Original authors: Minshen Zhu & Oliver G. Schmidt

The key to reducing the size of electronic devices lies in improving material performance and optimizing device architecture.

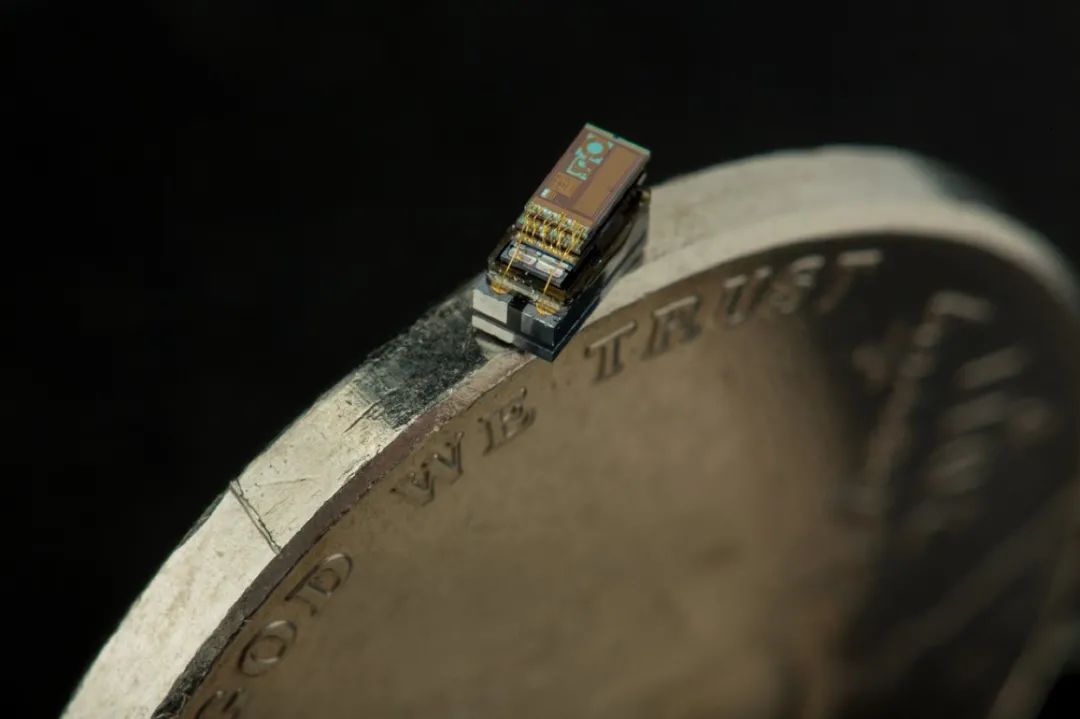

Smart dust is about to enter our lives [1,2]. People are developing computers, sensors, and robots the size of salt grains that can move around, detecting light, sound, pressure, chemicals, and magnetic fields. These tiny devices are often less than a millimeter long and only a few hundred microns thick, capable of processing information and communicating wirelessly. The applications of smart dust are vast, ranging from medical diagnostics and surgical procedures to brain monitoring and tracking butterflies and crop conditions.

But how do we power them? Currently, the smallest batteries have an area of about 2 square millimeters [3], which is several times larger than the smart dust chips. Moreover, the energy stored is insufficient to continuously drive the complex functions of the entire device. Therefore, smart dust chips must rely on external power sources, such as solar panels, which do not work at night or on cloudy days.

Batteries undoubtedly need to be miniaturized, but smaller spaces make it challenging to accommodate all components. These components need to be made into micro devices rather than simply being tied together. This is similar to achieving what Tesla is working on at a much smaller scale: integrating the electric vehicle battery with the car. However, regardless of size, the technologies used to manufacture batteries and electronic devices are different.

For example, small batteries like lithium-ion batteries are made using wet chemical methods (for example, applying slurry to metal foils). We can improve performance by adjusting the material composition, but the extent of improvement is limited.

