★

Welcome to the hard technology of Guokey.

★

From Low-Price Dumping to a Fall from Grace

Top 10 Semiconductor Manufacturers and Their Value Changes[2]

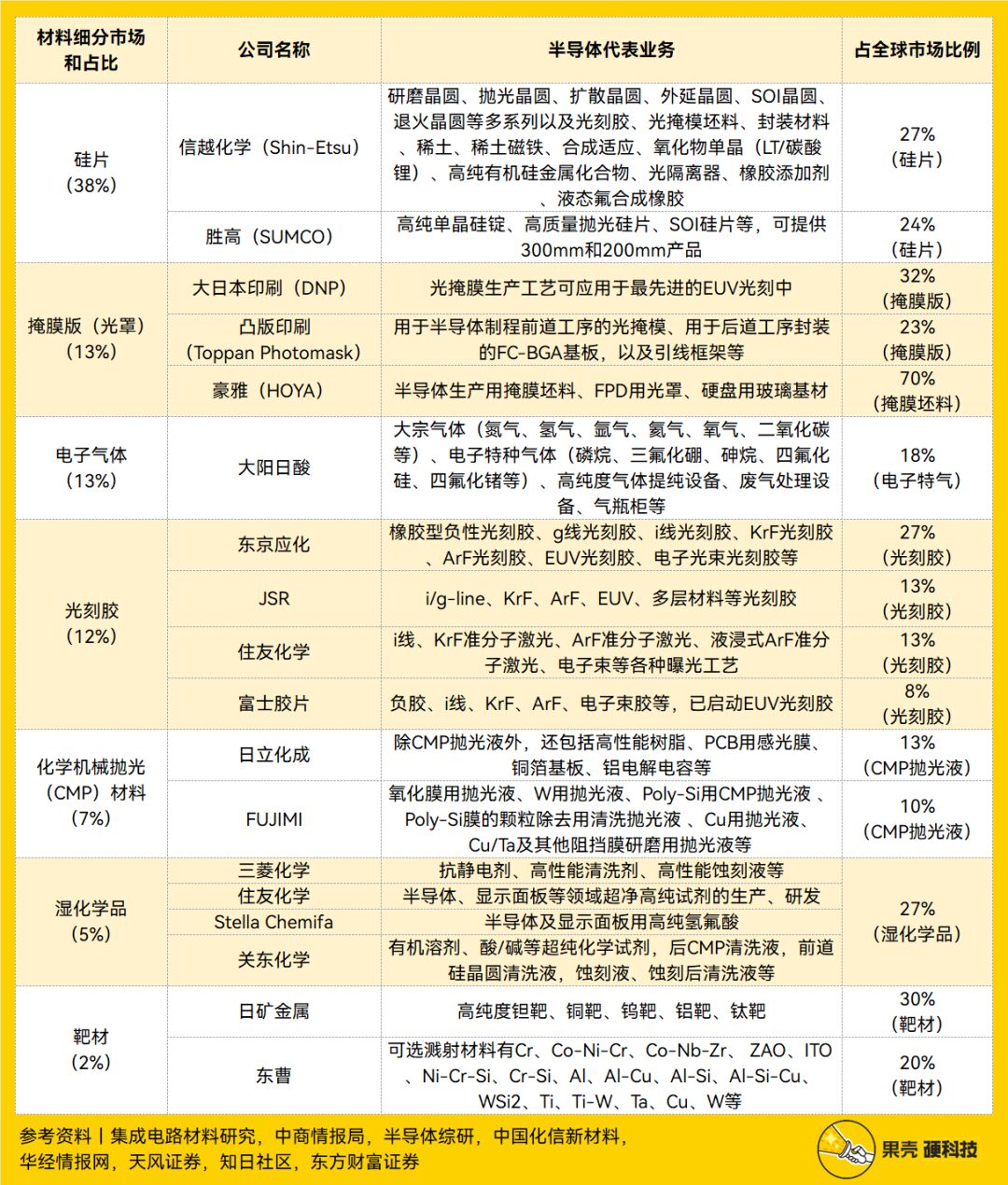

Living Off Past Glory in Materials and Equipment

The Global Semiconductor Market Pattern by Field[17]

