Crazy Computers

The microcomputer—or personal computer—may be one of the most revolutionary inventions of the 20th century. Throughout history, no technology has been able to so rapidly and continuously overturn itself and iterate in such a short time.

In 1946, the world’s first general-purpose computer, ENIAC, was born at the University of Pennsylvania; in 1947, a young PhD at Bell Labs in the United States created the transistor with alchemist-like skill, allowing the new generation of computers (TRADIC) born in 1954 to shrink from the size of a presidential suite to a modular cabinet, making transistors the best-selling industrial product; in 1958, before Texas Instruments could even profit from transistors, one of its engineers produced a card that would disrupt their own business—the integrated circuit; in 1968, an Italian immigrant living in the United States invented the microprocessor; that same year, another inventor of the integrated circuit began Intel’s meteoric rise. By this time, computers had shrunk to the size of a few workbenches, and Moore’s Law accurately pointed out that every 18 months, the performance of microprocessors would double while prices would drop by 50%. Americans were eager to take their inventions out of the lab, and computer technology began to spark various technological revolutions across industrial sectors. The computer typesetting technology we mentioned in the first issue is just a drop in the ocean of this wave. The efficiency gains brought by computers are evident, propelling the economic acceleration of commercial society like a divine hand.

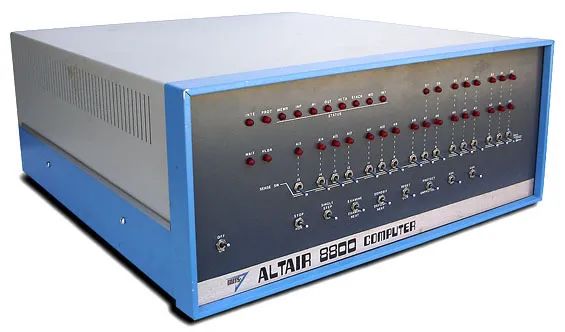

However, before people could fully explore the industrial applications of large computers, in 1974, an electrical engineer, scarred by the Vietnam War, assembled a microcomputer the size of a suitcase based on Intel’s latest 8080 microprocessor—the Altair 8800—marking the moment when computers could belong to individuals. This astonishing news spread around the world almost overnight with the publication of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics, stirring waves of future aspirations in countless hearts, including four young talents who would soon change the world under the names of “Microsoft” and “Apple.” From then on, computing technology spiraled out of control, reaching into every corner of commercial civilization, becoming the lifeblood of the world in just a few decades.

The world’s first personal computer

Altair 8800

After World War II, all significant leaps in computer technology occurred across the ocean in the United States. Like other countries unwilling to fall behind, China struggled to catch up under the shadow of the Cold War. In addition to a lack of material resources, China faced technological blockades and material embargoes from the Western camp, and the deterioration of Sino-Soviet relations left the first generation of non-professional researchers in China as isolated development teams. The tumultuous events of the first thirty years of the Republic made information increasingly closed off.

However, in fact, China’s pace of catching up was not slow. In 1956, under the leadership of Premier Zhou Enlai, computing technology was included as an urgent measure in the “Twelve-Year Scientific Development Plan.” The Chinese Academy of Sciences established four research institutes in Zhongguancun (Institute of Computing, Institute of Electronics, Institute of Automation, Institute of Semiconductors) to accelerate the development of China’s computer industry. Fueled by a fervent desire to “bring glory to the country,” they climbed the technological tree. In 1958, they built China’s first small computer (Model 103) based on Soviet blueprints; by 1960, China had already mastered the ability to design and manufacture its own computers (Model 107); in 1965, China produced its second-generation general-purpose mainframe (Model 109) using domestically developed transistors; by 1970, China’s first computer using integrated circuits (Model 111) was born at the Institute of Computing. Although starting 12 years later, the Chinese caught up with the world in just 12 years, even surpassing the rapidly rising neighbor Japan at one point. Moreover, that year, the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Chinese character information research group had already begun researching the display and input of Chinese characters on the Model 111. Scientists wielded the hammer of computing technology, striving to break through the door to the digital age for the future of their country. While the Chinese worked hard to integrate computers with Chinese character civilization, Americans had already begun to let computers and commercial civilization join forces. However, in 1975, the commercial success of the Altair 8800 did not attract much attention from Chinese scientists. In the completely insulated planned economy of China, the vast majority of people were unaware of the technological prospects beyond commercial value; entangled in military objectives and construction missions, many researchers developed a “solid-state” faith in large machines, drifting further away on a branch of the technological tree that was heavy with responsibility. Meanwhile, Japan, which had once lagged behind China, had quietly begun assembling new models from IBM and Radio Shack on its production lines. Would China fall behind again?

