Currently, researchers both domestically and internationally have designed various underwater robots to assist in fishery production based on different fishery models and production characteristics. These robots can be mainly categorized into three types based on their functions: environmental monitoring and aquatic animal behavior observation robots, aquatic animal identification and capture robots, and aquatic animal habitat maintenance robots. The following discusses the application status of these three types of underwater robots in marine and freshwater fisheries according to their operational types.

Environmental Monitoring and Aquatic Animal Behavior Observation

The temperature, turbidity, dissolved oxygen (DO), pH value, non-ionized ammonia (NH3), nitrite concentration, and other environmental factors in aquaculture water bodies are key evaluation factors for water quality, significantly affecting the normal metabolism of aquatic animals. Therefore, real-time monitoring of these water quality evaluation factors is essential, and timely adjustments should be made when necessary. Additionally, the behavior of aquatic animals is closely related to environmental conditions, and tracking and observing their behavior is also an important observation aspect in fisheries. Traditional underwater observations in fisheries require divers to enter the water. When the water depth exceeds 20m, divers may experience discomfort such as chest tightness and dizziness, and prolonged exposure poses a risk of decompression sickness.Currently, the commonly used environmental monitoring method is the buoy online monitoring method, which can only measure water quality parameters at limited fixed points and is inconvenient for dynamic monitoring of water bodies in three-dimensional space. Using underwater robots can effectively solve this problem.

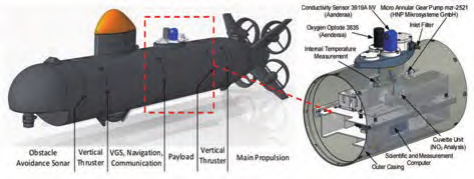

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) generally have a large size and minimum turning radius, making them suitable for deep-sea fishery environments. Researchers worldwide have used AUV to study aquatic animals and their habitats in deep-sea environments. Some researchers have used the REMUS-100 remote environmental monitoring AUV developed by Hydroid, Inc. and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) to track and monitor leatherback turtles and basking sharks using electronic tags, and obtained behavioral and habitat information of aquatic animals based on the sensor and video stream data from REMUS-100. However, the effective payload (sensor component weight) of this AUV is relatively small.Eichhorn et al. used the CWolf AUV developed by the Fraunhofer Society to carry modular water quality sensor components (Figure 2) to conduct real-time monitoring of water quality parameters in the waters near eastern Norway’s fishing grounds. The effective payload of CWolf reaches 15kg, but its body weight is 135kg, requiring at least 3 people to cooperate for deployment.

Figure 1 REMUS-100 Autonomous Underwater Vehicle

Figure 2 CWolf Autonomous Underwater Vehicle and Sensor Components

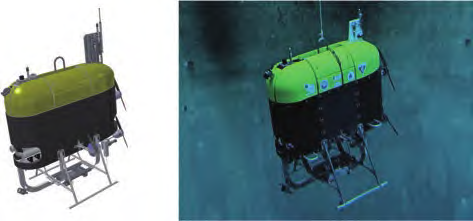

Most AUVs cause significant disturbances to the environment and aquatic animals due to their propeller thrusters, rudders, or electronic tags when conducting fishery environmental monitoring. The Mesobot underwater robot developed by WHOI‘s Yoerger et al. (Figure 3) is equipped with a large diameter, low-speed propeller, which minimizes its disturbance to the water body. The marine detection sensor components it carries can monitor the environment in the “twilight zone” of the ocean (depths between 200 and 1000m), and the Mesobot robot can also track and monitor slowly moving aquatic animals (Figure 4). Additionally, researchers from the University of Tokyo, led by Maki, developed an AUV that uses multi-beam imaging sonar to track aquatic animals, eliminating the need for electronic tags that could affect the animals.

