What is a filter?

Various sensor signals carry some noise signals to some extent. Filters can better reduce and eliminate noise, restoring the true useful signal.

A filter is a circuit that removes or “filters out” specific frequency components. In other words, it separates the frequency spectrum of the signal into frequency components that will pass through and those that will be blocked.

If you do not have much experience with frequency domain analysis, you may still be unsure what these frequency components are and how they coexist in a signal that cannot have multiple voltage values simultaneously. Let’s look at a brief example that helps clarify this concept.

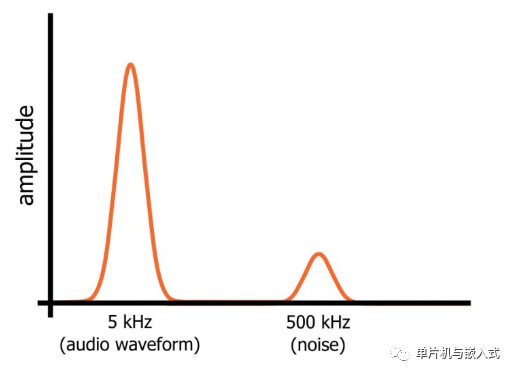

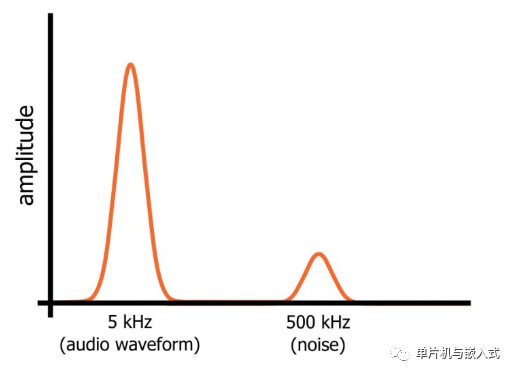

Assume we have an audio signal composed of a perfect 5kHz sine wave. We know what a sine wave looks like in the time domain, and in the frequency domain, we can only see a frequency “spike” at 5kHz. Now, let’s assume we activate a 500kHz oscillator, introducing high-frequency noise into the audio signal.

The signal seen on the oscilloscope is still just a sequence of voltages, each with a value at each moment, but the signal will look different because its time-domain variation must now reflect both the 5kHz sine wave and the high-frequency noise fluctuations.

However, in the frequency domain, the sine wave and noise are separate frequency components that coexist in one signal. The sine wave and noise occupy different parts of the signal’s frequency domain representation, which means we can filter out the noise by guiding the signal through a circuit that passes low frequencies while blocking high frequencies. The distribution of the different parts of the sine wave and noise signal in the frequency domain is illustrated below.

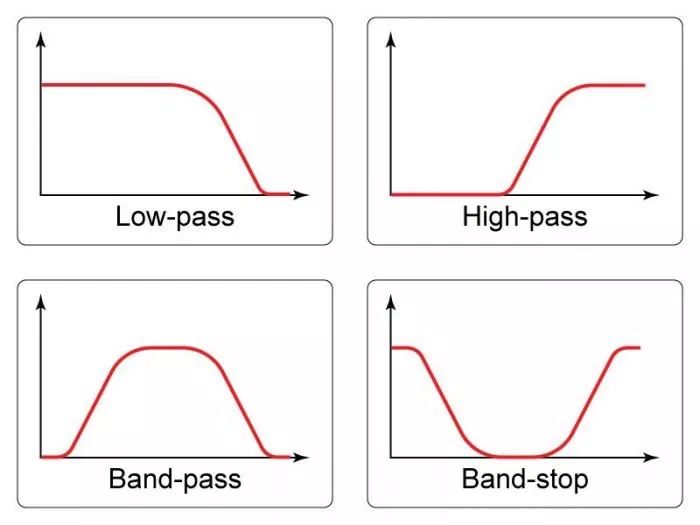

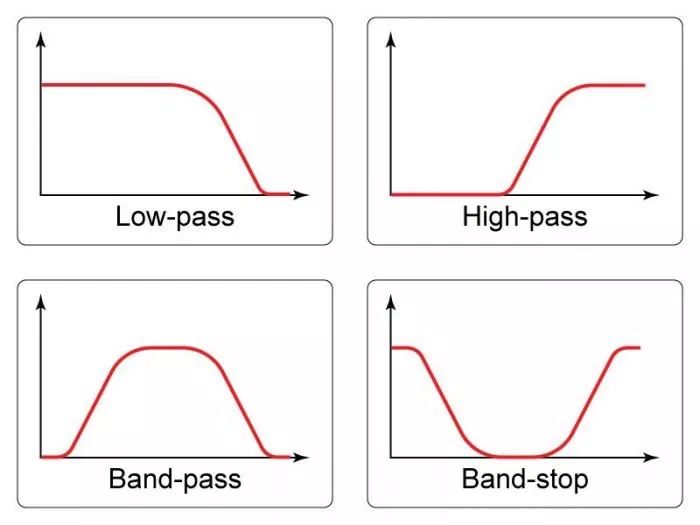

Filters can be broadly categorized according to the general characteristics of their frequency response. If a filter passes low frequencies and blocks high frequencies, it is called a low-pass filter; if it blocks low frequencies and passes high frequencies, it is a high-pass filter. There are also band-pass filters, which only pass a relatively narrow range of frequencies, and band-stop filters, which only block a relatively narrow range of frequencies. The frequency domain representations of various filters are shown in the diagram below.

