This article proposes a high-resolution multidirectional sensor that operates under low strain. Using a laser direct writing method, a porous graphene electrode is prepared on a PI/PDMS composite film, successfully creating a cross-shaped sensitive layer. The sensor exhibits excellent sensing performance, linear response, and repeatability. The unique sensing characteristics of the cross-shaped structure enable the sensor to achieve multidirectional sensing. When stress is applied along the stretching direction, the sensor is sensitive only to strain parallel to the stretching direction and insensitive to strain perpendicular to it. It demonstrates outstanding anisotropic sensing ability within a small strain range of 0%–20%, with a sensitivity ratio between the horizontal and vertical axes ranging from 134–248. This sensor can achieve multidirectional measurement of micro-movements, highlighting its potential applications in flexible wearable electronics.

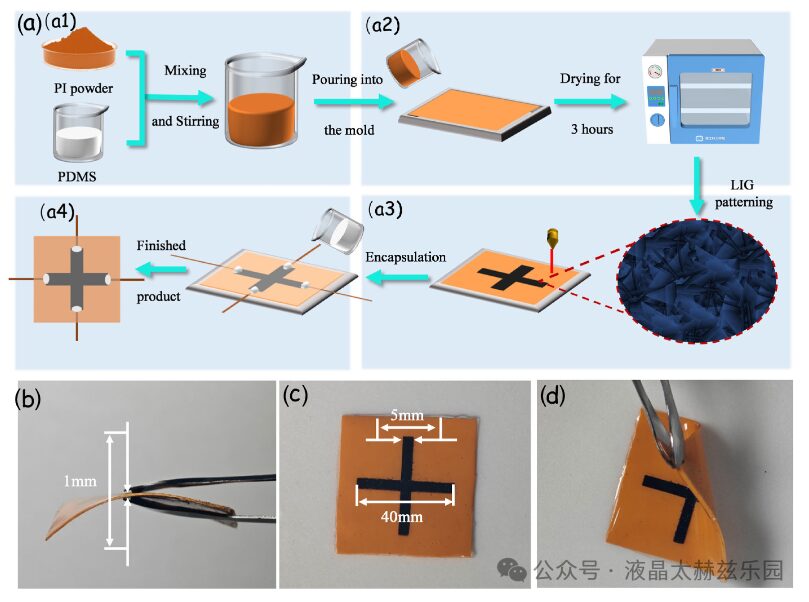

The preparation schematic of the LIG multidirectional sensor is shown in Figure 1(a). First, 3 g of PI powder, 10 g of PDMS component A (methyl vinyl silicone prepolymer), and 0.5 g of component B (methyl vinyl silicone prepolymer with vinyl side chains) are mixed in a 20:1 ratio. The mixture is stirred with a glass rod until uniformly mixed and then poured into a mold measuring 60×60×1 mm, and placed in an 80℃ oven for 3 hours to synthesize the PI/PDMS film. The film is then subjected to laser direct writing, with the laser power set to 3.9 W, laser scanning speed set to 30 mm/s, beam size approximately 150 μm, and pulse width about 50 μs. Subsequently, conductive silver paste is used to attach copper electrodes to the edges of the cross pattern. Then, a semi-cured PDMS film is bonded on top, resulting in a multidirectional flexible sensor based on the laser-etched cross structure, as shown in Figure 1(a4).

Figure 1. (a) Schematic of the preparation of the LIG multidirectional sensor. (a1) Preparation of the PI/PDMS mixed solution. (a2) Casting and molding. (a3) LIG patterning. (a4) Fixing electrodes and packaging. (b)–(d) Photos of the patterned PI film.

