This is a story that witnesses “Nothing is Impossible” or “Impossible is Nothing”. Faced with a declining number of applicants for computer science, Eben Upton, the director of education at Cambridge University, was determined to reignite the next generation’s curiosity about computing with a gadget that sparked his childhood interest in programming. For this to happen, it had to be something that could be embedded in various common devices and be affordable enough.

The BBC’s report sparked a great deal of public interest, leading them to embark on a Don Quixote-like effort. Despite numerous complex challenges, Upton and his Raspberry Pi Foundation team ultimately overcame the difficulties, making this credit card-sized single-board computer the third best-selling computer globally.

When asked about the reason for Raspberry Pi’s success, Upton said that perhaps it was ignorance that allowed them to achieve something impossible. TechRepublic interviewed the Raspberry Pi development team and provided an in-depth report on the birth of this $35 microcomputer. The original author, Nick Heath, compiled it for readers.

The feeling of wanting to concentrate that morning was like being on the rack.

Eben Upton was referring to May 2011, when he felt the weight of public expectations on his shoulders after the $35 Raspberry Pi computer he co-developed was disclosed online.

After five years of relatively obscure tinkering with the design of this board, he suddenly realized that the number of people aware of the project had exploded; within just two days, early Raspberry Pi videos had garnered 600,000 views.

At first, Upton was delighted by the interest sparked by BBC technology correspondent Rory Cellan-Jones’s report, and he described it to his wife Liz, who doused his enthusiasm with harsh reality:

She told me, “You know you have to do this now, right?”

That was a difficult moment, realizing that they had already told everyone they were doing this, and they were now in too deep to back out. If it weren’t for Rory, they could have just been playing around.

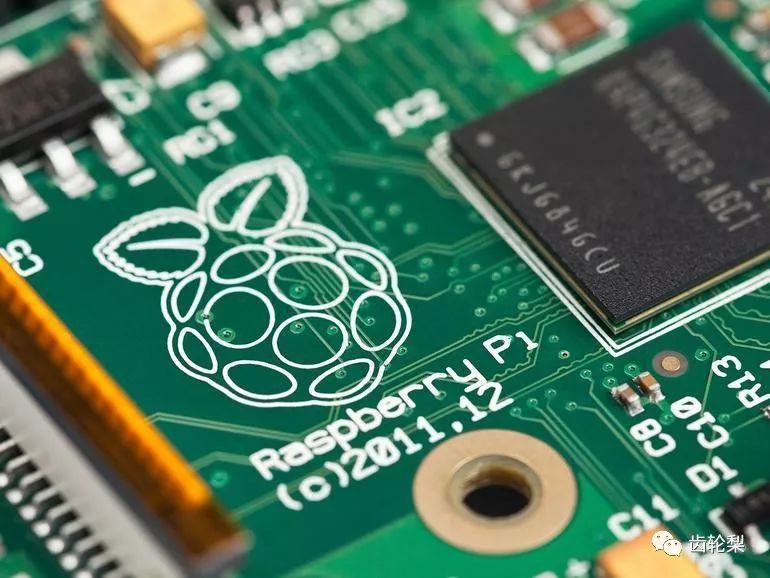

Today, Raspberry Pi has become a phenomenon, the third best-selling general-purpose computer worldwide. If you are interested in computing, it’s likely that you have already gotten your hands on one of these British-made boards plugged in somewhere. It has been embedded in laptops, tablets, and robots; it has even gone to the International Space Station for experiments; it has even appeared in mainstream media, in TV shows like “Mr. Robot” and movies like “Big Hero 6”. We have yet to mention its role in business, where Raspberry Pi is almost omnipresent, from thin clients to industrial control systems.

However, this success was by no means guaranteed. Raspberry Pi started from a sort of Don Quixote-like effort to reignite curiosity about computing in an era where a generation was immersed in technology but indifferent to its mechanisms. For Upton, the seed was planted in 2006 when he was a director of education at Cambridge University, feeling puzzled by the dwindling number of applicants for computer science.

