Part One: Introduction to Urban Construction

Part Two: Nine Principles of 21st Century Urban Design

Part Three: The Future of Cities

~In “Urban Construction: Valuable Experiences of SOM Urban Design (Part One)” we read the first part of the book and the first five principles of the second part. Next, let us continue reading this book~

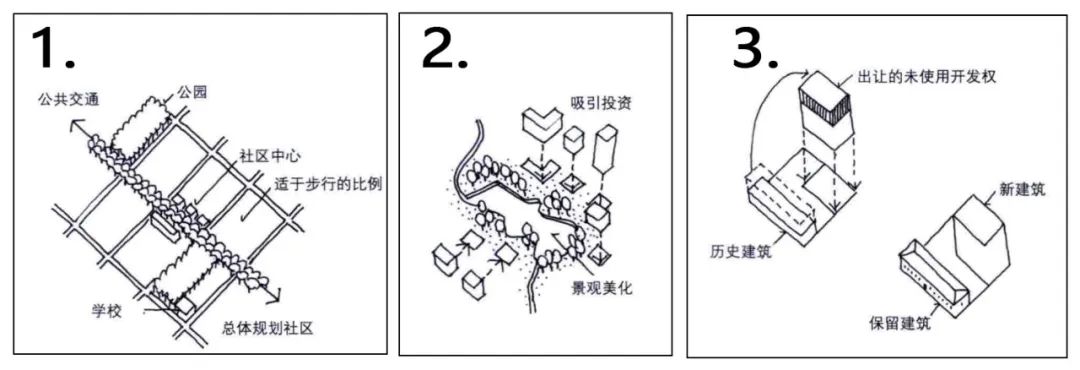

06 Incentive Policies

To achieve reconstruction goals, public incentive policies are often adopted to stimulate new development investments. Among various incentive measures, the most commonly used include:

(1) Tax reductions.

(2) Land cost subsidies.

(3) Site assembly and preparation.

(4) New transportation and municipal infrastructure.

(5) Medical, educational, and public safety services.

(6) Open spaces and landscape beautification.

(7) Additional floor area ratio subsidies.

Moreover, incentive policies should consider the following “overall planning” and “infrastructure optimization” as fundamental elements that jointly determine which incentive measures we need to choose.

In the context of limited resources, a community needs to focus its funds and manpower on development proposals that can yield the highest returns. If consensus is lacking, attention will be diverted to other aspects, making it more difficult to advance projects. Therefore, an effective focus process for overall planning should be established:

1) Development Quality: An approved overall plan, along with design guidelines that provide guidance on transportation, open spaces, and phased construction, serves as a guarantee of confidence for potential investors.

2) Beautification: The landscape beautification of public domains such as streets, parks, and waterfront spaces is a major way to attract development investment. Beautification elements include landscaping, lighting, street fixtures, advertising signs, and directional signs.

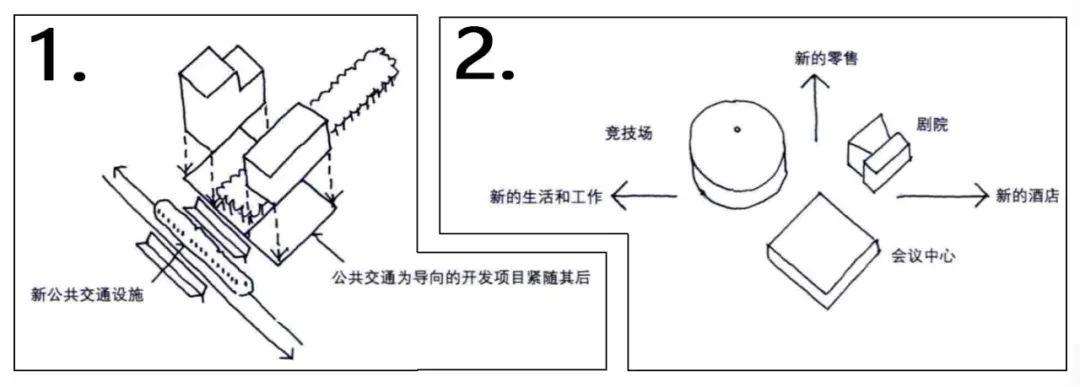

2 Infrastructure Improvement

Two types of infrastructure development can incentivize more private investment:

1) Improving travel convenience: Redesigning public transportation and streets, and constructing new bike lanes, sidewalks, parking lots, and other accessibility improvements can enhance property values within a project and a larger area.

