Solid-state haptic technology enables new forms of human-machine interaction while providing safety benefits, cost savings, and multi-sensory brand differentiation.

Consumers now live in two worlds—the physical and the digital. They want their cars to understand this dual reality and operate seamlessly like their smartphones and other smart devices. This preference for connectivity is one of the key factors driving significant changes in the underlying technologies of automotive interiors, touchscreens, and connected driving experiences.

Trends in Automotive Connectivity and Displays

The industry is moving towards more connected, ultimately software-defined vehicles where links to the cloud and other wireless destinations are standard across the industry. According to predictions cited in SBD Automotive’s “2030 Experience Report,” built-in vehicle connectivity is expected to surge from 48% of all new cars globally in 2020 to nearly 96% by 2030.

To meet the connectivity demands of drivers and passengers, the sizes of new automotive displays are continually increasing (15 inches and above, even extending between pillars) while also becoming thinner. Step into any modern vehicle, and you may see multiple screens, along with curved displays along the center console and other areas inside.

This 56-inch curved glass dashboard exclusive to the 2022 EQS extends seamlessly from door to door, integrating three screens. (Source: Mercedes-Benz)

According to McKinsey & Company, by 2030, these touchscreens will either be fully integrated into existing interior surfaces or foldable and retractable, making them less obtrusive. Automakers are experimenting with new designs and placements for driver and passenger screens to showcase interactive interfaces in new ways, preparing consumers for a future where electrification, sharing, and autonomous vehicles redefine mobility as we know it today.

However, despite numerous innovations in size, shape, placement, and connectivity, the topic of automotive touchscreens often remains polarizing. When the in-car life experience of drivers and passengers does not match the ease and familiarity of interacting with everyday digital devices, connectivity is just one reason they feel frustrated. Some drivers complain about losing familiar physical controls and having to learn new digital interfaces. Other sources of resistance can be seen in headlines from automotive magazines discussing road safety and driver distraction associated with visually-based displays. Mazda even decided to eliminate touchscreens based on their research showing that drivers inadvertently apply torque to the steering wheel when reaching for the touchscreen, leading to lane position drift.

While audio, chatbots, and AI virtual assistants can certainly make technology easier to use, the various applications, colorful icons, and gestures used in smartphones today primarily rely on visual means for operation. Given the popularity and success of smartphone interfaces, it is not surprising to see many of the same approaches and visual languages transferred to vehicle display design. This brings us to a second question—perhaps a more direct one—safety.

Minimizing Driver Distraction

For many drivers, adjusting the radio volume simply requires reaching out to feel a physical dial or the steering wheel, allowing them to lower the volume without taking their eyes off the road. But in the process of navigating smooth, featureless displays and visually-based controls, we lose the familiar physical feel of controls. The elimination or replacement of buttons creates a void of tactile feedback that previously provided tactile and eyes-free control.

If human-machine interfaces (HMIs) require additional hand-eye coordination to locate and operate controls, then the driver’s task becomes more complex. The use of visually-layered menu infotainment systems increases the cognitive load on drivers, which may also raise risks.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 436,096 people died in motor vehicle collisions on U.S. roads in 2019, a 2% decrease from 2018. However, the number of fatalities from crash incidents influenced by distraction increased by 9.9% during the same period. Audio cues can certainly help here, especially when they perform as expected. But the lack of standardization and the pace of technological change often lead to inconsistent and less-than-ideal driver experiences.

From Buzz to Surface Textures

When most people think of haptic technology, they might picture the buzz of their smartphone or the rumble of a gaming console. This sense of vibration is produced by physically moving mass using different types of motors (e.g., eccentric rotating mass (ERM) or linear resonant actuators (LRA) vibration motors). Every form of vibration haptics on the market today can be traced back to vibrating motors. Until a new branch of haptic technology—surface haptics—was invented.