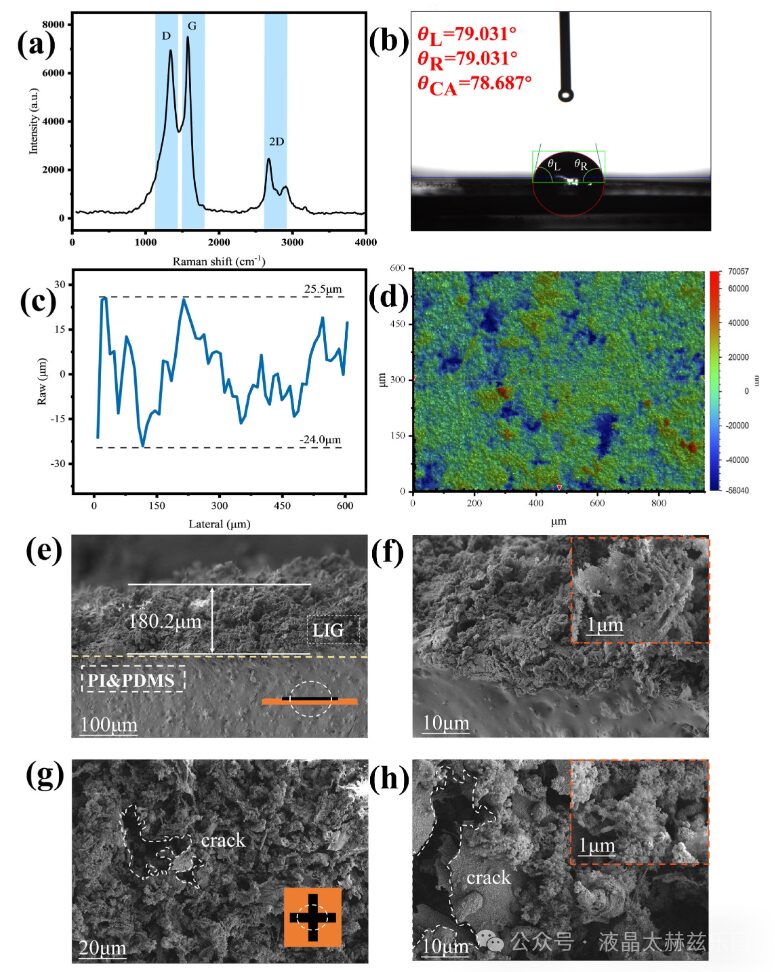

The samples obtained were subjected to SEM scanning, as shown in Figure 2(a). The Raman spectrum of the LIG sample shows two characteristic peaks at 1344 and 1569 cm−1, attributed to the D (disorder or defect carbon) peak and G (graphitic carbon) peak, respectively. The I(D)/I(G) ratio is 2.397, indicating a high degree of graphitization. The 2D peak (located at 2673 and 2917 cm−1) indicates that the sample is multilayer graphene. This is consistent with the SEM images in Figures 2(e)-(h). Figure 2(b) shows the contact angle experiment with water. The static contact angle of the LIG surface is 78.687°, indicating that the surface is hydrophilic and also indicating a high surface roughness. As shown in Figures 2(e)-(h), the SEM images depict the detailed features of the LIG surface. The surface of the LIG after laser sintering exhibits an extremely rough and irregular fluffy morphology. Figures 2(e) and (f) show SEM images of the side of the laser-induced LIG sensitive layer, where the upper layer is covered with flocculent structures of varying sizes, resulting from the uneven distribution of laser energy between graphene layers. Many tiny pores can be observed between the flocculent structures, forming a loose and porous LIG structure. This characteristic allows the sensitive layer to bond more uniformly and stably under strain conditions, forming resistance transmission channels that further enhance sensitivity and stability. The lower layer is the PI/PDMS layer, which has a relatively smooth and uniform surface.

Figure 2. (a) Raman spectrum of the LIG surface. (b) Water contact angle of LIG. (c) LIG surface roughness interference image. (d) Scanning image of LIG surface using a white light interferometer. (e) and (f) SEM images of the side of the LIG sensitive layer observed at 100, 10, and 1 μm. (g) and (h) SEM images of the upper surface of the LIG sensitive layer observed at 20, 10, and 1 μm.

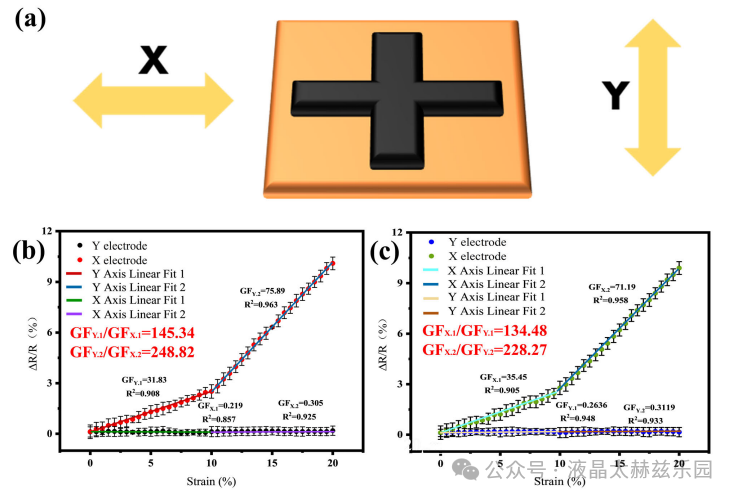

To achieve multidirectional strain sensing, the change in resistance during the stretching process of the film needs to be tested, as shown in Figure 3. For the same strain, the range of GFX/GFY is 134-248, and when different strains are applied in the x direction, the ∆R/R0 value detected by the x-direction electrode is significantly higher than that detected by the y-direction electrode [Figures 3(a)-(c)]. Similarly, when strain is applied in the y direction, a similar phenomenon occurs. The higher ∆R/R0 value in the strain direction may be related to the filling property of graphene, while the lower ∆R/R0 value in the perpendicular direction may be related to the slight shrinkage caused by the Poisson effect of PDMS.