2) Constructing public facilities: New public buildings can create new job opportunities and attract more visitors. They can help promote a city’s economy and happiness index. Investment in public facilities also conveys a positive commitment and confidence towards future transformations to the community.

Case Study 1: Reshaping a River (And Reviving a City) – San Antonio River Walk in Texas

Case Study 2: Rebuilding the Urban Center in a Suburban Context: When Good Intentions Are Blocked – General Plan of San Jose, California

07 Adaptability

Ideal urban design should anticipate that adjustments in project configuration and other aspects are inevitable over time. Ultimately, forward-looking urban construction will form an attractive physical environment framework that allows material elements and functional uses to change continuously while maintaining overall consistency. Therefore, the author discusses adaptability design from the following five aspects:

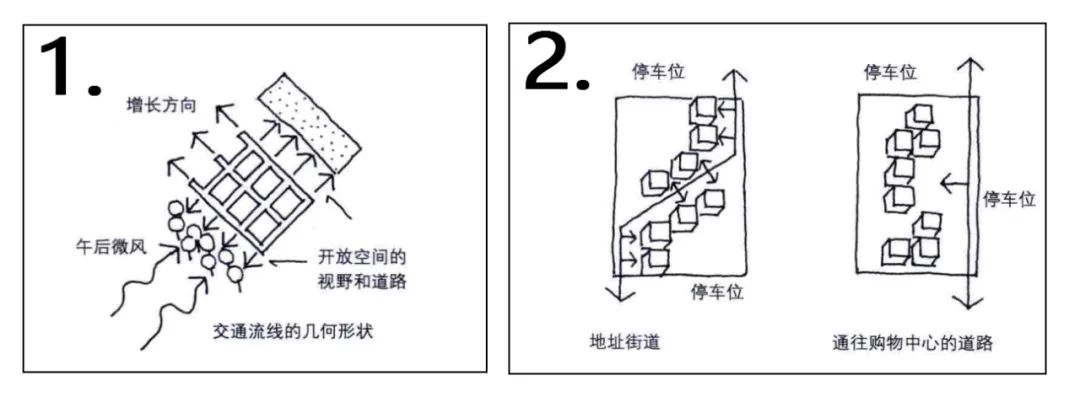

1 Morphological Change

1) Rational Framework: Urban design can be viewed as creating a pedestrian-friendly framework for urban life, organizing traffic flows, open spaces, and ultimately the independent parcels formed by buildings.

2) Parcel Division: Without regulations to subdivide large sites into smaller parcels, people will instinctively place new buildings in the center of any available land. Doing so would lose a significant amount of potential construction sites.

3) Iconic Street Address: Buildings within a large campus or industrial park should not face parking lots. Ideally, they should be set on streets with strong public accessibility, having independent addresses and signs.

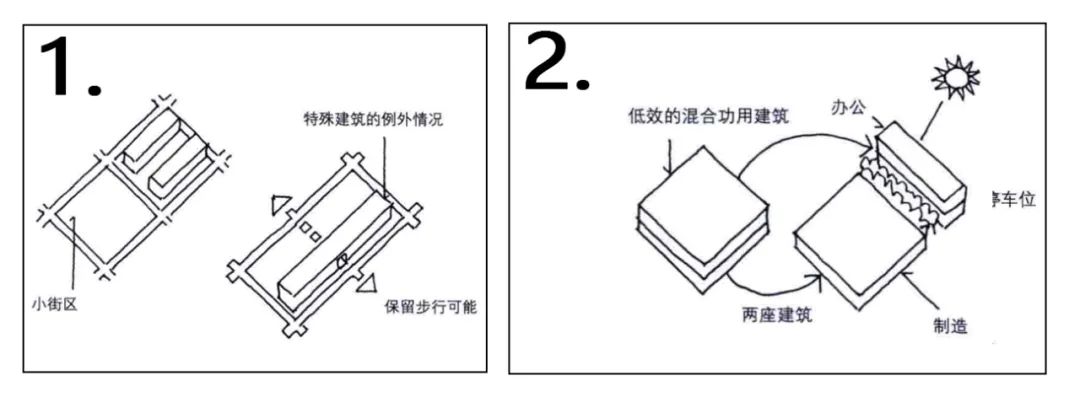

2 Change of Use

1) Sufficient Sites: Generally, smaller blocks should be used as much as possible to create convenient walkability. If large-scale buildings, such as campus medical laboratories, are expected to be constructed, two blocks may need to be combined. For larger blocks, pedestrian pathways should be reserved for crossing internally.

