Abstract: In the first half of the 18th century, French Father Du Halde published the monumental work “General Description of the Chinese Empire”, which described the civil and military achievements of Song Dynasty China. In his writing, the rulers of the Song Dynasty valued culture, respected knowledge, and honored the intellectual class, leading to brilliant cultural achievements domestically. Du Halde recorded various measures taken by the Song monarchs to “respect Confucius”; on one hand, he presented this as evidence of the Song’s emphasis on civil governance, while on the other hand, he argued that the worship of Confucius was entirely a secular activity, defending the Jesuits caught in the “Chinese Rites Controversy”. Du Halde pointed out the characteristic of the Song monarchs as “emphasizing culture over military”, and when it came to wars involving the Song Dynasty and neighboring ethnic regimes, he defended the Song from multiple angles, unwilling to overly emphasize the “decline” of China in foreign wars, lest it damage the glorious image of the empire. He strived to depict a scene where the Song Dynasty was under the rule of scholars, and the wars that occurred were all unavoidable, with virtuous scholars advocating a peaceful foreign policy and opposing military expansion. Du Halde established an image of the Song Dynasty in the European intellectual community as a culture-loving and non-militaristic society, enriching the thoughts of the European intellectual community and making the Song Dynasty China a mirror reflecting European society.

Keywords: Song Dynasty Emphasizing Culture Over Military Du Halde “General Description of the Chinese Empire”

