Anti-loss, elevator direct to safety islandReporter Liu YaEast A

Anti-loss, elevator direct to safety islandReporter Liu YaEast A

In space exploration, the Soviet Union set multiple records – the first to enter space, the first to launch Venus and Mars probes, etc., proving that the Soviet Union did not lack excellent engineering technology. However, why did the personal computer revolution that began in the mid-1970s not occur in the Soviet Union, but instead surged on the western side of the “Iron Curtain”? Cybernews interviewed MIT Russian technology historian Slava Gerovitch, who discussed the ideological impact of cybernetics on Soviet computer science, as well as various factors including economic activities and market demand that led to the Soviet Union falling behind in the computer revolution.

Before computers could perform functions like telephony, photography, or television, their main role was for warfare. Computers could calculate missile trajectories, the power of nuclear weapons, or the distribution of weapons in just a few hours, while traditional methods could take months. This remains a decisive advantage in overcoming the enemy.

The Soviet leaders were well aware that the British and Americans used some man-made machines for calculations. However, the Soviet official stance on cybernetics was hostile, accusing computer science of being “inhuman capitalism”. Yet privately, they were racing to develop their own computer technology.

In 1962, a senior assistant to President Kennedy warned that if the Soviet Union managed to turn the tide, “by 1970, the Soviet Union might have a whole new production technology” using “self-learning computers”, concluding that if the pace of technological advancement in the U.S. did not change, “we’re done”.

We now know that these predictions did not come true, and even today, hardly anyone can name a Soviet computer brand. The situation in the Soviet Union seems strange given that people clearly understood the benefits that computing could bring.

According to Slava Gerovitch, director of the MIT Program for Research in Mathematics, Engineering, and Science (PRIMES), the history of computer development in the Soviet Union has been tumultuous. Over the past 40 years, computers have been hesitated over, loved, and rejected here.

Gerovitch also stated, “Many people in the Soviet Union were skeptical of the government. So when cybernetics became popular and was officially approved, people began to wonder if there was something wrong with the government’s actions.”

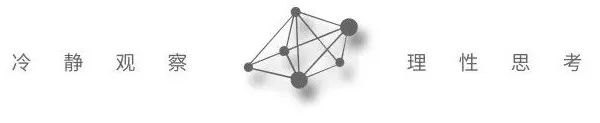

I sat down with Slava Gerovitch to discuss how ideology influenced the competition in computer technology, how Soviet computers were different, and why socialist revolutionaries did not support the digital revolution that was so advantageous to the West.

A Mera CM7209 produced in 1986 in Pripyat, Chernobyl | Image source: reddit.com

Looking back at the early Cold War, the Soviet Union’s technological capabilities seemed to be on par with the United States. These technological capabilities refer to the rapid development of the atomic bomb and advanced aviation and space exploration capabilities. So is it reasonable to assume that the Soviet Union’s early computing technology was not far behind that of the United States?

