to do with China’s despotism.”

▲ Quesnay

In fact, the materials that people concerned about China were reading at that time mainly included “Letters Edifying and Curious” and “Description of the Empire of China,” and this was true for Voltaire, Quesnay, and Montesquieu alike. It is evident that even with completely identical materials, due to differing viewpoints of the readers, the conclusions drawn can differ, even completely opposite. Therefore, explaining Montesquieu’s aversion to China primarily based on his reading of some travelogues seems untenable.

We believe the main reason lies in Montesquieu’s ideological system and methodology.

As mentioned earlier, the theory of three political systems is one of Montesquieu’s main doctrines, which can be seen as the core of his entire theory. In his view, a country’s political system determines its other systems, such as education, justice, taxation, trade, and so on; if the political system changes, everything changes.

When Montesquieu elaborated on his political system theory, he not only used reasoning but also paid attention to finding facts from history and reality to support his arguments. As mentioned earlier, he used ancient city-states to illustrate the republican system, contemporary European feudal kingdoms to illustrate the monarchical system, and Eastern countries to illustrate the despotic system, with China being the typical example of a despotic system, which is why he devoted considerable energy to studying China.

He believed that with China’s vast territory, its political system must undoubtedly be despotic, because his political system theory asserts that “small countries are suitable for republican systems, medium-sized countries are suitable for monarchical governance, and large empires are suitable for despotic monarchs,” which is one reason.

Montesquieu also believed that a monarchical system must have a basic law to restrain the monarch and an “intermediate body”—the nobility—to play a leading role in the parliament. Since China has neither European-style nobility nor any form of parliament, it can only be classified as a despotic system, which is the second reason.

Montesquieu further believed that even with a basic law and an “intermediate body,” if there is no separation of powers to restrain power, those in power will inevitably abuse their power, causing the monarchical system to degenerate into a despotic system. The Chinese emperor holds the powers of administration, legislation, and justice, with no separation of powers whatsoever. Therefore, China can only be a despotic state, which is the third reason.

These three points are the main reasons Montesquieu could not classify China as a monarchical system and could only categorize it as a despotic system. Montesquieu’s political system theory is unscientific; there is no substantial difference between despotic and monarchical systems, and it is entirely natural for a single country to exhibit characteristics of both systems. China is such a case, and Montesquieu himself recognized this. He wrote in his notes:

China is a mixed government; it has significant characteristics of a despotic system due to the great power of the monarch;… it has elements of a monarchical system due to its fixed laws and regular courts.

However, this idea, which once flashed through his mind, was not included in his published works. The reason is that he was determined to defend his political system theory, and to do so, he had to maintain that China, like other Eastern countries, is also a despotic state; otherwise, his political system theory would appear incomplete and imperfect. He candidly wrote:

Our missionaries tell us that the vast Chinese Empire has a commendable political system, with principles of fear, honor, and virtue. Then, the distinctions I established between the principles of the three political systems would be meaningless.

He stated this so clearly and frankly that no further explanation is necessary. The conclusion is: Montesquieu, in order to establish his political system theory, despite being able to acknowledge that China has certain merits in many specific issues, maintained that China is a despotic state based on terror, and this fundamental point must not waver.

It is clear that Montesquieu’s research methods, while surpassing those of his predecessors by emphasizing the need to support theories with facts, also have evident drawbacks: he formed conclusions first and then sought, or even tailored, facts to support those conclusions. He once stated, “I have established some principles. I see that individual cases conform to these principles, as if they were derived from them; the histories of all countries are merely the results of these principles.” It is precisely because he established some principles that the “individual case” of China had to “conform to these principles,” that is, to serve the needs of establishing his political system theory.

Montesquieu’s insistence on using China as a typical example of a despotic system to establish his political system theory was certainly not a purely academic discussion detached from real politics. His political ideal was an enlightened monarchy limited by basic laws and an “intermediate body,” and his political system theory served this political ideal.

He believed that during the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV, France had already degenerated from a monarchical system to a despotic system, with the essential basic laws and “intermediate body” no longer functioning, while the inherent characteristics of despotic systems were increasingly evident in France. Therefore, in “The Persian Letters,” he mercilessly exposed and criticized various ugly phenomena in France.

“The Spirit of the Laws” made significant progress on this basis, as the author proposed methods to prevent France from degenerating into a despotic system, which was to establish an enlightened monarchical system according to his political system theory. Since the political system theory is so important, he certainly had to do his utmost to establish, perfect, and defend it. Since China was recognized as a typical despotic system, even if some facts could not prove this point, it would not matter.

Fairly speaking, Voltaire and others’ descriptions and comments on China also contain some exaggerations. This is because they infused their ideals into their praise of China, idealizing the reality of China to some extent. This does not mean that their depictions of China are fabricated out of thin air, but rather that their avoidance or embellishment of China’s shortcomings is unacceptable.

Montesquieu’s attitude towards China was cold and severe; he saw many of China’s shortcomings. However, due to his biased observations of China and his inability to carefully discern the truth of the materials he encountered, the conclusions he drew on this basis are difficult to be convincing. Nevertheless, some of his views are quite insightful. For example, he pointed out that China’s imperial examination system leads intellectuals to value literature over military affairs, resulting in national weakness and backwardness in natural sciences. He also had many incisive insights on China’s population issues. Therefore, it should be said that his research also contributed to the understanding and recognition of China by Europeans at that time.

Montesquieu’s China is not an accurate portrayal of China at that time; it and the China depicted by Voltaire and others complement each other, correcting each other’s biases. We should not shy away from acknowledging that Voltaire’s infinite admiration for China contains idealized elements, nor should we neglect Montesquieu’s research and conclusions due to his denial of contemporary China.

[The original text was published in the second issue of “French Studies” in 1985, with slight modifications]

The Academic Center of the Commercial Press has four editorial offices: Philosophy and Social Sciences, Literature and History, Politics and Law, and Economics and Management, as well as a Westlaw project team, mainly responsible for the editing and publishing of academic works in the fields of literature, history, philosophy, and social sciences. Publications include various academic translations and original works represented by the “Chinese Translation of World Academic Classics Series,” “Chinese Modern Academic Classics Series,” “Chinese Contemporary Academic Collection,” and “Master’s Works.”

Editor: Xiao L

Source: Sohu Culture