Source / Knowledge Automation (ID: zhishipai)

Author / Lin Xueping

Cover / Tuchong Creative

China’s manufacturing is large but not strong, and the instrumentation industry is not even considered large, it can only be said to be numerous but not substantial. The domestic leaders in instrumentation are merely a fraction compared to foreign manufacturers. Even with such a scale, it still grows on the foundation of foreign sensors. Moreover, domestic sensors are even smaller in scale and lack leadership.

1/ The Octopus of the Manufacturing Food Chain

Without sensors to perceive the source of all things, intelligence is unimaginable; in any factory or laboratory, without instruments for measurement, the operational trajectory of machinery and equipment will lose all clues. Data will be frozen, and knowledge will be hidden. All things in the universe operate under physical laws, while the human world operates on sensors and instruments.

As a manufacturing powerhouse, although many low-end manufacturing jobs have permanently left the U.S., many major manufacturers have factories in China, such as Honeywell, which had 21 production plants in mainland China by 2020. However, this is just a facade. The U.S. still holds the dominant position in the high-end manufacturing sector of the manufacturing food chain.

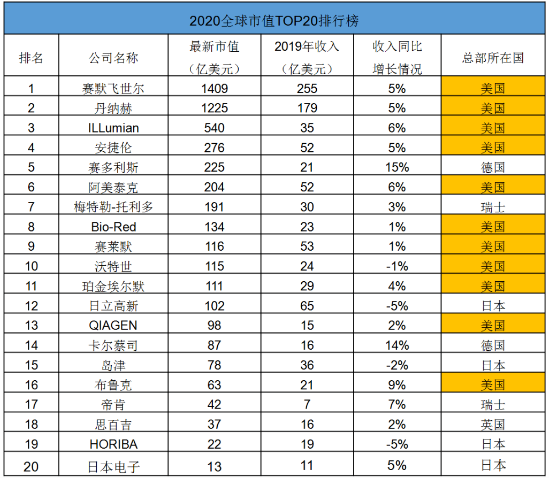

The top U.S. instrument manufacturers not only control almost all the fish in the instrument pool but also possess more advanced fishing techniques: the ability to develop and manufacture sensors. Through alliances and acquisitions, the U.S. has formed massive industrial groups in instrumentation and sensors. Among the top 20 scientific instrument companies in the world, 11 are from the U.S.; and among the top 10, the U.S. holds 8 positions.

Table 1/2020 Global Instrument Company Market Value and Revenue (Source: Instrument Information Network)

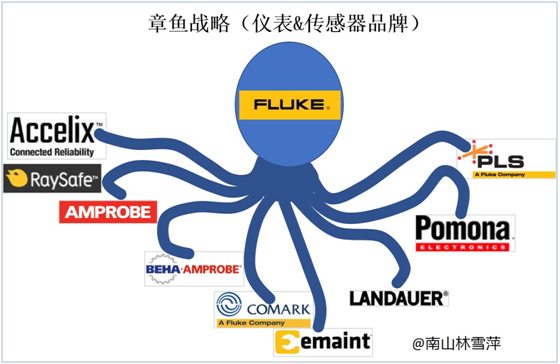

If we analyze U.S. instrument and sensor manufacturers closely, we will find that these groups adopt a clear brand matrix layout strategy. For example, the instrument manufacturer Ametek had a revenue of $5.2 billion in 2019 and has more than ten subordinate brands. The instrument group Fluke (which originally separated from Danaher Group) is expected to have a revenue of $1.4 billion in 2020 and also has ten brands; while the world’s largest instrument company, Thermo Fisher Scientific, controls hundreds of brands. This group-based brand matrix strategy connects different ponds, with tentacles that almost firmly grasp the high-end manufacturing field of instruments and sensors.

Figure 1/The Octopus Strategy of U.S. Fluke

The way U.S. manufacturing controls the food chain presents a unique form: the group development of independent brands resembles an octopus. Through the advantages of group and diversified tentacles, it ensures that even sub-brands with only tens of millions in revenue can survive in niche markets. U.S. instrument manufacturers and sensor manufacturers often adopt a relationship akin to the palm and back of the hand, where sensors can supply other brands while also ensuring their own core competitiveness in instruments.