2) Building Adaptability: A building should incorporate flexible elements during the initial design phase to accommodate differences in future tenant needs and changes in use.

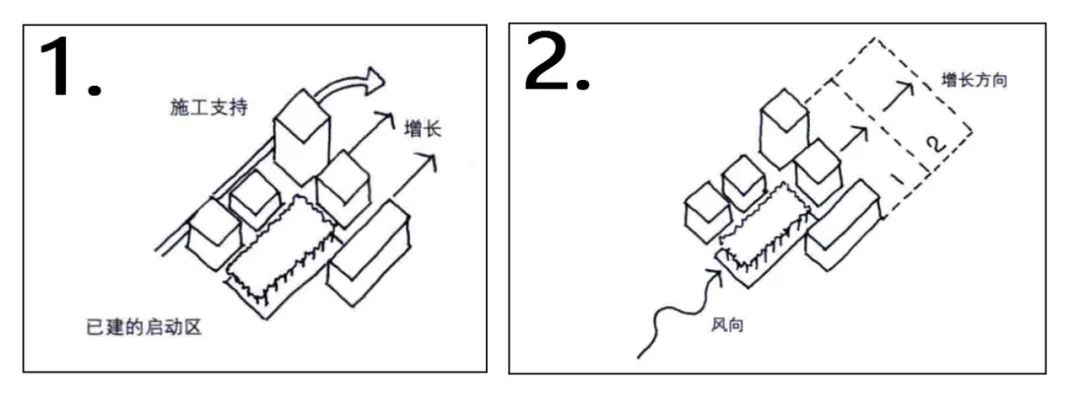

3 Minimizing Construction Disruption

1) Traffic Isolation: Ideally, the site selection for large projects should ensure that construction transport traffic flows away from or around already built areas.

2) Downwind Expansion: Where possible, different phases of large projects should be arranged downwind. This can prevent construction dust, debris, and noise from affecting the built environment.

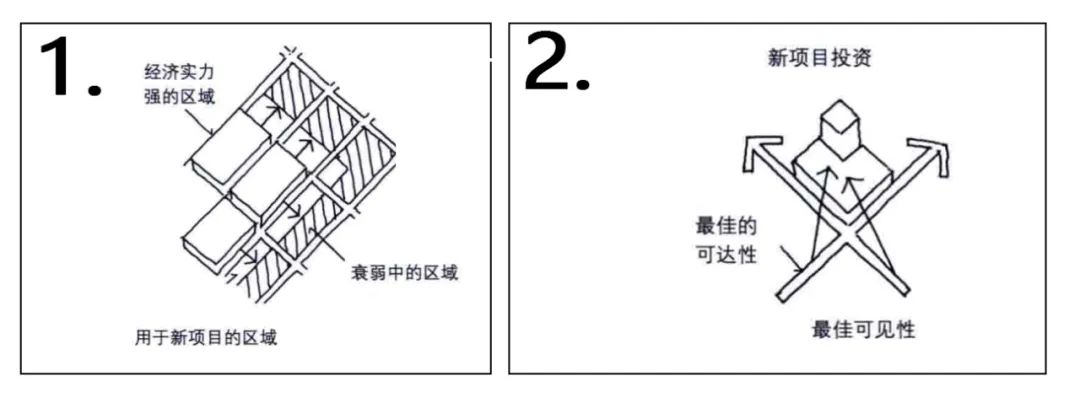

4 Project Location

1) Healthy Surroundings: The project site should be able to utilize the most attractive public facilities and economically thriving areas nearby.

2) High Visibility: A planning project should have good visibility at the neighborhood and larger community levels, as this can help attract tenants, customers, enhance community identity, and become a positive symbol of community renewal.