-

Silicon wafers: High investment in production lines, high depreciation costs, volatile gross profit margins, and many long-term supply agreements (LTA). Shin-Etsu Chemical and Sumco together have maintained a market share of over 50%;[19] -

Photomasks: 45nm is a watershed; wafer fabs with processes more advanced than 45nm generally produce their own photomasks, while mature processes tend to opt for third-party photomask products for better cost. DNP, Toppan Photomask, and Hoya are three Japanese companies with significant market dominance, with SKE holding a 20.2% market share in photomasks for flat-panel displays;[20] -

Electronic special gases: These gases require extremely high purity. Taiyo Nippon Sanso holds 18% of the global market. In terms of electronic gases for semiconductor use in China, companies like Kanto Chemical, Central Glass, and Showa Denko exhibit strong dominance;[21] -

CMP materials: In CMP polishing liquids, Hitachi Chemical and Fujimi together have maintained a market share of over 20%. In CMP polishing pads, U.S. DuPont has long held over 80% market share, while Japan’s Fujibo and JSR occupy single-digit shares;[22] -

Photoresists: These are high-tech barrier materials, with complex processes and high purity requirements, and a certification cycle of 2-3 years. Tokyo Ohka Kogyo, JSR, Fujifilm, Shin-Etsu Chemical, and Sumitomo Chemical are mainstream manufacturers, and currently, only Japanese companies can produce EUV photoresists besides U.S. DuPont;[23] -

Wet chemicals: These are used in various downstream applications, have high technical barriers, rapid updates, strong functionality, and strong added value. Japanese companies hold 27% of the global market share, including Kanto Chemical, Mitsubishi Chemical, Kyoto Chemical, and Sumitomo Chemical;[24] -

Target materials: Among all industries, the target materials for semiconductors have the highest purity requirements. Nippon Mining’s market share reaches 30%, while Tosoh’s market share is 20%. In 2021, Japan’s target materials accounted for 16% of the semiconductor capacity in mainland China.[25]