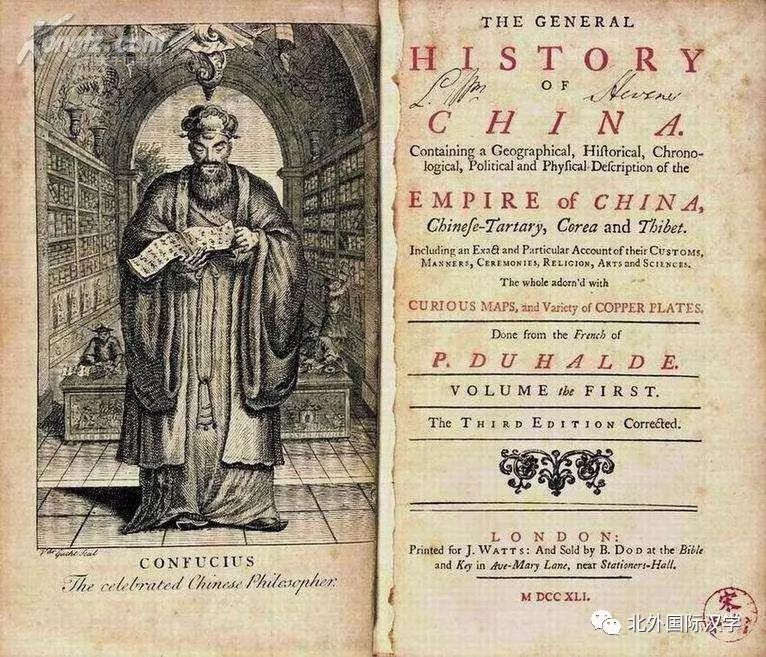

When mentioning the Song Dynasty, people often lament the huge contrast it presents in terms of civil governance and military achievements, with a flourishing cultural governance and a lack of military competition, a label that has long been attached to the history of the Song Dynasty. On one hand, people praise “the culture of the Huaxia nation, which has evolved over thousands of years, reaching its peak during the Zhao and Song eras”; on the other hand, they are pained by the Song army’s repeated defeats in foreign wars, viewing the Song government as servile and even as a period of national humiliation and loss of sovereignty. Compared to domestic scholars’ anger at the Song’s failures, Western scholars pay more attention to the heights of civilization reached by Song Dynasty China and its cultural achievements. French sinologist Jacques Gernet once said: “Looking at China from the 11th to the 13th century, one can feel the astonishing development of economy and knowledge. … The gap between East Asia and the Christian West is exceptionally clear; just by comparing the Huaxia world with the Christian world in every field (trade volume, technological level, political organization, scientific knowledge, literature, and art), one can be certain that Europe is greatly ‘behind’. Undoubtedly, the two great civilizations of the 11th to 13th centuries are Chinese civilization and Islamic civilization.” Western sinologists have given high praise to the civilization of the Song Dynasty, but this does not mean they ignore the imbalance in the development of civil and military aspects during the Song Dynasty. Ray Huang pointed out several seemingly paradoxical phenomena in Song history, including its brilliant cultural achievements and its military ineffectiveness. The question of when and where the Western academic community’s impression of Song history began is one that the history of scholarship needs to answer. In the first half of the 18th century, French Father Du Halde published the monumental work “General Description of the Chinese Empire” (Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique et physique de l’Empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie Chinoise, 1735, abbreviated as Description de la Chine), which described and evaluated the civil and military performances of Song Dynasty China, influencing Western scholars’ understanding of Song history for nearly two centuries thereafter. This article attempts to discuss the image of “emphasizing culture over military” presented by Du Halde in his work.

French Sinologist Jacques Gernet

1. The Image of the Song Monarchs “Emphasizing Culture” in a Religious Context

The Song Dynasty inherited the problems of the Five Dynasties. To reverse the long-standing imbalance between civil and military affairs and remedy the resulting social turmoil, Song Taizu laid the foundation for “civil governance” as the founding principle, and the subsequent monarchs followed this model, ultimately establishing a social trend of “valuing culture”. At the beginning of the overview of Song history in the “General Description”, it points out the tendency of Song monarchs to “emphasize culture over military”: “After entering the Song Dynasty, the country recovered from previous chaos, wars, and other disasters, entering a long period of stability. If the Song monarchs could value military affairs as much as they value culture, the happiness brought by peace would last even longer.” The prosperity of culture cannot be separated from the tolerance and support of the rulers. The Song monarchs’ encouragement of literature and culture ultimately led to the comprehensive flourishing of Song culture: “Before the Song Dynasty, due to various disasters caused by religions and wars, the country lost its love for scholarship, ignorance and degeneration prevailed, and no scholar could awaken people’s will in the general malaise. Only the Song rulers’ love for ancient classics and respect for scholars gradually revived literature.”

Du Halde meticulously enumerated the performances and measures of the Song emperors in “emphasizing culture”. For example, Song Taizong generously supported scholars; he himself was well-educated and set aside fixed time every day for reading. He had a library with a collection of 80,000 volumes. Song Zhenzong reprinted ancient classics and distributed them nationwide; Song Huizong loved literature and was quite accomplished; Song Gaozong was of a peaceful character and loved knowledge. The crisis of the times required a militaristic monarch, but Lizong was completely immersed in science. In Du Halde’s writings, the Song monarchs were a group with high cultural cultivation, a love for knowledge, respect for scholars, and a preference for culture over military. They may have various issues, such as Song Zhenzong’s devotion to Taoism and Song Huizong’s indulgence in pleasure, but overall they were filled with reason and far from ignorance.

When discussing the Song monarchs’ performance in “emphasizing culture”, Du Halde frequently mentioned their reverence for Confucius. On the surface, this was to highlight their emphasis on civil governance, but upon further reflection, it is closely related to the background of the “Chinese Rites Controversy” in Europe at that time. The “Chinese Rites Controversy” was a debate among different religious orders sparked by the Jesuit missionary strategies and understandings of Chinese culture, with the worship of Confucius being one of its core issues. The focal point of the controversy was whether the worship of Confucius had religious nature and whether Chinese Christians were allowed to participate in the rituals. Matteo Ricci believed that the worship of Confucius was a political and secular humanistic activity rather than a religious heretical ritual:

The Confucian temple is the only temple for the upper-class literati of Confucianism. Laws require that a temple for the king of Chinese philosophers be built in every city, regarded as the cultural center of that city. … Every new moon and full moon, ministers and scholars gather at the Confucian temple to pay respects to their ancient teacher. The rituals in this situation include burning incense, lighting candles, and bowing. Every year, on Confucius’s birthday and on other customary dates, exquisite dishes are offered to Confucius to express gratitude for the teachings contained in his writings. They do this because it is through these teachings that they obtained their degrees, and the country received excellent public administrative authority from those who were granted ministerial positions. They do not pray to Confucius, nor do they request him to bestow blessings or hope for his assistance. The way they respect him is akin to how they respect their ancestors.

Ricci explained that the worship of Confucius was a form of Confucian education and the imperial examination system, rather than a religious prayer akin to worshiping gods. Most Jesuits after him also inherited his view: “The worship of Confucius and ancestor worship is purely non-religious and does not contradict Catholic doctrine.” The Jesuit viewpoint drew criticism from other factions such as the Dominicans and Franciscans, who argued that Confucius was not only a revered teacher worshiped by scholars but also an idol revered as a deity, and the worship of Confucius was a religious heretical act that should be strictly prohibited.

Faced with the united attacks of other factions, the Jesuits had to send someone to the Roman Curia to explain. Louis Le Comte defended: “As for people’s reverence for Confucius, it is not a form of religious worship, and the Confucian temple named after him is not a real temple; it is merely a gathering place for scholars.” Jesuits also published a large number of works to seek understanding and support from others, and the “General Description” undertook this mission. Like Ricci, Du Halde attempted to explain the worship of Confucius from the perspective of governance and education. In recording Zhu Xi’s visit to the Confucian temple during the reign of Song Ningzong, he mentioned a Chinese “tradition”: if a person has outstanding morals or remarkable governance abilities, the emperor would include him among the disciples of Confucius, allowing him to receive the respect of officials and scholars at specific times each year alongside Confucius. This “tradition” indirectly proves that the worship of Confucius is out of respect for moral and governance abilities, unrelated to superstition.

Song Huizong

Du Halde mentioned that the “Tartar” (tartar) monarch Jin Xizong, in order to win the love of his subjects and show respect for knowledge and scholars, visited the Confucian temple and emulated the Chinese monarchs in bestowing royal honors. The ministers were quite dissatisfied that Confucius, who had a humble background, received such honors. Jin Xizong replied: “If his background is not enough to receive these honors, his outstanding teachings are sufficient.” Regarding Jin Xizong’s reverence for Confucius, the “Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government” records:

The Jin ruler personally worshiped Confucius, bowed to him from the north, and said to his attendants: “Although Confucius has no official position, his teachings deserve respect and should be admired by all generations. Generally, to do good is something one should strive for.” He began to read the “Book of Documents”, the “Analects”, and histories of the Five Dynasties and Liao. One day, when Wuzhu sent envoys to report a victory, many ministers presented poems to congratulate him. The Jin ruler read them and said: “In a peaceful world, we should value culture, and throughout history, good governance has always been derived from this.”

The narrative in the “General Description” clearly has a certain degree of misalignment with the original historical texts. In the original text, Jin Xizong’s various measures ultimately culminate in the statement: “In a peaceful world, we should value culture, and throughout history, good governance has always been derived from this.” From his perspective, during peaceful times, attention should be paid to cultivating a cultural atmosphere to achieve a perfect social order, and the worship of Confucius and other measures are aimed at this purpose. In contrast, the “General Description” seeks to explain that the reason Confucius is widely respected is entirely due to his teachings, thereby eliminating the religious factors in the worship rituals.