3) Sense of Completeness: In most cases, a project will only begin construction when there is a sufficient population. The construction of supporting services such as schools or shops must also wait until conditions are ripe. To eliminate the negative impact of vacant lots in this construction pattern, future supporting facilities should ideally be located on the periphery of already built areas. This way, the built environment will have more integrity, and the construction disruption of new projects will be minimized.

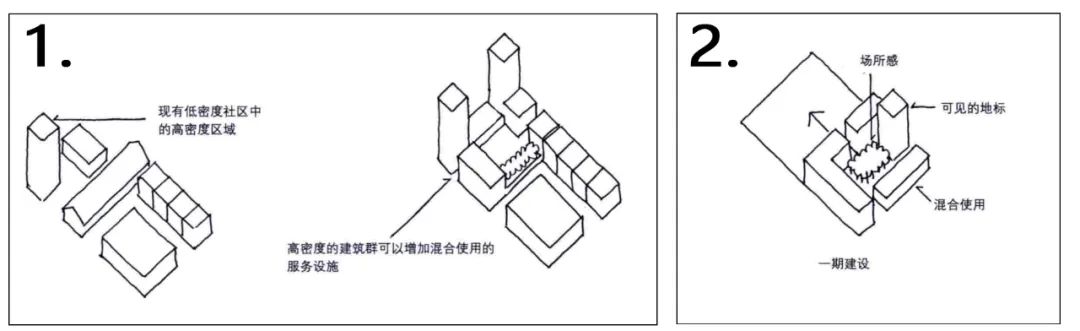

5 Function and Features

1) Economic Strength: A project should have sufficient scale to form the necessary economic strength and appeal to succeed in a particular market.

Of course, building a project in the urban center similar in scale to a suburban shopping center is almost impossible, so more successful cases of reconstruction in the central area come from linking its growth with new residential developments within the central area, adding more “sticky users” to commercial, retail, and entertainment functions.

2) Final Recognizability: In the early stages of a project, advertising, public and media relations, and community meetings should convey intuitive feelings about the project’s final state, mixed uses, design features, and overall quality to potential users, which will help the project gain recognition and success.

Case Study 1: Planning for Continuous Change – Texas Medical Center in Houston

Case Study 2: Guiding and Predicting Development Through Design Principles – University of California, San Diego (UCSD)

Case Study 3: Recovering Diamonds in the Rust Belt – Waukegan Waterfront Center in Illinois

Case Study 4: Coordination Inside and Out – Harvard University North Campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts

08 Development Intensity

SOM’s view is that compact cities should be designed alongside a reasonable public transportation system, and successful high-density development design should primarily focus on its compactness and adjacency:

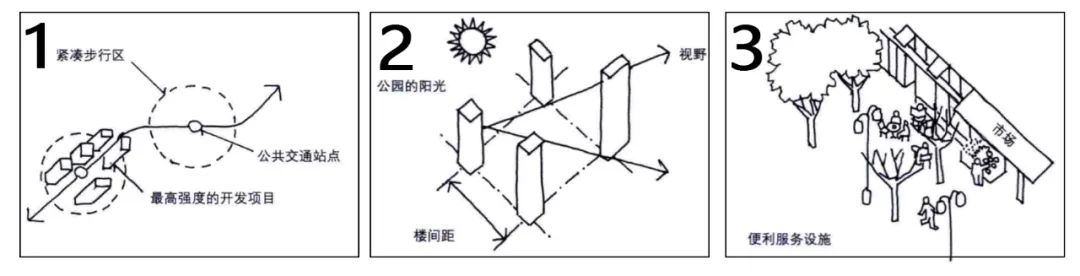

1 Compactness and Adjacency

1) Transit-Oriented Development: Transit-oriented development typically provides a dense living style that integrates public transportation with shopping, dining, and entertainment functions. It offers a comfortable and safe walking environment between public transport stations and residences, creating vibrant community life.

2) Development Planning: Propose reasonable solutions for increasing development intensity as much as possible. In North American cities with dense public transportation services, livable communities under construction adopt a development intensity of 300 residential units per 4000 m2. This is almost the limit; once the number exceeds 300, it becomes difficult to obtain open views, sunlight, and sufficient open space.