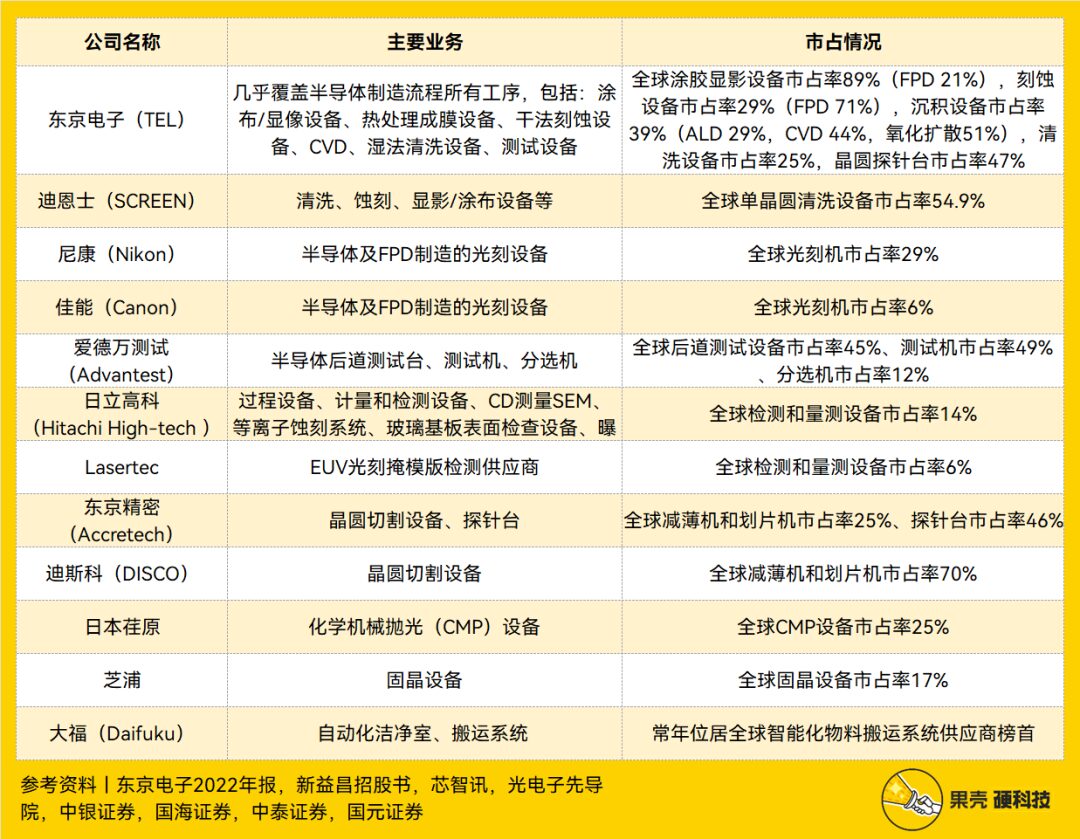

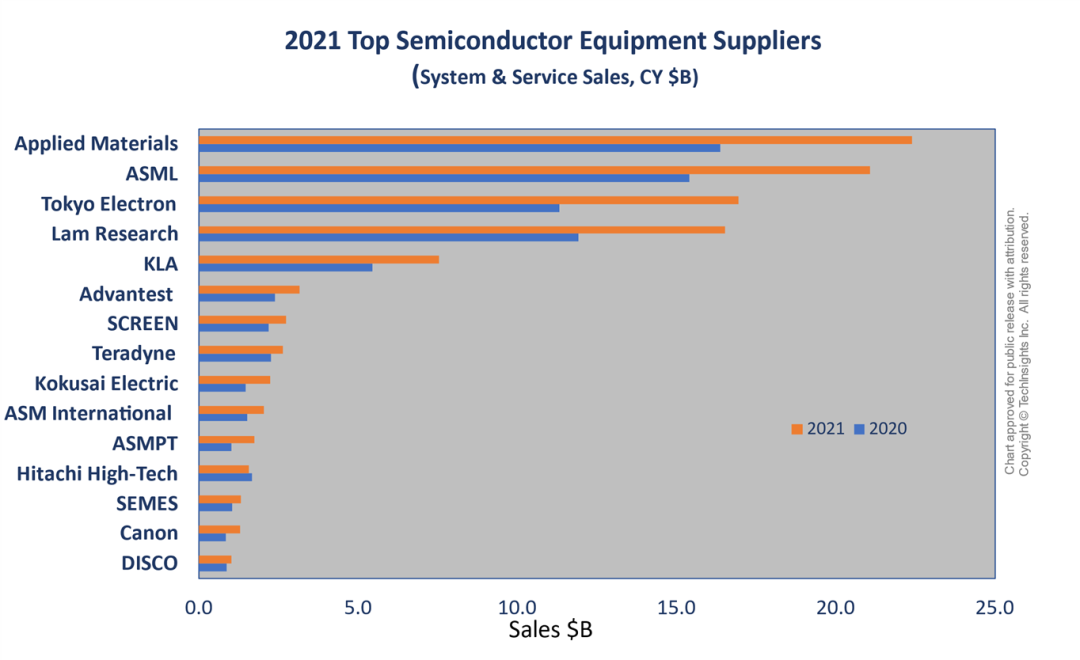

Top 15 Semiconductor Equipment Suppliers in 2021[49]

Major IC Companies in Japan, Table compiled by Guokey Hard Technology

Domestic Chips Should Not Follow Japan’s Old Path

Japan’s semiconductor industry, now in the shadows, will find it challenging to regain its former glory. Experts analyze that, given Japan’s current development situation, returning to the level of the 1980s would require an investment of at least $78 billion to make up for more than 20 years of investment shortfalls, and there is no other way out.[55]

However, contrary to this, Japanese companies have always been very conservative, especially in semiconductors. Many companies have experienced severe failures, so even when receiving a large number of orders, they are reluctant to expand production, instead pursuing the goal of becoming “small and beautiful” companies.[56]

