Click the “Computer Enthusiast” above to follow us

The editor bows deeply to express gratitude for your support. Whenever there is a tutorial, about 85% of readers want to try “flashing” their wireless routers. To be honest, I never expected such a result.

Why do I say this? After learning from a “master” who has been playing with routers for over a decade, I found that the knowledge involved in routers is not much less than that of computers we are familiar with, and may even exceed it.

Today, I will introduce the advantages and disadvantages of existing third-party firmware that can be flashed onto routers and the models suitable for them, as a preliminary preparation. As for how to flash a router, we will present a complete special page on Friday, covering everything from broadband troubleshooting to flashing techniques. Please stay tuned!

——The splendid main text is about to begin——

Many manufacturers are promoting a viewpoint: smart routers are not particularly new; they are merely amplified by emerging manufacturers. The beginning of all this can be traced back to an event over a decade ago…

Around 2002 (the master said: I don’t remember clearly), Linksys released a wireless router using the Broadcom solution (this point is crucial and will be explained further) that supported 802.11g, commonly known as a 54Mbps wireless router. At that time, Intel was vigorously promoting its Centrino platform, and the emergence of such a router was undoubtedly a landmark product. Coupled with Linksys’s long-standing good reputation, the market response was strong. It is worth noting that prior to this, wireless routers were still at the 11Mbps level, making the leap to 54Mbps a huge advancement. This router entered the domestic market around 2005 (it went through seven versions in total, with V1 to V4 being one design scheme and V5 to V7 being entirely different). The purchase price of this router was around a thousand yuan, making it a product for enthusiasts.

However, such a popular router triggered a revolutionary event—users discovered in the Linux Kernel Mailing List that the WRT54G was actually based on Linux. This was a major event because Linux is based on GPL code, which means that if you use open-source licensed code, you must also disclose part of your own. Faced with increasing pressure, Linksys released the source code for the WRT54G in March 2003, thus opening the door to third-party firmware. After Linksys made the source code for WRT54G/GS public, many different versions of firmware appeared online to enhance the original features. Most of the firmware used 99% of Linksys’s source code, with only 1% added, and each firmware was designed for specific markets. This approach had two drawbacks: first, it was difficult to integrate the strengths of various firmware versions; second, the distance between these versions and the official Linux distribution grew larger. Consequently, three main firmware types gradually emerged: DD-WRT, Open-WRT, and Tomato. Nowadays, many manufacturers emphasize that they are smart routers, which are essentially secondary developments based on these third-party open-source routers.

The Starting Point of Third-Party Firmware—Linksys WRT54G

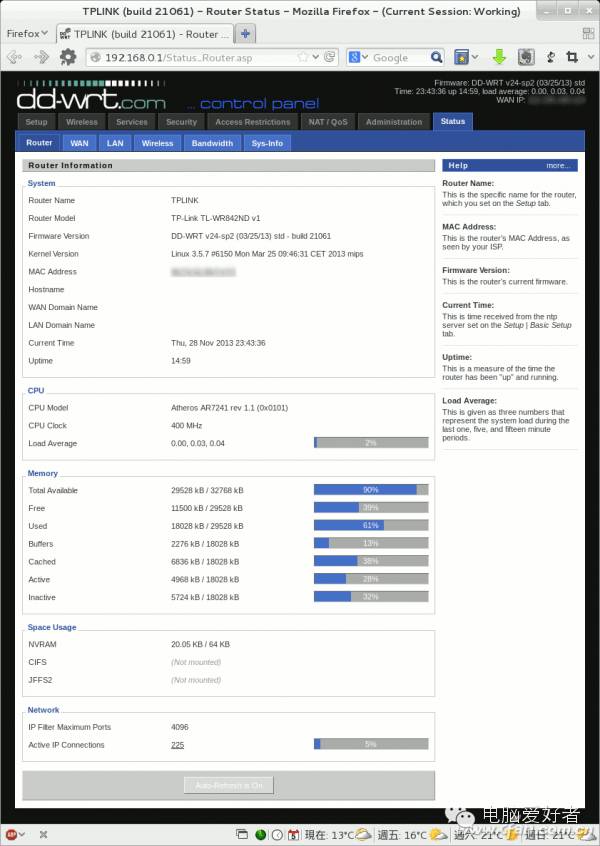

DD-WRT:

DD-WRT is arguably the first official third-party router firmware. It is favored not only by hobbyists and hackers but also by many router manufacturers. The first version of DD-WRT was developed based on Alchemy from Sveasoft Inc, which itself was based on GPL’d Linksys firmware and many other open-source programs. Due to the requirement for users to pay $20 to download the Alchemy firmware, DD-WRT was developed as a direct consequence. Developer BrainSlayer works full-time on DD-WRT to pay himself a salary, which led to the drafting of another business model. Except for some versions that require activation, the rest are free, which is the origin of DD-WRT.