3) Public Facilities: A successful high-density living environment must provide comfortable conditions for residents, such as walkable distances to work, excellent views, proximity to supporting service facilities, cultural, recreational, and entertainment venues, and other exciting urban life elements.

Plan 1: Utilizing Brownfields, Saving Greenfields: Regional Reconstruction Urban Development Intensity – Chicago Central District Planning in Illinois

Plan 2: Accepting Development Intensity and Height – Bay Bridge Station Community Redevelopment Plan in San Francisco, California

09 Recognizability

Therefore, compared to threatening private interests, ideal urban construction must advocate the public interest dedicated to protecting and enhancing the uniqueness of urban resources. Creating/protecting a unique and memorable sense of place. SOM believes that urban recognizability can be increased from the following three aspects:

1 Recognizability Established by Natural Resources

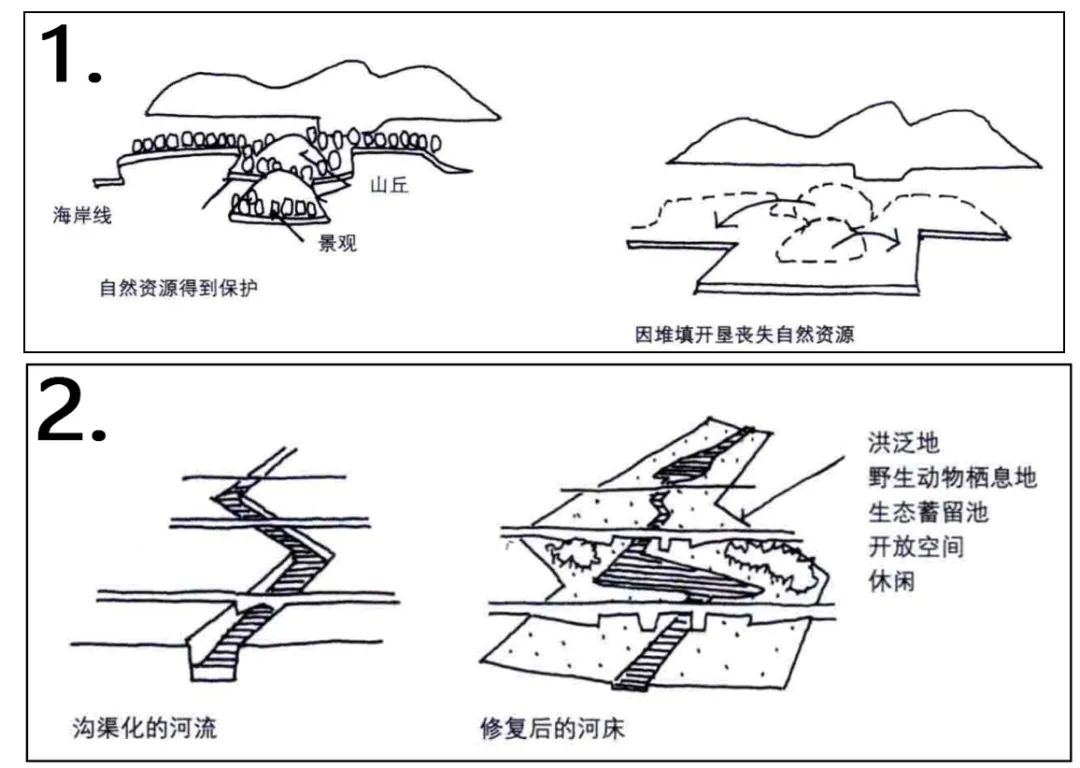

1) Protection: Rules must be established to prevent or specifically limit changes to existing natural resources. Typically, these rules apply to hilly terrain, waterfront boundaries, edge zones, forests, species habitats, and watershed corridors.

2) Restoration: Planning must be developed to restore or replace natural characteristics lost or damaged due to reckless urbanization.

3) Visual and Actual Accessibility: Rules must be established to maintain and restore visual and actual accessibility that can highlight natural resources. These rules will limit the scale of physical developments, remove projects that obstruct views and pathways of natural resources, and establish public rights of way for roads, trails, bike paths, and walking routes to facilitate access to natural resources.