China’s self-developed

integrated circuit mainframe (Model 111) born in 1970

later used for Chinese character information processing experiments

Unwilling to Fall Behind

Not paying much attention does not mean that the Chinese were unaware of the birth of microcomputers. In fact, someone in China quickly recognized the promotional potential of microcomputers. Thus, in the autumn of 1974, after some twists and turns, the microcomputer research plan was taken over by the Sixth Research Institute of the Ministry of Machinery Industry. The establishment of the “Sixth Institute” was based on civilian purposes, officially named the “Institute of Electronic Technology Promotion and Application Research”—which sounded quite appropriate for microcomputer research, but in reality, the Sixth Institute had no foundation for developing computers. The microcomputer research team was entirely composed of novices; they did not share the commercial ideal of “having a computer on every desk” like their American counterparts, but in China, the belief in “overcoming difficulties and bringing glory to the country” was enough to motivate everyone to invest their full efforts.

No one had seen what the Altair 8800 really looked like; at the beginning, the only materials they had were a 1975 magazine issue that featured the “Altair” and gradually some scattered information that was published later. This was completely different from the Soviet Union, which had direct access to blueprints; all logic had to be deduced independently. Under such circumstances, 28 months later, on April 23, 1977, China’s first microcomputer, the “DJS-050,” miraculously came into being. All components were concentrated on a single circuit board, hence it was also called the “Functional Control Single Board Series.” It had no keyboard, no mouse, and a black-and-white television served as the display. Except for the central microprocessor, which was implemented with three chips to achieve the functionality that Intel had on one chip, the performance of this computer was already comparable to the popular 8-bit machines worldwide. China had once again avoided “falling behind” in just three years, with a “new recruits” team and scant technical materials. However, that was the end of the story…

This DJS-050, which pioneered the history of Chinese microcomputers, did not receive the promotion it deserved like its counterparts across the ocean; it was never mass-produced and remained merely a prototype. After receiving honors at the National Science Conference in March 1978, it seemed to have completed its mission of “bringing glory to the country.” This was largely due to the bizarre situation caused by the severe disconnection between research and industry at that time, but in that era, no one felt anything unnatural about it, as “production” did not fall within the responsibilities of research units. The task of scientists was to continue “bringing glory to the country.” After the “050,” there were “051,” “052,” and “054,” with keyboards, mice, and advanced imported components gradually added, and domestic microcomputers began to take shape. However, they were all, without exception, just one prototype after another.

China’s self-developed

first microcomputer – DJS 050

Understanding the Future

China did not fall behind; however, the Chinese people were far behind. In research institutions, scientific competitions were in full swing, and China had acquired new technologies that developed countries possessed. Yet, among the general public in China, almost no one knew what a computer was; those who did might tell you it was an American gimmick, far less useful than China’s abacus. Meanwhile, in the United States, the TRS-80, APPLE II, and Commodore had already made it to the cover of Byte magazine as the “Three Musketeers of Microcomputers” in 1977; the eight major manufacturers, dubbed “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” were continuously delivering various forms of microcomputers to offices across industries, with the “Snow White”—IBM—brewing the true future of personal computers—PC—Personal Computer.

Various early microcomputers:

The 1977 “Three Musketeers of Microcomputers”

(from left: Commodore PET 2001-8

Apple II, TRS-80)

In the summer of 1981, when IBM’s PC was born, for most Chinese industry insiders, it was merely a transformation of the “colorful” microcomputer world into a “six-color” one. In 1982, a single-board computer research team from the Sixth Institute was sent to Japan to continue developing the next generation of uncertain single-board computers. However, an event that winter changed this stagnant situation. A deputy chief engineer of the Sixth Institute was promoted to deputy director, and this person, now in a position of power, aimed to push the Sixth Institute’s work nationwide. His name was Yu Zhengsheng.

That same winter, IBM released the technical documentation for the PC, and manufacturers around the world began to adopt it, marking the beginning of the era of compatible machines. Although this commotion had not yet reached China, Yu Zhengsheng sensed an irreversible trend in IBM’s actions. Thus, he convened a meeting in November. The three technicians who had gone to Japan were also called back, and they hurriedly attended this meeting. By this time, the Ministry of Machinery had been renamed the Ministry of Electronics, and the leadership of the Sixth Institute had changed, signaling the possibility of greater changes ahead. Indeed, Yu’s first major order was to halt their current work. At this meeting, they learned for the first time what an “open” personal computer was and what a “compatible machine” meant. Years later, they still clearly remembered Yu’s words that day: “Before this, the world’s microcomputers were diverse. After this, the world will make the same microcomputer.”

