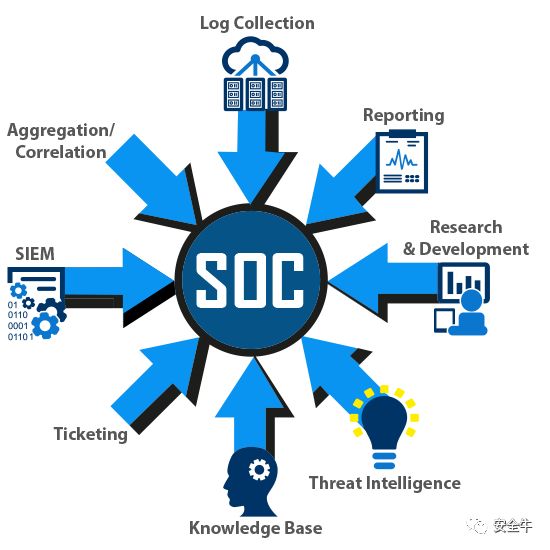

Today’s Security Operations Centers (SOCs) are utilizing emerging technologies to reduce the number of alerts and enhance traditional human collaboration.

Success and failure both stem from SIEM.

For many SOC managers, Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems are both a blessing and a curse: they can integrate and correlate security alerts from firewalls, routers, IDS/IPS, antivirus software, and servers; however, faced with a recent wave of new security tools, threat intelligence feeds, and ever-evolving threats, SOCs are struggling daily in a sea of thousands to millions of security alerts.

Today, many companies are experiencing tool fatigue. Too many tools only deliver partial functionality and are not receiving the attention and feeds they require.

The flood of alerts, uncalibrated tools, combined with the ongoing talent shortage in the industry and the high turnover rate of junior SOC analysts, has forced some companies to rethink and adjust the organization and operation of their SOCs.

In many cases, change is driven by another tool: the next generation of security orchestration and automation tools, which can bridge and automate certain tasks, is replacing manual tasks like clicking through each alert to filter useful information.

SOC operators are also restructuring their teams, breaking down the hierarchical barriers between Level 1, 2, and 3 SOC analysts, fostering more collaborative team operations, allowing analysts to work together to analyze and resolve incidents rather than simply passing the baton to the next level after completing their own tasks.

Once various tools begin to flood information into the SIEM too quickly and excessively, the floodgates open, and SOC analysts can become overwhelmed. Each analyst can only manually handle a limited number of incidents per day, and as incidents come in like a tsunami, SOC analysts can only drown, missing countless incidents and ultimately unable to succeed.

The shortage of security talent is also a significant issue. A recent report from security incident orchestration vendor Demisto stated that about 80% of companies do not have enough analysts to operate their SOCs. Training SOC analysts typically takes 8 months; meanwhile, 1/4 of SOC analysts will change jobs within 2 years. The consequence is that companies spend an average of 4.35 days to resolve a security alert.

The study also found that more than half of companies either do not have an incident response process manual or have one that is not updated. The alert fatigue and daily firefighting faced by security teams can also lead to a side effect that is easily overlooked: stagnation of security processes. Analysts lack the time to capture current process vulnerabilities and update them as needed.

Reclaiming the SOC

Symantec’s SOC operations are relatively large, with six SOCs spread globally. The SOC in Herndon, Virginia, hosts the company’s internal SOC, while another manages security incidents and response services for its clients. A team of over 500 security personnel is responsible for Symantec’s global SOC operations, processing over 150 billion security logs daily.

Symantec’s internal SOC analysts are categorized based on experience and qualifications (imagine a tiered system), but they often work in teams during security incidents. Level 1 analysts are encouraged to handle incidents from start to finish, meaning they are responsible for detection to resolution/response, without necessarily passing it to a senior analyst, although they can seek help from senior analysts.

Symantec’s Joint Security Operations Center (JSOC) recently added Splunk’s Phantom security orchestration and automation platform to integrate security tools and alerts. On the side hosting security services, SOC analysts sit close together, collaborating more during shifts, while Level 1/junior SOC analysts undergo 3 months of intensive training, along with a timed “queue” test simulating an influx of SOC incidents. They must not only solve problems correctly during the queue test but also explain why they chose specific approaches.

Junior SOC analysts will ultimately receive more client calls and participate in on-site client visits.