The numbers were dismal, plummeting from 600 applications from 80-90 places at the turn of the century to only 250.

Faced with such disinterest, Upton couldn’t help but ask, “Where did all those applicants go?” and “How can we win them back?”

▴Eben Upton, photographed after being knighted (CBE) at the Queen’s birthday honors ceremony in 2016. Image: Raspberry Pi Foundation

He said, “We didn’t realize at the time that home computers that made programming easy in the 1980s were a significant source of talent for us.”

“As those machines disappeared in the 1990s, the children who could learn programming also vanished, and then ten years later we woke up to find no one was applying for our courses.”

“So, Raspberry Pi is a response to that. It was a very deliberate attempt to reboot the kind of machine I had when I was a kid.”

Upton grew up in the 1980s, when computers like the BBC Micro in the UK and the Commodore 64 in the US were trying to enter homes. For the average modern computer user, the BBC Micro seemed daunting: a brown, thick machine that booted up to a blinking cursor with no explanation of what to do next.

But for Upton and many children of the 1980s, that blinking cursor on an almost blank screen was an invitation to fill in the blanks, inviting them to input BASIC programming language to bring the BBC Micro to life with sound and color.

Fast forward 20 years, and the dominant computers on the market—game consoles and later tablets and smartphones—no longer invited them to create but urged them to consume.

Upton recalls a moment in 2007 at a bonfire party when an 11-year-old boy told him he wanted to be an electronic engineer, but was disappointed to find that there were no computers available for him to learn programming.

“I said, ‘Oh? What computer do you have?’ He said, ‘I have a Nintendo Wii.’ That made me feel awkward; this kid was so excited and showed such a strong interest in our profession, but he didn’t have a computer to program, not any form of computer. He just had a game console.”

At that time, Upton was a chip designer at Broadcom, working on a chip architecture system, and he realized he had the skills needed to address the trend of discouraging users from coding computers.

He said, “I had been developing small computers as a hobby for a long time. So, the ability to develop small computers, combined with the realization that the lack of small computers was a problem, was the spark that led to Raspberry Pi.”

Why is Raspberry Pi only $35?

The idea was to create a computer that was not only cheap but could also be disposed of almost casually, priced low enough that children wouldn’t fear carrying it around or connecting it with other hardware to develop their own electronic products.

Upton said, “It was important for us to make a computer that could be casually destroyed.”

“The price should be low enough that you wouldn’t feel like you were risking world destruction when connecting it with cables.”

However, pricing it that low posed challenges. In the mid-2000s, computers for $35 simply didn’t exist, and what Upton initially made looked almost nothing like the final Raspberry Pi.

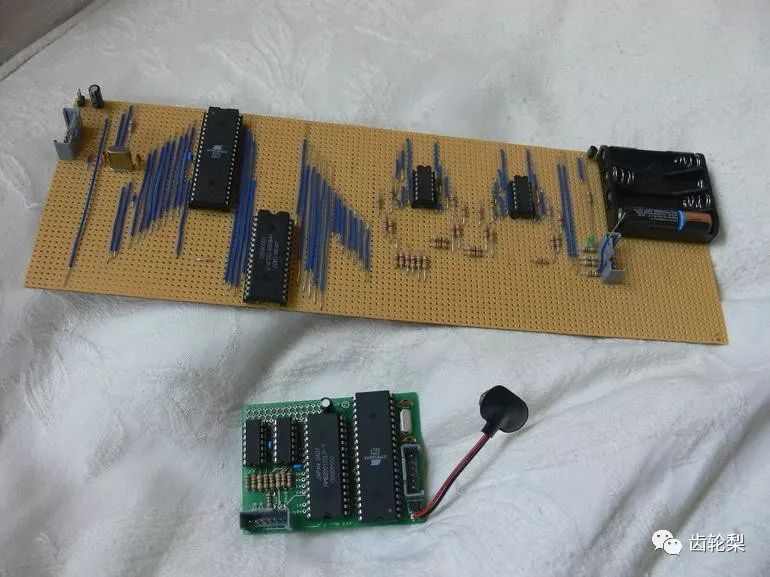

The first Raspberry Pi he tried in 2006 was so simple compared to the computer released six years later that it could be assembled by hand using off-the-shelf chips and components, and a soldering iron.

