– ShenzhenWare –

Editor’s note: This article is sponsored by Sharp Corporation, and the editorial team of “Rocket Café” independently composed it, authorized for publication by Shenzhen Bay (Public ID: shenzhenware).

This article mainly narrates the story of Sharp’s founder, Tokuji Hayakawa, during the establishment of the company, from the invention of the mechanical pencil and the built-in turntable of the microwave oven to the liquid crystal display and mobile phones, all reflecting the artisan spirit of this founder and showcasing Sharp’s growth trajectory.

The author of “The Artisan Spirit: 30 Rules for Cultivating Top Talent,” Toshihiro Akiyama, is widely respected for his unique artisan cultivation system, emphasizing that a first-class mindset and talent refine first-class skills.

This description fits particularly well for Sharp’s founder, Tokuji Hayakawa. Born in 1893, it was a time less than twenty years into the Meiji Restoration, and the entire Japanese society was filled with a sense of striving to catch up with the West.

His family relied on making Japanese dining tables for a living while also doing sewing work, yet they still struggled financially, leading to Hayakawa being sent to a nearby fertilizer seller to be adopted. It is unclear whether it was fate or simply the poverty of the times, but when Hayakawa was three years old, his adoptive mother passed away, and he could not continue his education, ending up as a child laborer gluing matchboxes in a factory.

Although Hayakawa faced a challenging fate from birth, his artisan-like resilience gradually caught the attention of those around him. A neighbor who worked in metal processing noticed the boy and believed he had potential, inviting him to help at his shop, which inspired Hayakawa to embark on a path of technical processing and creative thinking.

At 19, Hayakawa (in 1912) started a metal processing factory with 50 yen in startup capital—40 of which were borrowed..

This factory might not strictly be considered the predecessor of Sharp since it was Hayakawa’s first entrepreneurial venture, but the factory invented the prototype of the modern faucet the following year and received licensing approval from the Tokyo Patent Office. With this funding, Hayakawa also spent 200 yen in 1914 to purchase a 1-horsepower motor, entering the realm of semi-automated production.

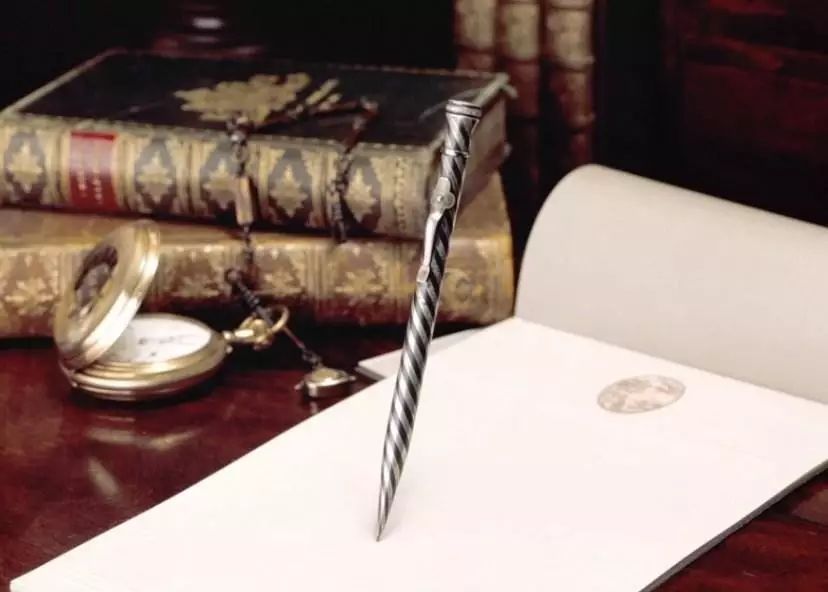

The origin of the name “Sharp” starts with the mechanical pencil.

Hayakawa’s metal processing factory, in addition to faucets, also took on many miscellaneous and stationery processing projects, with the popular metal nibs for fountain pens being a major project for Hayakawa’s factory. One day, Hayakawa received an order from a company to manufacture mechanical pencils. At that time, the design of mechanical pencils was not mature, leading to frequent issues with lead breakage or the entire pencil becoming unusable.

After receiving this order, Hayakawa applied his artisan spirit of striving for perfection, carefully disassembling and analyzing the prototype of the mechanical pencil, adding a very thin metal spring inside to solve the problem.