With the current downward trend in overall semiconductor demand, Japanese companies’ advantages in equipment and materials have begun to gradually weaken, and relying solely on past glories is no longer feasible. The Semiconductor Equipment Association of Japan (SEAJ) data shows that as of February 2023, Japan’s semiconductor equipment sales have declined for five consecutive months, and SEAJ predicts that Japan’s semiconductor equipment sales will drop to nearly 3.5 trillion yen this year, a decline of 5%, marking the first decline in four years.[57]

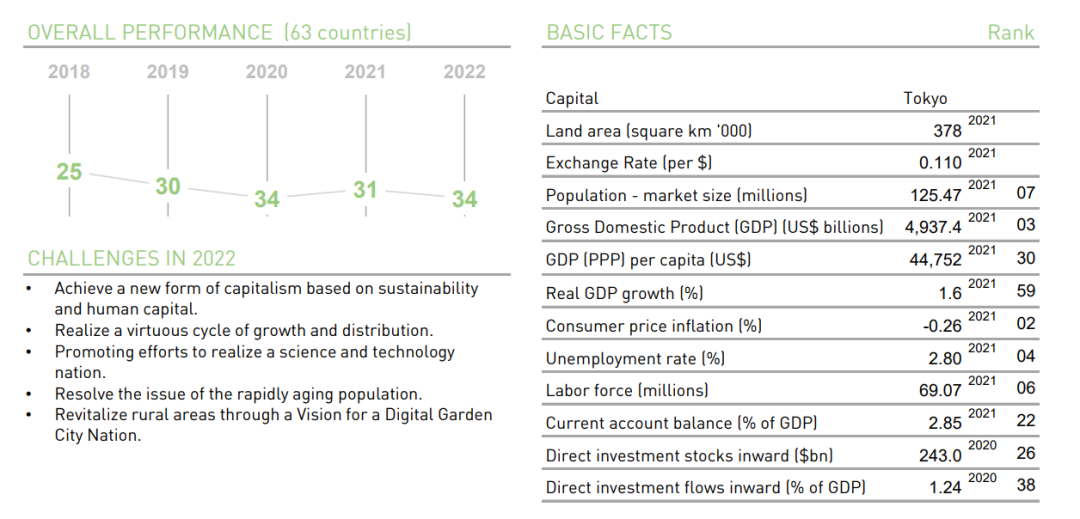

Moreover, the operational efficiency of Japanese companies has gradually declined. In the 2022 IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook, Japan’s overall competitiveness dropped from 25th in 2018 to 34th (out of 63 countries and regions). Over the past 20 years, Japanese companies’ rankings in international competitiveness have fallen from the 20s to the 30s, with operational efficiency indicators all ranking below 40.[58]

Japan’s World Competitiveness Related Data[58]

In fact, Japan’s past predicament is very similar to that of domestic semiconductors: a short-term rise followed by unreasonable suppression by the U.S. Although we cannot avoid foreign restrictions from the source, we can learn from the experience:

-

Japan lacked sensitivity to changes in production models, stubbornly adhering to a vertical production model in R&D and production, making it difficult to meet market demand. Over time, the market eliminated these Japanese products;[59]

-

Japan failed to seize market trends, not only neglecting the importance of microprocessors (CPUs), cellular mobile technology, and smartphones but also facing bottlenecks in the Japanese-style technology supremacy, leading to an increasing inability of Japanese companies to keep pace with market developments;[9]

-

Japan’s industrial chain system lacks resilience, with insufficient high-end process manufacturing capabilities, only able to produce low-end products at 40nm, creating a duality paradox with upstream competitive advantages;[3]

-

Development through closed-door methods cannot produce advanced technology; only “bringing in and going out” can enhance competitiveness;

-

The clause in the U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Agreement stating that “foreign products must account for 20% of the Japanese market share” became a lethal weapon for the U.S., continually demanding Japan to open its market, and China should also take this as a warning, recognizing the harm of related clauses and remaining vigilant against U.S. schemes.[59]

Regardless, Japan’s days of living off past glories are long gone, and domestic semiconductors should seek new strategies.