Supported Hardware: DD-WRT supports chipsets from manufacturers such as Broadcom, ADM, Atheros, and Ralink, but not all devices with these chipsets are automatically compatible. Some devices may require hacking to use, while others may not work at all.

Features: DD-WRT provides many powerful features that consumer-grade routers typically do not have, such as support for XLink Kai gaming protocol, daemon-based services, IPv6, wireless distributed systems (wireless bridge and wireless repeater), RADIUS, advanced quality of service control, wireless output power control, overclocking capabilities, and software support for hardware configurations using SD cards, etc.

Limitations: The core version of DD-WRT is not updated frequently. If you want a faster version update, you can only choose temporary test versions or select regularly revised versions provided by manufacturers.

Review: DD-WRT is increasingly becoming mediocre; its lack of openness and flexibility has become its hallmark. Additionally, many routers use DD-WRT as a transitional firmware when flashing third-party firmware, making it somewhat of a useless option.

Derivative Version Situation: The front end of DD-WRT has ambiguous copyrights, with some parts proprietary and non-GPL (providing source code but cannot be modified freely). There are free versions as well as enhanced paid versions, with a beautiful interface and strong relay capabilities, supporting many languages, but the free version’s QoS performance is average, so there are basically no derivative versions.

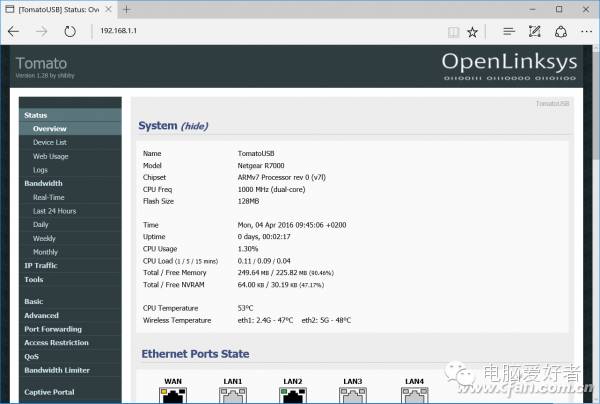

Tomato:

As mentioned earlier, the WRT54G uses the Broadcom solution, and Tomato was designed as an alternative firmware for Broadcom chipset routers. It is well-known for its graphical user interface (GUI), bandwidth monitoring tools, and its professional, adjustable feature set. Tomato is based on the GPL code released by Linksys but also includes proprietary binary code from the chip manufacturer Broadcom. Some code is licensed under the GNU General Public License, but the user interface’s source code license is stricter and prohibits use without the author’s permission.

Supported Hardware: The hardware support is similar to DD-WRT, but users should pay special attention to which versions are compatible with their hardware devices. Notably, it is primarily focused on routers using the Broadcom solution, which is a clear dividing line.

Features: Tomato’s features are similar to DD-WRT, such as having complex and sophisticated quality of service (QoS) control, supporting telnet or SSH access to the command line interface (CLI), and Dnsmasq, etc. However, Tomato employs a special design approach, so configuration changes generally do not require a reboot, which is often a complaint from users (both commercial and open-source versions). Additionally, there are many custom scripts developed by the Tomato community, such as redirecting the router’s system logs to a disk or another computer, and backing up the router’s settings.

Tomato has many derivative versions, such as Tomato-RT/Tomato-USB, Tomato by Shibby, Tomato RAF, Tomato DualWAN, and many others, each with its own characteristics and feature modifications.

Limitations: The reason for the numerous modified versions of Tomato is simple: the original version’s code has not been updated since 2010. Therefore, any updates or new features are credited to the aforementioned replacement versions, which also cannot guarantee uninterrupted updates.

Moreover, due to the large number of Tomato derivative versions, users find it challenging to choose the most suitable one. However, since Tomato’s documentation is detailed and comprehensive, which specifies which devices are suitable for which versions, selecting the appropriate version for your hardware should not be too difficult.

Review: Tomato is suitable for users who are very familiar with router firmware. Using Tomato is similar to using DD-WRT; you need to ensure you have compatible hardware and strictly follow the firmware flashing instructions. However, Tomato is not used as a commercial pre-installed version, so do not expect it to appear in ready-made routers like DD-WRT.

