Author: Nick Heath

Translator: Wuming

Editor: Xiaozhi

From 2018 to 2019, the popularity of all programming languages declined, except for Python. Why has Python become increasingly popular? This article outlines the history of Python’s development and attempts to reveal the secrets behind its success.

At the end of 1994, a group of programmers from across the United States gathered to discuss their new secret weapon.

This was the first-ever Python workshop, attended by over 20 developers, including Barry Warsaw. He recalls the excitement of those early Python users:

“I remember someone saying, ‘Don’t tell anyone I came to this workshop because using Python feels like having a competitive advantage.’ To them, Python was their secret weapon, wasn’t it?”

At the early Python workshops, Warsaw mentioned that Python offered something that made coding simpler and easier to accomplish programming tasks.

He recalled, “When I first encountered Python, I knew it was something special. Python’s readability was good, and writing Python code became a joy.”

Today, enthusiasm for Python has far exceeded the initial developer circle. Some predict that with the rapid growth of the Python user base, it will soon become the most popular programming language in the world. Millions of people use Python every day, with the user base showing exponential growth and almost no signs of decline.

Whether professional or amateur developers, they are using Python to handle tasks big and small, especially web developers, data scientists, and system administrators. The first images of black holes released this year were stitched together using Python.

Python plays a key role in some world-renowned organizations, such as Netflix, which uses Python to deliver streaming video to over 100 million households globally, Instagram, which uses Python for photo sharing, and NASA, which uses Python to explore space.

The Early Years of Python

In some ways, Python’s rise is as unusual as the British comedy troupe (from which Python got its name). In its own domain, this programming language has also become increasingly famous and influential.

Python was originally a personal project of Dutch programmer Guido van Rossum. In the late 1980s, van Rossum developed distributed systems in the CWI department of the Netherlands National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science. Disappointed with existing programming languages, he decided to create a new language—one that was easy to use yet powerful.

Python’s Father Guido van Rossum

For an outsider, developing a programming language might seem like “building an airplane,” but at the time, the 30-something van Rossum was quite accomplished in some respects. He spent three years working with a team at CWI to develop ABC (an interpreted programming language), and he knew what it took to create an interpreter that could execute instructions and what syntax building blocks a new programming language needed.

For van Rossum at the time, accomplishing anything with the few programming languages available was quite difficult. The Amoeba distributed computing system he was developing required him to use C or Unix shell, both of which had significant limitations. C required developers to manage memory manually, which could lead to potential bugs, and it lacked reusable code libraries. Developers had to reinvent the wheel for every new project to accomplish everyday tasks. The Unix shell had another problem—it provided some utilities for everyday tasks, but they were too slow to handle complex logic.

The limitations imposed by these languages were so significant that van Rossum felt that creating his own interpreted language—borrowing some features from ABC—seemed like the best option.

van Rossum recalled, “I thought, why not create my own language? I could borrow some ideas from ABC and scale down the project, shortening what would take three years to complete into three months, making it my own personal project. Thus, Python was born.”

At the end of 1989, van Rossum began seriously developing the language and named it after his favorite comedy troupe, “Monty Python,” and later adopted the logo of a coiled python due to its association with snakes.

He said, “At that time, my social life was not rich. I either watched TV or wrote code, sometimes doing both at the same time.”

Although van Rossum nominally developed Python to better accomplish everyday work, he admitted that his motivation was more driven by the challenge of creating a language.

He said, “At that time, I didn’t know if Python would really make my work more efficient. To some extent, I really enjoyed the idea of completing a large project on my own and being able to design and implement it the way I wanted. To me, programming was fun.”

For the average person, developing a programming language might seem unusual, but examples like van Rossum are not unique. In the late 1980s, the emergence of various major programming languages was due to the limited tools available that could not meet developers’ needs. Larry Wall once said that he created Perl because other languages struggled to solve his problems, and he was a “lazy, impatient, and arrogant” person. Similarly, John Ousterhout designed Tcl to find a language suitable for building integrated circuit interaction tools.

Three months later, van Rossum produced a working prototype of Python.

He said, “Although modern Python has many abstract features that did not exist at the time, the language itself has remained consistent.”

“At that time, Python already had the basic components needed to parse and run the language. The first runnable Python programs can still run today.” Their function definitions are the same, the indentation is the same, the syntax for creating dictionaries and tuples is the same, and the interactive prompt is the same.

When his two colleagues began using the language to handle everyday tasks, van Rossum did not expect it to become popular. He knew how difficult it was to make a programming language popular before the internet age.