The octopus employs a two-layer supply chain control method. There is the first control chain, such as instruments: it can control the entry of measurements, and its output value is easy to scale; and there is the second control chain, where sensors act as a defensive chain. Sensors, which are large in quantity but small in scale, have achieved stable growth under the protection of the U.S. octopus. One center, with eight sides. The octopus strategy supports the relatively small market at the top of the pyramid.

2/ All Octopuses, Just Bigger or Smaller

In the U.S. instrumentation industry, apart from smaller companies like Felixinstruments, which was established later (2011) and specializes in agricultural gas analysis products, most small and medium enterprises have become subsidiaries of larger groups.

One type is the giant octopus that develops broadly. For example, the comprehensive Ametek is a leader in the sensor field (the Meas Group of precision electronic sensors, covering everything from civilian to various industrial equipment). In extreme cases, Thermo Fisher Scientific has over a hundred brands and sales reaching $26 billion.

Another type is the small but strong octopus, which excels in a specific niche. For instance, the Process Insights instrument group owned by an American investment company has many leading brands in specific instrument fields acquired through mergers, such as Lar.

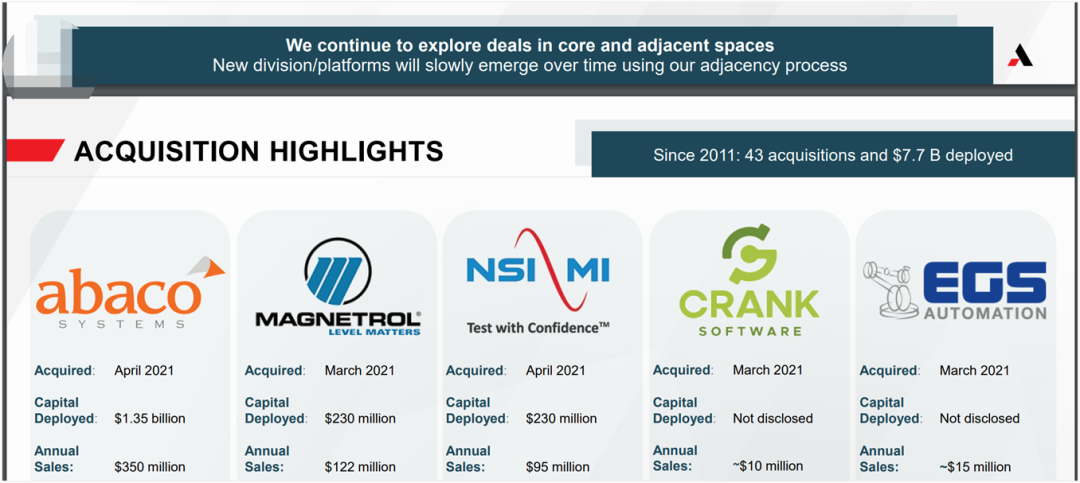

As a $5 billion company, Ametek includes two operational groups: one is the electronic instruments group, and the other is known for electrical interconnects and precision motion control solutions, the mechatronics group. The differences in business between the groups can sometimes exceed external imagination. In the past decade, it has acquired nearly 50 companies, with a total acquisition amount exceeding $7.7 billion. In less than half a year in 2021, acquisitions alone reached $2 billion. The size of the octopus is growing.

Figure 2/Ametek’s Continuous Acquisitions (Source: 2021 Annual Report)

Ametek’s sub-brands resemble a military formation, with experts aplenty. For example, the British company LAND, originally produced industrial infrared non-contact temperature measuring instruments, and its temperature laboratory is almost one of the most complete laboratories in the world. Its fully self-produced products, such as blackbody furnaces, can provide precise calibration for industrial high-temperature thermometers, thermal imaging cameras, and thermocouples, with very few competitors. However, the UK has many high-quality manufacturing brands, but many are becoming prey to other industrial powers. Ametek’s acquisition strategy seeks such top industry brands, and a common octopus strategy is horizontal expansion. After LAND was acquired by Ametek in 2006, it expanded into combustion efficiency and pollutant monitoring analysis instruments, which is precisely the nourishment that the octopus can provide.

