This article is adapted from the official account: CLIMB – Center for Lifelong Development of Brain and Mind.

In our daily lives, we are constantly learning new things, but it is often difficult to remember everything we have learned. To enhance our memory capacity, we can think in a way that links several pieces of information together, allowing us to remember only a small amount of information. The brain has two ways to achieve this. One is called chunking, which allows us to retain more information in our memory bank in a short time. The prefrontal cortex is the part of the brain that helps us achieve chunking. When we need to remember information for a long time, another part of the brain, the limbic cortex, performs a similar process called unitization, linking two or more items together through some relationship. These learning methods can help us remember a lot of information, such as when preparing for exams!

We often think that more is always better: we want more money, want to eat more fries, or want to know more to perform better in school exams. However, when it comes to memory, how can we remember more when we have many things to remember? Trying to remember many fragmented pieces of information is difficult. Scientists have told us that if we piece together many fragments of information into a whole, we can remember better. Integrating, linking, and connecting information in our brain is called binding. We will tell you how to use two different types of binding to improve your memory, and we will also share some findings from scientists about memory and the brain.

We often think that more is always better: we want more money, want to eat more fries, or want to know more to perform better in school exams. However, when it comes to memory, how can we remember more when we have many things to remember? Trying to remember many fragmented pieces of information is difficult. Scientists have told us that if we piece together many fragments of information into a whole, we can remember better. Integrating, linking, and connecting information in our brain is called binding. We will tell you how to use two different types of binding to improve your memory, and we will also share some findings from scientists about memory and the brain.