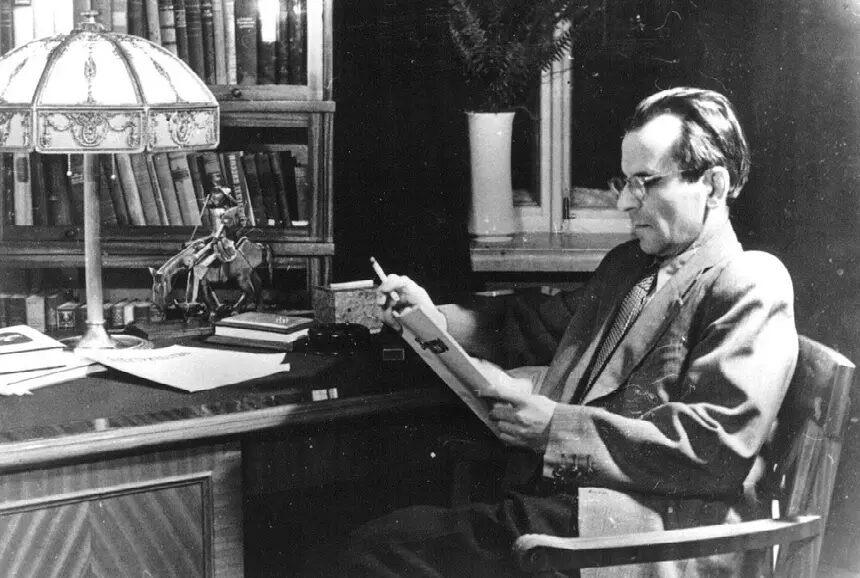

The United States produced the first electronic digital computer for atomic bomb calculations in the mid-1940s. The Soviets were aware of this and began to develop their own. Thus, the Soviet Union exhibited a clear technological lag from the start.

With the development of rocket technology, the Soviets learned a lot from German scientists, so there was some technology transfer. Of course, the Soviet side also had many original technologies, which Russia later took over and further developed.

Moreover, the process of introducing new technologies in the Soviet Union was very different from that in the United States. In the U.S., the military posed problems and set project funds, allowing capable scholars to conduct research with this funding to provide solutions. The Soviet approach was a top-down decision – assigning someone to solve the problem.

Thus, there was almost no competition. Later, with the establishment of research institutions, competition followed, even under the Soviet system. But in the 1940s, Sergey Lebedev developed the first Soviet electronic digital computer – MESM in Kyiv, based entirely on his own ideas.

The first Soviet computer (Малая Электронно-Счетная Машина, MESM) | Image source: ferra.ru

Essentially, Sergey Lebedev, as the director of the Kyiv Institute of Electrical Engineering, used personally controlled resources in developing the computer. In fact, it took a while for supporters of Soviet electronic digital computers to win the argument with supporters of analog computers and gain resources to launch large-scale projects for building electronic digital computers.

Thus, although the Soviets established a research institute for developing large computers as early as 1948, the initial control of this institute was in the hands of supporters of analog computers. In the two years following its establishment, the institute had ample resources. However, they used all these resources for analog computing. It wasn’t until 1950 that supporters of electronic digital computing won this debate.

Youdepicted a path dependency that started lagging from the beginning. Is this assumption correct? Does it mean that the Soviets were always chasing rather than leading in computing?

In a sense, yes. The Soviets were aware that the Americans and British had working machines, and they were also trying to create computers. However, they did not understand many details of Western computers. Therefore, they left a lot of room for innovation in their computer development, rather than merely imitating Western computers. This space led to interesting, tangible progress.

In your book From Newspeak to Cyber-speak, you discuss the Soviet rejection of cybernetics and how Soviet computers were viewed as “giant calculators”, while Americans saw them as “giant brains”. If there was such ideological pressure, how did it limit Soviet progress in computing?

There are two parallel developments. On one hand, Soviet electrical engineers were developing new computers for the military. This was a high-caliber activity reflecting the high priority of the defense industry, meaning the military provided the necessary resources.

On the other hand, completely unrelated to computer development, Soviet media joined the ideological movement targeting various ideological goals related to the West and American imperialism, including academic theories developed in the West, as well as cybernetics.

Cybernetics became a victim of the ideological movement of Soviet journalists, theorists, and people unrelated to actual computer development.

Engineers working on computers in the Soviet Union were well aware that they should not in any way associate their work with “contaminated” cybernetics. This led engineers to view their work merely as pure technical work. In other words, computers were essentially large calculators, not machines capable of performing thinking functions. Otherwise, they would face the danger of being associated with contaminated cybernetics.

While this helped computer engineers avoid ideological attacks, it also limited their view of computer applications. They were reluctant to connect with scientists working in various fields, who could have used computer simulations to advance their disciplines. In this early period in the early 1950s, to avoid ideological complications, the application areas of computers were very limited.

