Scan the code to follow Chip Dynamics and say goodbye to “chip” congestion!

Search WeChat

Search WeChat Chip Dynamics

Chip Dynamics

Dear C language warriors, have you ever faced the dilemma of choosing between regular functions, inline functions, and macros when you need to encapsulate a piece of code? Today, we will thoroughly resolve this issue!

Inline FunctionsAdvantages of Inline Functions

The most remarkable feature of inline functions is their ability to expand in place—the compiler directly “sticks” the function body at the call site, resembling the text replacement effect of macros like “copy and paste”.

For example, calling a regular function is like ordering takeout: you have to fill in the address (push the current environment onto the stack), wait for the delivery person (jump to the function address to execute), and after signing for it, you have to return the utensils (pop the stack to restore the scene). This back-and-forth “logistics cost” can be significant. In contrast, inline functions deliver the “takeout” (function body code) directly to your doorstep—the function body is embedded directly at the call site, eliminating the need for pushing to the stack, jumping, and popping the stack, thus speeding things up!

In simple terms, the “call” of an inline function is quoted—it does not go through the traditional “transport process” of functions but executes the code directly at the call site. This way, the most time-consuming operation of “stack frame allocation/recovery” during regular function calls is skipped, naturally improving program efficiency!

However, it is important to note that while inline functions are efficient, they are still “proper functions”: the compiler checks parameter types and avoids the “text replacement side effects” of macros (such as the issue of multiple evaluations of parameters), making them much safer than macros. Therefore, in C language, simple short functions are now recommended to be marked with inline, preserving the function’s specifications while enjoying execution efficiency close to that of macros, which is a perfect example of having both “fish and bear’s paw”!

Disadvantages of Inline Functions

However, in programming, there are no “both-and” scenarios. While inline functions can save the overhead of function calls by “expanding code in place”, they also come at the cost of “code bloat”—

Regular functions are like “shared bicycles”: the compiler generates only one copy of machine code, and all places calling it can “scan and use” it, storing only one copy in memory. But inline functions are more like “private cars”—every time they are called, the compiler has to “paste” their code in its entirety at the call site. As a result, the code size can balloon like an inflated balloon, leading to increased memory usage and potentially overwhelming the CPU’s instruction cache (equivalent to the CPU’s “temporary warehouse”).

Imagine this: if the entire program is likened to a book, regular functions are the “table of contents + chapters”, while inline functions are like “copying the content of each chapter directly onto every page that calls it”. The book becomes thicker, and flipping pages (cache lookup) naturally slows down—especially when inline functions are called excessively, the CPU cache may “not fit” so much duplicate code, leading to “cache misses” and ultimately slowing down overall efficiency.

Therefore, inline functions should be used “selectively”:

✅ Suitable for “short and concise” functions: for example, operations that can be completed in a few lines of code, such as calculating the sum of two numbers or checking for odd/even. They have a small code increment when expanded but can save the “running time” of function calls, making them highly cost-effective!

❌ Not suitable for “large functions”: if a function has hundreds of lines and is called everywhere, expanding it will double the code size, overwhelming memory and cache, making regular functions more cost-effective!

Function-like Macros

Function-like macros in C language are known as the “universal players” in parameter reception—they can “accept” parameters like regular functions but are not picky and do not “verify identity”!

For example, regular functions are like “custom restaurants”: whatever dish you order (what type of parameter you pass), the kitchen prepares the ingredients according to the menu (function declaration). For instance, if you want an “int version of max”, the kitchen makes a dish with “int ingredients”; if you want a “double version”, you have to order a dish with “double ingredients”—this is called “type checking”, which is safe but cumbersome.

In contrast, function-like macros are more like a “street food stall”: no matter what “ingredients” (parameters) you bring, whether int, char, or double, they all accept them and process them according to the same “cooking method” (macro definition). For example, this classic max macro:

#define max(a, b) ((a) > (b) ? (a) : (b))No matter if you pass int a=3, b=5, or char c=’x’, d=’a’, or even double x=3.14, y=2.71, it can directly apply the logic of “taking the larger of the two” and generate the corresponding code. This “non-type-checking” flexibility is like giving the code a “universal pass”—no need to write int_max, char_max, double_max for each data type… the code volume is halved!

However, behind the “universal” lies a hidden concern—just as street food stalls can be convenient, they can also “flip over”. Since macros do not check parameter types, if you accidentally pass a “strange type” (like an array or function pointer), or if there are “side effects” in the parameters (like max(i++, j++)), the compiler will not stop you and will execute the text replacement directly, which may leave you “dumbfounded”.

Therefore, this depends on the requirements:

✅ If you need quick operations that can “eat across types” (like simple numerical comparisons or bitwise operations), the “non-picky” nature of macros can help you save code and improve efficiency;

❌ If you pursue “type safety” or handle complex logic (like operations involving pointers or structures), it is better to stick with regular functions—after all, while “custom restaurants” may be cumbersome, the dishes they serve are more “reliable”!

As for improving efficiency, inline functions are a more reliable choice—they retain the type safety of functions while being able to “expand in place” like macros to save on call overhead. Unless macros can provide “irreplaceable convenience” (like certain low-level hardware operations), we should prioritize inline functions!

