The term robots originates from the 1921 play “Rossum’s Universal Robots” by Czech writer Karel Capek. In this play, robots refer to mechanical beings manufactured in factories. Compared to modern robots, these “beings” should more accurately be described as cyborgs or artificial humans, as they resemble humans and possess their own thoughts. After awakening, these robots discover human selfishness and greed, ultimately rising against oppression, leading to the destruction of humanity.

Though translated as “human,” the word Robot actually comes from the Czech word “Robota,” meaning slave. In broad terms, robots can be understood as automated machines that serve humans (enslaved by humans), generally referring to artificial machines capable of automatically performing tasks.

The term robot first entered the historical stage in 1921, yet prior to this, human exploration of automated machines can be traced back to ancient times.

The earliest recorded automated machinery can be found in the guide car described in the “Notes on Ancient and Modern” by Cui Bao during the Western Jin Dynasty, also known as the south-pointing chariot. Legend has it that the guide car was invented by Emperor Xuanyuan or Duke Zhou. The “Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital” notes: “The south-pointing chariot drives four, in the middle of the road.” In 235 AD, during the Three Kingdoms period, Ma Jun of Wei created the guide car, using a differential gear mechanism to drive a small figure that indicated direction above the carriage. This device did not use magnetic poles and was a fully mechanical automated machine.

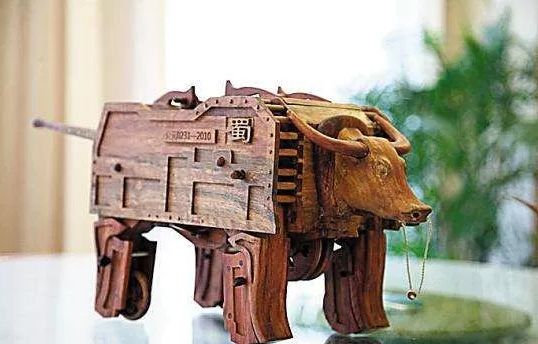

During the Eastern Han period, Zhang Heng, Zhuge Liang and Ma Jun of the Three Kingdoms period, Zu Chongzhi of the Southern and Northern Dynasties, and Su Song of the Northern Song Dynasty each constructed remarkable automated devices in China’s history. These devices reflect the outstanding wisdom of ancient sages and embody the people’s long-standing thoughts and efforts to use automated machinery to liberate production.

Other civilizations around the world have records of robots tracing back to Homer’s epic “The Iliad,” where the fire god Hephaestus created a set of wooden automata as his assistants. The earliest verifiable automated devices can be traced back to the 16th century BC in ancient Babylon and ancient Egypt with the water clock. The water clock is a mechanical timing tool, also known as a clepsydra, which allows water to flow out of a container to measure time based on the remaining water volume. The Greeks and Romans added transmission and escapement mechanisms to the water clock, enhancing its accuracy to some extent.

In 400 BC, Plato’s friend, the father of mathematical mechanics, Archytas, designed the first flying wooden machine resembling a pigeon. By the 2nd century BC, the ancient Greeks invented the earliest automaton, powered by water, air, and steam pressure, which could move as a statue. Later, automatons developed in the 18th to 19th centuries into machines operated by spring mechanisms.

From the 8th to the 17th century, Europe experienced the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Al-Jazari invented segmented gears and created numerous water-driven automated machines, including an automated peacock and a waitress that could refill cups. Al-Jazari’s manuscripts also influenced Leonardo da Vinci, who applied his anatomical studies to humanoid machines. His mechanical knight, driven by a series of pulleys and gears, could move its arms and head and could sit and stand. In 14th century Europe, mechanical clocks emerged, and the clockmaking industry began to thrive, attracting nobles to collect various ornamental clocks. In the 15th century, Hanslein of Nuremberg invented the world’s first portable timekeeper, simultaneously inventing the clock’s spring structure. The development of the clock industry later drove the advancement of automated machines.