Another possibly more important factor was that computers could only be used within defense institutions. Therefore, scientists who could have used computers either were unaware of these computers or had no opportunity to use them. Overall, computer engineers were not interested in attracting users from academia.

A personal computer displayed during a parade in East Germany in 1987 | Image source: weareplanc.org

This ideological lag led to the fact that in the late 1970s, Americans witnessed a revolution in the field of personal computers, while Soviets could not keep up with the same pace of change. At that time, Americans had developed Commodore, TRS, Apple, and various other types of computers. It wasn’t until 1983 that the Soviet Union saw a similar situation. Does this mean that ideology hindered the development of computers in the Soviet Union?

After the mid-1950s, when cybernetics was reshaped, its ideological complexity beyond pure computation no longer existed. On the contrary, it was portrayed as a science of communism. At that time, associating with cybernetics became ideologically beneficial.

The 1961 Soviet Communist program mentioned cybernetics. Ideologically, using computers for symbolic processing and simulation calculations became acceptable. Naturally, scientists became very interested in using computers. From the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, this became a very popular field.

Thus, the cybernetics movement of the 1950s did not produce long-term negative effects; other factors were at play. From the early to mid-1970s, the popularity of cybernetics began to appear somewhat exaggerated, and some of its claims started to seem overly broad, while many of the promised advancements were hardly realized.

Serious scientists began to doubt those early claims about the usefulness of computers; some began to express skepticism because cybernetics had become ideologically correct. Many in the Soviet Union began to doubt the government for this reason. It can be said that when cybernetics began to gain popularity and was recognized by the government, people started to suspect that there might be problems.

Thus, cybernetics became a term associated with government-imposed, efficiency-oriented control, rather than one related to innovation and reform in science. This was particularly evident in economics, where people saw various factories using computers to control information and monitor workers’ performance more effectively.