Figure 3 3D Model of Mesobot and Its Underwater State

Figure 4 Mesobot Tracking Aquatic Animals

Figure 5 AMOUR V Developed by MIT

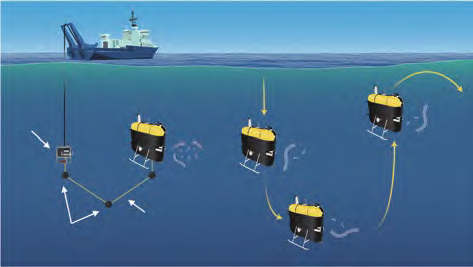

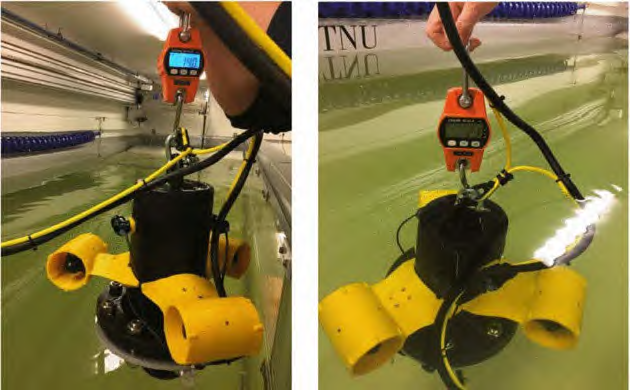

Remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROV) are suitable for near-shore fishery environments and structured, industrialized freshwater fishery environments. The computer and artificial intelligence laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a cylindrical ROV—AMOURV (Figure 5) for near-shore and freshwater fishery environments. The AMOURV achieves hovering by adjusting the balance between buoyancy and total weight, with an effective payload range of 0 to 1kg. To address the issue of large water bodies and high stocking densities (often exceeding 200,000 fish) in near-shore net cage farming, researchers from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) developed a low-cost ROV (Figure 6) that uses three small propeller thrusters to achieve lateral movement, forward and backward motion, and yaw, providing multi-factor perception of the underwater environment in near-shore fisheries. Huang et al. developed a ROV suitable for environments with water depths of 4 to 5m, specifically for freshwater fishery environment monitoring.