References:

[1] Kyodo News: The Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry said that Japan will provide an additional 260 billion yen to Rapidus. 2023.4.25. https://china.kyodonews.net/news/2023/04/8ca5b5425686-rapidus2600.html

[2] Liu Xuan, Ji Yaqi. The Diversion of Japan’s Industry and the Decline of Its Semiconductor Industry in the Post-U.S.-Japan Trade Friction Era [J]. Modern Japanese Economy, 2021, (02): 18-30.

[3] Xu Bo, Wang Lei. Rethinking the Upgrade of Japan’s Semiconductor Industry Chain: Three Key Points, Dual Paradoxes, and Political Tools [J]. Journal of Japanese Studies, 2022, (06): 104-124 + 151.

[4] Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences: The Past, Present, and Future of Information Technology. 2013.9.22. http://www.ime.cas.cn/jgsz/kybm/icac/learning/learning_2/201811/t20181121_5190667.html

[5] Gelonghui: The Semiconductor “Three Kingdoms Kill” Between Japan and South Korea. 2018.4.23. https://www.kepuchina.cn/tech/info/201804/t20180423_600057.shtml

[6] CSIS: Japan’s Semiconductor Industrial Policy from the 1970s to Today. 2022.9.19. https://www.csis.org/blogs/perspectives-innovation/japans-semiconductor-industrial-policy-1970s-today

[7] Cheng Yuan, Fu Jiajin. A Comparative Analysis of the Development Models of Japan and South Korea’s Microelectronics Industries [D]. Industrial Technology Economics, 2003.

[8] Feng Jinfeng, Guo Qihang. Understanding the Present and Future of the Integrated Circuit Industry in One Book [M], P92—P94.

[9] Hu Huiyin. Aiming at 2nm Chip Production, Can Japan’s Increased Semiconductor Investment Turn the Tide? [N]. 21st Century Business Herald, 2023-04-13 (005)

[10] CCTV: Japanese Media: Panasonic, Sony, and Sharp Reported Combined Losses Exceeding 1.6 Trillion Yen. 2012.5.15. http://news.cntv.cn/20120515/103510.shtml

[11] SIA: 2021 State of the U.S. Semiconductor Industry. 2019.9.27. https://www.semi conductors.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2021-SIA-State-of-the-Industry-Report.pdf

[12] Jetro: The Dependence of South Korea’s Semiconductor Industry on Japan in Terms of Trade Volume. 2019.7.4. https://www.jetro.go.jp/biznews/2019/07/76be05629342286c.html

[13] Luo Junwei, Li Shushen. Strengthening the Construction of Semiconductor Basic Capabilities to Illuminate the “Lighthouse” of Semiconductor Self-Reliance and Strengthening Development [J]. Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2023, 38(2): 187-192.

[14] Nikkei Chinese Network: Japan Plans to Restrict the Export of 23 Types of Semiconductor Equipment. 2023.3.31. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/tIHvA9iQL4jgW0KIeSsqdw

[15] Nikkei Chinese Network: Japan Expands the Scope of Subsidies for Semiconductor Localization Support. 2023.2.7. https://cn.nikkei.com/politicsaeconomy/economic-policy/51329-2023-02-07-09-00-33.html

[16] Zhang Yiyi, Xu Zihao. Semiconductor Materials: Why Does Japan Dominate? [N]. China Electronics News, 2022-06-14 (008)

[17] CSET: The Semiconductor Supply Chain: Assessing National Competitiveness. 2021.1. https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/The-Semiconductor-Supply-Chain-Issue-Brief.pdf

[18] Liu Chunyan. Japan’s Semiconductor Industry: Glory No More, Advantages Still Exist [N]. Economic Reference Daily, 2021-09-06 (002)

[19] Ping An Securities: Semiconductor Materials Series Report (II): Semiconductor Silicon Wafer Edition. 2022.8.17. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202208171577300930_1.pdf?1660754771000.pdf

[20] Guohai Securities: Accelerating the Advancement of Domestic Semiconductor Materials with the Help of Domestic Substitution. 2022.11.26. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202211281580614382_1.pdf?1669645231000.pdf

[21] Dongguan Securities: Electronic Chemicals Series Report One, Broad Space for Domestic Substitution of Electronic Special Gases. 2023.4.27. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202304271585956353_1.pdf?1682616951000.pdf