Source: Martin Vloet/D. Blaauw, D. Sylvester & H. Kim/Michigan Micro Mote (M3)/University of Michigan

In contrast, microelectronic engineers use methods such as etching and deposition to sculpt semiconductor wafers for specific functions. However, this method is not suitable for battery materials. Micro batteries require a completely different design.

The emergence of micro batteries requires two prerequisites: first, high energy density and durable materials to improve charge storage; second, a clever architecture that can miniaturize and combine components.

As nano-scientists manufacturing micro devices, we are well aware of how difficult it is to combine electrochemistry and microelectronics. These disciplines have previously developed independently. Microelectronic engineers often struggle to integrate new materials such as active polymers into their production processes, encountering cross-contamination and mismatches in thermal and electronic performance. Meanwhile, battery and materials scientists often settle for optimizing materials based on one parameter without considering their overall utility in devices and circuits. This is why our lab has established a cross-disciplinary team that encompasses all these research directions.

Here, we call for electrical engineers, battery scientists, and polymer scientists to collaborate more closely to overcome these issues. We need to place more emphasis on redesigning battery structures, materials, and manufacturing methods. We also urge funders and universities to cultivate more scientists with interdisciplinary research skills to prepare for the next generation of microtechnology.

Four Paths

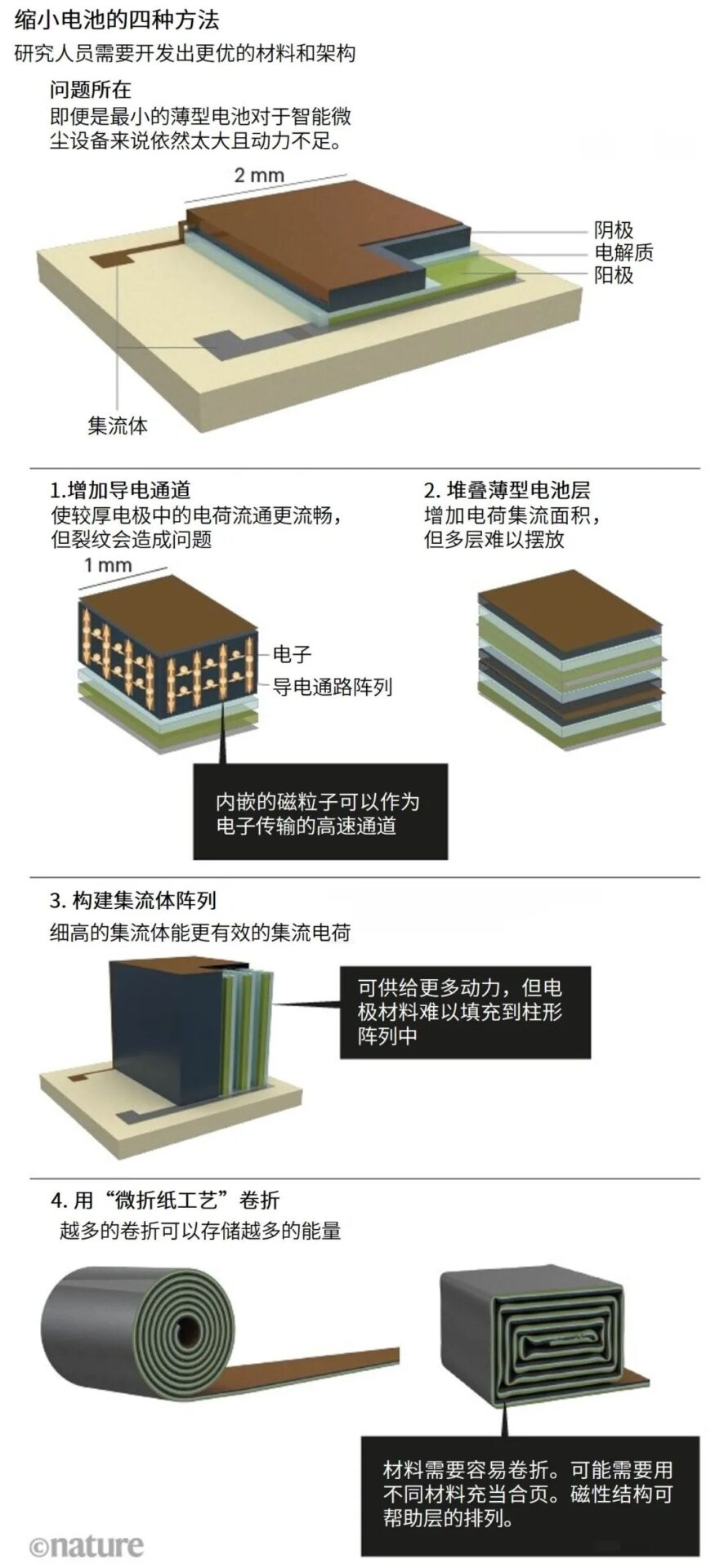

Batteries are essentially multi-layered sandwiches. Two electrodes store electrical energy in the form of chemical energy. Charges can be transferred between the electrodes via an electrolyte without causing a short circuit. The metal current collectors connected to the two electrodes are responsible for guiding charge transfer to the external circuit. However, the smaller the electrodes, the less charge they can store. The presence of cracks and other defects may block electron flow, leading to battery failure. Thicker material layers can hinder ion and electron transport, increasing electrode resistance.

To overcome these issues, the smallest batteries are extremely thin. Their power is also very limited, with an energy density per unit area of only about one-eighth that of a one-centimeter-sized button lithium-ion battery. A film battery with an area of 2 square millimeters and a thickness of 150 microns can power a simple temperature sensor for two days, but for data transmission, it lasts less than an hour [3].