2 Recognizability Established by Climate

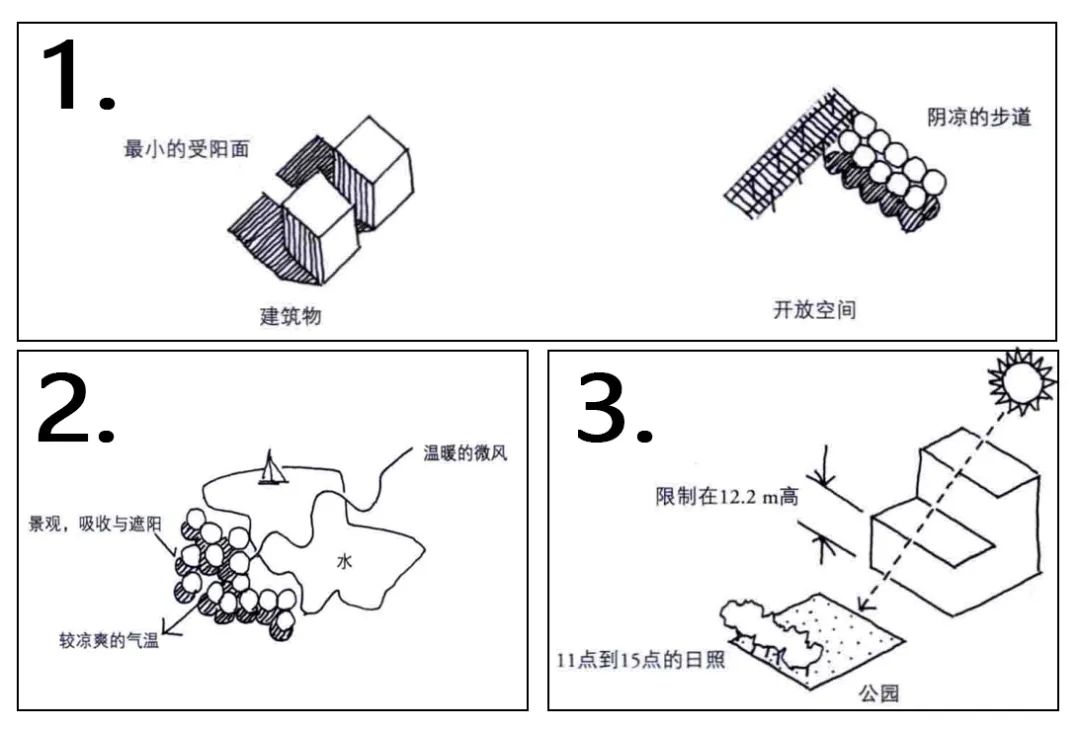

1) Sun Protection in Hot Climates: Besides insulation rules, indoor comfort in hot climates can also be enhanced by reducing the outdoor sun-facing area of each building. North-south window openings, special landscaping, and architectural designs can reduce sunlight exposure.

2) Utilization of Breezes and Water in Hot Climates: Through planning, open spaces and buildings can enjoy cooled afternoon breezes. This can be achieved by changing street orientations, using adjustable windows, and creating airflow channels.

3) Increasing Sunlight in Cold Climates: In cold climates, outdoor comfort can be achieved by increasing sunlight in locations such as parks and densely trafficked pedestrian areas.

4) Wind and Rain Protection in Cold Climates: To enhance outdoor comfort in cold climates, rain shelters and devices to block, reduce wind, and redirect airflow need to be installed.