Hayakawa’s mechanical pencil

Thus, in 1915, Hayakawa obtained a patent from the Tokyo Licensing Bureau for the “Hayakawa Mechanical Pencil” (a reusable pencil). However, despite its practicality, the initial market promotion did not go smoothly; the general public considered the cold metal feel of the pencil incompatible with the aesthetics of traditional Japanese clothing, resulting in poor sales within Japan.

In contrast, during World War I, Europe faced a shortage of goods, leading to an influx of orders for these pencils from Europe and America. Hayakawa later thought, since this reusable pencil was so well-known in Europe and America, he would change the company name to the English name of this product—which is how the name “SHARP” originated.

If you think that Hayakawa’s career would be smooth sailing from then on, you would be greatly mistaken.

In 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake claimed the lives of Hayakawa’s two children, and his wife, Fumiko Hayakawa, was severely injured, while the factory’s machinery was almost completely destroyed. Unable to restart the factory, Hayakawa had to sell all the patents for the mechanical pencil to a Japanese stationery manufacturing company to repay debts.

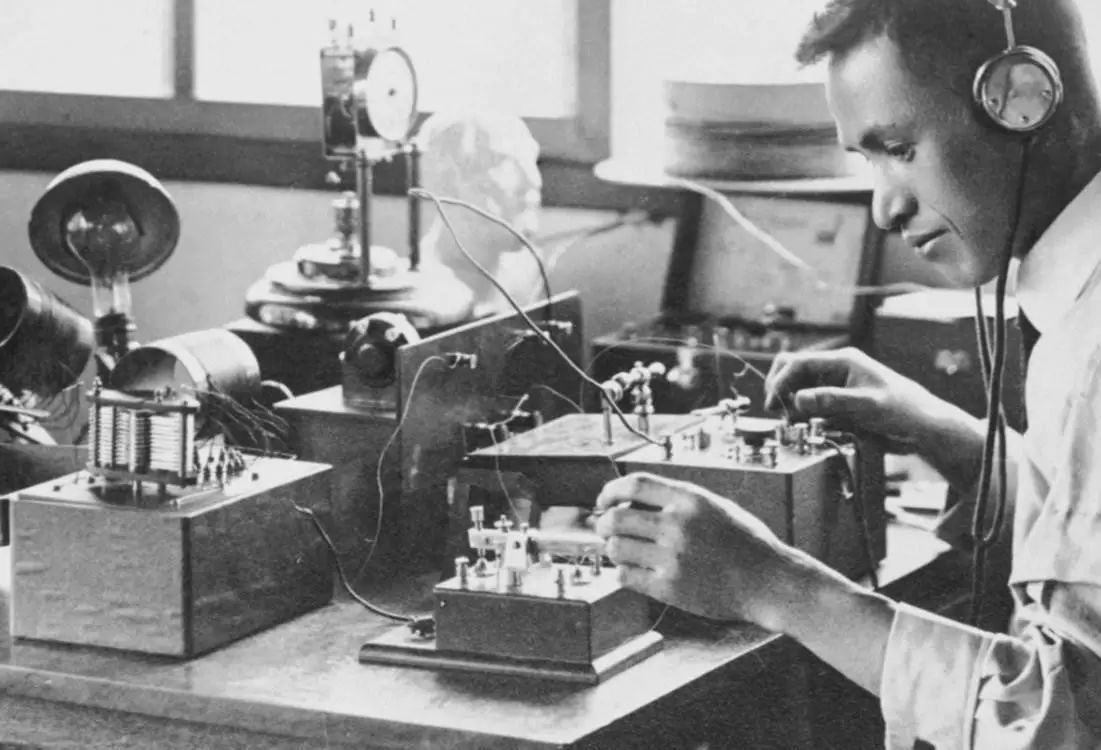

Rebirth after adversity: Launching the first electrical product, the “Radio”.

The following year, Hayakawa established the “Hayakawa Metal Industrial Research Institute” in Osaka, with the original intention of continuing the profit model of the previous metal processing factory, primarily producing fountain pen nibs. However, Hayakawa discovered another popular product in Europe and America at the time: the “Radio”.

At that time, Japan had no know-how regarding mineral radios, so even if he wanted to learn, there was no way. Hayakawa, relying on past experience, first bought two American-made radios, brought them back to the company, and had his colleagues disassemble and analyze them, eventually completing Japan’s first mineral radio in 1925.