Figure 6 Underwater Robot from NTNU

Figure 7 Aquatic Environment Monitoring ROV from Northwest A&F University

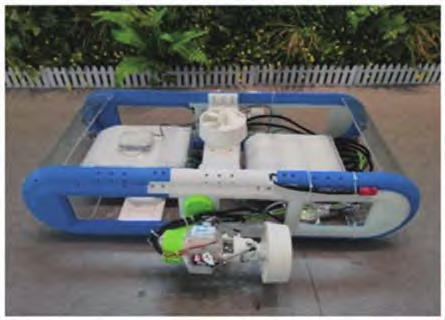

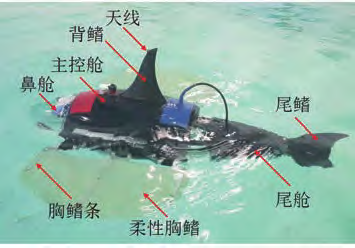

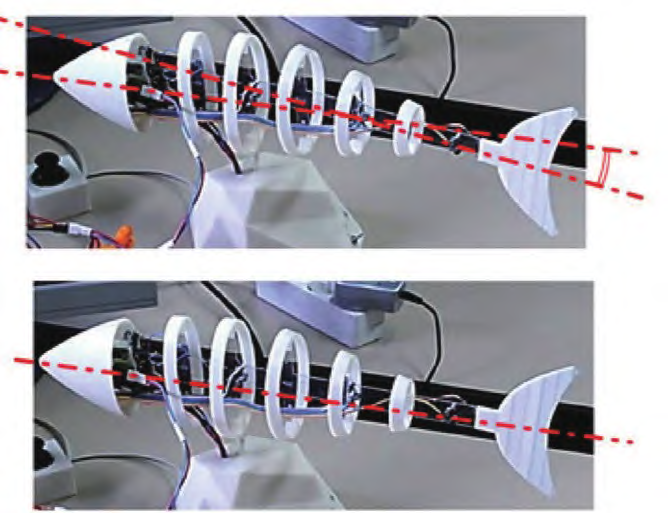

Considering the issue of AUVs and ROVs startling aquatic animals, some researchers have developed underwater robots specifically designed for environmental surveys and aquatic animal monitoring, featuring biomimetic shapes or based on biomimetic movement mechanisms. Figure 8 shows the bionic underwater robot BUV developed by the Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CASIA), which serves water ecological environment construction and can hover at specific points to monitor multiple water quality parameters. Figure 9 shows the first-generation amphibious environmental monitoring BUV named AQUA designed by McGill University, which achieves underwater propulsion through the flapping of six flat fins. Figure 10 shows the soft robotic fish SoFi designed by MIT, which is controlled by an acoustic communication module and is equipped with a fisheye camera at its head to observe fish at depths ranging from 0 to 18m without causing disturbance. SoFi has been used to track fish near the Pacific coral reefs.

Figure 8 Bionic Underwater Robot Developed by CASIA

Figure 9 AQUA Amphibious Monitoring Robot

Figure 10 3D Model of SoFi Soft Robotic Fish

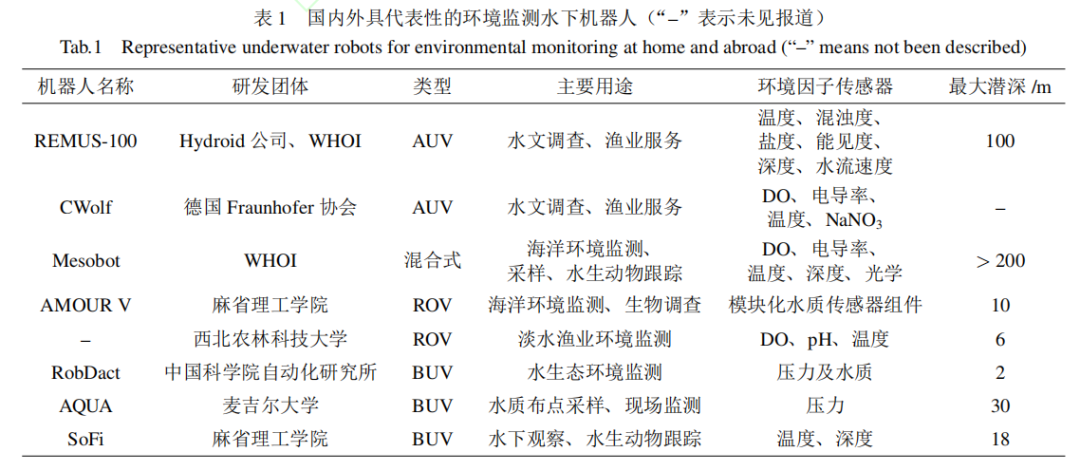

Table 1 summarizes representative underwater robots used for environmental monitoring both domestically and internationally.

In addition to directly monitoring water quality parameters and observing aquatic animals, researchers have also developed a class of robots sensitive to specific water quality parameters. These robots mimic the stress responses of aquatic animals to certain abnormal environmental factors to indirectly reflect the deterioration of water quality. Researchers from the University of Florence and the Polytechnic University of Madrid, including Ravalli and Rossi, jointly developed an underwater robot sensitive to hydrogen ion (H+) concentration specifically for aquaculture sites (Figure 11). This robot uses shape memory alloy (SMA) actuators to drive flexible structures, converting chemical signals of water quality abnormalities into electrical signals that drive the robot’s movement, capturing changes in pH levels in the aquaculture environment through different movement patterns. Changes in fish behavior are closely related to the aquaculture environment and can serve as a basis for water quality monitoring, allowing for the design of underwater robots that can act as early warning systems for abnormal aquaculture water quality, thus achieving intelligent management of fish farms.