There are four methods to store more charge in a smaller space (see “Four Methods to Miniaturize Batteries”).

Source: M. Zhu & O. G. Schmidt

First, increase conductive pathways on thick electrodes. Just like lanes on a highway, embedded rows of magnetic particles allow charges to flow smoothly [4]. However, the applicability of this method has not yet been proven at the millimeter scale. Moreover, it is difficult to precisely arrange the particle chains. At the same time, the presence of cracks remains a problem.

Second, stack multiple thin sandwich batteries together. This architecture allows for smooth charge flow. However, stacking many layers of batteries is inherently challenging, not to mention keeping them aligned. For example, the high temperatures required to anneal one electrode layer may damage other electrode layers. Additionally, some materials may not be suitable to be placed on top of others, and this incompatibility may grow with the stacking. Furthermore, the presence of defects may lead to short circuits between electrodes.

Third, redesign the current collectors. Designing current collectors in a cylindrical shape rather than a flat sheet increases the contact area between electrodes and electrolytes, thus improving battery power. Constructing such fine structures in three-dimensional space is feasible, such as etching them onto silicon wafers. However, this requires adding extremely cumbersome extra steps, such as coating electrode materials to assemble the entire device. This design has not yet been realized at the microscopic scale.

Fourth, use the “micro origami method” to roll up film batteries. At larger scales, rolling can be done manually [5]. In commercial block or cylindrical batteries, folding or winding machines are typically used. However, at the millimeter scale, this can be achieved through self-assembly. We can make the film roll itself by applying and releasing tension. Our team has utilized this method to create a micro capacitor by sandwiching dielectric films between metals [6]. However, just like rolling up a poster, it is challenging to ensure that the film remains aligned after rolling it several hundred times. Using magnetic fields to guide can solve this problem: by adding a small amount of magnetic material to the battery film and applying a magnetic field, it can keep its order. While we have confirmed the feasibility of this method with micro capacitors, battery stacks are typically thicker, and their mechanical behavior is much harder to predict, making handling them much more difficult.

