If Matlab is banned, it does not mean that open-source Python and Julia can be used freely, and even the ancestral C language may not be safe. Just like the new Arm technology being banned for Huawei does not mean that Huawei can freely use the so-called open-source RISC-V. The leaders of open-source technology are still in the United States, and the first major investor in commercializing RISC-V, which was incubated at the University of California, Berkeley, is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under the U.S. Department of Defense. As industry insiders say, the reasons for banning Chinese access to RISC-V are even more compelling than those for banning Arm.

Author: Wang Shuyi

Image: Internet

Recently, students from Harbin Institute of Technology and Harbin Engineering University reported on platforms like Zhihu that the student version of Matlab they previously purchased is no longer usable. When opened, a deactivation notification pops up, indicating that the previous authorization is invalid, and accounts under the Harbin Institute of Technology/Harbin Engineering University domain cannot access the website. A teacher responsible for Matlab technical support at Harbin Institute of Technology responded that since June 6, 2020, due to Harbin Institute of Technology being placed on the U.S. Commerce Department’s Entity List, the normal use of Matlab at the school has been affected, and they are currently in active communication with MathWorks in the U.S.

MathWorks responded that they just received the notification and, according to the latest export control list from the U.S. government, they can no longer provide services. Please pay attention to the school’s notifications for further updates.

Since the Trump administration took office, the U.S. has increasingly tightened export restrictions on China, attempting to exclude China from the global economic circle and disrupt the trend of technological globalization that has been in place since the collapse of the Soviet Union, with the semiconductor field being the first to be affected. Huawei has long been denied support for EDA tools and is not allowed to use Google Play and other Android services. After the further modification of control measures on May 15 of this year, there is a risk that Huawei’s production supply chain could be completely cut off.

If the U.S. controls semiconductor manufacturing equipment and EDA tool software, it is still limited to specialized markets. Banning a fundamental mathematical tool like Matlab extends control from specialized fields to general fields. Fortunately, the basic theories of mathematics and physics were established before World War II; otherwise, with the U.S.’s consistent technical control measures, we might have to return to a primitive state of agriculture and fire—though we might also get lucky and develop technology to a level unreachable by the Americans.

The U.S. has never been a proponent of free trade in international commerce. Since its founding, the U.S. has had the idea of export control. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, pointed out that “foreign supplies may be interrupted in political conflicts and wars. To avoid excessive dependence on foreign supplies, the U.S. should establish a domestic processing and production system through trade protection policies. It is also believed that exports of important raw materials and strategic materials should be restricted.”

At the First Continental Congress held in December 1774, it was declared illegal to import British goods. In the Continental Congress of 1775, it was also declared illegal to export goods to Great Britain, thus formally establishing the U.S. export control system. After that, the U.S. attempted to implement export control measures through various means, primarily through legislation. These laws mainly include embargo laws, trade laws with enemy countries, neutrality laws, and export control laws. Different stages in U.S. history show various export control measures implemented.

Before World War II, the U.S. did not have a legal system to regulate the export of important military products and technologies to potential enemies during peacetime. The U.S. government approved American companies to freely export any products and technologies to Germany, Italy, and Japan, which accelerated the growth of fascism and militarism and catalyzed the outbreak of World War II. After the outbreak of World War II, Congress began to consider whether to authorize the president to take necessary control measures on the export of important military materials and technologies.

In July 1940, Congress finally passed Public Law 703 to define this power of the U.S. president. This law authorized the president to prohibit or reduce the commercial export of military-related (military equipment, military goods) or any products, technologies, and services necessary for manufacturing (parts, machines, tools, materials) for the national interest of the U.S. In the execution process, the U.S. president only needs to issue a notice specifying the types of goods or technologies that are prohibited or reduced for export. This authorization is valid for two years.

With the end of World War II and the outbreak of the Cold War, the U.S. Congress officially enacted the first Export Control Act in February 1949. The content of this act shows that it institutionalized the export control procedures established by Public Law 703 passed in July 1940 and gave the president actual power, authorizing the president to impose embargoes or export restrictions for U.S. foreign policy, national security, and to help supply domestic shortages and curb inflation.

The purpose of this is to control the export of products and technologies with military applications to non-American ideological countries. Subsequently, the U.S. established a comprehensive export licensing system. Most government departments implemented export control policies. The U.S. export control policies towards the Soviet Union and other non-American ideological countries were not entirely consistent; these policies were formulated based on U.S. national interests and the development and changes in U.S.-Soviet, U.S.-China, and China-Soviet relations. However, in general, trade restrictions and technology controls were mainly initiated by the U.S.

From 1960 to 1979, the U.S. embargo list against China and the former Soviet Union included familiar items such as semiconductor components, CAD/CAM software, and the relatively older ADA language and assembly language.