Figure 11 Hydrogen Ion (H+) Sensitive Underwater Robot

Overall, using various underwater robots equipped with various water quality and image sensors to observe the environment and aquatic animals is a research hotspot for the application of underwater robots in fisheries, with many prototypes available. However, there are still relatively few underwater robots with high intelligence that can be practically applied, making it difficult to balance the high technicality of precise underwater environmental sensing with the economic feasibility of large-scale applications. This is a significant reason restricting the widespread application of environmental monitoring underwater robots.

Visual Recognition and Capture of Aquatic Animals

In traditional fishery production, manual diving is commonly used to collect precious marine products such as abalone, sea cucumbers, and sea urchins. To prevent the depletion of fishery resources, it is often necessary to manually measure the size of captured aquatic animals for size grading and selective release. Researchers both domestically and internationally have attempted to use underwater robots equipped with visual systems and robotic arms to replace manual labor in identifying and capturing aquatic animals.

2.2.1 Current Status of Underwater Visual Systems in Capture

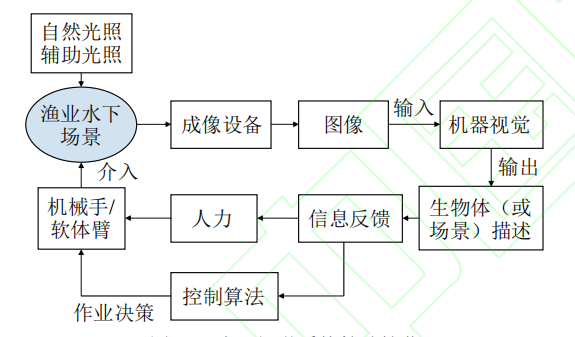

The underwater visual system extracts image information or descriptive information through image recognition, pattern classification, semantic segmentation, and scene analysis, providing feedback to humans or machines, which then use human intelligence or control algorithms to drive the robotic arm or soft arm to intervene in fishery scenarios, including capturing aquatic animals (Figure 12).

Figure 12 Underwater Visual System Assisting Capture

According to the control methods of the robots, the development of underwater visual systems for identifying and capturing aquatic animals has mainly gone through three stages: (1) Open-loop control visual feedback systems that achieve capture based on static images; (2) Visual servo control systems based on continuous feedback of visual information; (3) Intelligent visual control systems with self-learning capabilities for autonomous detection, tracking, and capture.

The underwater visual system in the first stage obtains size and location information of aquatic animals through underwater cameras and feeds it back to the control system, driving the robotic arm in an open-loop control manner or through manual operation to capture the target. Researchers from Iwate University in Japan, including Takagi, designed an underwater robot to calculate the size of abalone, providing size data to fishermen for capture and release decisions. Researchers from Kyushu Institute of Technology, including Ahn, obtained the location information of aquatic animals through underwater robots and fed it back to operators to remotely control robotic arms for target capture. Underwater robots based on this visual system have a low degree of automation in capture, requiring human intervention during the capture process and unable to autonomously capture moving targets.

The underwater visual system in the second stage can continuously and in real-time feed back information on aquatic animal species, sizes, and locations obtained from various image processing algorithms to the control system. Before operation, the parameters of the visual system need to be calibrated, and during operation, the robotic arm is driven to capture targets using visual servo methods combined with inverse kinematics solving methods based on the system’s dynamic model. This stage’s visual servo system is mainly a hand-eye system (hand-eye system), where the camera moves with the robotic arm, referred to as the “eye-in-hand” hand-eye system. The sea cucumber capture robot developed by Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics is based on the “eye-in-hand” hand-eye system. When the camera is fixed to the robot body, it is referred to as the “eye-to-hand” hand-eye system, such as the ROV developed by Harbin Engineering University, which is used for marine aquaculture and can actively suck in underwater targets. Underwater robots based on this visual system mainly identify and detect known existing targets, and in practical applications, they still require searching and tracking of targets to approach fully automated machine capture. Combining visual systems with autonomous learning methods such as deep reinforcement learning and inverse reinforcement learning is a popular academic research direction in robot learning.