Folding is even more challenging. Just like folding paper multiple times, the increasing stack requires greater and greater force to fold. The turning points may also develop cracks due to pressure accumulation. The self-folding process needs to consider all these details, such as integrating different materials into the hinges. Even so, it is still difficult to align all layers and components.

Folding a film battery 30 times can fit into the smallest computer (0.14 square millimeters) and is expected to provide at least 100 days of power on a single charge. Many smart dust devices will require more powerful batteries, possibly needing to be folded several hundred times.

Improving Materials

Micro batteries also need more advanced materials to make the films as thin as possible, facilitating the micro origami process and enhancing charge storage. Lithium-ion batteries and aqueous zinc batteries are currently at the forefront of development. The challenge lies in how to make them compatible with semiconductor technology.

In lithium-ion batteries, cathode materials (usually metal oxides, such as lithium manganese oxide and lithium cobalt oxide) can be operated at micro sizes through etching or removing excess material. Anodes (usually graphite) and electrolytes are more challenging to handle, as electrolytes are typically liquid organic compounds in matrices or membranes. Solid electrolytes are also an option; however, ceramics are brittle, and lose conductivity once they become too thin. Polymers can be shaped, but this process (such as ion etching and photopolymerization) must be finely tuned, such as establishing links that easily form or break between polymer molecular chains. Other methods, such as spin-coating or vapor-depositing polymer electrolytes, also need optimization. Furthermore, the conductivity of polymer electrolytes still needs to be improved to match that of liquid electrolytes.

Additionally, better-performing anodes need to be developed. Silicon anodes and lithium anodes are currently being researched, but their stability needs improvement. Silicon reacts with lithium, expanding in volume as the battery charges, ultimately leading to fracturing. This drawback can be avoided through nanotechnology. For example, by wrapping silicon in graphene nanosheets and using polymers to slow or inhibit volume changes. Of course, these solutions must also be adjusted to fit chip manufacturing.

Anodes made of metallic lithium also have short lifespans. Lithium electrodes consume and rebuild during battery operation and charging, but this process is not completely reversible, leading to gradual loss over hundreds of cycles. Therefore, better management of the fine processing of lithium is needed. One method is to avoid using metallic sheets and effectively form lithium electrodes again during charging using ions in the electrolyte. This type of battery can cycle 80 times on a 5 square millimeter chip [7]. However, this is still far from the 5-25 years of service life required for implantable medical devices.

The electrodes of aqueous zinc batteries also need optimization. Zinc, as an anode, can effectively store and release ions. Aqueous zinc-ion batteries perform better when using acidic electrolytes compared to typical alkaline electrolytes. However, zinc will dissolve in acid and release hydrogen. Therefore, the anode must have a protective anti-corrosion layer, or the electrolyte needs modification to reduce its proton release capability. Similarly, the cathode (typically made of metal oxides such as manganese dioxide and vanadium pentoxide) is also susceptible to acid and requires a protective layer.

Aqueous batteries need to operate at higher voltages—above 2V, water decomposition reactions occur. This reaction consumes the energy of the battery and is a challenge that must be addressed in aqueous battery research. To this end, it is necessary to explore all intermediate ions involved in the load (including H+,Zn2+,Mn2+, andOH−) and their interactions with electrode materials [8]. Polymer-based electrolytes may provide some buffering to prevent water decomposition.

Other batteries are also emerging, such as magnesium, calcium, potassium, and sodium-ion batteries. The technology for these batteries is not yet mature enough for manufacturing micro batteries.

Next Steps

Materials and microelectronics researchers need to learn from each other. It is indeed frustrating when a material performs well in the lab but cannot achieve that excellent performance in actual devices. What we need to do is visit each other’s labs, spend a few days designing and fabricating each other’s technology prototypes, and understand the challenges faced by one another. For instance, how can polymer electrolytes withstand the wet chemical processes that form metal layers on them? The synthesis of materials on chips at specific locations and layers within battery packs also relies on the development of new processes.