The prototype with an overly large processor and resistors looked like a relic from a bygone era—essentially replicating the capabilities of the BBC Micro that Upton had known as a child.

▴The first generation Raspberry Pi prototype, handmade by Eben Upton in 2006, which is very different from the computer launched in 2012. Image: Raspberry Pi Foundation

“The first thing you could call Raspberry Pi was developed on an Atmel microcontroller; it could render a bit of 3D graphics; its capabilities were roughly comparable to the BBC Micro, but you could make it yourself with a soldering iron. That was its advantage, something later Raspberry Pis couldn’t do.”

Upton didn’t pursue that design path because he felt it wasn’t powerful enough and the usability was poor. However, he didn’t lose the motivation to reignite interest in computer science and continued discussing solutions with engineer colleagues and scholars. In 2008, the project reached a critical point when Upton sat down with Cambridge University professor Alan Mycroft, electronic engineer Pete Lomas, and several others to start brainstorming the blueprint for a cheap computer tailored for children.

Lomas, the founder of the electronic design consultancy Norcott Technologies, designed the first generation Raspberry Pi’s printed circuit board (PCB). He described that meeting in October as the decisive moment for the birth of Raspberry Pi.

Lomas said, “Many of us had similar thoughts. It just needed that meeting to act as a catalyst for it to happen.”

He said their vision was to create a machine that could provide a window into how computers worked—not a sealed black box, but a board that children could learn about every component, feel the processor heat up when it worked, and delve into the open-source software code that ran on it.

The Origin of the Name Raspberry Pi

In 2008, we witnessed the first prototype created by Upton being called Raspberry Pi.

Although this second prototype was more powerful than the first handmade one, the 2008 machine was not yet a mature computer like Raspberry Pi; it only ran on Broadcom’s graphics processing unit (GPU) and vector processing unit (VPU)—these chips were also part of a larger computer system, which Upton called “something cobbled together on a Broadcom development board.”

Once again, that prototype reminded Upton of the BBC Micro he had always used while growing up. Although much more powerful than the machine from the 1980s, this prototype also booted up to a blinking cursor, except this time it ran Python code.

Upton said, “Just like the BBC Micro booted into BASIC, this one boots into some version of Python.” He said the name Pi came from that.

As for the word Raspberry, on one hand, he wanted to learn from the tradition of naming companies after fruits like Apple, Apricot Computers, and Acorn (the predecessor of chip manufacturer Arm and BBC Micro manufacturer), and on the other hand, it was a tongue-in-cheek nod to the project’s playful nature at the time.

Upton said, “There are many companies named after fruits, and ‘blowing a raspberry’ was also intentional.”

In early the following year, Upton, Lomas, Mycroft, Elite creator David Braben, and Cambridge University lecturers Jack Lang and Rob Mullins founded the Raspberry Pi Foundation, a charity focused on providing the knowledge and tools necessary to teach computer software and hardware creation worldwide.

▴Trustees at a board meeting in 2012: from left to right: Finance Director Martin Cartwright, Professor Alan Mycroft, Pete Lomas, David Braben, Eben Upton, and Jack Lang. Also pictured on the right is Alex Bradbury, who was the foundation’s chief Linux developer at the time. Image: Raspberry Pi Foundation

However, even though the name and foundation were in place, the design of the computer began to face difficulties. At such a low price, Upton and Lomas couldn’t find the right processor that met the demand, and various obstacles arose in designing Raspberry Pi.