Exercising Our Working Memory

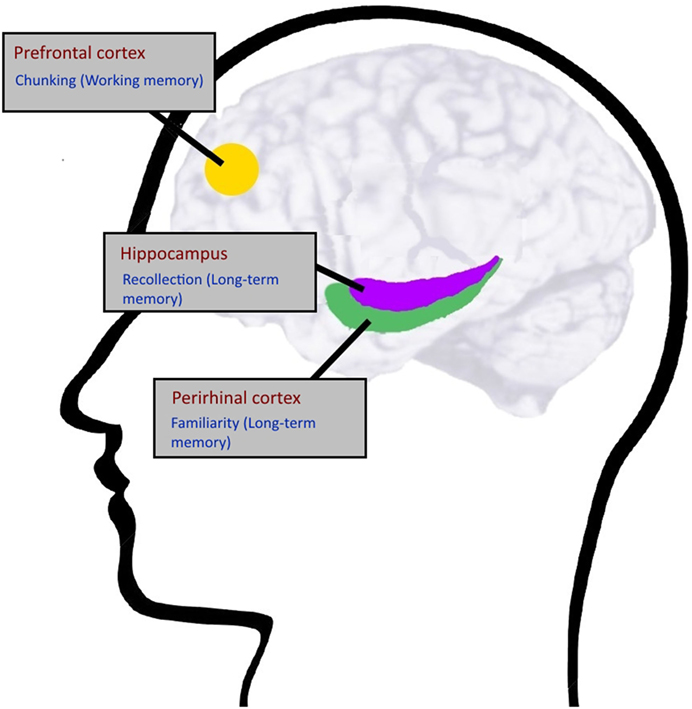

When scientists talk about working memory, they refer to a type of memory that only lasts a very short time in our minds, such as a few seconds; you only need to hold onto this information until you have dealt with the situation or problem, and then you can forget it. Unless we do something to remember this information, such as repeating it out loud over and over, it will quickly be forgotten. The rapid loss of information in working memory is because it can only hold a small amount of information, about seven items at a time. Information cannot stay in working memory forever. Things either need to be forgotten or moved from working memory to more permanent memory to make room for new information.Now imagine you receive a gift card from your favorite store, and you want to use it to buy something you really want online. At checkout, you need to read the long number on the gift card and enter it on the store’s website. In other words, you need to keep the gift card number in your working memory. Let’s assume this number is 977429112005—quite a long number! Keeping such a long number in your mind is very difficult, even for a few seconds. What if you realize not to think of each digit separately, but to break the number into several parts? This means you can use a memory technique called chunking. This technique is called chunking because the information is divided into several parts or “chunks”, such as 97-742-911-2005, where each chunk may have special significance to you. For example, you might have scored 97 on a recent science test, 742 could be the highway number closest to your city, 911 is the emergency number (in the USA), and 2005 is your birth year. Now, you don’t need to remember all these digits at once; you just need to remember science, highway, emergency, and birth year. Isn’t that easier? By chunking, you free up more space in your working memory because all these digits only take up four spaces instead of twelve. How useful is that! You can also use chunking for other things, like when your friend asks you to grab a book from her locker. Your friend quickly gives you the locker combination, and you just need to remember that number until you open the locker, and then you can forget it. What else do you think you could use chunking to remember for a short time? Scientists have found that whenever we use working memory, we engage a brain region called the prefrontal cortex. It is located at the front of your brain, above your eyes and behind your forehead. You can see this part of the brain in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Diagram of important brain regions supporting working memory (prefrontal cortex) and long-term memory (hippocampus and limbic cortex).This figure is adapted from: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/synaptic/pathways/Scientists are curious about how the prefrontal cortex works when we use chunking to enhance our working memory[1]. Scientists used a machine that measures brain activity to observe how people’s brains work when using chunking to remember information or not. To what extent do you think using chunking affects how much these people use their prefrontal cortex? Do you think people use their prefrontal cortex more or less when using chunking to remember information?As illustrated in the gift card example above, when information is chunked, the amount of information you need to remember is less. If the prefrontal cortex is used to store information, then when people use “chunking”, they might use the prefrontal cortex less frequently because the amount of information to remember is reduced. However, this did not happen in the experiment. Scientists found that people using chunking memory techniques used their prefrontal cortex more than those not using chunking. Even though people need to remember less information when using chunking, they require more thinking, planning, and strategies to perform chunking. Therefore, from this experiment, we know that the prefrontal cortex is not responsible for storing information in working memory, but rather for planning and thinking, enabling working memory to chunk.

Diagram of important brain regions supporting working memory (prefrontal cortex) and long-term memory (hippocampus and limbic cortex).This figure is adapted from: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/synaptic/pathways/Scientists are curious about how the prefrontal cortex works when we use chunking to enhance our working memory[1]. Scientists used a machine that measures brain activity to observe how people’s brains work when using chunking to remember information or not. To what extent do you think using chunking affects how much these people use their prefrontal cortex? Do you think people use their prefrontal cortex more or less when using chunking to remember information?As illustrated in the gift card example above, when information is chunked, the amount of information you need to remember is less. If the prefrontal cortex is used to store information, then when people use “chunking”, they might use the prefrontal cortex less frequently because the amount of information to remember is reduced. However, this did not happen in the experiment. Scientists found that people using chunking memory techniques used their prefrontal cortex more than those not using chunking. Even though people need to remember less information when using chunking, they require more thinking, planning, and strategies to perform chunking. Therefore, from this experiment, we know that the prefrontal cortex is not responsible for storing information in working memory, but rather for planning and thinking, enabling working memory to chunk.

