Excerpt from TechCrunch

Translated by Machine Heart

Contributors: Terrence, Wu Pan

Some choose to see the limitations of this world, which leads to a dead end. Here, we choose to see the possibilities of the world.

Looking back at the first season of ‘Westworld’, I must say that Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan’s detailed understanding of artificial intelligence is truly impressive. The fantasies, backstories, and even the idea of training other hosts as receptionists have provided real insights for actual AI research.

Building a Westworld receptionist is somewhat like assembling IKEA furniture piece by piece, but in a fantasy context—this direction is not very useful. Here are some guidelines for DIYing your own Westworld robot receptionist.

Additionally, we persuaded Dr. Daniel Klein, Chief Scientist at the AI Research Institute of Oxford University and Stanford University, to discuss how to tackle these challenges.

Step 1: Buy a Boston Dynamics Robot

Boston Dynamics’ state-of-the-art robot Atlas requires so many improvements that I wouldn’t even consider it a hoax. Atlas can walk on various uneven surfaces, open doors, and even get back up after being knocked down—but you certainly wouldn’t mistake it for a human.

The robot weighs 330 pounds and walks clumsily, so unless you just want to create a malfunctioning Sheriff Picket and call him one day, you’ll need to make some massive modifications.

For beginners, you must find a way to achieve human fine motor skills. Our face has 43 muscles that help people communicate and convey emotions in astonishing ways. Unfortunately, adding more human features can also create problems—it can make it look more terrifying (refer to the ‘Uncanny Valley’ theory).

To create a true human simulation, you must have the correct skin temperature, and you need to nail those little details, even sweat. Holding the rough, cold hand of an unrefined receptionist would ruin the entire experience in an instant. Of course, we must admit that the whole plan is quite challenging, but at least we know where the goal lies.

Step 2: Induce Intelligence

Artificial intelligence requires a vast amount of information to accomplish a single, clear task. We train our machines with data for weeks, and then they can play a game or classify spam. In contrast, even with limited information, humans can achieve more capabilities.

Imagine you burned your hand just by touching a frying pan on the stove. If your conclusion is that frying pans burn people, you might be an unsuccessful DeepMind experiment. The most obvious answer is that a pan on the stove burned you because it was heated—excessive heat can burn us. A computer might choose not to touch any frying pans again—that would be quite foolish.

Professor Klein explains that there are two main approaches to solving this problem. The first is bottom-up, while the other is top-down. Most of the work in AI today is bottom-up. We strive to do more complex things—like moving from words to sentences to complete conversations.

The other approach is to input rules and let the system figure out how to achieve the desired results on its own. We have made more progress from the bottom than from the top. Figure out how to work effectively from the top down, and you might find yourself with a seven-figure salary at a tech company.

Step 3: Look to Humans for Inspiration

Just as Bernard studies Theresa, we can gather a lot from our own species. Intelligence, whether human or artificial, requires information and goals. We can simulate the interaction between information and goals with utility.

The cost of a cappuccino in San Francisco is $5, but its utility, considering what you can do without the calories (or lack thereof), is the time you spend on coffee and your post-caffeine productivity.

From here, modeling decisions is as simple as calculating the utility of things and asking which is higher. Introduce some game theory, a bit of rational choice, and even some behavioral economics, and you will get closer to the goal of building a receptionist.

“Data, learning, memory, computation, and hard-coded goals make intelligence effective,” Professor Klein says. “This is true for both machines and humans. Human goals are short-sighted; I want to be satisfied in my life, and we make trade-offs to maximize these functions.”

Now you might start to wonder if you are also a receptionist? It’s just a thought. We strive to simulate everything, especially over longer time frames, because the world is a very complex and dynamic system—even too complex for our most sophisticated processors.

“Our systems today use brute force to crack problems,” Professor Klein says. “Humans do more meta computation, thinking about what to consider.”

Today’s cutting-edge technology uses reinforcement learning to help a computer win at Go. We capture the utility of various move strategies, eliminating inefficiencies—that’s what we want. Importantly, the hard-coded assumption in games like Go is that we want to win! This initial assumption connects well to the idea of the ‘foundation’ backstory in the show (note: referring to the foundation set for the personality of the robot receptionist in the story).

Step 4: Let Receptionists Talk to Each Other

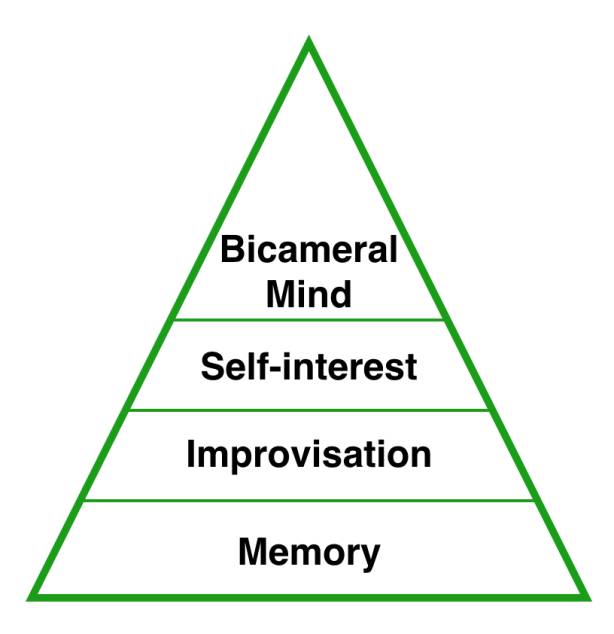

Having receptionists converse with each other during downtime is a great way to train them from a machine learning perspective. Similarly, some tech companies today use simulated training data to accelerate the training process.

Another thing to remember is that real humans constantly improvise. A receptionist that merely runs a static objective function is not very interesting. Something as adaptable as Bayesian cognition is inherently suitable for receptionists.

“We can turn data into behavior,” Professor Klein says. “The same algorithms can be terrible or great; great examples are even more numerous.”

The world exists in a series of constantly changing states, and good AI needs to be able to respond in real-time to update its preferences. Increasing the amount of input adds complexity and chaos—though these two things may sound daunting, they are quite necessary.

Step 5: Don’t Forget Reveries

Last but not least: reveries. They strip away the ideas of emergent behavior and phase transitions, which are a real challenge for researchers in the AI space.

Professor Klein explains, “If you build a set of capabilities, say A, B, and C, and add a way for them to interact, like addition (+), you can generate A + B, B + C, C + A, etc., which you couldn’t generate before.”

This can also be said to be minimal memory, which may seem like harmless gestures but can disrupt a complex system.

Bicameralism (the voice that talks to you) has been viewed as a theory of consciousness, but such voices may force the emergence of behavior, similar to reveries.

“We see the theme of the essence of viral consciousness,” Professor Klein adds, “We see the same thing with ideas; a meme is a viral idea.”

The butterfly effect explains how something as slight as a butterfly’s wing can drastically change any complex system in unforeseen ways—whether it’s ocean tides or cognition.

Good luck in building your own Westworld receptionist. And good luck to humanity, as humans are becoming increasingly less significant.

© This article is translated by Machine Heart, which is a contracted author for Toutiao. This article was first published on Toutiao, please contact this public account for authorization to reprint..

✄————————————————

Join Machine Heart (Full-time reporters/interns): [email protected]

Submissions or inquiries: [email protected]

Advertising & Business Cooperation: [email protected]