Materials-related conferences, such as those held by the American Materials Research Society, the American Chemical Society, and the American Physical Society, should invite electronic engineers to participate in energy storage-related conference topics. Electronics conferences, such as the International Semiconductor Technology Symposium on Very Large Scale Integration, should invite materials scientists to share their cutting-edge battery chemistry knowledge. One goal is to establish a joint roadmap for micro battery performance and target specifications.

Computer modeling will be essential, aided by machine learning algorithms [9]. Experimental optimization of structures and materials is needed. Any changes in materials (crystallinity, thickness, and synthesis routes) will alter the mechanical and stability properties of the films, thus affecting their folding behavior. Additionally, there is a vast amount of work to be done to optimize every parameter of the batteries (such as strain or battery chemistry). Designers also need to understand how electrochemical and mechanical properties affect the self-assembly process.

We need to develop plans to generate and share reproducible data on batteries and micro devices. The Illinois Energy Storage Research Consortium and the European Battery 2030+ initiative have facilitated collaboration toward next-generation batteries, including smart functionalities, durable materials, and industrial manufacturing.

Universities need to establish interdisciplinary courses in materials chemistry and microelectronics technology. Funding support should be jointly provided by both fields. China is rapidly moving in this direction. This August, the Ministry of Education of China established an interdisciplinary program combining electronics, engineering, materials, chemistry, and physics alongside single disciplines like natural sciences. The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology is a world-leading research institution that has set up a new campus in Guangzhou, China, with an investment of over $2 billion. This campus will follow a hub model. For example, functional centers will combine materials and microelectronics knowledge to facilitate the integration of micro-nano devices into multifunctional components. At Chemnitz University of Technology in Germany, one of the authors (O.G.S.) is teaching a similar course called “Materials for Micro and Nano Technology.” It combines knowledge from photonics, electronics, biotechnology, micro-robotics, and energy storage to prepare students for future involvement in complex microsystem engineering.

Through the collaborative efforts mentioned above, micro batteries will pave the way for imperceptible, ubiquitous computing within the next decade.

References:

1.Wu, X. et al. 2018 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Circuits 191–192 (2018).

2. Piech, D. K. et al. Nature Biomed. Eng. 4, 207–222 (2020).

3. Lee, Y. et al. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 48, 229–243 (2013).

4. Li, L., Erb, R. M., Wang, J., Wang, J. & Chiang, Y.-M. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1802472 (2019).

5. Song, Z. et al. Nature Commun. 5, 3140 (2014).

6. Gabler, F., Karnaushenko, D. D., Karnaushenko, D. & Schmidt, O. G. Nature Commun. 10, 3013 (2019).

7. Oukassi, S. et al. 2019 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM19573.2019.8993483 (2019).

8. Zhong, C. et al. Nature Energy 5, 440–449 (2020).

9. Aykol, M., Herring, P. & Anapolsky, A. Nature Rev. Mater. 5, 725–727 (2020).

The original article titled “Tiny robots and sensors need tiny batteries — here’s how to do it” was published in the review section of Nature on January 13, 2021.

© nature

doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00021-2

Click to read the original article to view the English original

Recruit

Job

Job Recommendations

Nature Careers

1. Center for Life Sciences

Job Position: International Researcher Program in Life Sciences and Related Interdisciplinary Fields (Junior Postdoctoral Researcher); Beijing

Apply for the position before October 10, scan to view details →

2. BioTech

Job Position: (Deputy) Director and R&D Staff of Mobile Wearable Device Research Institute; Beijing

Apply for the position before October 11, scan to view details →

3. Nanjing University

Job Position: Faculty in Chemistry, minimum annual salary of 400,000 yuan, Nanjing

Apply for the position before October 12, scan to view details →

For more domestic and international research job opportunities, please visit: nature.com/naturecareers

Click the image to see how to self-publish job postings through Nature Careers (nature.com/naturecareers) platform