Differences Among the Three Musketeers

Next, I will provide a C language code example to further discuss the differences among regular functions, inline functions, and function-like macros:

int n_add(int a, int b){ return a+b;} __attribute__((always_inline)) inline int i_add(int a, int b){ return a+b;}#define d_add(a, b) ((a)+(b))int main(){ int a = 1, b = 2; int c = a+b; c = n_add(a, b); c = i_add(a, b); c = d_add(a, b); return 0;}The above C language code is quite simple; it calculates the sum of two int variables, but this calculation process uses four methods:

-

Directly using the + operator: c = a+b;

-

Writing a regular C function and calling it: c=n_add(a,b);

-

Writing an inline function and calling it: c=i_add(a,b);

-

Writing a function-like macro and calling it: c=d_add(a,b);

Just looking at the C language code does not reveal any differences; to understand the distinctions among these methods, we need to delve into the instruction level. Before compiling this C language code, let’s focus on examining the function-like macro definition.

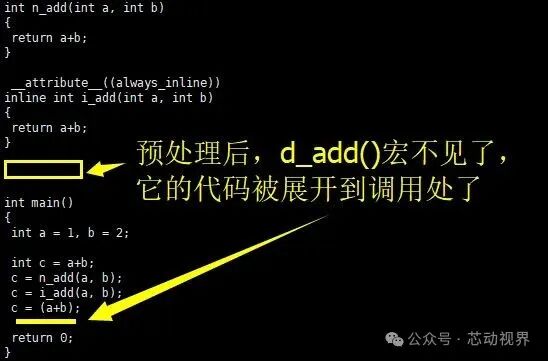

Readers should understand that the define macro in C language is processed during the preprocessing stage before compilation, so we can use the gcc -E command to view the preprocessed C language code:

As seen, during the preprocessing stage before compilation, the macro d_add() has disappeared, and its C language code has been replaced at the call site, which is one of the differences from functions—there is fundamentally no overhead of a call process. In fact, this characteristic of function-like macro definitions can accomplish tasks that regular functions and inline functions cannot do, as detailed in my previous article.

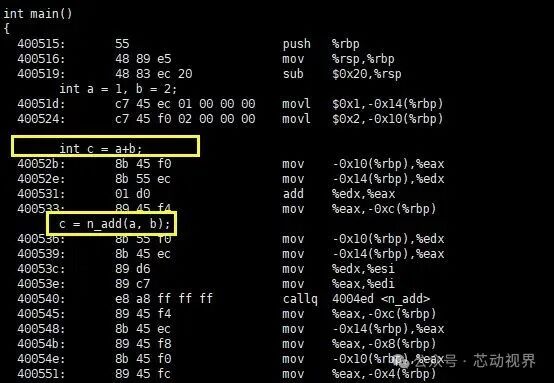

Now, let’s compile this C language code and view its assembly code:

Clearly, compared to directly using the ” + ” operator for calculation, the overhead of calling a regular function is greater and less efficient. Next, let’s examine the assembly code of the inline function:

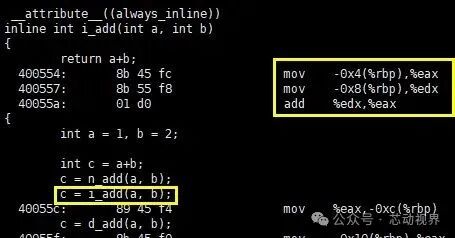

As seen, although the inline function is not expanded like a macro during the preprocessing stage, the compiler expands its instructions at the call site when generating instructions.

Readers can compare the assembly code of directly using the ” + ” operator and that of calling the inline function; they should find that the two are equivalent, meaning that the “call” of the inline function does not actually involve a call (callq) process, and its overhead is the same as that of macros and direct use of the ” + ” operator, both being lower than that of regular functions, thus achieving higher efficiency.

Conclusion

This article discusses the differences and applicable scenarios of regular functions, inline functions, and function-like macros in C language program development, along with specific code examples illustrating their roles in efficiency optimization. The study points out that although both inline functions and function-like macros can reduce function call overhead and improve execution efficiency to some extent, their characteristic differences are significant, and careful selection is required in practical applications.

From an implementation mechanism perspective, function-like macros achieve “pseudo-function” functionality through text replacement during the pre-compilation stage, avoiding the overhead of stack pushing/popping during function calls. However, they are fundamentally untyped text operations, which have obvious limitations: on one hand, they cannot perform parameter type checks, and passing unexpected types (like passing an integer to a macro expecting a pointer) may lead to undefined behavior; on the other hand, parameter expressions may cause unexpected calculations due to operator precedence issues (like MAX(a+1,b) may expand to (a+1>b) instead of (a+1)>b), requiring additional parentheses for safety. These defects make the reliability of function-like macros significantly lower than that of regular functions, and they should be used cautiously only in performance-sensitive and logically simple scenarios (like basic mathematical operations).

Inline functions, on the other hand, suggest embedding the function body directly at the call site through compiler directives (like the inline keyword), retaining the safety of type checking while avoiding the runtime overhead of function calls. However, inlining is not a “cost-free optimization”: if the function body is long or called infrequently, excessive inlining can lead to code bloat, increasing the probability of instruction cache (ICache) misses, which may reduce overall program performance. Therefore, the reasonable use of inline functions must meet two core conditions: first, the function logic should be simple (usually no more than 3-5 lines) and have a high execution time proportion; second, the calling scenario should be frequent (like within loops or high-frequency interfaces). For complex functions or infrequent calling scenarios, the independent code storage of regular functions and branch prediction optimization may be more advantageous.

In summary, in C language development, regular functions should be prioritized to ensure code maintainability and type safety; only when performance bottlenecks are clear and functions meet the characteristics of “short and concise” and “high-frequency calls” should they be considered for inline declaration; function-like macros, while capable of achieving extreme efficiency optimization, should have their usage scope strictly limited and only be used as a last resort when performance goals cannot be achieved through inline functions or other safe mechanisms.

If you find this article helpful, click “Share“, “Like“, or “View“!