Having a Good Long-Term Memory

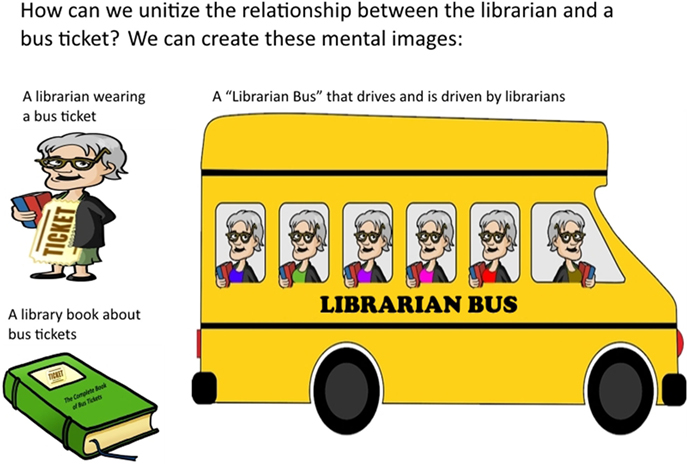

Now we know how chunking helps us have better working memory. When we only need to remember something in our minds for a short time, increasing the capacity of working memory is very useful. However, many times, we need to store information for more than a few seconds so that we can recall it later. When we need to remember something for a long time, we use long-term memory. An example is recalling a baseball game you won or remembering the moment you felt a cool breeze on your face after a hot summer day. Long-term memory is not perfect, and sometimes it takes a lot of effort to remember certain things, or else we forget. So how can we achieve better long-term memory? First, we need to understand more about long-term memory.Scientists have shown that there are two methods to awaken things stored in long-term memory. These methods use different brain regions and require different efforts.One is called recollection, which makes it difficult for us to think[2]. We can use recollection to remember any specific thing. For example, if you saw your school librarian at a coffee shop on Saturday, you would remember that she is the librarian. When we need to remember two or more related things, we can also use the method of recollection. For instance, you must remember that the school librarian gave you a bus ticket home. In this case, you need to remember not only the librarian and the bus ticket but also the relationship between the two. Scientists have found that the part of the brain used to remember and recall these relationships is called the hippocampus. This brain region is shaped like a seahorse and is buried deep within the brain. You can see the location of the hippocampus in Figure 1.The second method of extracting information from long-term memory is familiarity, which is a faster, easier, and more relaxed way to remember[2]. When we remember a single thing, we can use familiarity, but when we need to remember the relationships between several things, we usually do not use familiarity. At that time, we need to use recollection. (As mentioned earlier, we can also use “recollection” to remember a single thing, but this is more difficult, so we usually try to use “familiarity” whenever possible.) In the case of familiarity, when you see the librarian at the coffee shop on Saturday, you may not clearly recall how you know her, but just remember that you have seen her somewhere. However, if your mom says, “Isn’t that your school librarian?” then your brain will think that this is correct because it feels right. When we use familiarity, we are using a part of the brain called the limbic cortex. The limbic cortex is very close to the hippocampus and receives information from other parts of the brain through our five senses; you can see its location in Figure 1.If we could use familiarity in a quick and easy way to remember the relationships between multiple things instead of using the more difficult method of recollection, what would happen? If we could do that, we could improve long-term memory because it would be easier to remember information. Scientists have found that we can use a way of thinking called unitization to use familiarity instead of recollection[3-5]. Unitization is a method of combining several pieces of information into one piece of information stored in our long-term memory. It works by establishing (or imagining) a new important connection—linking the things we want to remember together. Scientists have found that when we use unitization to combine things, we use the limbic cortex more than when we do not use unitization.Returning to the previous example, suppose you need to remember that the school librarian gave you a bus ticket home. You can combine these two meanings to define one meaning. So, you think, “librarian bus,” and then imagine this is a special bus that takes librarians to the local library. You can visualize an image similar to what is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Examples of images you might create in your mind to unitize the relationship between the librarian and the bus ticket. A librarian wearing a bus ticket, a library book about bus tickets, and a “librarian bus” driven by the librarian.When you need to retrieve the ticket, if you used unitization, your brain will immediately recognize that the librarian “feels right,” using the important connection you imagined to link the two things together. So now, you don’t need to think so much about where to get your ticket; you will immediately realize that the bus ticket and the librarian are a good combination. For more examples of binding multiple things to one idea, see the column.

Examples of images you might create in your mind to unitize the relationship between the librarian and the bus ticket. A librarian wearing a bus ticket, a library book about bus tickets, and a “librarian bus” driven by the librarian.When you need to retrieve the ticket, if you used unitization, your brain will immediately recognize that the librarian “feels right,” using the important connection you imagined to link the two things together. So now, you don’t need to think so much about where to get your ticket; you will immediately realize that the bus ticket and the librarian are a good combination. For more examples of binding multiple things to one idea, see the column.

Column: What unitization programs can we adopt?