Lomas said, “In 2009 we wanted to redesign around another processor. But due to the inability to proceed, everyone became demoralized.”

“There were too many components, the PCB was too large, power consumption was excessive, and all sorts of problems arose.”

Despite this, Lomas said everyone was unwilling to break away from the $35 price point.

He said, “When we first announced the price, everyone thought we were crazy. We once thought we were crazy too, but our motivation was that if we could achieve it, it would attract a lot of kids.”

Meanwhile, Upton had to juggle his full-time job at Broadcom, complete his MBA studies, and tackle the Raspberry Pi project.

He said, “Before 2011, it often seemed like this thing would never happen just because I was too busy. I had other things to do; this wasn’t my top priority.”

By early 2011, progress was still slow, but an opportunity presented itself to Upton and Lomas: their employer Broadcom had designed a low-cost chip that was perfect to serve as the foundation for an affordable computer.

Upton and Lomas used a processor typically found in electrical equipment and digital signage and then used it as a platform for a low-cost computer.

This new chip promised to support a computer comparable to high-end machines from the late 1990s—roughly equivalent to a 300MHz Intel Pentium 2. Of course, that wasn’t the kind of performance that excited anyone, but it was enough to provide a usable machine for under $35.

The key was that this ARM-based Broadcom BCM2835 system-on-chip would make Raspberry Pi more than just a toy or a stripped-down electronic product.

Upton said, “This was a big breakthrough; we had the ARM processor, ARM 11.”

Since it ran a full Linux-based operating system, Raspberry Pi could boot into a windowed desktop, which typical users would see as a computer.

Lomas said, “You have a complete operating system, and you can incorporate all the free software development tools that have been available in the Linux environment for years.”

Lomas said this gave them a sense of victory, “The chip made by Broadcom had many features that were exactly what we needed.” Upton and Lomas’s Raspberry Pi now had the necessary “big chips” (like memory and network controllers) as platform guarantees, and more importantly, the prices were all affordable. However, the battle was not over; their insistence on low prices would still put immense pressure on the foundation.

Upton said, “The basis for pricing between $25 and $35 was the price points of those large components, and then thinking, ‘The rest can’t be too expensive.’ Of course, that thinking was wrong.”

“One of our big lessons is that it’s the small things that will kill you, not the big ones. A lot of things that cost around 10 cents, rather than a few dollars, will inflate the cost of the device.”

▴Raspberry Pi Alpha version board, first produced in 2011. Image: Raspberry Pi Foundation

To make matters worse, Upton and Lomas quickly added pressure on themselves. The BBC’s coverage of the thumb-sized prototype of Raspberry Pi went viral in May 2011—reporting that Raspberry Pi would be launched within a year.

Upton said, “The report very firmly presented our image to the public; we had no way out but to try to make it a reality.”

“So, during the summer and fall of 2011, Pete and I were together, trying to find ways to drive down the cost of the product. For example, we considered which features could be discarded, identifying cheaper means to achieve certain features, etc.”

The foundation faced a tough battle. The founders had already loaned the foundation hundreds of thousands of dollars, enough to increase Raspberry Pi’s production from the initial 3,000 to about 10,000 boards. However, that was still a relatively low volume in electronics manufacturing, which would lead to rising component costs.

By August, the foundation had a reference design for Raspberry Pi, and Broadcom produced 50 Alpha boards for them. These boards were very different from the thumb-sized prototype shown in May, supporting many of the features later found in Raspberry Pi—such as several USB 2.0 ports, a 100M Ethernet interface, a microSD card reader, HDMI, and booting into the Linux Debian command line. It could even play a bit of the first-person design game “Quake III.” The problem was that it was still far from the low cost they needed and was slightly larger than the credit card size they wanted.