Today, sharing software with the world takes just a few clicks, but in the 1980s, it was a laborious task. van Rossum recalled the difficulties he faced promoting ABC:

“I remember around 1985, I went to the United States for vacation for the first time. I had a suitcase full of tapes.”

At that time, the only available means of communication was email, which was not suitable for distributing source code. He obtained the addresses and phone numbers of people interested in ABC from emails and delivered tapes door-to-door. Despite his efforts to deliver tapes to users, he could not make ABC truly popular.

He said, “Although ABC offered many excellent features, we did not make much progress in promoting it.” However, with the evolution of the internet revolution, promoting Python became much easier; he no longer had to drag a suitcase full of tapes around.

In 1991, van Rossum released Python to the world through the alt.sources newsgroup. At that time, it was essentially an open-source license, predating the term “open-source license” by six years. Although the Python interpreter at that time still required connecting 21 separate parts into a compressed file and needed to be downloaded overnight from the Usenet network, it was still much more efficient than the previous method of delivering tapes offline.

He said, “I hoped Python would succeed; after all, my previous project had basically ended in failure.”

van Rossum said that for a long time, he did not realize that Python’s user base was growing. Gradually, he became aware that the momentum for Python’s development was forming, and after communicating with the Python community for a while, he knew that Python had succeeded.

“This realization came very slowly. After releasing the first open-source version, I established a new release cycle and communicated frequently with the Python community. We felt it was a remarkable thing.”

Why Python is Winning

Python began to gain attention in the early to mid-1990s, marking the arrival of Python’s era, which surprised van Rossum.

van Rossum believes that the developers attracted to Python turned to it for the same reasons he created Python. They needed a high-level scripting language that could balance usability and functionality. They wanted to end the days of manually managing memory in C and having to reimplement code for repetitive tasks when starting new projects.

Warsaw said that Python strikes a balance between usability and functionality—something no mainstream programming language offered in the early 1990s. “I wrote a lot of Perl, Tcl, and C code, and they were not fun at all. When Python appeared, I thought, ‘Wow, it makes programming more enjoyable!’”

Whether in the past or present, Python offers clear and explicit syntax, using indentation to group code into blocks, making it easier for developers to read and understand the code.

Fintan Ryan, R&D Director at Gartner, said that whether now or in the 1990s, Python’s clear style played an important role in attracting developers, although there is some disagreement among developers about achieving this effect through indentation. “Python’s syntax is very concise. You can implement indentation in other languages, but Python has done it automatically. Some programmers like this indentation style, while others do not.”

In 1994, Barry Warsaw at the first Python workshop

Python emphasizes code simplicity and readability, which is not accidental. van Rossum has publicly stated that programming languages should not only tell computers what to do but also facilitate the communication of ideas among developers.

Ryan said that in addition to readability, Python had built-in some common functionalities early on, which made Python stand out from other languages. “You could use certain features from the start, such as classes and exception handling. Python also provided support for functions like lambda, map, and filter, which are very useful in many cases.”

If the mainstream programming languages of the late 1980s had been a bit better, perhaps Python would not have had the opportunity. One of van Rossum’s motivations for developing Python was that Perl was incompatible with the Amoeba distributed computing system he was using at CWI. He said, “Python was fortunate that Perl could not be ported to Amoeba. If Perl could have been ported to Amoeba, I would not have thought of creating a language myself.”

Although Python attracted a group of loyal fans after its release, it still lagged behind in the programming language landscape during the 1990s. van Rossum said that Python’s competitors were Tcl/Tk and Perl, both of which aimed for simplicity and power, just like Python.

He said, “In the 1990s, among the top three programming languages, Perl was undoubtedly first, Tcl/Tk was second, and Python was third.”