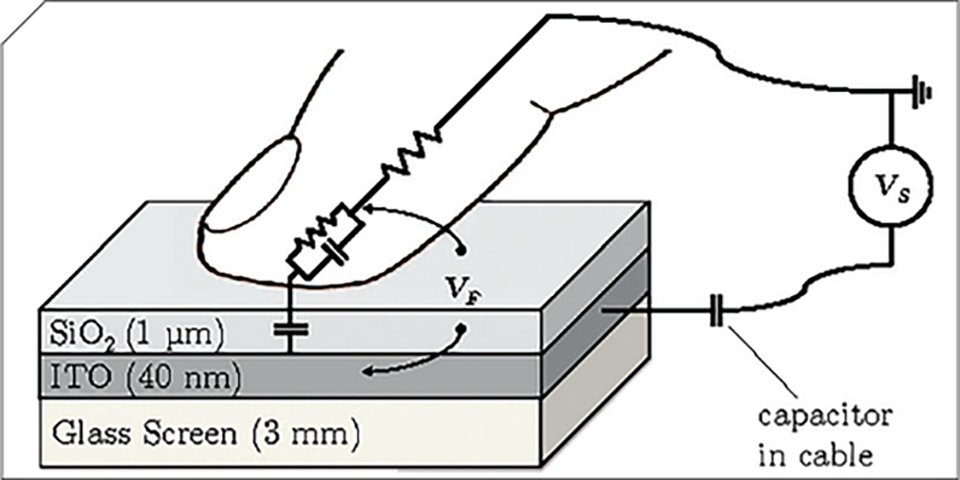

Surface haptics are programmable tactile textures and effects on physical surfaces. Instead of traditional vibrating actuators, surface haptics work through a phenomenon known as electroadhesion (Figure 2). By generating an electric field on the touchscreen surface, the friction felt by the finger as it moves across the screen can be altered.

Electroadhesion diagram: The electric field acts on the skin surface, producing an additional normal force that increases adhesion. V, applied voltage; F, electrostatic force.

As the finger moves across this friction, programmable software can create sensations of bumps, ridges, and textures—feelings that people are accustomed to experiencing on physical objects. Surface haptics are experienced by directly exploring the surface with the finger, so if the finger is not in motion, the sensation of touch controls cannot be felt.

Conceptually and practically, electroadhesion-based surface haptic technology differs from traditional vibration haptic technology in the following ways:

-

How it is built: No piezoelectric, motors, or other moving parts; this solution is completely solid-state.

-

How it is programmed: Software-defined, high-resolution effects can be designed in localized areas.

-

How it is experienced: Effects can be felt as the finger glides across the surface.

Key Considerations for Automotive Haptics

Automakers need to consider several key areas when specifying and designing haptics for vehicle interiors. Safety issues can be addressed by designing control systems that drivers can locate and operate with a quick glance or without taking their eyes off the road. A study from Northwestern University using a full vehicle driving simulator showed that adding surface haptics increased the time eyes stayed on the road by 30%. Designers should also strive to minimize the number of menus needed to access controls, as this increases cognitive load.

In terms of cost, there are many short- and long-term factors to examine, including the number of moving parts, weight, and the impact of using vibration-based haptics. As in-vehicle screens grow larger, the physics become more challenging, making it difficult to move mass to create vibration-based haptics. In some cases, vibrating large mass objects without affecting the haptic effect and isolating them from other parts of the vehicle is no longer practical or cost-effective. For curved, flexible, and rollable screens, vibration may not even be an option.

Solid-state surface haptic solutions eliminate much of the cost and complexity associated with vibration. Because surface haptic technology does not cause the screen to vibrate, they avoid large actuators and mechanical mounts, allowing for scaling to larger screens. Additionally, the haptic experience is not affected by any additional vibrations generated by vehicle motion.

For automakers, it is also important to consider how haptic technology will fit into existing supply chains and weigh the related costs of different solutions. For example, a typical automotive switch group may have expenses beyond the module itself (e.g., expensive wiring components, labor), and there may be reliability issues due to air gaps, mechanical failures, moisture, and leaks.