The underwater visual system in the third stage has self-learning capabilities, allowing it to obtain information about the surrounding underwater environment and target status during the robot’s movement to assist the control system in real-time control, which is the future direction of intelligent capture development. Currently, there are few reports of underwater capture robots that have reached the third stage of underwater visual systems. Large-scale capture of aquatic products or aquatic products over a wide area is often conducted using trawling methods. The underwater visual system also has auxiliary applications in trawling capture, with researchers using underwater machine vision technology to improve trawling design for squid’s jetting behavior.

Currently, the main application level of underwater visual systems in fishery scenarios is still as a means to extend human visual capabilities. Most underwater robots based on artificial intelligence visual systems are still in the simulation stage on secondary development platforms such as the Robot Operating System (ROS), and practical applications require balancing environmental, hardware conditions, and system stability.

2.2.2 Current Status of Aquatic Animal Capture Robots

Modern electromechanical systems primarily target fish and benthic marine products for capture. The capture of fish mainly uses trawling methods, while existing underwater capture robots primarily target high-value marine products and scientific exploration organisms.

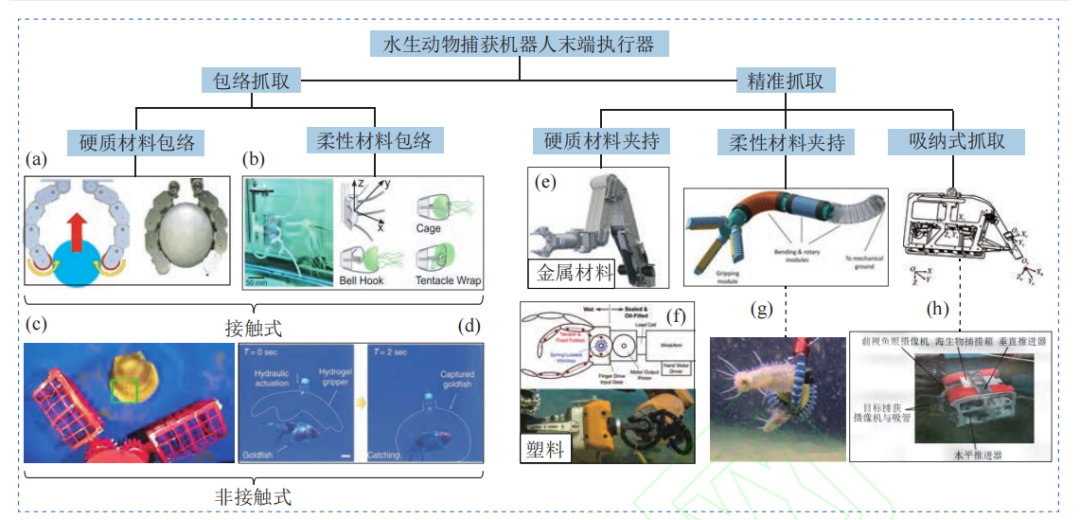

Figure 13 Current Status of Aquatic Animal Capture Robots

According to the action forms of underwater robot end effectors capturing aquatic animals, capture methods can be divided into enveloping grasping and precise gripping. Combining the different power sources and materials of end effectors, the exploratory capture methods already applied in fishery scenarios include: (1) Using open chains (Figure 13(a)), deformable continuous bodies (Figure 13(b)), net cage structures (Figure 13(c)), and container-like structures (Figure 13(d)) to achieve contact or non-contact enveloping; (2) Using motors to drive metal materials (Figure 13(e)) or plastic (Figure 13(f)) with high compressive strength to grip aquatic animals; (3) Using hydraulic or pneumatic drives with flexible materials to achieve enveloping and gripping of aquatic animals (Figure 13(g)); (4) Creating pressure differences using hydraulic or pneumatic pumps to achieve suction of aquatic animals (Figure 13(h)).