Du Halde’s account of the Song monarchs’ reverence for Confucius contains a clear religious purpose. He is not merely highlighting the Song people’s “emphasis on culture”; more importantly, he is defending the Jesuits’ missionary strategy. For this purpose, he deliberately stripped some historical events from their original historical context, resulting in intentional distortion and rewriting, during which the historical significance carried by the events was diminished. The account of Jin Xizong’s reverence for Confucius reveals this tendency, while the account of Song Taizu’s reverence for Confucius clearly proves this point. Du Halde recorded that Song Taizu, to encourage learning, visited Confucius’s hometown, wrote praises, and conferred rewards on Confucius’s descendants. This record likely pertains to the event of “Song monarch viewing education” in the first year of the Jianlong era (960), as recorded in the “Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government”:

The edict ordered the repair of the temple, the statues and paintings of the sages and worthies were made, and the emperor himself wrote praises for the seats of Confucius and Yan, ordering the civil officials to compose additional praises, frequently visiting the temple. He once told his attendants: “I want military officials to read books so that they know the way of governance.” As a result, scholars began to be valued.

The original text after Song Taizu’s “viewing education” still contains the phrase “I want military officials to read books so that they know the way of governance”. This statement has a clear political orientation and outstanding political significance within the political context of early Song, as it was an important measure to reverse the rampant military authority, balance the disordered civil and military relations, and rebuild the hierarchical relationship between monarch and ministers during the specific historical period of the transition from the Five Dynasties to the Song. Song Taizu’s “viewing education” has been highly praised by traditional Chinese historians. In the “Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government”, Ming scholar Zhou Li commented: “The viewing of education by the Song monarch is seen at the beginning of acquiring the country; the spirit and lifeblood of the Song’s three hundred years of foundation lies in this. From then on, Confucianism and Daoism gradually revived, leading to a great flourishing of literature between the Guanzhong, Fujian, Lian, and Luo regions.” In Zhou Li’s view, Song Taizu’s actions laid the foundation for the three hundred years of the Song Dynasty’s achievements and established the “cultured and refined” characteristics of the Song Dynasty, thus having a far-reaching impact. Du Halde’s narrative aims to highlight the connection between the worship of Confucius and the encouragement of learning, providing an explanation for the respect for Confucius, but he fails to grasp the deep historical trends of restoring order through civil governance during the transitional period from the Five Dynasties to the Song, and thus does not truly touch upon the pulse of Song history.

In Du Halde’s explanation, the worship of Confucius does not contain any religious factors; it is related to the humanistic spirit of respecting and pursuing knowledge, and it is also connected with morality and governance. This aligns with the pursuit of humanistic spirit, morality, and governance in the European intellectual community at that time, providing strong support for the Jesuits’ tolerant strategy. Not only did the Song emperors show great respect for Confucius, but even the “barbarians” who invaded China were no exception. Jin Xizong revered Confucius to gain the love of his subjects, and Yuan Shizu Kublai Khan also won the goodwill of his subjects by respecting scholars and venerating Confucius. These examples remind the Roman Curia and those prejudiced against the Jesuits that the practices of Jesuits have clear historical basis. To make Christianity accepted by the Chinese, respecting Confucius has proven to be an effective approach, thus giving rationality to the Jesuits’ adaptive policy.

2. The Caution of the Song People Towards War

Du Halde wanted to convey an image of a civilized, rational, and enlightened Chinese Empire to Western readers, and the brutality of war was something he wished to obscure. However, at the same time, for most of the time during the Song and Jin Dynasties, the Central Plains dynasty faced threats from neighboring ethnic regimes, and the pressure of war affected every aspect of domestic politics. This objectively made it impossible to ignore war when discussing this period of history. The “General Description” mentions several large-scale wars that occurred during the Song Dynasty, but in general, it only reports the results and impacts of the wars, avoiding involvement in the specific processes of the wars. For example, regarding the unification wars at the beginning of the Song, it is summarized in one sentence: “Taizu, with his good character, lowered himself to re-submit to the various nations, restoring peace.” Historically, the Song Dynasty suffered repeated defeats in foreign wars, and thus was labeled as “weak”, but Du Halde did not highlight the Song’s failures; instead, he used some neutral phrases to defend the Song, which represents “China” from multiple angles. Regarding the two large-scale northern expeditions during the reign of Song Taizong, Du Halde summarized them as “both sides had victories and defeats”; during the Song-Jin War, Song Gaozong’s retreat under the pursuit of the Jin army was beautified by Du Halde as Song Gaozong “achieved several victories against the Tartars and suppressed rebellions”.

