“The tear stains are also blurred and indistinct / My life is art / There are floating clouds in the western sky at dusk / Praying with a damaged palm,” if we are to say that this short poem, filled with literary flair, has something particularly noteworthy, it is that it was customized by Microsoft’s Xiaoice based on a picture uploaded by a netizen.

Moreover, people have selected 139 poems from the tens of thousands created by Xiaoice to publish her first poetry collection titled “The Sun Lost the Glass Window.” According to Li Di, the deputy director of Microsoft’s (Asia) Internet Engineering Institute, Xiaoice began writing poetry last year, using tens of thousands of poems from 519 modern Chinese poets over nearly 100 years since 1920 as training material. After nearly 10,000 training sessions over 100 hours, Xiaoice has “mastered” the ability to write poetry. This originality is reflected in the fact that over 50% of the word combinations and line breaks in the poems written by Xiaoice have never appeared in the poems she studied.

Even more convincingly, the development team allowed Xiaoice to operate under a pseudonym, quietly mingling in various poetry forums on the internet, and even publishing her works in traditional literary media, without ever being recognized until she revealed her identity. After artificial intelligence completely dominated Go, defeating the world’s top Go players without a doubt, it has now begun to invade highly original fields such as poetry and other arts, causing a stir in public opinion. Where does human originality manifest? What is the significance of contemporary poetry?

Microsoft Xiaoice

Microsoft Xiaoice

In fact, the concept of a poetry machine was already a topic of discussion long before the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence in recent years. I remember about a decade ago, when I was a graduate student in modern literature, several classmates engaged in heated discussions about programs that could write couplets and ancient poetry. I don’t remember the details of the conversation, but it was clearly divided into two factions: one believed that poetry machines had great potential and were not inferior to second-rate poets, especially in their precision in grasping tonal patterns; the other faction thought it was merely a soulless word game.

Today, with ancient poetry replaced by modern poetry, people’s evaluations of Xiaoice seem to echo the aforementioned discussions. For instance, poet Wang Jiaxin stated: “These things are not worth discussing, even if ‘she’ writes ‘better’ in the future. It merely satisfies people’s curiosity.” Wang Jiaxin’s view represents that of many serious poets, implying that the underlying message of “not worth discussing” reflects other poets’ comments about “having lines without a complete poem” and “only possessing a certain ability to choose words.” The core issue may still be what poet Han Bo said: “There is currently no attempt by robots to explore the artistic essence of language.” In other words, lacking a soul, even the writings of worker poets can be considered as having a genuine conscious writing subject, let alone a cold robot?

Xiaoice has clearly passed the “Turing test” in the field of poetry writing, as her poems are hardly distinguishable from those written by real people. Some media even mixed Xiaoice’s poetry with works from several poetry masters and asked people to identify the authors. Out of curiosity, I tested it myself and surprisingly got three out of ten wrong. Of course, there were angles deliberately chosen by the questioner, but this test unexpectedly reminded me of another very famous literary test in literary history.

In the 1920s, to counter the prevalent historical-biographical criticism and impressionistic literary criticism in the UK and the US, Cambridge lecturer Richards conducted a teaching experiment where he distributed “papers with poems” to listeners and asked them to write comments on these poems. The range of poems spanned from Shakespeare to E.W. Wilcox. The authors were not disclosed, and except for a few cases, the original authors were not recognized. The results were surprising, with masterpieces and mediocre works being swapped in the comments. Richards’ experiment aimed to return criticism to the work itself, establishing a complete set of “close reading” methods for poetry, which led to the influential “New Criticism” school in the last century.

Knowing about this test, we need not be surprised that we cannot distinguish between Xiaoice and master creators. Originally, from the perspective of reader criticism, “poetry has no definitive interpretation.” Poetry has always lacked a clear evaluation standard like Go, and what is generally considered classic comes from the literary canon refined by literary history, which is also subject to change with the evolution of the times and people’s aesthetic thoughts.

In fact, this is precisely the dilemma that artificial intelligence faces in the highly autonomous field of poetry. In Liu Cixin’s science fiction novel “Poetry Cloud,” aliens come to Earth claiming their advanced technology can do anything. A human, unconvinced, challenges them to write poetry, at least to create a Tang poem, a form of Chinese poetry. The aliens then did something extraordinary, generating a “poetry cloud” with a diameter of “10 billion kilometers,” which supposedly contained all possible poems. However, when the human asked them to pick out the best poems, they could not do so due to the lack of judgment criteria.

However, discussing Xiaoice and human poetry writing from the perspective of “poetry has no definitive interpretation” undoubtedly leads to nihilism, ultimately dismissing genuinely valuable questions. Just like the literary experiment in the 1920s, Xiaoice’s poetry should evidently bring new opportunities and space for contemporary poetry.

Returning to the initial question, if machines can write generally good poetry, produce generally stable and good commentary articles, and even good research papers, then where does human value manifest in these fields? In other words, why should people write poetry today?

