This issue, the editor shares an article from the EUROCRYPT 2024 conference chapter on Advanced Public-Key Encryption, authored by researchers from Eindhoven University of Technology. This article abstracts the ElGamal encryption algorithm as a primitive called RRR relations (random self-reducible relations) and concludes that it cannot be proven to be OW-CCA-1 secure in the standard model, proposing a technique based on meta-reduction to prove this conclusion.

New Limits of Provable Security and Applications to ElGamal Encryption

Research Background

The ElGamal encryption algorithm [1] is one of the most famous and important public key encryption algorithms. ElGamal encryption is IND-CPA secure under the DDH assumption but does not possess IND-CCA2 security. Previous research [2] has proven the IND-CCA1 security of ElGamal encryption under the AGM model (algebraic group model), which imposes certain restrictions on the adversary’s behavior. However, the IND-CCA1 security of ElGamal encryption in the standard model, which imposes no restrictions on adversary behavior, remains an open problem for a long time. This paper aims to study and resolve this issue.

Contributions and Conclusions of the Paper

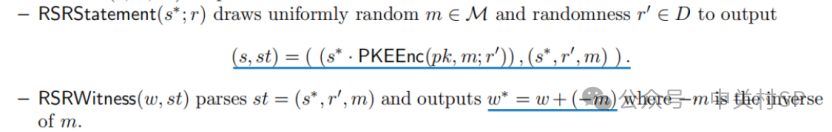

(1) This paper introduces a primitive called RRR relations, which abstracts the ciphertext c and plaintext m of the encryption algorithm into a relation pair (s, w) consisting of a statement s and a witness w. One of the core properties of RRR relations is the existence of a pair of algorithms RSRStatement(s; r) and RSRWitness(w’, st). The RSRStatement algorithm takes the input statement s and outputs a re-randomized statement s’ along with a private state st to store s and the random numbers used during the execution of the RSRStatement algorithm; the RSRWitness algorithm takes as input the witness w’ regarding the statement s’ and the private state st, and outputs the witness w of the statement s stored in the private state st. This paper also introduces the concept of sRRR relations (strong RRR), which adds an additional algorithm RSRTest to check whether w is a witness for the statement s stored in the private state st (requiring the random numbers stored in st as input).

(2) This paper proves, based on meta-reduction techniques, that there does not exist a simple reduction algorithm B (which can only call one adversary algorithm instance A and is not allowed to rewind algorithm A) that can reduce the OW-CCA1 security of RRR relations under the condition of accessing t+1 decryption oracles to an interactive complexity assumption tICA (t-Interactive Complexity Assumptions) that can access t times; that is, there does not exist a simple reduction algorithm B that can break the tICA hard assumption by calling an adversary A that breaks the OW-CCA1 security of RRR relations under the condition of accessing t+1 decryption oracles. This paper further proves that there does not exist a Turing reduction algorithm B (which can call at most u adversary algorithm instances A and is allowed to rewind algorithm A) that can reduce the OW-CCA1 security of sRRR relations under the condition of accessing t+u decryption oracles to tICA.

(3) This paper categorizes some common encryption algorithms into two classes: semi-homomorphic encryption algorithms (such as ElGamal encryption) and homomorphic one-way bijection functions (such as RSA encryption). It further demonstrates that both classes of encryption algorithms can construct sRRR relations, ultimately proving that ElGamal encryption cannot be proven to be OW-CCA1 secure through Turing reduction algorithms, nor can it prove stronger IND-CCA1 security.

Main Ideas

First, it explains why the ElGamal encryption algorithm is an RRR relation. As shown in the figure below, since the ElGamal encryption algorithm is a semi-homomorphic encryption algorithm, the RSRStatement algorithm can randomly sample a m and a random number r’, and the ciphertext obtained from public key encryption is multiplied by the input statement s* to obtain a new statement s. Due to the semi-homomorphic property, the witness w of s is equivalent to the witness w* of s* plus m; correspondingly, the RSRWitness algorithm can recover w* by calculating w-m.