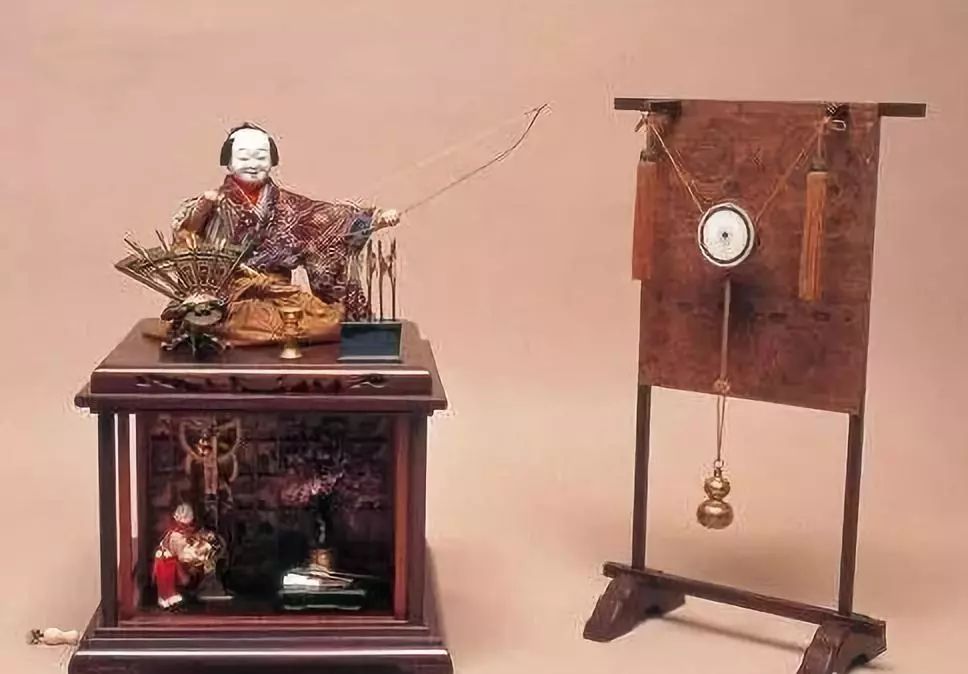

Entering the 17th century, skilled clockmakers crafted exquisite automated machines. In 1662, Takeda Omi applied clock technology to the making of automated dolls, using whale bone and wooden gears to create the “Takeda-style automaton.” Surviving artifacts include the “Tea Serving Doll,” which is a wheeled puppet that holds a tea tray with both hands and moves forward when a teacup is placed on the tray, stopping automatically when a guest takes the teacup.

From the 18th century to the mid-19th century, Europe experienced the first Industrial Revolution, ushering in an era of machines replacing manual labor, also known as the machine age. The Industrial Revolution originated in 18th century Britain, with the improvement of the steam engine by Watt leading to a series of technologies that transformed manual labor into machine production, subsequently spreading to the European continent and then to the Americas and Asia. In 1738, French clockmaker Bouchon created a mechanical duck powered by gears, capable of flapping its wings, quacking, and pecking at grain.

In 1770, Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen built the “Turkish Chess Automaton” to entertain Grand Duchess Maria Theresa, which could defeat human chess players and execute “knight patrols.” In 1854, this robot began touring performances until people discovered that a chess master was concealed within the intricate machine.

Between 1768 and 1774, Pierre and Henri Jacques de Vaucanson created three moving doll robots to promote his clock business. This set of automated dolls includes “The Writer,” “The Musician,” and “The Draughtsman,” consisting of 6000, 2500, and 2000 components, respectively. Among them, “The Writer” is a robot resembling a three-year-old boy, powered by a spring, which, once wound, dips a quill in ink and writes predetermined phrases on paper. To enable the robot to create different phrases, Vaucanson produced 40 read-only discs, which can be seen as a prototype of a programmable robot.

In 1801, French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard designed the first programmable loom, greatly enhancing weaving efficiency. To control the weaving patterns on the loom, Jacquard developed a system of punched cards. This system later inspired IBM’s creators to use punched cards for data recording and computer programming.

In 1822, British mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage proposed the design concepts for the Difference Engine and the Analytical Engine and created some prototypes. His idea was to use machines to automate the processes from calculation to printing, thereby avoiding human error. The machines he proposed utilized the properties of polynomial Nth differences, driven by gears to perform decimal addition and subtraction. Due to the complexity of the craft, manufacturing a large number of precision instruments was difficult, and only a few complete products could be made at that time.

In 1945, Austrian inventor Joseph Faber exhibited his invention, the “Singing Bird” robot, at camera shows in Philadelphia and London. This robot was a talking machine composed of several different mechanical devices and instruments, including a piano, a harmonica, and a mechanical throat as a sound generator. The machine connected a human-like face to a keyboard, allowing the lips, chin, and tongue to be controlled, with adjustments made to the screws on the nose to modify pitch and accent.

By the end of the 19th century, major Western countries had essentially completed the Industrial Revolution, leading to a surge in scientific and technological advancements. American inventor Nikola Tesla invented radio and designed and demonstrated a radio-controlled boat model in 1898. This robotic remote control technology did not become widespread until decades later.

In 1927, American engineer Wensley created the first robot telegraph box. This robot was equipped with a radio transmitter and could answer some questions.

In 1929, Japanese biologist Nishimura Makoto created the “Gaku Tenze” robot. This robot could write and change expressions, standing approximately 3 meters tall, holding a pen in its right hand and a lamp in its left. Its face was made of rubber, and its eyes, cheeks, mouth corners, neck, and wrists could all move. Its large movements were powered by compressed air and rubber tubes.

Source: Mr. De