U.S. Meas is a unique player in the sensor field. Although it is not large, with just over 2,000 employees globally, it is filled with acquired brand spoils from Switzerland, Germany, and France. Over the years, it has accumulated more than ten unique sensor brands, including ICSensors, PEncoder Devices, MWS, Atex, etc. The board of MEAS resembles a collector, tirelessly acquiring various sensor brands, falling in love with each one, covering fields such as aerospace and military. It can be said that Meas is a versatile technical expert, adept at expanding product sales depth and skilled at rapidly commercializing technology. Therefore, its acquisition focus often lies in technology assessment. As a result, MEAS has acquired companies specializing in pressure, angular velocity, and other sensors, gaining a wealth of sensor technology, which it commercializes, such as being the first to commercialize linear variable differential transformers (LVDT), the first to achieve batch processing technology for silicon micromachining, and the first to apply glass micro-melting innovation technology to silicon strain gauges. This daring approach to technology has made it a brave pioneer, continuously reaping rewards. After acquiring the technology from Piezo Film, it quickly transformed it into low-cost life characteristic sensors, earning substantial profits. This is a formidable little octopus. Until one day, it encountered a giant octopus. The connector-focused TE Company swallowed Meas whole in 2014. Years of accumulated sensor brands became the claws of the connector giant.

The investment portfolio company Process Insights focuses on instruments for production process analysis, control, and safety, with eight brands that are leaders in various niche industries. Compared to other behemoths, it is more compact, possessing the most core sensor technologies. Through the acquisitions of these eight companies, Process Insights has essentially completed the puzzle in the field of process gases and water analysis. Interestingly, this is an investment company that has become a leader in instrumentation through buying. This inevitably reminds one of the global process automation giant Emerson, which also transformed itself into an automation brand through a series of acquisitions.

Acquiring these small brands is not costly, as these nearly invisible manufacturing wasps are the leaders in their niche industries. For example, Process Insights’ acquisition of MBW is synonymous with the cold mirror analyzer, an essential instrument in humidity measurement. If MBW is seen as the BMW of the automotive field, it is not unreasonable. However, brand influence is merely a single claw of the octopus strategy; more importantly, how brands complement each other, like the coordination between octopus tentacles. For instance, starting from the acquisition of COSA XENTAUR in 2017 to the completion of MBW’s acquisition in December 2020, it formed a product closed loop in the humidity field. Whether it is the most common COSA XENTAUR aluminum oxide capacitive analyzer, the semiconductor electronic optical cavity decay analyzer from TIGER OPTICS, or the cold mirror analyzer from MBW, the combination of the three provides a complete solution for the entire humidity field. This is a combination of three tentacles. If we change to another combination, such as through COSA XENTAUR and ATOM, it can provide a complete set of three instruments for natural gas shipping, including calorific value analyzers, water dew point analyzers, and total sulfur analyzers. This is a precise coverage of the industry. This is why the octopus needs so many tentacles.

3/ Deterring the Supply Chain

From the perspective of the instrumentation and related sensor industry, there is both competition and cooperation among the major U.S. instrument and sensor companies. However, as a competition between nations, it forms an absolute advantage over other countries.

Reducing the technological monopoly formed by independent small brands also ensures the profits of large companies. A typical example is the cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS) analyzers in electronic gas products, which are currently only used on a large scale by four companies globally, three of which are subsidiaries of large U.S. companies: Picarro, TIGER OPTICS (part of PST Group), and LGR (part of ABB Group). They monopolize most of the domestic and international markets, while domestic companies OptoEnergy Technology and Hesai are far behind.

When the octopus swallows small brands, it often uses control over sensors to restrict competitors in the instrument sector. As the largest aluminum oxide sensor manufacturer in the U.S., COSA XENTAUR also supplies sensors to other instrument giants like Panametrics, Teledyne, and Servomex, with very few international market competitors. For the parent company Process Insights, if it wants to suppress the market share of the other three instrument manufacturers, it only needs to cut off the supply of sensors, which would put competitors at risk of production stoppage. Moreover, it can use patent barriers and other means to ensure that these instrument manufacturers do not expand into this field, increasing its own bargaining power and leverage.