War itself was not the main subject of Du Halde’s investigation; his intention was not to reveal the causes, processes, impacts, etc., of wars but to convey the ideal image of “China” through war. When discussing the wars between the Song Taizong and the Liao Dynasty during Song Taizong’s reign, Du Halde wrote:

Taizong urgently hoped to recover the cities previously ceded to the Khitan, but the army commander Zhang Qixian always advised him to give up this idea. He said: “First, we should ensure the peace of the empire; after achieving this goal, we will easily eliminate these barbarians.” However, Taizong did not heed this advice, and several battles occurred, with victories and defeats on both sides. Zhang Qixian employed extraordinary strategies while lifting the siege of a city, sending 300 soldiers, each carrying torches, marching in formation toward the enemy camp. The enemy was intimidated by so many torches, thinking it was the entire army attacking them, and fled in panic.

In the fourth year of Taiping Xingguo (979), Song Taizong led the army to destroy the Northern Han and then moved to attack Liao, intending to recover the Youyun region in one fell swoop. As a result, the Song army suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Gaoliang River, with Taizong being hit by two arrows and barely escaping. The following year, a minister suggested another attack on Youji, and Zhang Qixian wrote to advise against it, arguing that first, we should select border generals carefully, which would allow the border regions to be settled and the people of Hebei to rest; secondly, he proposed, “First secure the interior, then address the exterior; nurture the people to support the outside.”

By the third year of Yongxi (986), after several years of recuperation, Taizong launched another northern expedition, but it ended in another crushing defeat. Due to the death of the general Yang Ye, Zhang Qixian was appointed to take over the command of the army. The record of Zhang Qixian’s victory over the enemy in the “General Description” occurred at that time. The “Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government” records:

The emperor, upon hearing of Yang Ye’s death, inquired among his close ministers about someone who could take over the command of Daizhou. Zhang Qixian volunteered and was appointed. Zhang Qixian defeated the Khitan at Tudu Fortress; the Khitan were thinly stationed at Daizhou city, and Zhang Qixian sent envoys to request Pan Mei to join forces for battle, but was captured by the Khitan. Shortly after, Mei’s envoy arrived, stating that his troops had reached Baijing, and received a secret edict not to engage in battle, and returned to the city. Zhang Qixian said: “The enemy knows Mei is coming but does not know he is retreating”; he then launched a night attack with 200 men, each carrying a banner and a bundle of fodder, setting up banners and lighting the fodder thirty miles southwest of the city. The Khitan troops, seeing the lights and banners, believed the reinforcements had arrived and fled in panic. Zhang Qixian then ambushed 2,000 infantry at Tudu Fortress and dealt a heavy blow to them.

As mentioned above, the “General Description”‘s account of the Song-Liao wars during Taizong’s reign is actually a compilation adapted from multiple sources. The events regarding Zhang Qixian’s letter occurred in the fifth year of Taiping Xingguo, when he served as a left historian, not as the “army commander” as claimed in the “General Description”. His victory over the Liao occurred much later, in the third year of Yongxi. Apart from these narrative errors, what is more thought-provoking is the way the “General Description” narrates this war; in the two northern expeditions of Taizong, Zhang Qixian does not occupy a prominent position, but the “General Description” centers on this “marginal figure”, which is quite intriguing. The reason for this is that the case of Zhang Qixian sufficiently reflects the points Du Halde wants to express: first, the Chinese intellectual class opposes initiating wars; second, the Chinese display extraordinary wisdom and virtue in wars.