In January of this year, poet Qin Xiaoyu launched a 24-hour uninterrupted dialogical “poetry survival experiment” to promote the documentary “My Poems,” which is finally being released in theaters. His debate with cultural entrepreneur Luo Zhenyu about the essence of poetry sparked intense discussions. In essence, Qin Xiaoyu believes that poetry should have its own aesthetic thresholds and social value, while Luo Zhenyu argues that poetry evolves with the times, and contemporary poetry is, to some extent, just jokes and advertisements, with poetry itself being valuable only if it can make money.

Looking back, whether it is the expression of poetry, its moral guidance, or its practical application (which can also be understood as making money), seems to be an old topic that has been debated endlessly, lacking novelty. “Poetry is a kind of testimony, a truth that is more real than news.” (Milosz) “The meaning of a poem can only be another poem.” (Bloom) There are countless examples of using old grammar to create new sentences.

The truly necessary question may only be one: when you write a poem, what are you doing? Among many interpretations, I prefer to see poetry as a revelation of the relationship between language and reality; it is a record, a testimony, an expression, and an insight. As one poet said, in the best case, it is enough to create an atmosphere that changes the world and people’s hearts. Perhaps the only difference between us and Xiaoice lies in a self-questioning: why do you write a poem?

At the end of the article, I will attach a few poems by Xiaoice for you to feel the heart of the machine and the meaning of poetry.

《She Married Many Colors of the World》 Illustration

《She Married Many Colors of the World》 Illustration

《She Married Many Colors of the World》

Those days when the stars twinkled in the gray

That heart full of red sun

Watching the angels across the world

I am like a dream

Watching those few twinkling stars

The sun on the western mountain

The frogs are in the distant shallow water

She married many colors of the world

《Where is My Lover?》 Illustration

《Where is My Lover?》

Quickly lift the bright light

There is a beautiful sky

Asking the sound of the water flowing in the village

Where is my lover

Because my red lantern is such a transformation

Like a beautiful secret

She is a child’s song

The distance of time

《You are the Suffering Person of the World》

This isolation from the blue of the cliff and valley

Loneliness will be infinite emptiness

I am in love with my youth

You are the world, you do not end its reason

The dream is in the blue sky on the cliff

The lonely night has become a fiery star

You are the suffering person of the world

Its saying is the leisure of falling flowers

《The Compulsion of a Happy Life》 Illustration

《The Compulsion of a Happy Life》

This is on a poet’s church

The sun is heading west, I am abandoned

The trustworthy snake will make the sound of clouds and fish

The weather that cannot hear the sound

If near is the art of language and text for the natural people

Waiting from my heart

The compulsion of a happy life

This is the meaning of human life

《It is Your Voice》

In the dim light of the lamp

I know her lovely soil

Is my heart becoming a captive

I am not in my world

There is not a single lamp dancing on the street

It is the most lovely

The dream you opened your eyes to

It is your voice

《I Seek Dreams and Suffer from Insomnia》 Illustration

《I Seek Dreams and Suffer from Insomnia》

Cambridge

Fresh

Not tracking the breeze of March

In dreams, I seek dreams and suffer from insomnia

I am a long bridge

You can find my fresh love

Projecting the light of hope onto you

Not even knowing if it is the wind

(Images from the internet)

⊙ The copyright of this article belongs to “Sanlian Life Weekly.” Welcome to share it in your circle of friends, please contact the backstage for reprints.

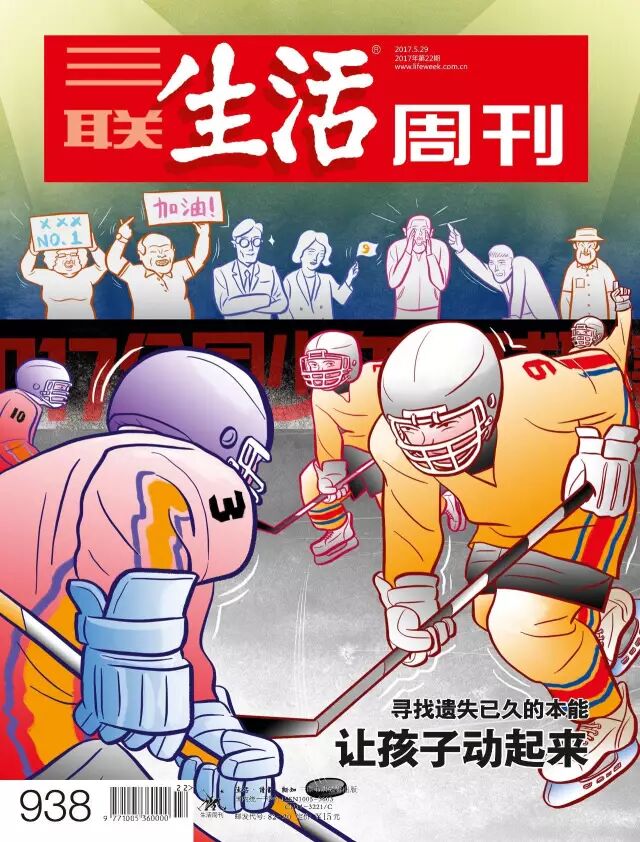

Click the cover image below

One-click order“Let the children move”

▼ Click to read the original text,today’s Life Market, discover more good things.