In recent years, the astonishing drop in costs of photovoltaic (PV) and lithium batteries has sparked strong expectations in the climate policy and investment communities. Many hope that “Direct Air Capture” (DAC) technology can follow a similar trajectory of cost reduction. However, this analogy overlooks the fundamental differences in physical realities and market structures, necessitating a calm reassessment.

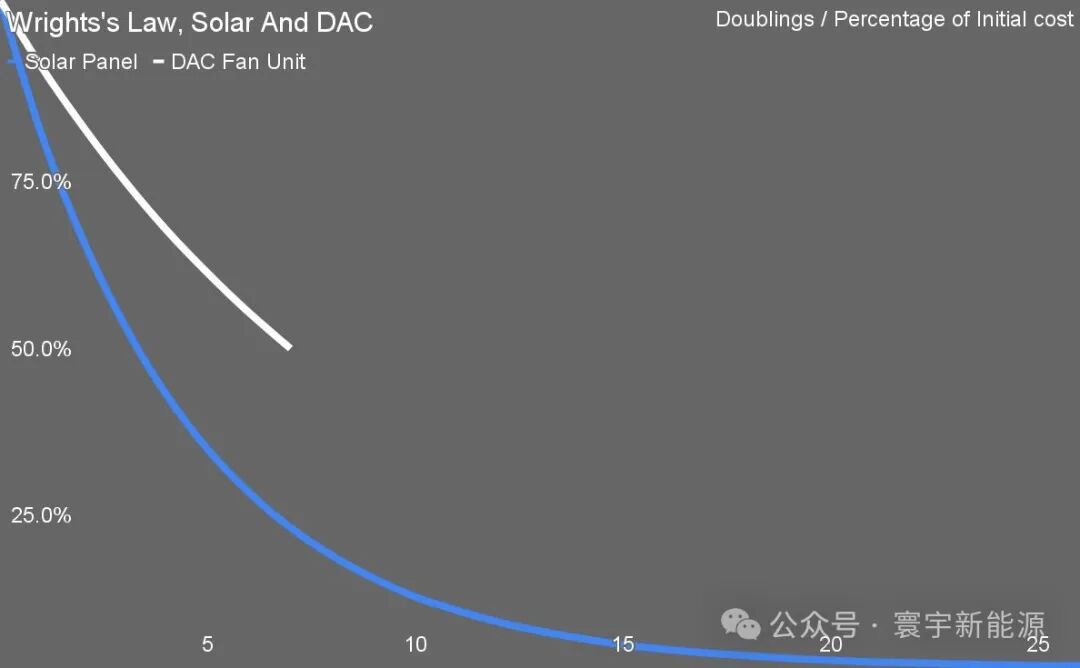

In the global effort to achieve the vision of “net-zero emissions”, Direct Air Capture (DAC) is seen as a beacon of hope for the “last mile” of carbon reduction strategies. Policymakers, investors, and industry advocates have compared it to clean energy star technologies such as solar PV and lithium-ion batteries, attempting to use “Wright’s Law” to predict the future cost reduction path of DAC— that is, as cumulative production doubles, unit costs decrease proportionally. However, this analogy is based on a misjudgment of technology, market, and physical laws, and optimistic expectations need to be corrected by a realistic perspective.

The author has studied DAC for fifteen years, having assessed the applicability of Global Thermostat in heavy rail transport, analyzed the real market of Carbon Engineering in enhanced oil recovery, and interviewed countless industry experts and entrepreneurs. Recently, I wrote a commentary on the operational difficulties of Climeworks— its annual capacity of 40,000 tons has only captured a total of 105 tons of carbon, and it has laid off 22% of its workforce—yet many in the comments still firmly believe that DAC can achieve a “qualitative cost reduction” like PV and batteries, prompting me to revisit this topic.

The success of PV and batteries relies on a clear and unified path. Guided by Wright’s Law, every doubling of global cumulative production leads to a 20% reduction in PV costs and a 19% reduction in battery costs. These significant, predictable learning effects benefit from their rapid entry into a vast market with billions of users: PV on rooftops, batteries in phones and then in electric vehicles, thus stimulating economies of scale, manufacturing standardization, and continuous innovation, driving prices down significantly in a short time.

Once PV manufacturing entered the gigawatt-scale factories, it achieved unprecedented leaps in efficiency. Automation, standardized production lines, improved material usage efficiency, and steadily increasing battery conversion efficiency have collectively driven costs down by over 99% since the 1970s. Batteries have also undergone a similar process: from initially expensive consumer electronics components to a scale explosion brought about by the rise of electric vehicles in the 2010s. Continuous optimization of battery chemistry, production processes, and supply chain management has led to a price drop of over 90% since 2010. The key is that both have ultimately become truly commoditized products, economically attractive even without subsidies.