Lomas said, “The next question was how to turn this $110 monster into a $35 practical solution.” He and Upton spent from August to December figuring out how to do that.

Turning the $110 monster into Raspberry Pi was a battle.

Every component of the little board had its place; Lomas recalls facing extremely difficult choices when weighing the relative merits of each component.

For example, they encountered the issue of how to connect Raspberry Pi to a display. They wanted Raspberry Pi to be good enough to work with newer TVs and monitors, which generally required HDMI connections, but they also wanted it to work with older CRT monitors, which required VGA connections, and even older televisions that required composite video connections. Ultimately, Lomas said VGA consumed too many serial interface pins on the chip, which would reduce the number of other features that could be supported, so they opted for HDMI and composite video connections.

Lomas said, “We worked hard. We actually sacrificed several things. We rationalized the I/O, removing unnecessary items. Then we reorganized and went back to basics. They nicknamed me ‘the executioner’.”

The battle raged on every part. Each component had to be delicately balanced on cost, quality, and usability.

Upton said, “Achieving points 1 and 2 is relatively easy, but achieving all three is extremely difficult, which led to many such arguments.”

In some cases, Upton and Lomas employed clever avoidance tactics to push costs down. A dedicated audio chip in the original design was replaced with six registers and capacitors and software that generated audio via pulse-width modulation. Elsewhere, they would first lower specification requirements and then consider improving certain defects in later boards, such as initially choosing a linear power supply, which Upton considered “very inefficient,” but would later be replaced with “Rolls-Royce level switch-mode power supply designs.”

Not everything was cut back. At Lomas’s request, the number of pins (general-purpose input/output ports) on later boards increased from 26 to 40, enabling the computer to control lights, switches, motors, and interact with other boards. Although this feature was added later, Lomas said it was “a significant part of Raspberry Pi” because it facilitated the birth of many Raspberry Pi-driven robots. Upton agreed, “Today, if you ask those applicants at Cambridge University, ‘How did you come to study computing?’ they will say, ‘Raspberry Pi and robots.’”

By this stage, Upton’s workload had reached 80 hours a week, working on Raspberry Pi whenever he could, whether at night, on weekends, on planes, or trains. He recalls one time he was even on the phone with Lomas while boarding at Heathrow Airport, “Asking him to send me the BOM (Bill of Materials) so I could work on the plane,” which made some passengers around him nervous. (Editor’s note: perhaps the pronunciation of BOM sounded like a bomb.)

During their collaborative efforts, there were no other team members or sufficient infrastructure to support Upton and Lomas—only a few volunteers came to help at their homes.

Lomas said, “We started with just six people, no office, only a few phones, and everything we did was through email and Google. But everyone was highly motivated to make it happen.”

By December, the design of Raspberry Pi finally reached the desired state. A week before Christmas, Lomas made 20 internal test boards at Norcott Technologies in Cheshire.

That evening, just three days before Christmas, Lomas recalls powering on the first board that came off the line and received an unpleasant surprise.

He said, “When we powered on the first board on the bench, our hearts were in our throats, but the board did nothing.”

“Later, we found out we had misread part of the documentation. The documentation had indeed been reviewed, but no one noticed.”

Fortunately, the problem was relatively simple to fix with some manual soldering—just a broken voltage rail.

On the same evening, when Upton arrived at the factory, Lomas was still fixing the last test board. After six months of continuous work, Upton and his wife, Liz, the foundation’s media director, had just returned from a vacation in Cornwall.

Upton said, “By the time we got to Cheshire, it was late.”

“I plugged one of the boards in; it was a strange experience because this was a machine I knew could be made for $25, but it was so much more powerful than any machine I had as a child, even more powerful than my beloved Amiga.”