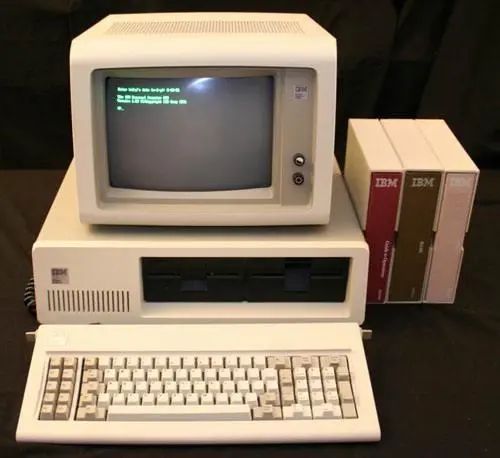

IBM·PC launched in 1981

In the following years

the form of personal computers “unified”

A key figure making a crucial decision at a critical moment undoubtedly saved the Chinese microcomputer industry from many detours. After a national computer coordination meeting in early 1983, the project to develop PC-compatible machines was officially launched. The project team formulated a plan, and researchers split into two groups: one was the original single-board computer team, led by Qian Lejun, who immediately returned to Japan to shift their research direction to “PC-compatible machines”; the other was led by a young engineer named Yan Yuanchao, who was tasked with developing a Chinese operating system for compatible machines. (For the story of Yan Yuanchao’s development of the Chinese operating system, please refer to the second issue of this series, “CCDos.”) This project, aligned with the global trend in computer development, was destined from the start to be more than just about “bringing glory to the country”; it aimed to take China’s microcomputers out of the lab, into applications, and into the hands of the public.

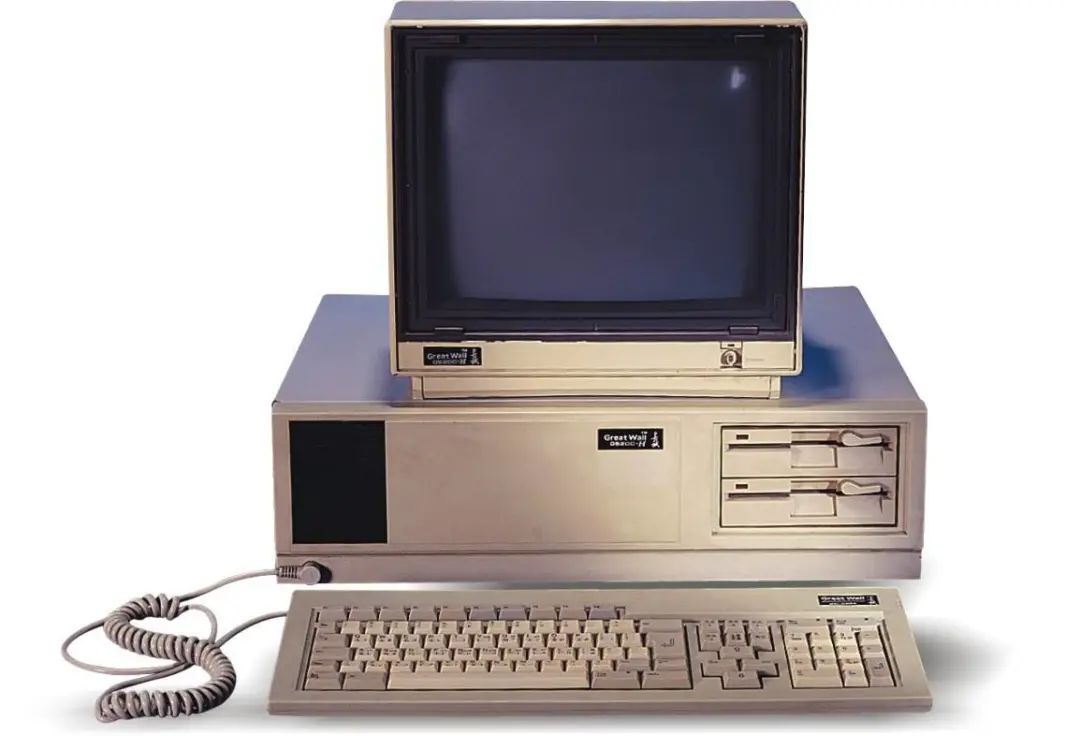

With both teams working diligently, in August 1983, China’s first PC-compatible machine was exhibited at the Beijing Exhibition Hall; in October, Yan Yuanchao was ordered to take this machine to Geneva for the “International Telecommunications Exhibition.” This was the first time a microcomputer made in China appeared on the international stage. This machine, fully compatible with the IBM PC and capable of displaying, inputting, and printing Chinese characters purely through software solutions, truly astonished many foreign friends. The Sixth Institute decided to name its achievement after Beijing’s symbol, the “Great Wall,” and soon after, China’s first PC-compatible machine was officially named “Great Wall 0520.”