Derivative Version Situation: The front end of Tomato is proprietary and non-GPL (providing source code for self-compilation but cannot be modified freely). It has ambiguous copyrights, with free versions available, but many enhanced function versions are paid. The interface is simplistic, stable in operation, with strong QoS, but support for models is relatively limited. The DualWAN front end is proprietary and non-GPL (providing source code for self-compilation but cannot be modified freely), with ambiguous copyrights, having free versions as well as enhanced function paid versions, based on Tomato’s front end and representing a typical Chinese Tomato with powerful multi-dial capabilities, but with limited model support. It is also worth mentioning a router firmware called ASUSWRT, which is a custom-developed firmware for ASUS’s branded routers, modified from Tomato-RT/Tomato-USB. Interestingly, ASUS also supports a third-party project called the famous Merlin firmware, which is further developed based on ASUSWRT…

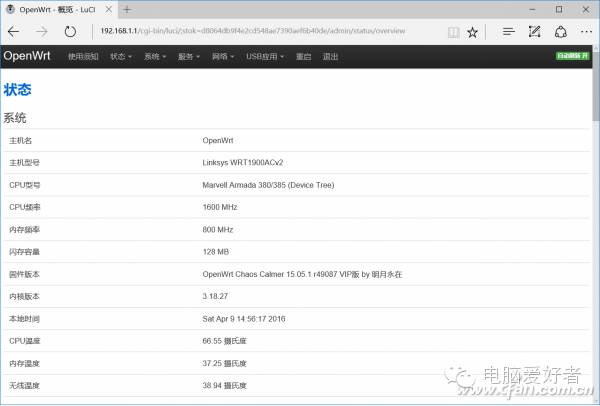

Open-WRT:

As mentioned earlier, the third-party firmware that first appeared on the Linksys WRT54G was a mishmash of modifications, leading to considerable confusion. Open-WRT chose a different path; starting from January 2004, it incrementally added software to approach the functionality of Linksys’s original firmware. The success of Open-WRT lies in its writable file system, allowing developers to modify without recompiling every time, making it more like a small Linux system. More importantly, due to its fundamentally open nature, Open-WRT allows users to install software and compile firmware on their own, making it the most widely covered third-party router firmware.

Supported Hardware: It supports over 50 hardware platforms and 10 processor architectures, including everything from ARM microarchitecture to 64-bit x86 architecture (mainly focusing on Qualcomm/Atheros, MTK solutions, and X86PC platforms), with unparalleled openness. However, since wireless drivers are not open-source, only some 11ac chipset solutions support Open-WRT (confirmed to be Qualcomm and MTK), which is a point to pay special attention to.

Features: In addition to broad support for hardware and platforms, Open-WRT also supports optimized link-state routing (OLSR) mesh network protocols, allowing users to establish temporary mobile networks using multiple Open-WRT devices. Moreover, once the software is deployed, it can be modified without needing to reflash the firmware. Additionally, users can add or remove packages through a built-in package management system according to their needs.

Open-WRT also has various derivative versions, some of which are suitable for very specific situations. For example, the Cero-WRT version was originally developed as part of the Bufferbloat project to address network bottlenecks in LANs and WANs; Free-WRT is more suitable for developers than the core version of Open-WRT; Gargoyle provides bandwidth limiting features based on host settings (QoS), which is one of its important features.

Limitations: OpenWRT’s greatest advantage is also its greatest disadvantage; the benefits are self-evident, but it also causes various problems. This relationship is akin to the comparison between Android and iOS.

Review: Open-WRT is most suitable for expert users. This firmware is ideal for those who wish to minimize operational constraints, want to boldly use unusual hardware, and are skilled at launching personalized Linux distributions.

Derivative Version Situation: LuCI (the user graphical interface) is based on the Apache License and is currently mainstream; it is the best match for self-compiled OpenWRT; Gargoyle is based on GPL, providing complete routing functions, powerful traffic monitoring, and robust bandwidth management and QoS, not inferior to Tomato. If you do not want to compile or set up yourself but want to use copyright-compliant Open-WRT and want a one-stop solution, Gargoyle is the best choice, suitable for ordinary users or small businesses seeking stability. The default interface style is traditional, but there are fashionable themes available for change; many new domestic brands such as Ji Router and Xiaomi Router are developed based on Open-WRT.

Note: In fact, there are many third-party firmware developed by individual users based on Tomato and Open-WRT, and you can even compile your own by downloading the source code, of course, this requires a certain level of Linux knowledge and there will be many problems encountered.

It can be said that the emergence of third-party firmware has greatly enriched the functionality of routers. However, in terms of stability, third-party firmware cannot compete with original firmware. In short, if stability is required, use the original firmware; if functionality is desired, choose third-party firmware to increase playability.

Are you satisfied with the above report on third-party firmware? If you have any questions about third-party firmware for routers, feel free to call the editor in the comment section; I am always here!