Some automakers are replacing traditional switch groups with a single smart surface that can be reused across multiple automotive platforms and option packages (Figure 3). Adding haptic feedback to window control positions or front and rear controls can give drivers or passengers the confidence that their initiated actions have occurred. Software programmability also means that a single hardware design can be reused, updated, and upgraded in the field, allowing for new features to be added after purchase or at the dealership. These over-the-air (OTA) updates are a high-value investment in addressing cost, design, and customer experience issues.

Smart surfaces, like these digital door controls from Yanfeng, are appearing in many modern interior designs (Source: Yanfeng Global Automotive Interiors)

To achieve long-term energy savings, automakers must also consider which specific haptic technologies to adopt, where to place haptic effects (now and in the future), what surfaces this technology can support, and whether this technology needs to work in coordination across multiple surfaces of the vehicle. Integration considerations must also include how this technology integrates with audio, force sensing, and other complementary technologies.

Finally, when specifying haptic technology, it is important to consider the quality and range of possible haptic effects. Infotainment systems offer automakers a tremendous opportunity for brand differentiation. Those OEMs that understand the details of haptic technology, how it is programmed, and customer preferences will be best positioned to compete in the rapidly evolving connected future.

More Sliding, Less Clicking, and Multiple Areas

The way we interact with the digital world is continually evolving. When you want to feel something in real life, you rarely walk over and poke it. The natural tendency is to pick it up or slide your finger over it to assess its texture or feel. Surface haptics allow system designers to leverage this natural approach.

Today, the behavior of touching digital controllers is primarily regulated visually. We look at the screen to determine where to click and confirm the effectiveness of the action. In this case, there is a brief contact between the finger and the surface, so the opportunities for haptic feedback are limited, aside from the occasional buzz.

Unlike discrete clicks, sliding or swipe controls are primarily achieved through touch using dynamic motion. This continuous contact with the surface provides opportunities to present haptics throughout the motion. By adding textures and motion, more surface effects become possible. Sliding and gesture-based interactions have become increasingly common in smartphones and tablets, making the learning curve faster and more intuitive, even in unfamiliar environments.

Due to the nature of how vibration-based haptics move mass, the range of haptic effects is often limited to one person across the entire screen. The solid-state properties of surface haptic technology allow designers greater freedom to create different effects and experiences in different areas of the same piece of glass—allowing multiple users to have unique experiences.

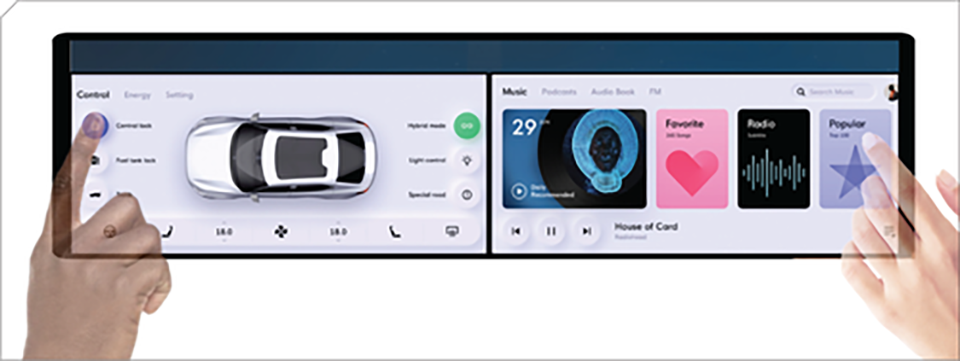

For example, when activating multi-area haptics with surface haptics, the digital surface is divided into two or more areas. Both the driver and passenger can operate and experience different haptic effects simultaneously on the same smart surface. For instance, as shown in Figure 4, the driver may choose to lock the doors while the passenger searches for music. Each person experiences different haptic feedback simultaneously on the same screen.

With multi-area haptic functionality, a single screen can be divided into two areas—one for the driver and another for the passenger (Source: Ran Mingwei, Car UI Concept, Behance, provided by Tanvas, Inc.)

