Scan the code to follow Chip Dynamics and say goodbye to “chip” congestion!

Search WeChat

Search WeChat Chip Dynamics

Chip Dynamics

Dear C language enthusiasts, have you ever been confused?

Your teacher says, “Pointers are the soul of C language,” but when you stare at the line of code int* p = &a;, it feels like reading a foreign language—what is &? What does * do? What exactly does the pointer variable p store?

Today, we will use relatable life scenarios to thoroughly explain the “difficult brothers” of addresses and pointers!

Memory Address: The “Super Rental Apartment” for Programs

To understand addresses and pointers, we first need to clarify how programs “live” in a computer.

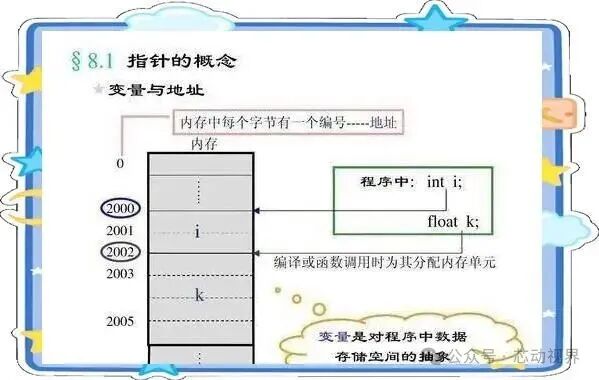

Imagine your computer’s memory as a super-large rental building, with countless small rooms (memory units) on each floor. Each time a program runs, the system allocates a batch of rooms to store variables, functions, data, etc.

For example, when you write int age = 25; in your code, the compiler will find a small room in memory, put the number 25 inside, and then label this room with a “door number” (for example, 0x7ffe5a3c7a9c). This door number is what we refer to as the memory address.

1.1 Each Variable Has Its Own “Room Number”

Using the C language’s & operator (read as “address-of operator”), you can directly obtain the door number of a variable.

For example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int age = 25; // Print the address of age (note: %p is the format specifier for printing addresses)

printf("The address of age is: %p", &age);

return 0;

}Running this code will give you an output similar to 0x7ffe5a3c7a9c. This is the “door number” of the age variable in memory.

1.2 The Essence of Addresses: Binary Numbering

A memory address is essentially a string of binary numbers, which is easier to read when converted to hexadecimal (like the above 0x prefix). Just like your apartment’s door number is “Building 1, Unit 2, Room 303,” a memory address is a unique identifier assigned by the system to each memory unit, ensuring that data does not get “delivered to the wrong door”.

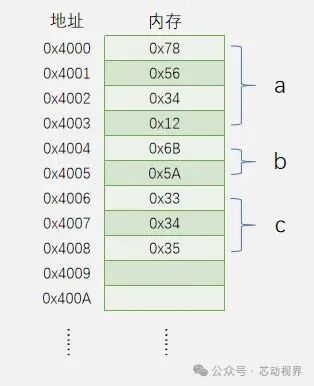

We define the following variables a, b, c:

int a = 0x12345678;

short b = 0x5A6B;

char c[] = {0x33, 0x34, 0x35};The distribution of variables a, b, and c in memory addresses is as follows:

Pointer: The “Delivery Guy” for Addresses

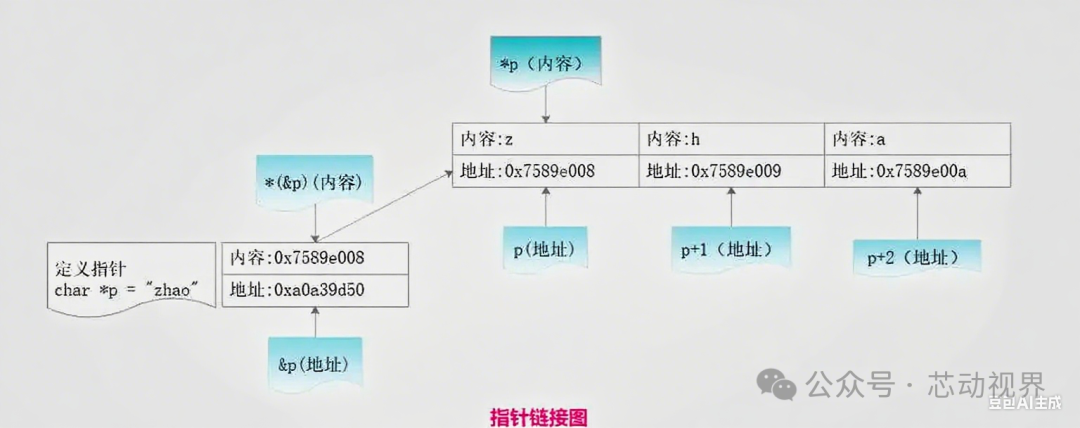

Now the question arises: how does the program “find” the location of a variable? This is where pointers come into play.