Most underwater robots used for capturing aquatic animals employ rigid structures based on gears, hinges, linkages, claws, and tweezers to grasp targets. In recent years, researchers have developed flexible grippers for capturing aquatic animals, using flexible materials to reduce or eliminate damage to aquatic animals during the capture process. Literature [27] reported a flexible gripper for near-shore fishery environments, which can achieve efficient and non-destructive precise capture of marine products when installed on an ROV. However, the repeat positioning accuracy and robustness of the flexible gripper’s grasping action may decrease, and the coupling relationship between the flexible gripper and the underwater robot body becomes exceptionally complex in underwater environments, making it challenging to perform kinematic inverse solutions based on target positions. Additionally, the flexibility of flexible grippers often comes at the cost of payload capacity. Improving the reliability and payload capacity of flexible grippers is one of the research hotspots for achieving the capture of fragile targets in the future.

In addition to developing flexible grippers, some researchers have integrated tactile feedback sensors such as force/torque sensors and slip sensors into the gripping actuators of rigid robotic arms, or current/voltage feedback units to prevent excessive gripping force from harming target animals. Developing low-inertia, adaptive robotic arms with active compliance (gripping force control) and passive compliance is an important method to meet the demand for non-destructive capture of aquatic animals.

Compared to industrial robots, the most significant characteristic of the objects of robotic operations in fishery scenarios is their reactive swimming movements to surrounding stimuli. Therefore, most underwater capture robots are only suitable for capturing slowly moving benthic aquatic products and primarily focus on high-value marine products or scientific exploration of aquatic animals.

Maintenance of Aquatic Animal Habitats

In recent years, marine net cage farming has developed rapidly. As of 2019, there were 19,400 marine net cages in China. However, the netting of cages, due to its porous and large surface area, is particularly suitable for the attachment of fouling organisms such as algae and barnacles. If not removed in a timely manner, it will affect water exchange and lead to a decline in fishery resource quality. In industrialized recirculating aquaculture, sediment such as leftover feed and solid waste from fish can dissolve in water, increasing the ammonia nitrogen content in the aquaculture environment and deteriorating the habitat. Therefore, regular maintenance of the aquatic animal habitat is an important measure to improve the quality of aquatic products. Additionally, netting inspection, patching, and lifting are also important aspects of maintaining the aquatic animal habitat.

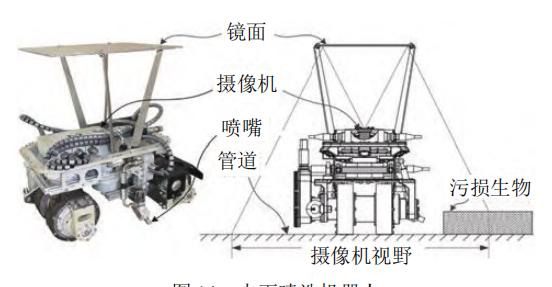

Compared to fishery environmental monitoring robots, aquatic animal behavior observation robots, and identification and capture robots, research on underwater robots for maintaining aquatic animal habitats is relatively scarce. Some researchers have addressed the lack of highly autonomous underwater robots for fishery environmental cleaning by drafting relevant design guidelines and technical requirements for underwater robots, indicating that underwater robots for cleaning netting should be wheeled or tracked robots, and high-pressure water jets should be used for cleaning. A typical underwater wheeled robot that uses high-pressure water jets to clean fouling organisms is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14 Underwater Jet Cleaning Robot

In marine fisheries, netting inspection is an important task. Damaged netting can lead to economic losses and even serious consequences of biological invasion. For underwater robots designed for cleaning netting, research is still primarily in the theoretical design phase of the hydrodynamic models of cleaning jets and the robot body. Domestic researchers have conducted theoretical analyses of key parameters of cleaning jet nozzles for netting, providing a theoretical basis for underwater robots to use high-pressure rotating water jets for cleaning netting. To enable robots to achieve stable movement during underwater cleaning operations, domestic researchers have proposed methods for robots to adhere to net cages using triangular tracked wheels and jet backflow devices. Some researchers have conducted hydrodynamic balance analyses for underwater robots using propellers and jet water flows, while others have proposed methods for calculating hydrodynamic coefficients, providing quicker and more accurate methods for establishing complete hydrodynamic models of complex underwater cleaning robots. These studies provide a theoretical foundation for the application of underwater robots in underwater cleaning operations.