Generating High-Resolution Haptic Effects

The ability to create dynamic haptic effects on large surfaces means a new level of haptic interaction is possible. For automotive manufacturers and HMI designers creating the next generation of human-machine interfaces, methods for creating haptic effects must also be evaluated.

Traditional vibration-based haptic solutions can produce a range of effects, but these effects may be limited. Generating effects involves complex motor controls and mechanical adjustments, as the entire surface is moving, and this effect can be felt anywhere on the device simultaneously.

Electroadhesion-based surface haptics allow for a wider range of textures since effects are only experienced when the finger moves on the surface and where it moves. Software programmability can not only speed up the haptic generation process but also enable novel high-resolution effects. Clicks on digital dials, flips of toggle switches, and any texture range from coarse to fine can be intentionally designed.

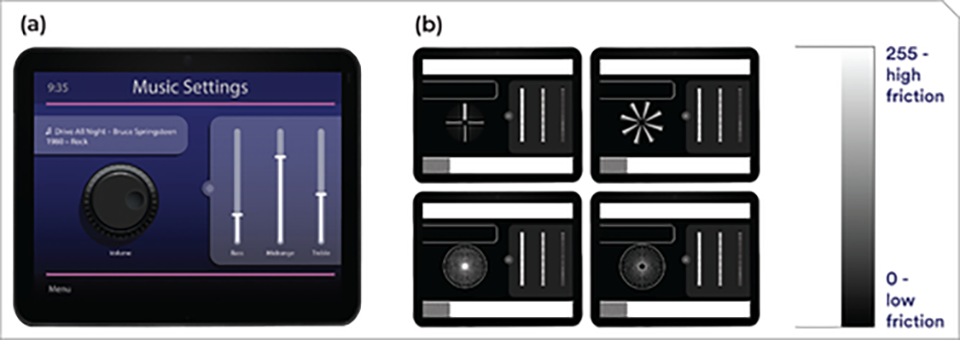

Surface haptic effects use grayscale bitmap images for programming, where the intensity of the haptic effect ranges from zero (none, darkest) to 255 (full, brightest), varying in intensity along the spectrum (between each grayscale). Using a simple image metaphor to decide where to place haptic effects and how they feel offers many benefits. Textures, stop lines, ridges, virtual scales, and edges can all be programmed using software and simple image-based metaphors (Figure 5). These features and effects are infinitely flexible and can be moved to any part of the display at any time or entirely replaced with different visual and haptic representations; they are not fixed like electromechanical haptics. Visual effects of OTA can also be updated, even after the system is sold to customers in the field.

Programming display surface haptic effects. (a) Graphic images are sent to the display and viewed by the driver or passenger. These visual effects can easily be updated using standard graphic or programming software. (b) These four images represent examples of corresponding haptic images created using the same software as the visible graphic images. Changing the underlying haptic texture of a volume knob alters the feeling of the finger moving across the display surface (Source: Tanvas, Inc.)

Unlike the waveform control used in vibration-based haptics, surface haptic assets are images that are easy to understand and operate in familiar ways; no special knowledge or tools are needed. Creating haptic images matches pixel-for-pixel with graphic images, providing high-resolution effects that can change in real-time with graphics and vary based on the speed and direction of finger movement.

In the automotive space, this high pixel-level resolution provides HMI designers with a broad range of options for creating new sensory experiences. Coupled with audio, these controls can begin to mimic realistic experiences while allowing automakers to flexibly adjust their appearance and feel as trends change and connected products evolve.

The Art and Science of Designing Haptic Interfaces

User interface design is a blend of art and science, encompassing all interactions between drivers or passengers and the automotive interface. Designers must consider the layout of various controls, the overall look and feel of the design, and even the response time of selection and completion actions. Textures can be designed and rendered on the screen, and graphic objects can be massive, heavy, or elastic. The only limits are the designer’s imagination and mastery of the tools.