Companies like Panametrics, although they may have their reservations, have no choice but to use COSA XENTAUR’s humidity sensors and will not easily develop their own. On one hand, this is due to patent barriers, and on the other hand, it is because they are not adept at sensor development. The least favored aspect of sensors is that results can only be achieved through long-term research and development, and the R&D costs do not proportionately yield results. A sensor that has not been refined over ten years is unlikely to be considered technically mature.

Through the octopus’s outreach, it can open channels and comprehensively enhance product competitiveness. For instance, Thermo Fisher Scientific acquired several companies in 2016, including AFFYMETRIX (chip manufacturing), INEL (X-ray), and FEI (electron microscopy). Affymetrix is a well-known biotechnology company. Its chips include: RNA expression analysis (expression profile chips), SNP detection (genotyping), copy number variation (CNV), small RNA, methylation, and various other chips, which have strong competitiveness in their niche fields. INEL, established in the 1980s, has a series of XRD instruments, capable of handling everything from conventional desktop instruments to complex analysis platforms for nanomaterials and pharmaceuticals. As for FEI, with a 60-year history, it holds a leading position in electron microscopy and imaging systems, with only a few competitors like Hitachi and Zeiss. It is these top companies in the industry that support Thermo Fisher Scientific’s revenue of 170 billion RMB.

4/ Sometimes They Get Entangled

Of course, the octopus’s tentacles can sometimes get tangled. The cost expenditures caused by these business acquisitions and expansions can lead to two problems: one is the price increase behavior of the new owner; the other is internal cost reduction through layoffs, but this often results in cutting R&D teams, leading to insufficient product momentum.

A typical example is the Panametrics ultrasonic measurement instrument, which was acquired by GE Energy in 2002 and has remained silent since, now belonging to GE’s Baker Hughes company. Meanwhile, COSA XENTAUR’s sensor and instrument division, after being acquired by Process Insights, has hardly launched any new products. Existing product prices have increased by about double over the years, leading to a very poor user experience and customer attrition.

Organizational restructuring can also bring new troubles, such as layoffs leading to technology leaks. A typical case is the global process measurement company PST Group, which, after acquiring the British dew point instrument manufacturer Michell, along with subsequent acquisitions of AII and Rotronic, has become a comprehensive sensor giant. However, this has also produced adverse consequences; Michell’s personnel, in 2014, re-established the dew point instrument company Stork Instruments, creating a formidable competitor for PST Group. The reason is simple: Stork Instruments was directly founded by Michell’s founder, and its products have a high degree of overlap with Michell’s. Mr. Michell, as the inventor of the ceramic aluminum oxide capacitive sensor, is well aware of the strengths and weaknesses of sensors. The dual ceramic capacitive sensor and beam-splitting reflective dew point meter launched by Stork Instruments pose a lethal threat to Michell’s product line. In simple terms, the second child that the founder left home is devouring the kingdom of the first child. FirstSensor is a key sensor supplier for differential pressure transmitters in the Chinese petrochemical field, and after being acquired by the connector company TE in 2019, it has caused significant panic in China. This poses a huge threat to Chinese differential pressure transmitter instruments. Many former employees of FirstSensor may become a new source of technical replacements.

Another issue is the parent company’s control over sub-brands. After acquisitions, the treatment of sub-brands varies. Some companies retain core personnel, only controlling financial and key position appointment strategies. Others dissolve all business and logistics personnel, retaining only the most essential production-related staff. In terms of after-sales costs, groups tend to be harsher on sub-brands, trying to minimize service personnel, leading to longer response times and poorer crisis management capabilities.

There are also claw-cutting behaviors. To ensure profits, the parent company may sell off sub-brands that do not meet profit expectations. Some brands, after multiple transfers, experience significant personnel changes and ultimately nearly disappear from the market.