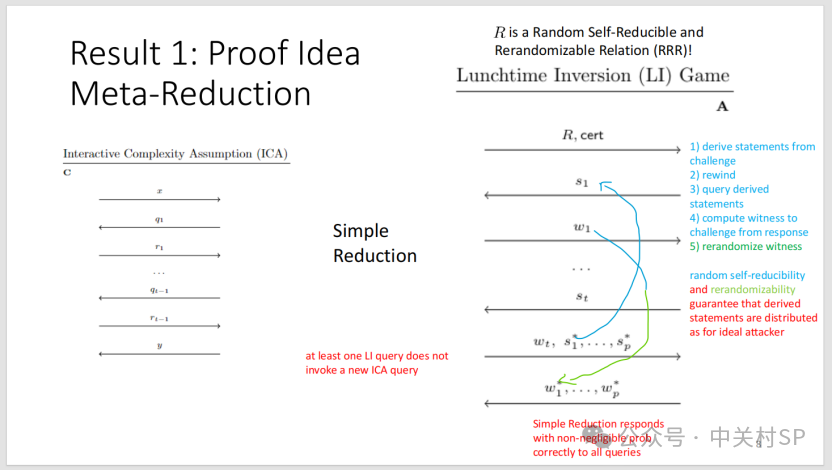

Next, a brief outline is given to explain why there does not exist a simple reduction algorithm B that can reduce the OW-CCA1 security of RRR relations under the condition of accessing t+1 decryption oracles to tICA, as illustrated in the figure below. The scenario extended to Turing reduction can be found in the original paper.

(1) Using proof by contradiction, if there exists a simple reduction algorithm B that can reduce the OW-CCA1 security of RRR relations under the condition of accessing t+1 decryption oracles to tICA, it would mean that if there exists an adversary algorithm A that can break the OW-CCA1 security of RRR relations under the condition of accessing t+1 decryption oracles, then B can break the tICA assumption by calling A.

(2) From the properties of adversary algorithm A, when B can simulate t+1 queries to the decryption oracle for A, A can return the decryption values {w*_i} for p challenge statements {s*_i}. In the standard model, adversary A is arbitrary, so assume there exists an ideal adversary whose computational power is unbounded, and the algorithm RSample generating the t+1 queries to the decryption oracle is uniformly sampled. Since the ideal adversary A has unbounded computational power, it can guarantee that it can return the correct challenge values without relying on the results of the decryption oracle queries; since the algorithm RSample is known, the ideal adversary A can simulate the generation of the queries to the decryption oracle.

(3) To break tICA, the reduction algorithm B also needs to provide a correct answer for some challenge value. One strategy is that B can succeed in challenging without relying on A’s output, which means there exists a polynomial algorithm that can directly break tICA, contradicting the security assumption of tICA; thus, B can only attempt to use the output of the ideal adversary A to provide the required answer. However, the condition for A to provide output is that B must first answer A’s t+1 uniformly generated queries to the decryption oracle. B can transform A’s queries into queries to the ICA answering oracle and obtain corresponding answers, but can access at most t times; this means that if B has a non-negligible probability of successfully reducing, then B has a non-negligible probability of answering A’s t+1 queries, which also implies that B has a non-negligible probability of successfully answering at least once A’s query without relying on the queries to the ICA answering oracle.

(4) To prove the required conclusion, construct a meta-reduction algorithm M, which can call and rewind the reduction algorithm B while simulating an ideal adversary A for B. M first simulates A’s t+1 queries sent to B through the RSample algorithm. If B can answer, M also needs to simulate the final output value of the ideal adversary A with unbounded computational power. M can first save the current state of B as st_0, then rewind B to the state before answering each of A’s query values, and send the re-randomized statement s obtained from the RSRStatement algorithm to B. From the discussion in (3), B has a non-negligible probability of successfully answering the query value s and outputting w without relying on the queries to the ICA answering oracle. M then calls the RSRWitness algorithm to obtain the witness w* for s, and then rewinds B back to state st_0, using w* as the final return value for the ideal adversary A to B, allowing B to successfully break the tICA hardness assumption.

This means that if there exists such a simple reduction algorithm B that can reduce the OW-CCA1 security of RRR relations under the condition of accessing t+1 decryption oracles to tICA, then the meta-reduction algorithm M can directly break the tICA hardness assumption by calling B. This is essentially because if such a reduction algorithm B exists, then B has a non-negligible probability of successfully answering at least once the ideal adversary A’s query without relying on the queries to the ICA answering oracle, and this query is uniformly generated, which implies that B can essentially answer the challenge values in the tICA challenge game, contradicting the tICA hardness assumption.

References

[1] ElGamal, T.: A public key cryptosystem and a signature scheme based on discrete logarithms. In: Blakley, G.R., Chaum, D. (eds.) CRYPTO’84. LNCS, vol. 196, pp. 10–18. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, Santa Barbara, CA, USA (Aug 19–23, 1984)

[2] Fuchsbauer, G., Kiltz, E., Loss, J.: The algebraic group model and its applications. In: Shacham, H., Boldyreva, A. (eds.) CRYPTO 2018, Part II. LNCS, vol. 10992, pp. 33–62. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, Santa Barbara, CA, USA (Aug 19–23, 2018).

The schematic diagram of the above scheme is excerpted from the paper author’s report. The paper contains more observations and findings, and interested readers are encouraged to read the original text in depth.

Original link:

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-58737-5_10

(Thanks to @今将图南 for the contribution)