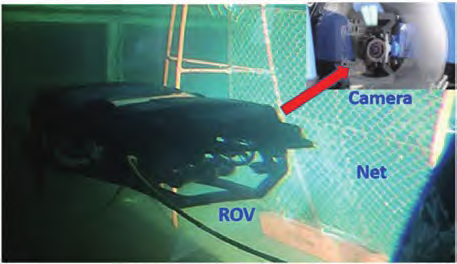

Currently, there are usable underwater robots for detecting netting fouling, capable of inspecting netting holes and pollution conditions, providing references for subsequent netting maintenance and patching (Figure 15). A commercially available and relatively mature underwater robot is the remotely operated net cleaning robot developed by Yanmar, Inc. in Japan, which can traverse and clean the netting in marine net cage farming.

Figure 15 Netting Inspection ROV

For industrialized recirculating aquaculture, cleaning methods often use cleaning brushes for contact cleaning while using pumps to suck out wastewater. Related robots are mostly in the experimental development stage. Koyama et al. developed a lightweight, tetherless autonomous underwater robot for removing sediment from the bottoms of land-based aquaculture tanks, equipped with a suction propeller at the front to suck sediment into a collection tank, with a pre-programmed movement path. Hu Yongbing et al. designed a fish pond cleaning robot that achieves an average cleaning area coverage rate of over 85% through internal spiral path planning. Mahmud et al. designed a tank cleaning robot based on route map algorithms, effectively improving the efficiency and autonomy of cleaning the bottoms of tanks. Regarding the maintenance of fishery environments in natural lakes, China’s first underwater cleaning robot for fisheries was put into use in 2019 at the Tianyun Salmon Breeding Base in Xinjiang.

In addition to maintaining the external living environment of aquatic animals, it is also necessary to care for the aquatic animals themselves. Using underwater robots for mid-birth care of aquatic animals is an important aspect of fishery development. Norway’s Stingray Marine Solutions developed an underwater robot that uses laser beams to kill external parasites such as sea lice attached to salmon. This robot scans nearby salmon using image recognition, and when it detects sea lice attached to the salmon’s surface, it emits a laser beam to kill them, achieving good applications in Nordic fisheries.

Existing Issues

Based on the analysis of the current status of the three types of underwater robots in fisheries, there are still the following issues in the development of fishery underwater robots: (1) Excessive invasiveness to the growth environment of animals. There are still shortcomings in maneuverability, low noise, low fluid disturbance, and low disturbance to animals, making it difficult to integrate with fishery scenarios; (2) Difficulty in obtaining visual information in weak visibility conditions underwater. The application of machine vision often requires ideal conditions, typically requiring the visual system to be deployed in environments with clear water, constant light sources, and simple backgrounds, or requiring underwater robots to have good hardware resources, which are often difficult to meet in natural fishery environments; (3) Difficulties in maneuvering control. Affected by water currents and unstructured complex environments, underwater robots find it challenging to maintain stable movement and reach target areas for operations; (4) Sensors struggle to accurately obtain information on fishery production and robot pose. Under multi-factor interference, onboard internal and external sensors have not met the intelligent demands of actual fishery production.

This article is excerpted from “Current Applications and Key Technologies of Underwater Robots in Fisheries,” originally published in “Robotics”; authors: Xu Yuliang, Du Jianghui, Lei Zeyu, Cai Yuyan, Ye Zhangying, Han Zhiying; references omitted; please indicate the source of information when reprinting.