3 Recognizability Established by Culture

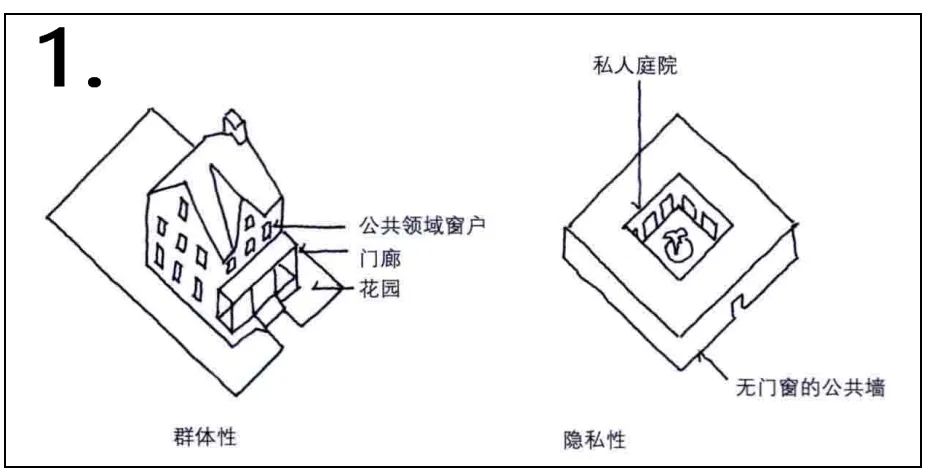

1) Recognizability Established by Contradictions of Privacy and Community: Cultural and historical tendencies towards privacy or openness are key aspects that establish recognizability.

2) Recognizability Established by Economic Resources: Economic resources largely determine a city’s self-awareness in architecture and design. Economically weaker cities often appear less complete, and areas with lower economic status are often accompanied by shorter buildings. Ironically, economically deprived areas can maintain their unique identity by adhering more strictly to traditional design concepts. Conversely, wealth often brings demands for modernization, uniformity, and demolition-reconstruction.

3) Recognizability Established by Urban History, Historical Sites, or Cultural Institutions: Urban builders need to define parts of the city that hold cultural significance to prevent them from being lost due to reckless implementation of new development projects.

4) Recognizability Established by Design: The recognizability of a city can be established through the construction of a building complex or even a single important building and open space that stands out in its environment, such as the Sears Tower and Hancock Building in Chicago, and the Burj Khalifa in Dubai; similarly, repeating building types of similar scale can also create a unified recognizability.

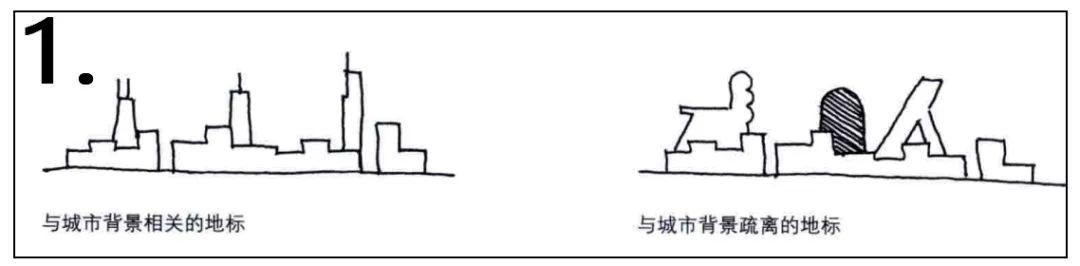

4 Recognizability Established by Landmarks

1) Aesthetic Appeal of Landmarks: Landmarks often have the strongest artificial visual impact in a city, but they also carry the risk of failing to integrate into the environment.

Case Study 4: Uncovering the Development Potential of Waterfront Areas – Huangpu River in Shanghai, China

Part Three

The Future of Cities

~Cities can establish a mechanism for rational and sustainable use of increasingly scarce resources, and at the end call for the establishment of a comprehensive design framework for population settlements and a nationwide planning process~

1.Need to Establish a Framework for Settlements

2.Revisiting Single-Purpose Design Education and Problem-Solving Approaches

Today, scholars discuss the power of interdisciplinary thinking, but in the “real world”, the focus of professional design remains confined to the “storerooms” of single disciplines. Professionals stubbornly strive for promotions within their respective fields, and barriers exist between disciplines, leading to our inability to understand the importance of urban design issues from the highest, broadest, and interconnected perspectives. Therefore, creating an educational system that communicates across various design disciplines is crucial.

3.Conclusion

Finally, personally, I hope the viewpoints in this book can provide some new insights and tools to encourage people (especially architects, landscape architects, and planners) to take a higher perspective and examine their disciplines in the context of urban construction.

Ultimately, sustainable and livable urban design does not stem from complex statistics, functional problem-solving solutions, or specific decision-making processes. Successful cities arise from advocating human values that are easy to understand and related to the sensory qualities of the environment, and transforming them into sustainable realities through design.

I hope that the examples I have chosen to illustrate these principles can provide a “working method” to show how cities can be designed, constructed, and rebuilt to create sustainable, humane human settlements, a gift for our future generations. Now, we deserve to strive for this.

END