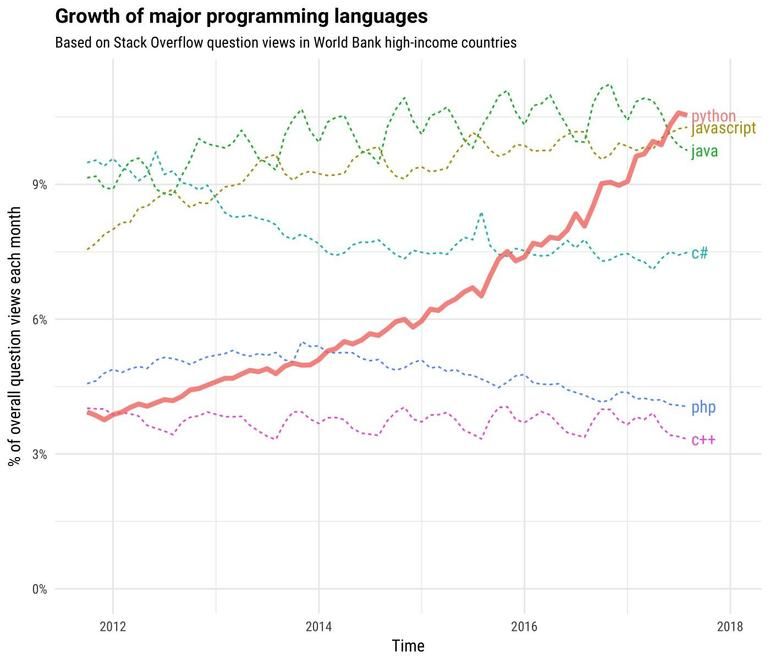

Stack Overflow’s developer report shows that in terms of developer activity, Python is the fastest-growing programming language, while Perl is shrinking, and it has even not appeared in the latest Stack Overflow developer report.

The following image shows this explosive growth. In recent years, the number of questions related to Python on Stack Overflow has grown far faster than other programming languages.

So how did Python surpass its former competitors? How can we explain the starkly different fates of these two languages? van Rossum believes it relates to the ease of maintaining codebases once they reach a certain scale. He said, “From people’s experience, Perl is suitable for writing scripts with fewer lines, but if your core code exceeds 500 lines, along with thousands of lines of branch code, maintaining that code in Perl requires following many principles. In Python, you don’t need to follow as many principles, and the code still maintains good readability and maintainability.”

Python is both simple to use and robust enough to develop large applications, and this combination is the reason for Python’s success in the 1990s.

“Some internet developers wanted to create increasingly large applications, and they realized that developing applications in Python was much easier than in C, C++, or Java.”

As Python gradually gained popularity in the 1990s, van Rossum, still working at CWI, found that the programming language he created increasingly connected him with people from around the world.

Python and the Web

In the mid-1990s, Python found new applications, from audio recording and playback to its first foray into web development, which later became a major application area for Python.

van Rossum said, “Web development is important, and it is also something I find very interesting.” Python began to be used alongside Perl and shell scripts for web server backend development. “You can create dynamic web pages, which is one of my favorite applications of Python.”

Ryan from Gartner said that in the 1990s, Python became popular among developers mainly because it could be used to quickly create powerful scripts. “As a very powerful scripting language, it lowered the barrier to entry for many users.”

Ryan also said that the language is very flexible and easy to learn, attracting users with varying levels of technical expertise. He said, “System administrators use Python for system automation, while developers leverage Python’s functional programming features and class inheritance, which Perl is much weaker at. Python has a low barrier to entry, and once people become familiar with the language, their work quickly becomes efficient.”

In 1994, Python caught the attention of Michael McLay, who was then in a senior position at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) and is now at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). McLay was thinking about how to help scientists at the NBS benefit from Python’s ease of use. In van Rossum’s view, the scientists at the NBS “needed to handle large amounts of data, but they were not good at programming.”

To promote Python at the NBS, McLay invited van Rossum, who was still working at CWI in the Netherlands, to be a guest researcher at NIST for two months. This move became a catalyst for Python’s future development and marked an important turning point in van Rossum’s life.

van Rossum with Warsaw and Roger Masse at the first Python workshop

It was during this time that they held the first Python workshop in the NBS office. van Rossum, Barry Warsaw, and other early Python enthusiasts gathered to share what they were doing with Python and their expectations for its future development.

It was also in this office that van Rossum met Bob Kahn, the author of the TCP/IP protocol.

This meeting led to a job offer for van Rossum—to work with Kahn at the Corporation for National Research Initiatives (CNRI), a non-profit research organization in Virginia focused on strategic development and research in network technology.

Just as Python met people’s expectations for a new programming language, when he received this job offer, van Rossum was filled with anxiety about his future work at CWI.

He said, “CWI was more like an academic institution, and they put some ‘gentle’ pressure on me to either pursue a PhD or find work elsewhere.”

“At that time, I was 35 years old, and pursuing a PhD was not very appealing to me. The popularity of Python had opened up some new possibilities for me, but after some phone calls and reflection, I decided to pass on those opportunities. I preferred CNRI, liked the conditions they offered, and liked the project, so I went to CNRI.”