A pointer variable is essentially a “notebook that stores addresses.” Its uniqueness lies in the fact that it stores not ordinary data (like numbers or characters), but the memory address of another variable.

2.1 How to Create a Pointer Variable?

When declaring a pointer variable, you need to add * before the variable name to indicate that it is a pointer; you also need to specify what type of variable’s address it can store (this is very important! We will emphasize this later).

For example, to store the address of an int type variable, the pointer variable should be declared as int*:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 10;

int* p = &a; // Get the address of a and store it in pointer variable p

return 0;

}// p is a variable (pointer variable), a space, p on the left is written as int* // * indicates that p is a pointer variable, // int indicates that p points to an integer (int) type objectHere, it is important to note: * is a “pointer type modifier” when declaring, and is a “dereference operator” when used.

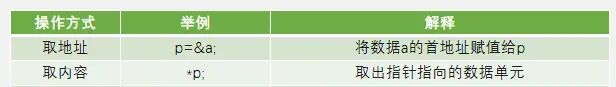

2.2 Dereferencing a Pointer: Finding Residents by Door Number

With pointer p, how do we find the value of age through it? This is where the * operator (dereference) is needed:

printf("The age value found through p: %d", *p); // Outputs 25 (equivalent to finding the resident at door number 0x7ffe5a3c7a9c and getting the number inside)To summarize:

-

&: Address-of operator, equivalent to “checking the resident’s door number”;

-

*: Dereference operator, equivalent to “finding the resident by door number”;

-

Pointer variable p: stores the address (door number), but through *p, you can manipulate the data inside that address (the resident).

Pointer’s “Type Compulsion”

Pointer’s “Type Compulsion”

Why must the data type being pointed to be specified?

You may have noticed that pointer variables must be declared with a type (like int*, char*). Is this a “compulsion” of the C language? Of course not! It is directly related to the “working capability” of pointers.

3.1 Different Types of Pointers Have Different “Step Sizes”

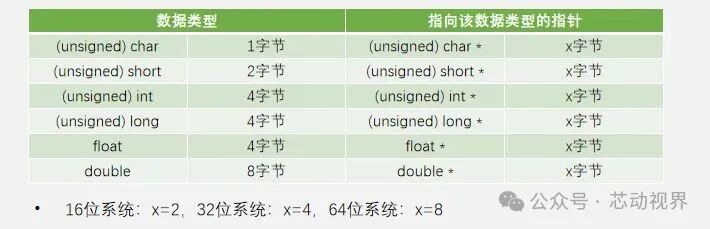

Assuming the variables in memory are arranged in small rooms, the size of each room is determined by the data type:

-

char type occupies 1 byte (single room);

-

int type usually occupies 4 bytes (double room);

-

double type occupies 8 bytes (large flat).

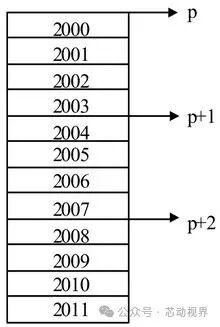

The type of pointer determines how many bytes it “steps over”. For example:

-

char* pointer steps 1 byte (suitable for finding single rooms);

-

int* pointer steps 4 bytes (suitable for finding double rooms);

Let’s verify this with an example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 0x12345678; // Hexadecimal number for easy memory layout viewing

char* c_p = (char*)&a; // Force convert to char* pointer (to be discussed later)

int* i_p = &a; // Print the next address of int* pointer (step size 4 bytes)

printf("Next address of int*: %p", i_p + 1); // Outputs 0x7ffe5a3c7a9c + 4 = 0x7ffe5a3c7aa0

// Print the next address of char* pointer (step size 1 byte)

printf("Next address of char*: %p", c_p + 1); // Outputs 0x7ffe5a3c7a9c + 1 = 0x7ffe5a3c7a9d

return 0;

}The output will validate our conclusion: int* pointer moves 4 bytes each time, while char* moves 1 byte each time. This is the significance of pointer types—telling the compiler “this pointer will operate on data of this size,” preventing out-of-bounds access.

3.2 Pointer Type Mismatch?

If you forcibly access data with a pointer of the wrong type, what will happen? For example, using a char* pointer to read an int variable’s value:

int a = 0x12345678;

char* c_p = &a; // Warning: type incompatible (but many compilers won't throw an error, just a warning!)

printf("%x", *c_p); // May output 0x78 (only read the last byte)In this case, you will only get the last byte of the int variable, just like tearing open a package and only seeing a small corner, revealing only part of the content. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that the pointer type matches the data type it points to (unless you intentionally want to manipulate the underlying bytes, in which case explicit type conversion is needed).