In the same year, the Osaka Broadcasting Station (radio station) began trial operations, and this radio could clearly receive programs from the Osaka Broadcasting Station, which boosted Hayakawa and his colleagues’ confidence. This radio was also launched as Sharp’s first electrical product.

Facing giants, seeking the most suitable direction in the midst of impact and change.

From Hayakawa’s story, it can be observed that Sharp differs from the other two electrical giants, SONY (Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation) and PANASONIC (Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd.), in that entrepreneur Hayakawa was always seeking the most suitable direction in the midst of continuous impacts and changes.

Whether it was the initial transition from fountain pen nibs to producing mechanical pencils or from producing mechanical pencils to developing electrical products, Sharp seems to possess a DNA of the artisan spirit that grows stronger in adversity and embraces change.

Every adjustment Hayakawa made regarding the main product direction was based on his keen sense of discovering new trends and utilizing existing products, through professional techniques and the resilience to learn from failures, to identify blind spots in the creation and production processes, breaking through to a higher level. This logic has always been the core value of Sharp.

Japan’s first mass-produced microwave oven

For example, when microwave ovens were invented, manufacturers made a microwave oven similar to an oven, but the biggest problem encountered during use was that food was not heated evenly.

Thus, Sharp’s engineers thought of placing a rotating turntable inside the microwave oven, which, once started, would rotate along with it. This not only solved the problem of uneven heating but also became a standard feature of microwave ovens.

The birth of the star product, the liquid crystal screen, reignites the battle among the three electrical giants.

Another star product of Sharp, the liquid crystal screen, also stems from this artisan spirit. Sharp produced the latest semiconductor electronic computers, reigniting the battle among the three electrical giants after the Sharp radio.

In this battle, Sharp focused on the development of liquid crystal displays, and since 1973, liquid crystal screens have almost become synonymous with Sharp.

In this battle, Sharp, through its persistence with products and dedication to research and development, continuously stayed at the forefront of the liquid crystal display industry, just in time to meet the dramatic changes in global communication modes and tools. The demand for mobile phones for communication not only pursued thinner and clearer screens but also increased significantly.

In 2000, Kyocera and Sharp produced the first camera-equipped mobile phone, J-SH04. Mobile phones equipped with cameras and high-quality screens quickly became popular among young people..

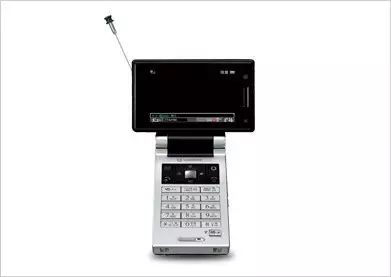

Sharp later developed the SH251is mobile phone, which featured a liquid crystal screen capable of displaying 3D images through an app. By 2006, as bandwidth and signal reception improved, the demand for watching television programs on mobile phones began to rise. Sharp then developed the top brand AQUOS from its television business, launching the 905SH mobile phone, which could receive television signals with ONE SEG.

The Aquos Keitai mobile phone launched by Sharp in 2006 could receive television signals.

Although the idea of mobile phones equipped with ONE SEG originated from another competing brand, Sanyo Electric, the 905SH improved upon the shortcomings of Sanyo’s products, such as adding a screen that could rotate 90 degrees and receiving electronic program guides from television stations, further proving Sharp’s artisan spirit of continuously seeking knowledge, innovation, and perfection.

The logic behind Sharp’s growth.

From the story of Tokuji Hayakawa and the development trajectory of Sharp, it can be observed that whether it is Tokuji Hayakawa or Sharp, the company has faced numerous challenges since its inception. However, an individual with an artisan spirit must first have confidence in their technical abilities and then carve out a new path from risks.

This model, or rather this artisan spirit, is also the DNA that Sharp people take pride in—overcoming setbacks and becoming stronger. In Sharp’s growth trajectory, the logic can be seen as:

-

Maturing existing technologies

-

Sensitivity to market trends

-

Recombining technology with market needs

-

Aiming for a leading position and achieving high objectives

If “artisan spirit” were to define the spirit of Sharp, it should be described as a “Smart Artisan Spirit.” They do not cling to tradition but integrate traditional technology with future vision, which is the core value of Sharp’s artisan spirit.■

Author of this article: Rocket Café

Editor: Jes

· ● Rocket Café Column ● ·