Therefore, the ban on Matlab does not mean that open-source Python and Julia can be used freely, and even the ancestral C language may not be safe. Just like the new Arm technology being banned for Huawei does not mean that Huawei can freely use the so-called open-source RISC-V. The leaders of open-source technology are still in the United States, and the first major investor in commercializing RISC-V, which was incubated at the University of California, Berkeley, is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under the U.S. Department of Defense. As industry insiders say, the reasons for banning Chinese access to RISC-V are even more compelling than those for banning Arm.

In his article “How the U.S. Conducted Technological Containment During the Cold War,” Zhu Qichao pointed out that it is not difficult to see from the historical process that although the scope and intensity of U.S. export controls have changed over time, the restrictions on high-tech transfers have become increasingly stringent.

Shen Yi, in his article “Who Has a Stronger Ideological Orientation in China-U.S. Relations?” uses numerous cases to illustrate that our observation of China-U.S. relations must overcome a stereotype, namely that people usually think that the Chinese side has a strong nationalist tendency, especially the leaders of the Communist Party, whether early or modern leaders, have a strong ideological orientation. In contrast, the U.S. shows strategic flexibility, pragmatism, and foresight. In fact, in most cases, the opposite is true.

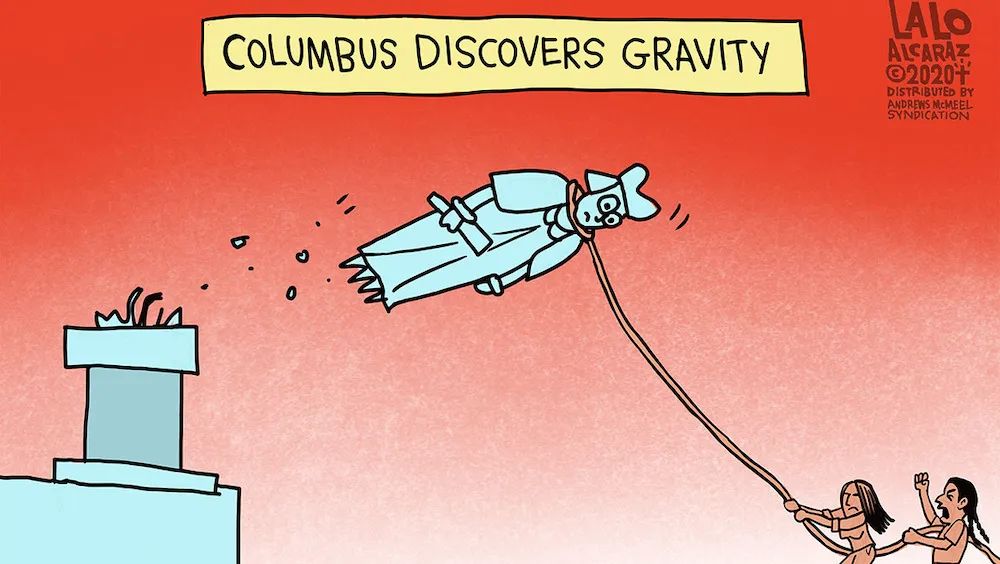

In 2020, Americans have increasingly walked down the path of ideological supremacy: due to alleged discriminatory remarks against Black people, the classic film “Gone with the Wind” was removed; because of disagreement with exempting Black students from exams, Gordon Klein from UCLA was suspended for three weeks; due to the commonly used terms “Blacklist” and “Slave” in code being deemed “politically incorrect,” American software developers called for establishing “politically correct code” to eliminate these terms from code…

Scott Hanselman, a programmer at Microsoft, has written a blog post about how to rename “master” (in contrast to slave) in programs to less offensive terms, while the Google Chrome team has requested developers to use “race-neutral” code, changing “blacklist” to “blocklist” in programs.

With Matlab banned—if Newton’s laws were “invented” and patented by Americans, they would probably be banned as well—we must seriously consider whether to build a non-American development toolchain from the ground up, from language to compiler and simulator, without relying on open-source software or fantasizing that we can use it freely once patents expire. Just like the RISC-V example, as long as it is American technology, there will always be ways to prohibit its use. After all, when Americans go crazy, even Columbus cannot stop them.

References:

“Computers and the Cold War—U.S. Export Restrictions on Computer Policies Towards China (1949-1979)” by Wu Min, May 2011

“How the U.S. Conducted Technological Containment During the Cold War” by Zhu Qichao, July 2019

“Who Has a Stronger Ideological Orientation in China-U.S. Relations?” by Shen Yi, May 2020

“American-style ‘Cultural Revolution'” by Yu Zai, June 2020

END