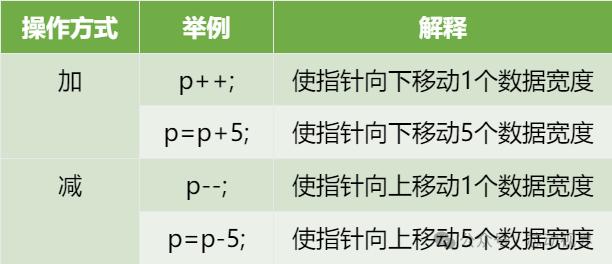

Pointer Arithmetic

Pointer arithmetic: it is not simple numerical addition or subtraction. As mentioned earlier, pointer addition and subtraction are related to the type. For example, for int* p, p + 1 actually means p + sizeof(int) bytes. So what about p + 2? It would be p + 2 * sizeof(int).

Guide to Avoiding PitfallsPitfall 1: Wild Pointers (Uninitialized Pointers)

Error Scenario: Using a pointer directly after declaration without initialization.

int* p; // Dangerous! p is a wild pointer (unknown which memory address it points to)

printf("%d", *p); // Crash! May access protected system memoryThe reason: the pointer variable p is not automatically initialized to NULL upon declaration; its value is a “garbage value” in memory (possibly an address used by a previous program). Dereferencing it is like “delivering a package to a random door number,” which may not find a resident and could even trigger a system crash.

Solution: Immediately initialize the pointer to NULL (null pointer) after declaration, and check if it is NULL before use.

int* p = NULL; // Initialize to null pointer (equivalent to "no address yet")

if (p != NULL) { // Check before use

printf("%d", *p);

} else {

printf("Pointer does not point to valid memory!");

}Pitfall 2: Using the Wrong Type of Pointer

Error Scenario: Using a char* pointer to operate on an int variable.

int a = 0x12345678;

char* c_p = &a; // Type mismatch (warning)

printf("%x", *c_p); // May output 0x78 (only read the last byte)The reason: the pointer type determines how memory is interpreted. A char* will treat 4 bytes of memory as 1 byte character, leading to data loss.

Solution: Ensure that the pointer type matches the data type it points to. If cross-type access is necessary (like manipulating binary data), explicit type conversion is required:

char* c_p = (char*)&a; // Explicitly convert to char*, clearly telling the compiler "I want to process by bytes"Pitfall 3: Returning the Address of a Local Variable

Error Scenario: A function returns a pointer to a local variable.

int* getAge() {

int age = 25; // Local variable, stored in stack memory

return &age; // Return the address of a local variable (dangerous!)

}

int main() {

int* p = getAge(); // p points to already freed memory

printf("%d", *p); // Crash! or output random value

return 0;

}The reason: local variables are stored in the function’s stack memory, which is reclaimed after the function execution ends. At this point, the returned pointer becomes a “wild pointer,” pointing to invalid memory.

Solution: If you need to return dynamically allocated memory, use malloc to allocate on the heap (remember to use free to release it):

int* getAge() {

int* p = (int*)malloc(sizeof(int)); // Heap memory, will not be reclaimed after function ends

*p = 25;

return p;

}

int main() {

int* p = getAge();

printf("%d", *p); // Outputs 25

free(p); // Remember to free after use! Otherwise, memory leak

return 0;

}Pitfall 4: The “Increment/Decrement” Trap of Pointers

Error Scenario: Confusing the difference between p++ and (*p)++.

int arr[3] = {10, 20, 30};

int* p = arr;

p++; // p points to arr[1] (address +4)

printf("%d", *p); // Outputs 20

(*p)++; // Increment after dereferencing, arr[1]'s value becomes 21

printf("%d", *p); // Outputs 21

printf("%d", arr[1]); // Outputs 21 (original array modified)The reason: p++ moves the pointer to the next element (address changes); (*p)++ modifies the value of the element pointed to by the pointer (data changes). Beginners often confuse the two, leading to logical errors.

Solution: Clarify operator precedence—() has higher precedence than ++, so (*p)++ dereferences *p before incrementing; while p++ increments the pointer itself.

Conclusion

After learning today’s content, you should understand:

-

Addresses are the “door numbers” of each variable in memory, obtained using &;

-

Pointers are “notebooks that store addresses,” and using * to dereference allows you to manipulate the corresponding memory data;

-

The type of pointer determines how it “reads and writes memory” (step size, data parsing method);

-

The key to safely using pointers: initialization, type matching, boundary checking, and avoiding wild pointers.

Pointers may seem complex, but essentially they are C language’s “remote control for memory”—they allow you to directly manipulate memory, writing more efficient code (for example, using pointers to avoid copying large objects when passing parameters to functions), but they can also “blow up your own house” due to improper operations (like wild pointers causing crashes).

If you find this article helpful, click “Share“, “Like“, or “Looking“!