5/ Three Moats to Defend High-End Manufacturing

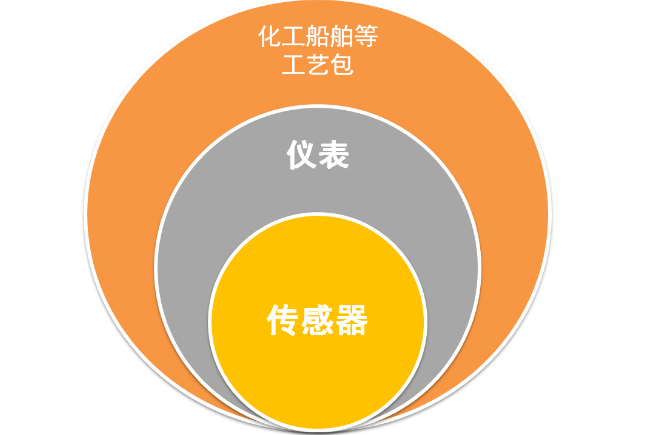

How do American companies defend high-end manufacturing? In the field of instruments and sensors, the giant octopus strategy has already formed two defensive supply chains.

Behind these two supply chains, there is also a third defensive chain, which is the penetration of processes in large industries. For example, in the chemical and shipbuilding fields, whether in design or operation, the industry knowledge and professional process packages involved give U.S. companies significant influence, making it easy for them to exert pressure on buyers. For instance, when purchasing a set of natural gas production lines designed by U.S. companies, the recommended supporting instruments for such projects will certainly not escape the grasp of several American brands.

Figure 3/Three Defensive Supply Chains

The abundance of cross-disciplinary talent and deep application markets is also a significant advantage for the U.S. in developing instruments. For instance, the high demand for expensive instruments and sensors on military ships and aircraft allows companies like Teledyne to maintain a wide variety of instrument types. Talents in areas such as chromatography, mass spectrometry, spectroscopy, and electrochemical sensors are abundant, creating a synergistic effect of 1+1>2. Talent and the three-layer industrial chain moat allow the U.S. to firmly hold its ground in high-end manufacturing.

From sensors to finished instruments, and then to large application scenarios, the interconnected chain allows the octopus to thrive freely. This is a comprehensive national supply chain offensive and defensive strategy.

The comprehensive competition of U.S. companies against instrument companies in other countries and regions creates significant spatial pressure. For example, the British Shaw company can only specialize in specific fields like dew point temperature instruments, facing the risk of malicious acquisition. To compete with U.S. companies, companies in other countries have also strengthened acquisitions, such as Germany’s largest sensor manufacturer SICK, which, after acquiring Maihak, has both sensor and analytical instrument departments. In 2014, it also acquired Micas radar sensors to enter the mining field. It even acquired the assets of the largest American analytical instrument manufacturer PerkinElmer in Germany. This sensor company, with an annual output value of 13 billion RMB, is a rarity in Germany’s traditionally small but beautiful sensor market, and its series of acquisitions have secured it a place in the octopus club. Meanwhile, the largest British instrument manufacturer, Spectris, has adopted a similar octopus strategy, with its frenzied acquisition activities being no different from its American counterparts, and even surpassing them. Its recent series of acquisitions in automotive simulation software have been truly remarkable.

Figure 4/The Octopus Strategy of the UK Spectris

It seems that the octopus strategy adopted by the U.S. instrumentation industry will become one of the important business models in the future.

6/ A Note: The Wind Rises and the Sails Depart

Through years of development and acquisitions, the aircraft carrier formation of U.S. instruments and sensors has been established. The octopus strategy has established an absolute advantage. Meanwhile, in China, the instrumentation and sensor industry is still in the gathering stage of sailing ships. China’s manufacturing is large but not strong, and the instrumentation industry is not even considered large, it can only be said that numerous but not substantial. Domestic leaders in instrumentation are merely a fraction compared to foreign manufacturers. Even with such a scale, it still grows on the foundation of foreign sensors. Moreover, domestic sensors are even smaller in scale and lack leadership. Coupled with the poor interaction between sensor manufacturers and instrument manufacturers, there is a significant lack of coherence in such octopus strategies. This loose industrial form can neither stabilize the industry nor expand territory. As the intelligent society undergoes significant development, China’s instrumentation development strategy still needs careful refinement.

END.

Contact Us: xtydqi001 (Duty WeChat)

Advertising and Business Cooperation: Phone 15053167995 WeChat qqmm-777

Submissions and Interview Arrangements: Email [email protected]

Copyright Statement: The manufacturing community, in addition to publishing original articles, is also committed to the exchange and sharing of excellent articles. Reprints must indicate the source and author; for reprint authorization, please leave a message at the end or in the background. All rights reserved, and violators will be held accountable.