[22] Tianfeng Securities: Looking Forward to Opportunities for CMP Materials and Equipment Development. 2022.6.20. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202206201573466211_1.pdf?1655740500000.pdf

[23] ZheShang Securities: Photoresists: The Core Bottleneck of the Semiconductor Industry, Domestic Manufacturers Are Preparing to Take Action. 2022.11.13. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202211171580324330_1.pdf?1668682473000.pdf

[24] Kaiyuan Securities: Domestic Wet Electronic Chemicals Leader, Actively Expanding Production, Promising Prospects. 2021.11.12. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202111121528554919_1.pdf?1636718613000.pdf

[25] Guojin Securities: Target Material Leaders Expanding Production Capacity, Riding the Wind of the Semiconductor Industry. 2022.9.20. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202209211578560075_1.pdf?1663771976000.pdf

[26] TechCet: 2022 Semiconductor Materials Market Concludes as Another Solid Year Amid Rising Economic Challenges. https://www.techinsights.com/blog/2022-semiconductor-materials-market-concludes-another-solid-year-amid-rising-economic

[27] Integrated Circuit Materials Research: Overview of Some Japanese Semiconductor Material Manufacturers. 2023.3.17. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/V9NcuBG3XyXY77uRHVeZbg

[28] China Business Intelligence Bureau: Analysis of the Upstream and Downstream Markets and Companies in the Chinese Semiconductor Silicon Wafer Industry in 2022. 2022.10.14. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/hN5sh6yCXJBOKCa4F2kZvg

[29] China Business Intelligence Bureau: A Panorama of the Chinese Photoresist Industry Chain in 2022. 2022.8.5. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/-fTcaaL_CGFaDBjr8_yfCg

[30] Semiconductor Research: Industry Perspective | Overview of Shin-Etsu Chemical: Six Major Businesses Benefit Industrial Consumption, Semiconductor Materials Lead Technological Development. 2021.10.21. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/nJPc5amdggCiFL2dl5rCDg

[31] Semiconductor Research: Industry Perspective | Overview of SUMCO: The Second Largest Silicon Wafer Supplier Globally. 2021.10.13. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/dzDQnuhbVtlAekpzppNhrg

[32] China Chemical New Materials: Historic Opportunities and Challenges Coexist, Domestic Wet Electronic Chemicals’ Localization Faces Heavy Tasks. 2020.8.24. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/c539g7TkHofLAUDT8s8e3w

[33] Huajing Intelligence Network: Domestic Chip Photomasks: The Crazy Dream of a Niche Track. 2022.10.31. https://www.huaon.com/channel/trend/847205.html

[34] Tianfeng Securities: Semiconductor Photoresist-Related Materials Supply and Demand Tight, Domestic Substitution Accelerating. 2022.12.1. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202212021580748726_1.pdf?1669970763000.pdf

[35] Zhiri Community: Hoya Corporation—Those Little-Known Japanese Leading Enterprises (I). 2022.2.27. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/-v-AIDu4P-bb37NvAj57yg

[36] Dongfang Fortune Securities: Semiconductor Materials Series II: Electronic Gases, The Blood of Integrated Circuits. 2022.5.23. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202205201566782555_1.pdf?1653579070000.pdf

[37] Great Wall Guorui Securities: The Industry is in the Early Stage of Domestic Substitution, and Equipment Demand is Strong in 2022. 2022.5.19. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202205191566491722_1.pdf?1652985943000

[38] Tie Jun: Japan’s Restriction Policy Aimed at China, Avoiding Sanctions is Self-Deception. 2023.4.4. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/cVcqa7QXknwIgjemaOfYTw

[39] Tokyo Electron (TEL) 2022 Annual Report: https://www.tel.com/ir/library/report/hq95qj00000007nc-att/fy22q4presentations-e.pdf

[40] Shenzhen Xinyichang Technology Co., Ltd.: Initial Public Offering and Listing on the Science and Technology Innovation Board Prospectus. 2021.4.23. http://file.finance.sina.com.cn/211.154.219.97:9494/MRGG/CNSESH_STOCK/2021/2021-4/2021-04-23/7097900.PDF