This beta version board was the first generation Raspberry Pi, Pi 1 Model B (officially launched on February 29, 2012). Upton and Lomas reduced the functionality of this $35 board to two USB ports, a 100Mbps Ethernet, HDMI 1.3, 26 GPIO pins, and a 700MHz single-core processor with a VideoCore IV GPU capable of hardware-accelerated playback of 100p video. To uphold the foundation’s educational mission and commitment to transparency, each board was provided with various Linux-based operating systems and a set of programming tools.

Handling Success

However, the foundation now faced a new problem—it had become a victim of its own success. Upton and the board’s co-creators initially didn’t consider Pi too much, thinking the number sold would not exceed 1,000. Even when Pi’s public debut garnered 600,000 views on YouTube within two days, the team behind the board remained cautious.

He said, “Despite seeing the high interest, we still thought the actual number of people willing to spend money would be much lower,” explaining why the foundation only slightly increased the initial production to 10,000.

But the rocket-like demand growth did not diminish, and the foundation’s production capacity seemed inadequate; by February 29, when Raspberry Pi officially went on sale, orders had already reached 100,000.

The foundation’s manufacturing model was batch processing, with production volumes of 10,000 at a time; the revenue from one batch was used to fund the next batch, a speed that could not meet the demand growth.

Supply chain considerations, along with sales tax and manufacturing costs, complicated matters further, forcing the foundation to move production to China.

Upton and his colleagues realized the foundation needed to change its approach.

Upton said, “We discovered there was massive demand for the product, so much so that our available funds couldn’t meet it.”

“So we switched to a licensing model, licensing the design to RS Components and Premier Farnell.”

▴Eben Upton at the Sony factory in South Wales, the production site for Raspberry Pi.

Under this deal, Farnell and RS Components were responsible for the production and distribution of Raspberry Pi boards, subcontracting the manufacturing to a third party—initially to a factory in China, but since the end of 2012, it has been transferred to a Sony factory in South Wales.

Looking back, Upton believes this licensing model was a key decision that helped Raspberry Pi achieve its current success—it greatly expanded the production scale of Raspberry Pi and leveraged those companies’ global distribution networks.

He said, “I still feel most proud of that change because it released the value of this thing. It’s what allowed us to grow.”

In early March, with 100,000 orders accumulated, massive online hype, and new capabilities to manufacture boards in bulk, Upton says he began to realize the scale of Raspberry Pi’s appeal.

He recalls the scene when he received the first batch of Raspberry Pi boards for sale.

“I remember picking up one of the Raspberry Pi boards from the top of a stack of 50 boxes.”

“I took one board from the top box, ran to (foundation founder) Jack Lang’s living room, connected it to his TV, and it worked. We pulled one from the bottom and randomly pulled one from the middle to ensure they hadn’t put a working one on top. We plugged it in again, and it powered up successfully, and at that moment we thought, ‘Wow, this thing is going to be a hit. Maybe we can sell 500,000 units.’”

▴The first batch of Raspberry Pi 1 Model B produced in China

Since the launch of the Raspberry Pi 1 in 2012, this momentum has shown no signs of slowing down. In 2017, over 22 million Raspberry Pi boards were sold globally, and three generations have been released so far, the most recent being the Raspberry Pi 3 Model A+, which has seen significant upgrades compared to the machine launched in 2012 for $25. This success has funded a broad educational expansion initiative, which, through coding clubs, has taught over 150,000 children a week of programming knowledge, and through the foundation’s online projects, over 8.5 million people have been educated.

The foundation, which started with six people, has now grown into an international organization with offices in the UK and the US, and they have even set up a branch, Raspberry Pi Trading, to handle engineering and trading activities. Even someone who tinkered with Raspberry Pi as a child has now joined their hardware team.

For Upton, the evidence of Raspberry Pi’s success lies not only in the millions of boards sold but also in its ability to give a new generation the same thrill he felt when he wrote games on the BBC Micro.

He said, “You can even see those kids lying on the living room floor, watching pictures of Raspberry Pi on TV, just like we did back then.”