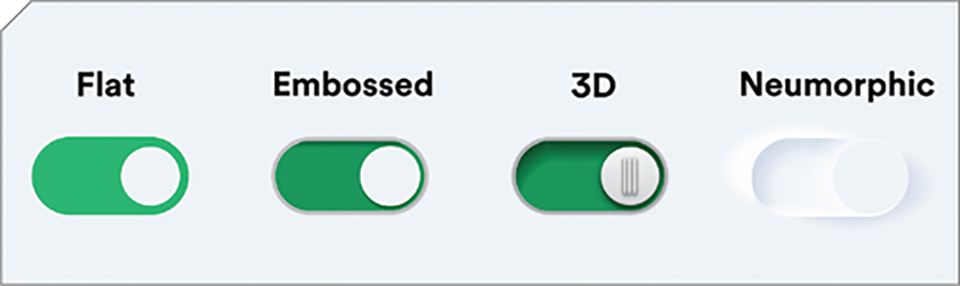

As HMI technology continues to evolve, visual design standards are also evolving. Over the years, preferences for graphic styles have changed. For example, in the early 2010s, as many internet giants rebranded their familiar icons, flat icons became popular. Flat icons follow a “less is more” approach, simply conveying information or promoting products, while embossed and 3D images use more gradients and shadows to add depth to the icons, often making them appear more realistic (Figure 6).

Various graphic styles used in digital applications and interfaces (Source: Tanvas, Inc.)

According to the Interaction Design Foundation, skeuomorphism refers to the way interface objects mimic real-world objects in appearance or in the way users interact with them. To simplify the visual interface of smartphones, user experience designers have shifted from skeuomorphic icons to flat designs.

Neumorphism is a new skeuomorphic style that focuses not necessarily on the contrast or similarity between the real and digital worlds, but rather on the color palette. In neumorphism, the emphasis is on how light moves in three-dimensional space; sometimes these effects are referred to as “soft design,” with various tools helping to create them.

As HMI technology advances, these design trends will continue to evolve. Electroadhesion-based haptics with graphical (visual) and haptic (textural) depth can shift design back to more realistic controls. Combining haptic and visual effects can also shorten the learning curve and adoption of new technologies.

The Future of Cabin Design and the Role of Haptic Technology

Given all the latest concept vehicles on display, there is no doubt that automakers will continue to innovate. In a highly interconnected automotive future, understanding where to focus efforts may be the decisive factor between winners and losers.

McKinsey’s research indicates that OEMs and suppliers need to focus on several strategic imperatives for interior differentiation. At the top is establishing a wealth of new knowledge regarding HMI technology, OTA, and future materials, then reducing complexity to optimize costs and make customers’ lives easier. Haptic technology can play a leading role in these efforts.

As creativity and design freedom shift to the HMI layer, automakers can explore haptic technology as an innovative feature that sets their interiors apart in this transformative mobility era while providing future-facing technologies to support the upcoming demands of connectivity, autonomous driving, sharing, and electrification. In the context of broader strategic guidelines for the widespread implementation of haptic technology, OEMs and suppliers must keep the following requirements in mind:

-

Intuitive and easy to discover;

-

Low latency;

-

Harmonious;

-

Size, shape, and material;

-

Noise-free;

-

No moving parts;

-

High bandwidth and resolution;

-

Integrated cost and ease of use.

Current automotive trends require a comprehensive assessment of the fundamental aspects of vehicles. Automotive interiors provide a playground for designers’ imaginations that has yet to be fully explored. Automotive and HMI designers are the artisans of the future, deciding where to place smart surfaces and controls, and how they should work and feel. The ability to create high-resolution haptics with pixel-point precision may open a new creative chapter in automotive history.

If you want to learn more about cars, feel free to call or message us on WeChat!

Source: Kevin Klein

Hotline:010-56281131

Some images in the article are sourced from the internet; please contact us for removal if there is any infringement.

– Service Content –

Long press to follow the mini program for more exciting content.