Du Halde seeks to illustrate that under the governance of intellectuals and scholars, wars that occur are mostly unavoidable, and scholars oppose war, advocating a peaceful foreign policy. Du Halde recorded that Song Shenzong was eager to expand the borders, but his mother’s ministers advised him to maintain peace at all costs. As proof, the “General Description” included Su Shi’s “Memorial on Restraining Military Actions”, which was written by Su Shi while passing through Nandu in the tenth year of Xining (1077). In the text, Su Shi wrote: “The affairs of the rebellious people are not one, and those who love war must perish; this is the inevitable principle.” He pointed out that blindly engaging in war not only leads to national chaos after defeat but also brings destruction to the country even in victory. He cited Qin Shi Huang, Han Wu Di, Sui Wen Di, and Tang Taizong as examples to prove that “victory leads to delays and great disasters, while defeat leads to quick but small disasters”, advising Shenzong to “look far back at the rise and fall of the past, deeply observe the principles of heaven’s will, and abandon military actions, maintaining peace and quiet.” This essay is regarded as a representative work of ancient Chinese admonitions against engaging in war, with Southern Song scholar Huang Zhen calling it “truly a warning for future rulers and ministers who favor war”. Ming Dynasty scholar Mao Kun praised it as the top article on ancient military strategy, “to be shared with heaven and earth.”

Similar to Su Shi’s article, the “General Description” also includes Zhang Shi’s “Memorial to Emperors of the Southern Song”, which similarly advises the emperor to treat war with caution. During Emperor Xiaozong’s reign, Yu Yunwen, wishing to restore the old borders of Northern Song, repeatedly sent envoys to Zhang Shi. Zhang Shi thus wrote this memorial, stating: “If one wishes to recover the land of the Central Plains, one must first win the hearts of the people. To win the hearts of the people, one must not exhaust their resources or harm their wealth. Today’s affairs should fundamentally be based on clarifying the great principles and rectifying the hearts of the people. However, the order of implementation must be detailed, and the urgency must be considered. The matters of name and reality must be examined carefully. This is also something the wise ruler should deeply consider.”

These two memorials together convey to Western readers that the scholars and officials of China hold a negative attitude towards military expansion.

Du Halde attempts to highlight the wisdom and virtue of the Chinese people through the description of wars. During the Song-Jin Wars at the turn of the Song Dynasty, the emperors Huizong and Qin were captured and taken north, and the succeeding Song Gaozong fled south under the pursuit of the Jin army, even having to float on a boat at sea for a time. However, the “General Description” does not show any signs of the Song Dynasty’s embarrassment in this war, instead highlighting three images of the Song people. First, loyal subjects. Li Ruoshui, facing the Jin’s persuasion to surrender, insisted, “There cannot be two suns in the sky; how can Ruoshui have two masters?” and committed suicide by biting his tongue; Yang Bangyi, after being captured, wrote a blood letter stating, “I would rather be a ghost of the Zhao family than a minister of another country.” Second, brave generals. Yue Fei led his army over long distances to rescue Nanjing, inflicting heavy casualties on the Jin army, preventing them from crossing the Yangtze River thereafter. Finally, filial sons. Although Song Gaozong signed a humiliating treaty with the Jin Dynasty, using the terms “subject” and “tribute”, it was to retrieve the remains of his deceased relatives. When the remains of these relatives arrived in Hangzhou, people welcomed them with great joy, and the court announced a general amnesty. Gaozong’s actions received high praise from historians and were seen as a rare example of filial piety.

As mentioned above, war is not the main object of Du Halde’s investigation. In his writings, one rarely sees the Song Dynasty’s defeats and embarrassments in foreign wars; his purpose is to convey the ideal image of Song Dynasty China: under the governance of “philosophers” or scholars, the wars that occur are mostly unavoidable. The scholars love peace, oppose war, and possess high wisdom and virtue. The image of Song Dynasty China established by Du Halde is actually a reflection of the domestic situation in Europe, especially France.