SOC analysts do not work in isolation; all analysts follow issues from start to finish, with junior analysts learning from senior analysts.

This more advanced and practical role for junior SOC analysts has become a trend: Level 1 SOC analyst roles are expected to evolve closer to Level 2 roles, meaning they can independently analyze flagged alerts rather than helplessly passing them to Level 2 SOC analysts.

In most SOCs, Level 3 analysts are the most technically skilled, capable of deep investigations into threats or malware and conducting forensics. As more Level 1 analyst tasks are automated, Level 3 analysts have more time and energy to perform more proactive testing operations, such as threat hunting. Level 1 and 2 analysts take on more investigative responsibilities.

Insurance companies are deciding to follow the trend of making their SOCs more streamlined and collaborative to better thwart rapidly evolving threats.

Northwest Mutual Life Insurance Company’s new security orchestration and automation tools enable timely handling of inbound incidents, facilitating the transformation of their SOC. Their junior SOC analysts are now more focused on the incidents themselves and the reasons behind them, rather than simply killing alerts to meet company metrics.

This insurance company employs a managed security service provider (MSSP) for 24/7 security operations, truly viewing their SOC as incident response (IR) analyst operations. Therefore, they do not use the conventional “SOC” terminology but instead try to categorize personnel as incident response analysts.

Proprietary Technology

Sometimes, proprietary technology is needed to bridge SOC operations. For example, Aflac has a centralized SIEM and a behavioral analysis platform that processes terabytes of security log data daily within its SOC. This system is bridged by Aflac’s privately created risk algorithm, which can aggregate and filter alerts. By combining automation, analysis, and risk scoring, Aflac has reduced its alert volume by approximately 70%.

The role of junior SOC analysts at Aflac has also changed. They no longer manually click through each raw alert to ignore or escalate it like traditional Level 1 analysts. Aflac’s technology stack has somewhat automated the work of Level 1 analysts.

Junior analysts at Aflac check pre-screened alerts, perform analysis and testing, and if they deem it worth investigating, they send it to Level 2 analysts.

Even so, the SOC still operates in a traditional tiered model, with each level having more advanced responsibilities than before. Level 2 analysts are responsible for the initial investigation of incidents, then passing confirmed incidents to the incident response team. Level 3 analysts provide forensic investigations and typically possess deep endpoint and network analysis skills.

Another tool changing Aflac’s SOC operations is deception defense technology. This is a form of next-generation honeypot that can further minimize false positives and serves as insurance against the unknown.

Deception defense decoys provide SOC analysts with unique insights into attackers and their methods, which can be shared with other team members to take appropriate defensive actions. Deception defense can also promote collaboration between security teams and business units, and because it can be deployed wherever business units desire, it can accelerate the adoption of new technologies.

Some SOC operators wish to streamline personnel as much as possible. One method of streamlining is to fully automate Level 1 analyst tasks, integrating them into orchestration and automation platforms. This allows Level 2 analysts to become rapid responders, while Level 3 analysts focus on more proactive threat hunting and incident response work.

Thus, while personnel may be streamlined, more trained individuals capable of advanced tasks like penetration testing can operate the SOC with smaller teams.

Blending Hierarchies

In the SOC of managed security service provider MKACyber, data and detection are organized by use case and attack type, effectively guiding junior analysts through the SOC process. The goal is to break down the tiered operational model and operate the SOC more collaboratively. Analysts face a series of “gates” that guide them step by step through the security operations process.

For example, when a phishing email triggers an alert, the process flow will instruct them to go through review steps to confirm whether the alert is indeed an incident that requires further processing. Then, the junior analyst uploads all incident details, which are reviewed by senior analysts who approve them for the next level of processing.

By integrating approval processes and incident response actions, analysts at all levels can work collaboratively.

In the next 5-10 years, SOCs may increasingly be cloud-based. Integrating vulnerability management and mitigation into SOCs could further benefit company SOC operations.

Data processing within SOCs will also continue to evolve. In the coming years, the SIEM model may be abandoned, with analysts increasingly engaged in tagging and data science research.

Related Reading

Building SOAR from Scratch

The Evolution of Security Orchestration, Automation, and Response (SOAR) Platforms

Symantec Unveils the World’s Largest SOC to Enhance Threat Capture, Incident Response, and Security Analysis Capabilities