TCP HTTP UDP:

All are communication protocols, which are the rules followed during communication. Only when both parties “speak” according to these rules can they understand or serve each other.

Relationship Between TCP, HTTP, and UDP:

TCP/IP is a suite of protocols, divided into four layers: network interface layer, network layer, transport layer, and application layer.

At the network layer, there are IP, ICMP, ARP, RARP, and BOOTP protocols.

At the transport layer, there are TCP and UDP protocols.

At the application layer, there are protocols such as FTP, HTTP, TELNET, SMTP, DNS, etc.

Therefore, HTTP itself is a protocol that serves as a transmission protocol for transferring hypertext from a web server to a local browser.

Socket:

This is a communication pipeline created to implement the above communication process. Its true representation is a communication process between the client and server, where both processes communicate through the socket, and the communication rules follow the specified protocol. A socket is merely a connection mode, not a protocol. TCP and UDP are, simply put (though not precisely), the two most basic protocols, with many other protocols based on these two. For example, HTTP is based on TCP. A socket can create a TCP connection or a UDP connection, meaning that a socket can create connections for any protocol since other protocols are based on these.

Next, we will mainly look at the protocols closely related to our internet life: HTTP.

What is the HTTP Protocol?

HTTP stands for HyperText Transfer Protocol, and it has been widely used on the WWW since 1990. It is currently the most used protocol on the WWW. HTTP is an application layer protocol, and when you browse the web, data is sent and received between the browser and the web server via HTTP over the Internet. HTTP is a stateless protocol based on a request/response model, which is what we commonly refer to as Request/Response.

URL:

URL (Uniform Resource Locator) addresses are used to describe a resource on the network, with the basic format as follows:

schema://host[:port#]/path/…/[?query-string][#anchor]

scheme specifies the protocol used at a lower level (e.g., http, https, ftp)

host is the IP address or domain name of the HTTP server

port# is the default port for the HTTP server, which is 80. In this case, the port number can be omitted. If another port is used, it must be specified, for example, http://www.cnblogs.com:8080/

path is the path to the resource being accessed

query-string is the data sent to the HTTP server

anchor is the anchor

An example of a URL:

http://www.mywebsite.com/sj/test/test.aspx?name=sviergn&x=true#stuff

Schema: http

host: www.mywebsite.com

path: /sj/test/test.aspx

Query String: name=sviergn&x=true

Anchor: stuff

HTTP Request/Response:

First, let’s look at the structure of the Request message, which is divided into three parts:

The first part is called the Request line,

The second part is called the Request header,

The third part is the body. There is a blank line between the header and the body,

The first line’s Method indicates the request method, such as “POST” or “GET”. The Path-to-resource indicates the requested resource, and Http/version-number indicates the version of the HTTP protocol.

When using the “GET” method, the body is empty.

For example, the request for opening the homepage of Blog Park is as follows:

GET http://www.cnblogs.com/ HTTP/1.1

Host: www.cnblogs.com

Abstract concepts can be difficult to comprehend; we often feel they are intangible. As the saying goes, seeing is believing. We can understand and remember things better when we see them in reality. Today, we will use Fiddler to take a practical look at the Request and Response.

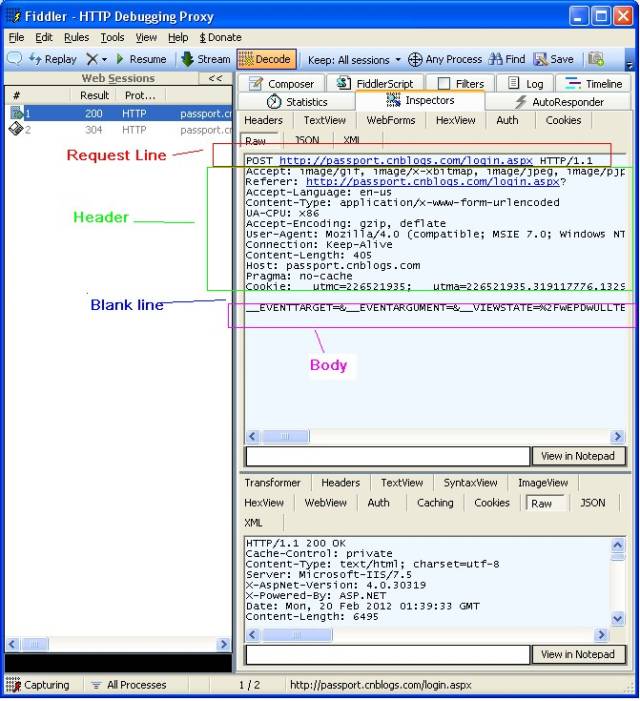

Next, we will open Fiddler to capture a login Request for Blog Park and analyze its structure. In the Inspectors tab, we can see the complete Request message in Raw format, as shown in the image below:

Accept:

Function: The media types that the browser can accept,

For example: Accept: text/html indicates that the browser can accept the type returned by the server as text/html, which is what we commonly refer to as an HTML document.