It was at CNRI that van Rossum, with the help of a group of Python enthusiasts, combined many structures used to manage the Python language. After joining CNRI in April 1995, van Rossum led a small development team to develop a program called Knowbot, a mobile agent running on distributed computer systems.

This team used Python as the development language, and people like Jeremy Hylton, Roger Masse, Barry Warsaw, Ken Manheimer, and Fred Drake joined in. These individuals later played important roles in the Python community.

van Rossum said, “We formed a team of 4 to 10 people, most of whom worked at CNRI. They were all core developers of the Python language.”

This team created the python.org website, set up a CVS server for managing codebase changes, and established the “Python Special Interest Group” mailing list for improving and maintaining the Python language.

Since Python’s public release in 1991, its user base has grown significantly. By the late 1990s, Python attracted a large number of users from around the world. During this period, with the formation of the predecessor of the Python Software Foundation (PSF, officially established in 2001), the management of the Python language began to become standardized. As the community developed, the biennial Python workshops gradually evolved into larger annual events, eventually becoming the PSF’s annual PyCon, which remains popular to this day.

By the 21st century, the Python user base had grown, and early Python users were concerned about what would happen to Python if van Rossum were to have an accident.

Regardless, van Rossum continued to play a core role in Python. He was the heart of Python, and this idea never faded; some referred to him as Python’s “Benevolent Dictator For Life” (BDFL). This semi-joking title persisted for many years.

van Rossum said, “For a long time, I bore the pressure and developed project management skills. I delegated many tasks to others, allowing them to do things their way.”

Ryan from Gartner said that having the creator of the language also serve as the language manager is not a new concept. He also cited examples of Perl’s author Larry Wall and Node’s author Ryan Dahl, but he noted that van Rossum’s fairness in managing Python is commendable.

He said, “People generally believe that van Rossum has struck a very good balance in project direction and overall management.”

In fact, the open nature of Python established by van Rossum (open discussions among core developers in the community) is a decisive factor in Python’s success.

The Evolution of Python

During this period, Python underwent significant development. In 2008, Python 3.0 was released, modernizing Python as a programming language. Recently, there have been significant changes in how Python is managed.

These changes occurred last year when van Rossum stepped down from his BDFL title due to disagreements over the introduction of assignment expressions in PEP572.

Although the introduction of assignment expressions was intended to write code more efficiently, van Rossum faced severe criticism from opponents online, with some claiming that the proposal would reduce code readability and maintainability.

van Rossum said that while he had become accustomed to debates surrounding new features, this time he felt personally attacked, and some even resorted to personal attacks, leading him to decide to resign.

He said, “Those who disagreed technically began to complain on social media that I was undermining Python’s decision-making process or that I had made a serious mistake. I felt very disappointed and felt I was being attacked from behind.”

“In the past, when deciding whether to make changes or improvements to Python, a group of core developers would discuss the pros and cons. They would reach a clear consensus, and if the outcome was unclear, I would think it over repeatedly in my mind before making a decision. On the PEP572 proposal, despite its controversy, I chose to say, ‘Yes, I want to do this,’ but people did not accept it.

“This was not a rebellion, but I felt I did not have enough trust from the core developer community.”

He believes that the change in the way Python’s controversies are handled is partly due to the increasing number of people using Python.

“The size of the Python community is growing, which may be one reason. Of course, reaching any form of consensus is difficult because no matter what decision you make, there will always be some dissenters.”

Python core developer Mariatta Wijaya

Earlier this year, core developers responsible for maintaining the CPython interpreter established a steering committee to oversee Python’s future development. Members include van Rossum, Warsaw, and other core developers Brett Cannon, Carol Willing, and Nick Coghlan.

Warsaw said that when a programming language’s user base grows at such a rapid pace, it is necessary to manage the language’s development in this way.

He said, “I think van Rossum really took on all the responsibilities himself.”

“25 years ago, when Python was still a niche programming language, the community was much smaller, and van Rossum could still handle it alone, but even then, his workload was significant. I think, considering his personal health and the community’s involvement, it would be better to distribute these burdens among five people.”

Warsaw said that after each new feature version of Python is released, there will be a steering committee election to prepare for the next generation of Python language leadership.

He said, “If Python is still thriving 25 years from now, it should not be van Rossum and me managing it.”

The establishment of the steering committee has also been welcomed by the Python core developer community. Core developer Mariatta Wijaya said that this move feels like a step in the right direction. She said, “For me, a steering committee is much better than having one person decide everything—that’s a huge responsibility and burden. This is a good sign; it means the community will have more input.”