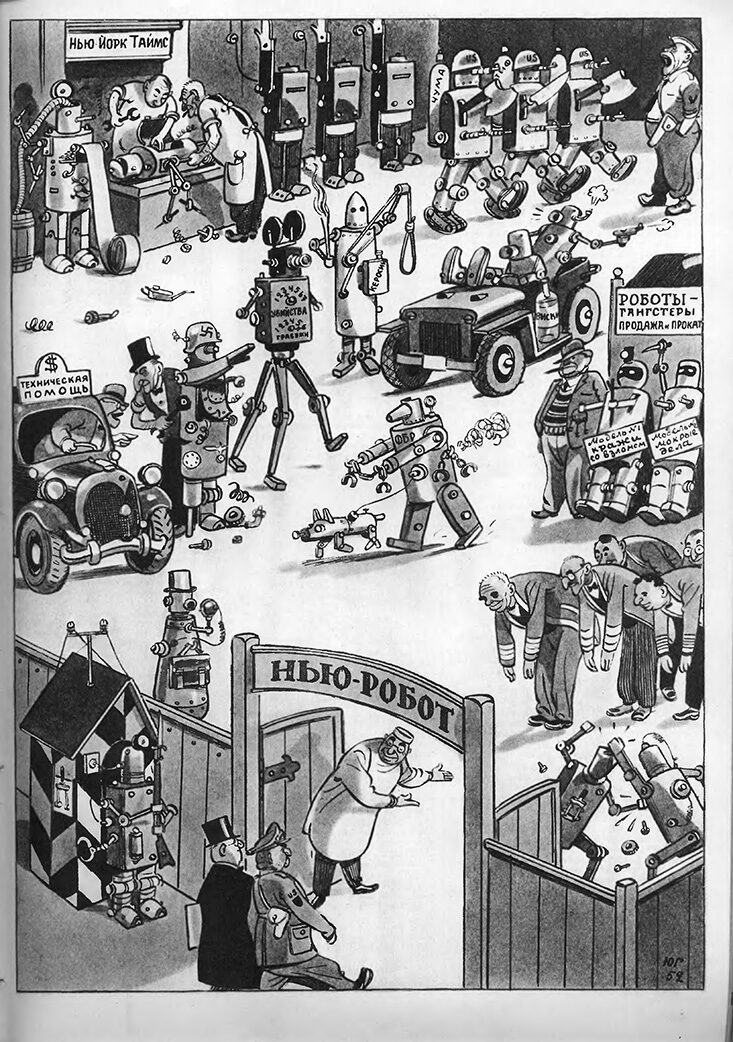

A cartoon published in the 1952 Soviet popular science magazine Tekhnika–Molodezhi, satirizing the dystopia of cybernetics. | Image source: Iulii Ganf & N. Smolianinov

And in terms of personal computers, other factors were also at play. Computers are communication devices that allow you to easily store, transmit, copy, print, and distribute information. This means that computers are a tool for autonomous communication that can operate without government control. Therefore, the Soviet government was extremely unwilling to allow personal computers into the hands of the general public.

Another issue is that personal computer manufacturing requires a consumer-oriented industry to drive it, but this was obviously not a priority for the Soviet Union. Therefore, the quality of the components produced in the Soviet Union was not high. For example, with Soviet cars: when you bought a car, the first thing you had to do was repair it.

Computers are similar; to be usable, you had to become an engineer yourself. The Western idea of developing personal computers was consumer-oriented, not requiring you to be a computer scientist or engineer. The environment for introducing personal computers was very different, and the audience was also very different.

The prototype of the home automation system Sphinx produced in the Soviet Union | Image source: reddit.com

However, by the mid-1980s, the situation did change. With reform and restructuring, the production of personal computers in the Soviet Union exploded, with some models even being exported abroad. Was this change solely related to policy changes, or did the Soviet Union improve its technological capabilities?

With reform and restructuring, government control over small economic activities became more relaxed. People could import computers from the West, and suddenly they could also resell computers from Western countries. They could buy parts from the West to assemble, or assemble their own devices with Soviet-made parts.

The reduction of restrictions on economic activities catered to the widespread demand for personal computers at that time. With the relaxation of communication controls, Soviets began to exchange emails with the outside world. The demand for communication and information processing devices increased, and both imports and local production met this demand.

However, with the general decline of Soviet industry and the early post-Soviet government stopping price subsidies, personal computer production quickly collapsed. Since then, Russia has basically relied on foreign production for personal computers.

The Agat-4 personal computer produced in the Soviet Union in 1984, almost comparable to the American Apple II. | Image source: online

You mentioned the divergence in technological development and the concept of cybernetics developing independently of Western thought. Are there any contributions from the Soviet Union to computing that are still noteworthy today? For those born after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it is easy to think that the Soviet Union had no innovations.

Soviet computer engineers and software developers had some interesting innovations. Some of these were results of the Soviets having to solve complex problems with minimal technological resources in the absence of necessary components. Thus, they sought to invent new computer architectures that might be more efficient than traditional architectures.

For example, our usual computers use binary, meaning each cell in computer memory has two states, 0 and 1. However, in the 1950s, the Soviets developed ternary machines. This required different types of programming and different types of software, but it utilized computer resources more efficiently.

Moreover, the Soviets had a tradition of efficient programming using low-level computer languages, which required many mathematical skills to design effective algorithms. Using low-level programming languages, primarily machine code and assembly language, programmers were able to use computer resources very effectively. However, using these programs, writing, debugging, etc., was a very challenging mathematical and logical task that required a lot of expertise – Soviet programmers thus became renowned worldwide. In that early phase of computer development, they were able to load efficient programs into very small computers’ memory. Due to efficient programming, the Soviets were always able to solve the problems they needed to address.

This article is translated from Why the Soviets didn’t start a PC revolution

https://cybernews.com/editorial/why-the-soviets-didnt-start-a-pc-revolution/

Notes