If the server cannot return data of type text/html, it should return a 406 error (non-acceptable).

The wildcard * represents any type.

For example, Accept: */* indicates that the browser can handle all types (generally, browsers send this to the server).

Referer:

Function: Provides context information about the server for the Request, telling the server from which link the request came. For example, if I link to a friend’s site from my homepage, his server can track how many users click on the link from my homepage daily through the HTTP Referer.

For example: Referer:http://translate.google.cn/?hl=zh-cn&tab=wT

Accept-Language:

Function: The browser declares the language it accepts.

The difference between language and character set: Chinese is a language, and Chinese has multiple character sets, such as big5, gb2312, gbk, etc.;

For example: Accept-Language: en-us

Content-Type:

Function:

For example: Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Accept-Encoding:

Function: The browser declares the encoding methods it accepts, usually specifying compression methods, whether it supports compression, and what compression methods (gzip, deflate) are supported (note: this is not just character encoding);

For example: Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

User-Agent:

Function: Tells the HTTP server the name and version of the operating system and browser used by the client.

When we log into forums online, we often see welcome messages that list the name and version of our operating system and the name and version of the browser we are using. This often amazes many people; in fact, the server application obtains this information from the User-Agent request header field. The User-Agent request header field allows the client to inform the server about its operating system, browser, and other attributes.

For example: User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 5.1; Trident/4.0; CIBA; .NET CLR 2.0.50727; .NET CLR 3.0.4506.2152; .NET CLR 3.5.30729; .NET4.0C; InfoPath.2; .NET4.0E)

Connection:

For example: Connection: keep-alive. After a webpage has been fully loaded, the TCP connection used to transport HTTP data between the client and server will not close. If the client accesses another webpage on this server, it will continue to use the already established connection.

For example: Connection: close indicates that after a Request is completed, the TCP connection used to transport HTTP data between the client and server will close. When the client sends another Request, a new TCP connection must be established.

Content-Length:

Function: Indicates the length of the data sent to the HTTP server.

For example: Content-Length: 38

Host: (This header field is required when sending a request)

Function: The request header field is mainly used to specify the Internet host and port number of the requested resource, which is usually extracted from the HTTP URL.

For example: When we enter http://www.guet.edu.cn/index.html in the browser, the request message sent by the browser will contain the Host request header field, as follows:

Host: http://www.guet.edu.cn

Here, the default port number 80 is used. If a port number is specified, it becomes: Host: specified port number

Pragma:

Function: Prevents the page from being cached. In the HTTP/1.1 version, it has the same function as Cache-Control:no-cache.

Pragma has only one usage, for example: Pragma: no-cache

Cookie:

Function: The most important header, sends the value of the cookie to the HTTP server.

Accept-Charset:

Function: The browser declares the character set it accepts, which corresponds to the various character sets and encodings introduced earlier, such as gb2312, utf-8 (usually when we say Charset, it includes the corresponding character encoding scheme);

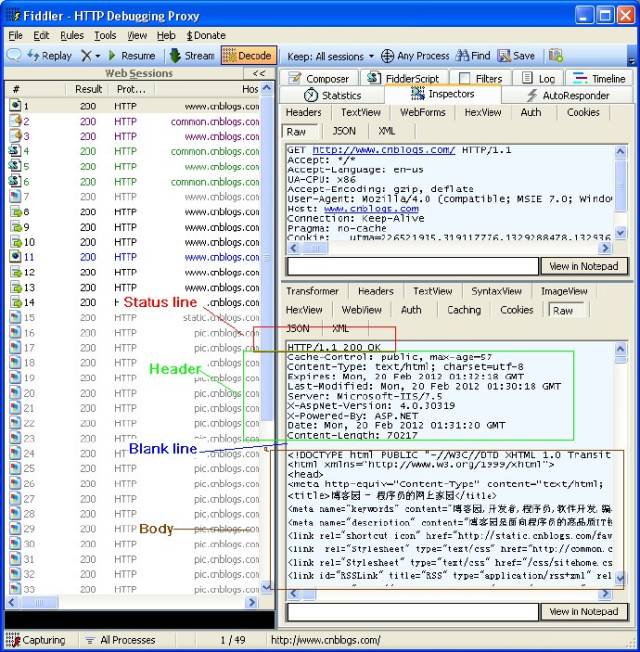

Now let’s look at the structure of the Response message, which is basically the same as the structure of the Request message. It is also divided into three parts:

The first part is called the Response line,

The second part is called the Response header,

The third part is the body. There is also a blank line between the header and the body,

Structure as shown in the image below:

HTTP/version-number indicates the version of the HTTP protocol, and status-code and message can be found in the next section [Status Codes] for detailed explanation.

We use Fiddler to capture a Response for the homepage of Blog Park and analyze its structure. In the Inspectors tab, we can see the complete Response message in Raw format:

Cache-Control:

Function: This is a very important rule. It specifies the caching mechanism followed by Response-Request. The meanings of various directives are as follows:

Cache-Control: Public can be cached by any cache.

Cache-Control: Private content can only be cached in private caches.

Cache-Control: no-cache means that all content will not be cached.

There are other usages, but I do not understand their meanings; please refer to other materials.

Content-Type:

Function: The web server tells the browser the type and character set of the object it is responding with.

For example:

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Content-Type: text/html; charset=GB2312

Content-Type: image/jpeg

Expires:

Function: The browser will use the local cache within the specified expiration time.

For example: Expires: Tue, 08 Feb 2022 11:35:14 GMT

Last-Modified:

Function: Indicates the last modification date and time of the resource. (For examples, see the previous section’s If-Modified-Since example)

For example: Last-Modified: Wed, 21 Dec 2011 09:09:10 GMT

Server:

Function: Indicates the software information of the HTTP server.

For example: Server: Microsoft-IIS/7.5

X-AspNet-Version:

Function: If the website is developed using ASP.NET, this header indicates the version of ASP.NET.

For example: X-AspNet-Version: 4.0.30319

X-Powered-By:

Function: Indicates what technology the website is developed with.

For example: X-Powered-By: ASP.NET

Connection:

For example: Connection: keep-alive. After a webpage has been fully loaded, the TCP connection used to transport HTTP data between the client and server will not close. If the client accesses another webpage on this server, it will continue to use the already established connection.

For example: Connection: close indicates that after a Request is completed, the TCP connection used to transport HTTP data between the client and server will close. When the client sends another Request, a new TCP connection must be established.

Content-Length:

Indicates the length of the entity body, represented as a decimal number stored in bytes. During the data downlink process, the Content-Length must be pre-cached on the server before all data is sent to the client.

For example: Content-Length: 19847

Date:

Function: The specific time and date the message was generated.

For example: Date: Sat, 11 Feb 2012 11:35:14 GMT

HTTP Protocol’s GET and POST:

The HTTP protocol defines many methods for interacting with the server, the most basic of which are GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE. A URL address is used to describe a resource on the network, and the HTTP methods GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE correspond to the four operations of querying, modifying, adding, and deleting this resource. The most common methods are GET and POST. GET is generally used to retrieve/query resource information, while POST is generally used to update resource information.

Let’s look at the differences between GET and POST:

1. Data submitted by GET is placed after the URL, separated by a ?, with parameters connected by &. For example: EditPosts.aspx?name=test1&id=123456. The POST method places the submitted data in the body of the HTTP packet.

2. Data size submitted by GET is limited (due to browser URL length restrictions), while POST has no limitations on data size.

3. GET requires Request.QueryString to obtain the variable values, while POST uses Request.Form to get the variable values, meaning GET passes values through the address bar, while POST passes values through form submission.

4. Submitting data via GET can lead to security issues. For example, when submitting data via a login page using GET, the username and password will appear in the URL. If the page can be cached or if someone else can access this machine, that user’s account and password can be obtained from the history.

(Content sourced from the internet, copyright belongs to the original author)

Disclaimer:If there are any copyright issues, please contact us for removal!

No individual or organization shall bear any legal responsibility.

Recommended Reading:

Benefits Coming! Schneider SoMachine Course Available for Free Learning

2019 Industrial Automation Employment Trends and Comprehensive Analysis of Domestic Universities

The first batch of IAAT certificates has been issued, please check your receipts!

Summary of RS485 and Modbus Communication Protocols, everything you want is here!

For detailed course inquiries:

Teacher Li 13395310291 (same number on WeChat)

Technical communication group:536682860 (QQ group)