Years later, those kids are entering university, and the number of applicants for computer science at Cambridge University is starting to climb again.

“We now have numbers back up to 1,000—you’re starting to see everything change.”

Upton continually emphasizes that Raspberry Pi is not a creation of one person; it has always been a collective product of a group of experts in software, hardware, marketing, case design, etc. This is even more true today.

He said, “We like to tell the narrative of Steve Jobs and Woz. But when you develop something as complex as Raspberry Pi, the story doesn’t go that way.”

One example illustrates the point. That is how the foundation built up this huge Raspberry Pi community. These people often help each other and share their projects. This strong sense of community was largely facilitated by Liz Upton (now the foundation’s media director), who transitioned from a freelance journalist to a full-time volunteer for the foundation in 2011, and Eben said she “invented many of the techniques we still use to engage with the community.”

Looking back, while Upton feels proud of the foundation’s achievement in launching Raspberry Pi 1 in 2012, he says that the Raspberry Pi 1 Model B+ in 2014 was what they intended to create.

He said, “If you look at the Pi 1 B+, you’ll see that’s what we hoped to make in 2012, but we had to make sacrifices.”

“After that, we were able to add more GPIO, the form factor became more reasonable, USB ports increased, and energy efficiency improved.”

The success of this computer made it possible to realize the original vision of Raspberry Pi. In the second year after this computer’s launch, tech enthusiasts purchased over 2.5 million Raspberry Pis, and the previous challenge of low board numbers disappeared.

The next version to be launched will be Raspberry Pi 4, but Upton expects this one to differ significantly from the previous ones and require a migration to an entirely new system-on-chip to support faster and more efficient processors. This will be the biggest challenge since Raspberry Pi 2, and Upton says their ambitious plan is to launch this board within the 2020-2021 window.

Single-board computers are not worth much today, and you can’t demand much from small devices that impersonate Raspberry Pi—whether it’s Banana Pi, Orange Pi, or Strawberry Pi. But what would the world be like if Raspberry Pi hadn’t been created?

Upton said, “That’s an intriguing question—but no one knows the answer, right?”

He speculated that perhaps Arduino would have extended from making microcontroller boards to producing low-cost SBCs, or BeagleBoards SBCs would have dropped to Raspberry Pi’s price. Maybe he and the Raspberry Pi creators were just lucky.

“Perhaps it was just a timely idea that happened to be ripe, and we just happened to step in.”

Upton said, from some perspectives, the birth of Raspberry Pi required a certain degree of naivety. If he and his colleagues had been more aware of the challenges they faced at the outset, they might never have embarked on this endeavor.

He said, “You know, I think we were just too naive.”

“On one side, there’s knowing so little that you’re not prepared for bold things; on the other side, there’s knowing enough to bring a team together. There’s a delicate line between the two.”

“To some extent, ignorance was a blessing for us. We didn’t know what was impossible, so we accomplished something impossible.”

Original link: https://www.techrepublic.com/article/inside-the-raspberry-pi-the-story-of-the-35-computer-that-changed-the-world/

• Article content sourced from 36Kr compilation team, edited by: 36Kr Hao Pengcheng, Cover photo: Gear Pear Amnesia Battery, copyright belongs to the original author. If there is any infringement, please contact us to delete. Welcome to reprint and share, please respect the original source.

More exciting content from Gear Pear

Click the text to view

· What is the biggest problem in Chinese education?

· This is a school that subverts your perception

· Worth billions, prefers to be called teacher

· Why did this rough game attract over 70% of students?

· In an age full of returnees, STEM has become the key to studying abroad in the US

· This organization won Tencent’s annual award for upgrading education with technological innovation

· What makes the education of the country with the largest innovation investment in the world so excellent?

· Actually, our children can have more opportunities

· Li Kaifu: I will make everything in the classroom disappear

· The Segway Gear Pear Innovation Laboratory was established

Click Read the original article to view the latest education news and innovative courses