You already know that when we use a concept or new definition to bind two pieces of information together, these pieces can become a whole and work as a unit together. However, there are other ways to form unitized thoughts. Here are a few examples:Try to imagine these two objects interacting. For example, if you want to remember that you need to meet the librarian because she is distributing bus cards, try to imagine the librarian driving the bus, and she is also all the passengers on the bus. It doesn’t matter if the image is unrealistic, as long as the two things interact in some way.You can also try to establish some realistic connections between these items. For example, if you know that the librarian always takes the bus to work, then when you store and later use the two things “librarian” and “bus,” try to connect them with this information. This will increase your ability to see them as one.It is easier to unitize items presented to the same sensory modality (auditory, visual, etc.) than to items presented to different sensory modalities. So, if you want to remember the sound of the librarian when you see the bus passing by, try to create a visual image of the librarian and the bus in your mind, or imagine the sound of the librarian speaking as the bus rushes by.

Conclusion and Outlook

Using a way of thinking that links or binds several pieces of information together means we can store more information in our memory, and it can help us remember information better. The type of memory used to connect information together may be very different from the type of thinking used for a single piece of information, and we use different parts of our brain for these different types of memory. When we link things together to remember information in working memory for a short time, we call it “chunking memory.” We use the prefrontal cortex of the brain to do this, which is responsible for planning and organizing our working memory. When information binding helps us store things in long-term memory for a long time, we call it “unitization.” Unitization allows us to use familiarity to quickly and easily (automatically) remember information, and we use a part of the brain called the limbic cortex to do this. Using these different connections can help us remember, such as when we prepare for exams.

Glossary

Binding: Integrating, linking, and connecting information together so that there are not so many small pieces of information. Two examples of binding are chunking and unitization.

Working Memory: This type of memory only lasts a very short time in our minds, such as a few seconds.

Chunking: A memory technique that groups several items in working memory. It is supported by the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

Prefrontal Cortex: A part of the brain located at the front of the head, above the eyes and behind the forehead. It is used when we think and plan to enhance our working memory, such as when using chunking memory.

Long-Term Memory: A memory storage system for storing information for a long time.

Recollection: A way that allows us to think carefully about information. We can use it to remember not only a single thing but also the relationship between two or more things. It is supported by the hippocampus of the brain.

Hippocampus: The part of the brain responsible for recollection. It is located deep within the brain and shaped like a seahorse.

Familiarity: A quick, convenient, and easy way to recall something. You may not have a clear memory of what you are trying to remember, but it “feels” right. It is supported by the limbic cortex of the brain.

Limbic Cortex: The part of the brain that supports familiarity. It is located near the hippocampus and receives information from other parts of the brain through our five senses.

Unitization: A method of combining several pieces of information into one piece of information to store in our long-term memory.

References

[1] Bor, D., Duncan, J., Wiseman, R. J., and Owen, A. M. 2003. Encoding strategies dissociate prefrontal activity from working memory demand. Neuron 37:361–7.[2] Yonelinas, A. P. 2002. The nature of recollection and familiarity: a review of 30 years of research. J. Mem. Lang. 46:441–517.[3] Haskins, A. L., Yonelinas, A. P., Quamme, J. R., and Ranganath, C. 2008. Perirhinal cortex supports encoding and familiarity-based recognition of novel associations. Neuron 59:554–60.[4] Bader, R., Mecklinger, A., Hoppstädter, M., and Meyer, P. 2010. Recognition memory for one-trial-unitized word pairs: evidence from event-related potentials. Neuroimage 50:772–81.[5] Tibon, R., Gronau, N., Scheuplein, A. L., Mecklinger, A., and Levy, D. A. 2014. Associative recognition processes are modulated by the semantic unitizability of memoranda. Brain Cogn. 92:19–31.

Original Article

Tibon R and Cooper E (2016) When One Is More Than Two: Increasing Our Memory. Front. Young Minds. 4:11.

Authors

Roni Tibon

Elisa Cooper

English Editor

Sabine Kastner

Young Reviewers

Easterly Parkway Elementary School

Chinese Translation

Qing Zhang

Chinese Editor

Xueru Fan

Chinese Reviewer

Xinian Zuo

———–End of Sharing———-–

Editor:Yezi

Reviewer: mingzlee7

Disclaimer: Some articles and information are sourced from the internet and do not represent the views of this subscription account or its authenticity. If the content involves copyright issues, please contact the editor Yezi immediately (WeChat ID: 1791438763), and we will take appropriate measures promptly. Original content from this subscription account requires authorization for reprinting, and the author and source must be indicated.