Figure 3. (a) Schematic of the LIG multidirectional sensor. (b) and (c) Resistance changes collected from strain sensors on x and y electrodes as a function.

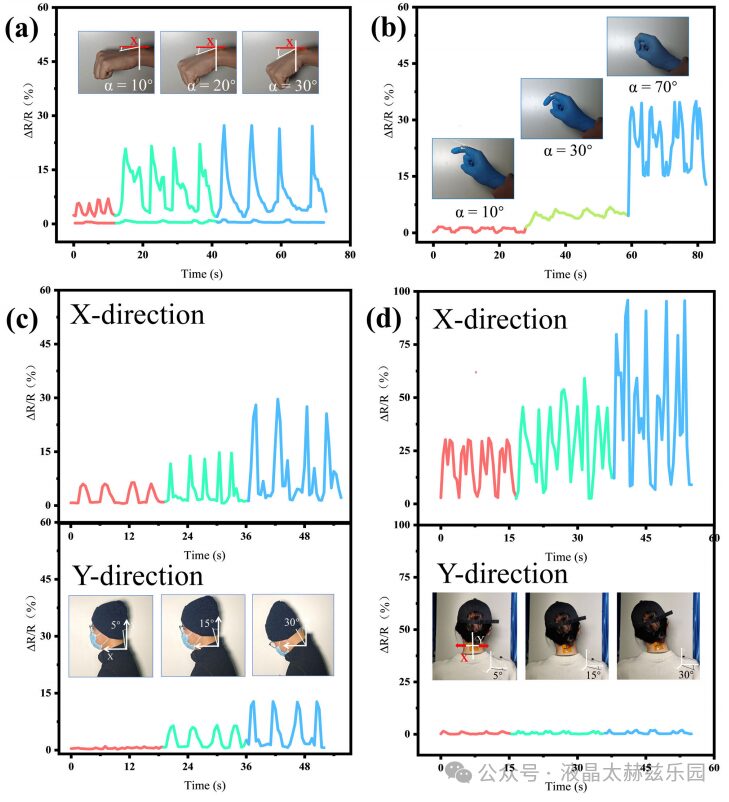

The LIG flexible strain multidirectional sensor demonstrates excellent multidirectional sensing performance, with strain range and sensitivity meeting most requirements for monitoring micro-movements in human rehabilitation. Practical applications of this sensor are shown in Figures 4(a)-(d), where it can be attached to areas such as the neck and wrist to monitor human movements. When installed on human joints, the strain sensor can effectively detect small bending movements, approximating uniaxial strain in the X direction. Small amplitude flexion of the wrist joint and slight movements of the finger joint [Figure 4(a)], as well as neck movements [Figure 4(b)]. Figures 4(c) and (d) demonstrate the sensor’s great potential in human motion detection through significant resistance response. When the head moves in the X direction, the X-axis response changes significantly, while the Y-axis response remains relatively stable, indicating unidirectional movement along the X-axis. This indicates that the sensor can identify the motion of forces in multiple directions. Similarly, when the wrist moves in the X direction, both the X-axis and Y-axis curves change. This indicates that the sensor can detect forces in multiple directions. Further analysis of the curves verifies the ability of the multidirectional flexible strain sensor to achieve multi-angle measurements, highlighting its potential in monitoring micro-movements in human motion.

Figure 4. Practical applications of the strain sensor. (a) Real-time detection of bending movements of a wrist strain sensor. (b) Real-time detection of bending movements of a finger strain sensor. (c) and (d) Real-time detection of bending movements of a neck strain sensor.

Original link: 10.1109/JSEN.2024.3483957

Source: Liquid Crystal Terahertz Paradise

▶▶ Alliance Member Recruitment | Join Hands to Create the Extraordinary!

▶▶ Alliance Council Recruitment | United Forward, Win the Future~

▶▶ A Letter to the Broad Graphene Community

▶▶ Graphene Alliance (CGIA) Long-Term Call for Papers on Xinhua Net’s “Material Strong Nation” Special Issue

▶▶ Precision Advertising Placement, Making Every Budget Worthwhile~

▶▶ Book Sharing (1) | Feel Their Persistence, Passion, Fearlessness, and Loneliness Along the Way…

▶▶ Book Sharing (2) | Let You See the Significance of Persistence, Feel the Magnificence of Not Dwelling on the Past and Not Fearing the Future~

▶▶ Book Sharing (3) | Telling You, Entrepreneurship is a Way of Life, a Romantic Journey~

▶▶ Book Sharing (4) | Please, for Him, for Them, Let Your Hands Dance, May Our Dreams Never Fall Short~

Our Video Account

“Graphene Alliance” Video Account contains the much-anticipated “X” material, exciting talks from big names, engaging and interesting science popularization videos, and even irregular “benefits” popping in… Welcome everyone to scan to follow our video account, and gather a wealth of valuable content~

Our Video Account