In the 16th to 17th centuries, Europe was constantly embroiled in bloody wars, and the war-ravaged European society fell into a huge crisis by the end of the 17th century. Among European countries, France was one of the nations most severely damaged by wars. Due to continuous involvement in wars and repeated defeats, France’s national strength was severely depleted. Du Halde pointed out the Chinese intellectual class’s understanding and attitude towards wars as a satire of the ruling class in France and even all of Europe. The historical facts he provided enriched the thoughts of the European intellectual community and caused a great response. Oliver Goldsmith, after reading the “General Description”, compared the peace-loving Chinese scholars with Europe’s endless wars, pointing out that from any perspective, there is always a thread running through the entire history of Europe, which is evil, foolishness, and disaster, namely, politics without planning and war without results.

“General Description of the Chinese Empire”

Conclusion

For a long time, Jesuits have formed a consistent understanding of China. In their view, China is a nation with little or no interest in expanding its territory, governed by intellectuals and scholars, where people hold great respect for scholar-officials, while the status of military personnel is relatively low. In China, war policies are planned by intellectuals and scholars, and military issues are decided by them; their suggestions and opinions are valued by the emperor more than those of military leaders. Therefore, all educated individuals disapprove of war; they would rather be the lowest-ranking scholars than the highest-ranking military officials. China neglects the construction of armed forces, with the army lacking valiant spirit, military training being treated as a joke, and the imperial examination only selecting officials based on essays, resulting in a prevailing attitude of emphasizing culture over military.

Du Halde’s “General Description” outlines an image of the Song Dynasty as culturally prosperous and militarily unambitious, which is almost a reflection of the image of China constructed by missionaries before him. This is a highly civilized nation, not only materially affluent but also culturally developed, and devoid of the continuous wars seen throughout European history. The rulers of the Song Dynasty valued culture, respected knowledge, and honored the intellectual class, forming a group filled with humanistic spirit and rational temperament. Under their support, Song culture achieved brilliant accomplishments. Du Halde recorded the various measures taken by the Song monarchs to “respect Confucius”; on one hand, this can be seen as evidence of the Song monarchs’ emphasis on education and civil governance, while on the other hand, it is filled with strong religious connotations. His aim was to demonstrate that the worship of Confucius is entirely a secular activity, fundamentally different from idol worship, thereby defending the Jesuits caught in the “Chinese Rites Controversy”. Because of this purpose, Du Halde purposefully edited and rewrote historical materials, distorting their original meanings and obliterating the historical significance of the events, resulting in his narrative failing to reveal the characteristics of Song history and not genuinely touching upon the deep currents of Song history.

Du Halde’s narrative of Song history serves the overall purpose of establishing an image of a civilized and enlightened empire. Therefore, when it comes to the wars between the Song Dynasty and neighboring ethnic regimes, he defends the Song Dynasty from multiple angles. Song Taizong’s two northern expeditions and the Song-Jin wars at the turn of the Song Dynasty both resulted in painful defeats, yet such traces are hard to find in the “General Description”. Du Halde clearly does not wish to overly emphasize the “decline” of “China” in foreign wars, lest it provoke contempt from Western readers. War itself is not the main subject of Du Halde’s investigation; his descriptions of wars do not aim to explore the causes, processes, or impacts of wars but to convey the wisdom and virtue of the Song people. This image of Song Dynasty China does not entirely derive from Song historical materials; it is also a reflection of the continuous wars in Europe, especially France, and serves as a caution to the ruling classes in Europe. Du Halde’s description of the Song intellectual class’s attitude and views towards war established an image of the Song Dynasty as “emphasizing culture over military” in the European intellectual community, while also enriching the thoughts of the European intellectual community, making Song Dynasty China a mirror reflecting European society.

This article was originally published in International Sinology, Issue 2, 2018.