China’s first personal computer with

commercial value

Great Wall 0520CH

Towards Industrialization

In 1984, Deng Xiaoping spent his Spring Festival in Shanghai. When the chief designer attended the “Ten-Year Science and Technology Achievements Exhibition,” he expressed the sentiment that “the popularization of computers must start with children.” This became the most powerful promotion of microcomputers in China at the time, widely disseminated by newspapers and media, sparking a lasting computer craze among middle and primary school students in Shanghai, which gradually spread nationwide, planting the seeds for the civilian microcomputer market. Although the prices of microcomputers at that time were vastly different from the income levels of Chinese people, their path to popularization among the public still needed to be nurtured alongside social progress. However, at the beginning of that year, Zhongnanhai became the first major unit wanting to bring microcomputers into its office, and thus held a computer selection meeting, where the “Great Wall 0520” was successfully selected, allowing domestic computers to enter the office market.

In April, Yan Yuanchao was once again summoned to the Computer Bureau, where Yu Zhengsheng requested him to begin implementing the second phase of the Chinese character disk operating system CCDOS. Yan proposed a two-step plan at the beginning of CCDOS development: the first step was to achieve it purely through software, and the second step was to design a new display card as needed to enhance the capability and speed of Chinese character processing. Now, as the Great Wall 0520 was about to face its first user, it had to be in the best condition to “go to work.” However, at this time, Yan was developing CCDOS 2.0, which made the entire project team tense. In June, Yan moved the CCDOS 2.0 development team to a guesthouse in Beijing’s Madian to continue their work. In August, he followed a small team to Hong Kong to develop the next generation of Great Wall microcomputers.

Yan proposed two plans for the new hardware design: one was graphical, directly transmitting Chinese character graphics to the display card for display on the screen; the other was a character-plus-graphics method, which required a character generator in the display card, allowing the central processor to transmit only the character codes to the display card, which would generate the Chinese character graphics, greatly improving display efficiency, but correspondingly increasing the difficulty of development. Six months passed quickly, and in February 1985, when the small team returned to Beijing after completing the first plan, Yu Zhengsheng had already been reassigned from the Computer Bureau. The new leader, Wang Zhi, frowned after watching the small team’s demonstration of their results. Although the technical goal of displaying 25 lines of Chinese characters had been achieved, the display speed was too slow, with characters scrolling down the screen line by line, severely affecting reading efficiency. When Yan proposed that there was another plan, Wang immediately “sent” Yan back to Hong Kong. In mid-May, Yan returned to Beijing with the new display card, and by this time, the Chinese character display speed of the Great Wall microcomputer had become comparable to that of English.

That year, the Great Wall 0520 was successfully mass-produced and attracted a lot of attention at various exhibitions. At the COMDEX exhibition in the United States, its 640×480 resolution and ability to display 25 lines of Chinese characters caught the attention of many, especially the Japanese—who were busy sketching the circuit diagram of the Great Wall 0520, trying to figure out how the Chinese achieved it.

China finally had its first truly commercially valuable microcomputer. In its initial years, the Great Wall 0520 dominated the market with its superior Chinese character processing capabilities, even leading to the IBM 550 model, specifically launched for the Chinese market, failing to sell domestically. In December 1986, the Ministry of Electronics established the Great Wall Company, and Wang Zhi resigned from his official position to become the general manager of the new company, fully committed to the industrialization of China’s microcomputer industry. He not only successfully established China’s first microcomputer production line but also pioneered the OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) production model in China. By 1987, 15 manufacturers across the country were simultaneously producing the Great Wall 0520, thus leading “Great Wall” to be the first to enter the era of industrialization in domestic microcomputers.

Wang Zhi – Chairman of China Great Wall Computer Group

Pioneer of China’s personal computer industrialization

Son of General Wang Zhen

China has its own personal computer industry, a moment worth remembering. However, at that time, China’s new technologies had just stepped into the door of a market economy, and a commercial environment benefiting the public had yet to form, making the ideal of popularizing personal computers to every household seem distant. In the future, China’s emerging technology enterprises would have to undergo unprecedented trials in the market to achieve the revitalization of the national industry.

References (Upper and Lower Parts)

Ling Zhijun, “China’s New Revolution”

Website of the Institute of Computing, Chinese Academy of Sciences: History of Computer Development

Liu Ren, Zhang Yongjie: “CCDos Yan Yuanchao”

Yan Yuanchao: “CCDos and Great Wall Microcomputers”

Wikipedia entries: Altair 8800, TRS-80, IBM PC

Ling Zhijun, “Lenovo’s Wind and Cloud”

Written by | Zhang Qingsheng Zhang Jisu Host|Zhang Jisu

Edited by | Liu Zhen Reviewed by | Zhang Yi