[41] Chip Intelligence: The Top 15 Semiconductor Equipment Suppliers Globally: The U.S. and Japan Occupy 11 Places, with Only One Chinese Company on the List! Market Demand is Strong, but Supply is Limited. 2022.6.10. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/q42SgRScwp1m_-PraGqp6w

[42] Chip Intelligence: Japan Plans to Restrict the Export of 23 Types of Semiconductor Equipment! What Impact Will It Have on China’s Semiconductor Industry? 2023.3.1. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Ew3eFkgvp9L3RK8Gz98sSA

[43] Optoelectronic Leading Institute: [Leading Depth]—Deep Dive into the Semiconductor Equipment Industry: Market Driving Factors and Outlook Analysis, Equipment Segmentation and Related Company Deep Review. 2023.4.12. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/B7lc0V8mNWE6JVSaG6zwZA

[44] Zhongyin Securities: Semiconductor Equipment Special Report on Measurement Annual Report. 2021.2.17. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202102181463056835_1.pdf?1613647338000

[45] Guohai Securities: Leading Domestic Chip Dicing Machines for Replacement. 2022.2.16. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202202171547513865_1.pdf?1645089604000

[46] Zhongtai Securities: Huahai Qingke: Domestic CMP Leader, Horizontally Expanding to Build a Platform Company. 2023.4.3. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202304041585094062_1.pdf?1680607889000

[47] Guoyuan Securities: Semiconductor Test Machines, Quality Business Model with Great Potential. 2022.1.8. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202201111539735596_1.pdf?1642178934000

[48] Tech Insights: SEMICON Japan 2022 to Spotlight Innovations Driving Semiconductor Industry Growth. https://www.techinsights.com/blog/semicon-japan-2022-spotlight-innovations-driving-semiconductor-industry-growth

[49] Tech Insights: 2021 Top Semiconductor Equipment Suppliers. https://www.techinsights.com/blog/2021-top-semiconductor-equipment-suppliers

[50] SEMI: The Global Semiconductor Equipment Shipment Value Reached $107.6 Billion in 2022, Setting a New Historical High. 2023.4.13. https://www.semi.org.cn/site/semi/article/c727543d4e384782936f89b98b89ff4b.html

[51] Global Times: Various Sectors in Japan Calculate the Consequences of the Semiconductor “Ban”. 2023.4.3. https://tech.huanqiu.com/article/4CKyMHMgFQh

[52] Economic Reference Daily: Japan’s Semiconductor Industry: Glory No More, Advantages Still Exist. 2021.9.6. http://www.jjckb.cn/2021-09/06/c_1310170031.htm

[53] Jingkai Capital: [Jingkai Capital | Industry Observation] Revealing the Invisible Champions of Global Semiconductor Equipment and Materials: Japan’s Ferrotec | Zhongxin Wafer. 2021.5.31. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/vYBBrOssS_ndgJx-LSu2-g

[54] Semiconductor Industry Observation: Japan’s Semiconductor Invisible Champions. 2021.6.23. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/19vdcWjQMlHq6hfB8Dgimw

[55] Wall Street Journal: Japan Once Led the World in Microchips. Now, It’s Racing to Catch Up. 2022.8.4. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/04/business/japan-semiconductors-chips.html

[56] Jimi Network: Japan Plans to Restrict Photoresist Exports to China? Domestic Investors Panic. 2023.3.10. https://www.laoyaoba.com/n/851895

[57] Jimi Network: Japan’s Semiconductor Equipment Sales Decline for Five Consecutive Months. 2023.4.10. https://www.laoyaoba.com/n/856123

[58] IMD: https://wwwcontent.imd.org/globalassets/wcc/docs/wco/pdfs/countries-landing-page/JP.pdf

[59] Li Haodong. The Development Gains and Losses of Japan’s Semiconductor Industry and Its Implications for China [J]. China Economic and Trade Guide (Theoretical Edition), 2018, (17): 16-19.

[60] China Semiconductor Industry Association: Regarding Japan’s Plan to Expand Export Controls on Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment, the China Semiconductor Industry Association Issues a Serious Statement. 2023.4.28. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/LkSWvzPj3GNJ6M5j8dY-4A