In contrast, DAC faces fundamental obstacles in replicating the cost reduction paths of PV or batteries—structural complexity, physical limitations, and a narrow market.——DAC

While DAC systems are also modular engineering designs, their scale and replicability are entirely different from PV and batteries. The latter two have units that are micro, standardized, and suitable for mass production, numbering in the billions, facilitating parallel manufacturing and iterative optimization. In contrast, DAC’s modular devices, such as those envisioned by Climeworks, are industrial-grade systems that process millions of cubic meters of air, requiring a vast amount of air to capture one ton of carbon dioxide. Even with extreme modularization, each device remains a capital-intensive heavy industrial facility, requiring thousands or even tens of thousands of devices to achieve a globally effective scale, far below the replication multiples achievable by PV or batteries, making it difficult to generate sufficient learning effects.

Moreover, DAC heavily relies on highly mature industrial components, such as large fans, adsorbent materials, heat exchangers, compressors, and pumps. These components have been widely used in other industries, with manufacturing costs close to optimal ranges, and there are no significant “unexploited” technological dividends to be harvested. Optimizing adsorbents and improving thermal management efficiency may yield marginal improvements, but fundamentally revolutionary cost reduction paths are extremely limited.

The greatest obstacle to DAC replicating the PV route stems from immutable physical facts:extracting CO₂ from the thin atmosphere is essentially a highly energy-intensive process. Unlike the primary costs of PV batteries, which come from manufacturing and materials, DAC faces thermodynamic limits. Even in the most optimistic scenarios, DAC requires hundreds to thousands of kilowatt-hours of energy to capture a unit of carbon, a cost that cannot be erased through process improvements—this is a bottom line dictated by the laws of physics.

Additionally, the construction of DAC is extremely “heavy”: to capture a million tons of carbon dioxide annually, a large amount of steel, concrete, adsorbent materials, and high-end industrial equipment is required. DAC devices cannot achieve the miniaturization seen in chips, nor can they significantly reduce material usage, while the increase in material demand may conversely drive up costs. In stark contrast, a major driver of cost reduction in PV and batteries is the continuous reduction in material consumption per unit.

Market structure also poses a critical barrier. PV and batteries are essentially consumer-facing products that can self-promote based on their economics even without subsidies, rapidly expanding their market. In contrast, DAC is not a commodity but an environmental service—its value entirely depends on policy support, such as carbon pricing, financial subsidies, or emission regulations. The lack of stable, sustained market demand means its production growth is far less than the former two, and the multiplier effect of the learning curve is difficult to achieve. The policy market is also easily influenced by political changes, budget cuts, and public opinion, leading to uncertainty in DAC expansion.

Historically, the appropriate comparison for DAC should be with nuclear energy, large chemical plants, or carbon capture facilities in coal-fired power plants, rather than PV or batteries. These technologies also face challenges of complex engineering, limited scale, and fragile markets, often failing to achieve large-scale cost reductions, and even seeing costs rise with expansion. The reality is that, even in the most optimistic estimates, DAC will see unit costs decrease by only about 10% for every doubling of cumulative production. For example, the only component in DAC that might see large-scale replication is the fan module; even if Climeworks or Carbon Engineering were to increase fan production to 8,000 units, they would need to build a capture device wall of up to 64 kilometers. To further reduce costs by 10%, they would need 128 kilometers and 16,000 units; to reduce costs again by 10%, it would require 256 kilometers and 32,000 units, with difficulty increasing exponentially.

In contrast, a 1GW solar power station has about 1.8 million solar panels. The scale of replication and potential for cost reduction between the two are worlds apart.

From a more neutral analysis by authoritative institutions, such as the International Energy Agency, Harvard Belfer Center, and the National Academy of Sciences, it is generally believed that even with large-scale deployment in the coming decades, DAC will still have a unit carbon capture cost of over hundred dollars per ton. The most aggressive predictions only reduce costs to 150-250 dollars/ton; more realistic estimates are even higher. As for the industry’s proposed target of “below a hundred dollars”, it is severely detached from reality, as if challenging the laws of physics, relying solely on unrealistic energy costs and technological leaps.

Therefore, policymakers and investors should adopt a more cautious attitude towards DAC. Before global clean energy is fully adopted and the power system decarbonized, limited resources should be prioritized for electrification, renewable energy, and energy-saving technologies, which are proven paths with lower unit reduction costs.

Current investments in DAC should be limited to the R&D phase, focusing on improving efficiency, reducing energy consumption, and clarifying its true potential. In commercial deployment and infrastructure construction, premature investment may solidify high-cost paths, missing the development space for better alternative technologies.

In the foreseeable decades, carbon removal strategies should focus on natural solutions and soil carbon sequestration, which are low-energy and more scalable methods. Hoping to achieve the 2050 target by vacuuming enough carbon dioxide is less practical than promoting structural emission reduction transformations.