The Future of Python

While Python continues to attract new users at an astonishing rate, some within the community also see challenges ahead. If Python wants to remain evergreen, it must continue to evolve.

At this year’s Python language summit, BeeWare co-founder Russell Keith-Magee said that if support for mobile and web platforms does not improve, Python will face a “survival crisis.”

He said, “The penetration of mobile phones and tablets into the market has reached levels that desktop and laptop computers have never achieved, but the entire community lacks a case for how to use Python on these devices. So, when laptops gradually become niche devices, what predicament will Python face?”

He pointed out some issues with Python, such as the lack of support for compiling code on non-x86 hardware platforms, the fragility of Python’s test suite on mobile and web platforms, the large size of Python applications, and the need to use the asyncio library when developing GUI code on Android, Windows, and web platforms, which requires extra work, as many modules in the standard library are incompatible with interpreters outside of CPython.

Warsaw said that Keith-Magee raised many good points and believes it is important for Python to keep pace with new platforms—mobile, tablets, and web technologies (like WebAssembly).

Warsaw said, “Currently, Python does not perform well in this regard,” and he hopes that iPhone or Android phones can also download applications developed using Python, and users may not even know “that they were developed using Python.”

The number of cores in modern processor chips is continuously increasing (Intel’s latest server processors have reached 48 cores), and Warsaw also hopes that Python can better allow tasks to run on multiple processor cores.

He is very interested in the work Eric Snow is doing on Python sub-interpreters. He said, “I hope to see more tasks being able to utilize multi-core processors.”

Snow is involved in a long-term project aimed at making it easier for Python to distribute tasks across multiple processor cores. He has revised the existing Python sub-interpreter and changed the interaction between the sub-interpreter and the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL).

Warsaw said, “These features will not appear in Python 3.8, but they may be included in 3.9. I think we will see these features in the next two to two and a half years. I am really glad that Eric can continue this work; it is very important.”

He said that there have been some failed projects in the past (like Gilectomy, aimed at allowing multi-threaded Python applications to run on multiple cores), but these projects taught us interesting lessons about how Python can better distribute workloads across multiple cores.

The Python community is modernizing the standard library. A proposal was recently released to remove outdated modules from the standard library. Python’s standard library is often considered one of Python’s strengths because it is used to handle many common tasks, which is why people say Python has “batteries included.” However, at this year’s Python language summit, someone raised the question: would it be better if people could choose modules from PyPI instead of using the built-in standard library?

Another question is whether the composition of the Python steering committee can better reflect the diversity of the Python user base in 2019.

Wijaya said, “I hope the steering committee can have better diversity, not just in terms of gender but also in terms of race and other aspects.”

“At the PyCon conference, I spoke with PyLadies members from India and Africa. They said, ‘When we hear people talk about Python or PyLadies, we think of North Americans or Canadians. But in reality, there are larger Python user bases in other countries; why not pay more attention to them?’ I think they made a good point. So, I hope to see this happen, and I think we all need to do our part.”

Warsaw said that despite having a “Benevolent Dictator” in charge, many ideas about Python’s development have come from the community in recent years.

He said, “These ideas really emerged from the community, rather than being imposed from the top down.”

Simple community projects can also have a huge impact on Python. For example, the type hinting feature, a feature of Python 3.5, was inspired by the mypy project initiated by a PhD student in 2012. Type hinting can perform optional type checking, helping developers discover certain types of bugs and preventing these bugs from permeating the program.

Link to mypy project:http://mypy-lang.org/

When a group of people simultaneously develops a large codebase, this extra layer of safety becomes very useful.

Warsaw said, “In my view, this allows Python to penetrate larger organizations (for example, Instagram is basically using Python 3).”

Additionally, asyncio is another example of the community driving Python’s development.

Link to asyncio:https://docs.python.org/3/library/asyncio.html

With the establishment of the steering committee and the unprecedented growth of the user base, van Rossum is optimistic that the “community-driven evolution of Python” will continue to achieve “unparalleled success.”

He said, “A community with a solid core of developers now has a new management system, and I think we are better prepared for the evolution of the Python language.”

Warsaw said that if anyone doubts whether the Python community has the ability to continue finding new applications for Python, they should look at the first image of a black hole captured using Python.

“There are always some people in the Python community whom I consider to be crazy Python scientists. They are always thinking, if we can do this today, can we go further tomorrow?”

Original link:

https://www.techrepublic.com/article/python-is-eating-the-world-how-one-developers-side-project-became-the-hottest-programming-language-on-the-planet/

Click to see fewer bugs👇