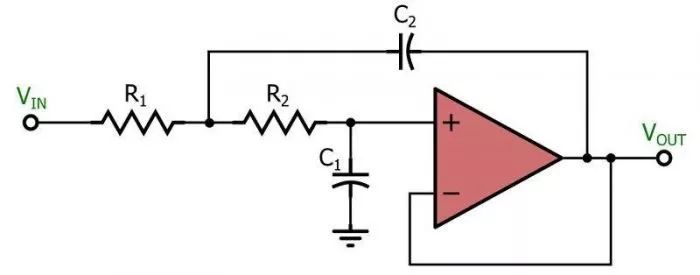

Filters can also be classified according to the type of components used to implement the circuit. Passive filters use resistors, capacitors, and inductors, which do not have the ability to provide amplification, so passive filters can only maintain or reduce the amplitude of the input signal. On the other hand, active filters can filter signals and apply gain because they include active components such as transistors or operational amplifiers, as shown in the diagram below.

This active low-pass filter is based on the popular Sallen-Key topology. For details, see this article: Sallen-Key Active Filter.

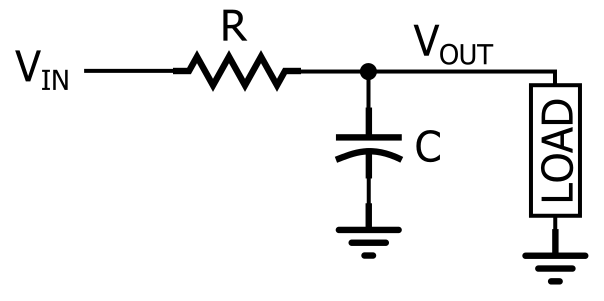

To create a passive low-pass filter, we need to combine resistive components with reactive components. In other words, we need a circuit composed of resistors and capacitors or inductors. Theoretically, the resistor-inductor (RL) low-pass topology is comparable to the resistor-capacitor (RC) low-pass topology in terms of filtering capability. However, in practice, the resistor-capacitor scheme is more common, so the remainder of this article will focus on the RC low-pass filter. The schematic of the RC low-pass filter is shown below.

As shown in the figure, an RC low-pass response can be produced by placing a resistor in series with the signal path and a capacitor in parallel with the load. In the diagram, the load is a single component, but in actual circuits, it may be more complex, such as the input stage of an analog-to-digital converter, amplifier, or oscilloscope used to measure the filter’s response.

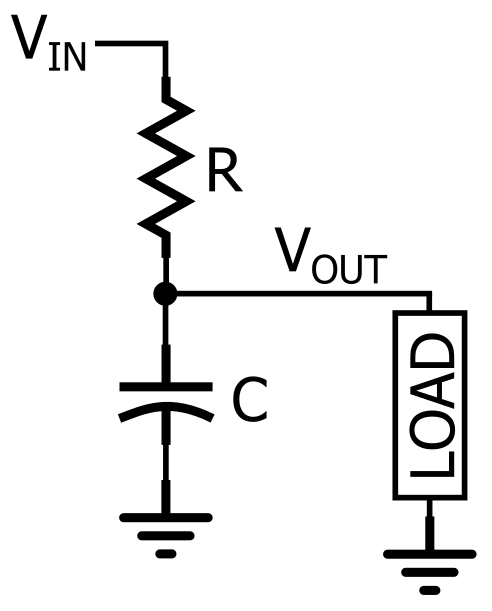

If we recognize that the resistor and capacitor form a voltage divider that is frequency-dependent, we can intuitively analyze the filtering action of the RC low-pass topology. Redrawing the RC low-pass filter to make it look like a voltage divider is shown in the diagram below.

When the frequency of the input signal is low, the impedance of the capacitor is high relative to the impedance of the resistor; thus, most of the input voltage drops across the capacitor (and across the load in parallel with the capacitor). When the input frequency is high, the impedance of the capacitor is low relative to the impedance of the resistor, which means the voltage across the resistor decreases, and less voltage is transferred to the load. Therefore, low frequencies pass through while high frequencies are blocked.

This qualitative explanation of the RC low-pass function is an important first step, but it is not very useful when we need to design a circuit practically since the terms “high frequency” and “low frequency” are very ambiguous. Engineers need to create circuits that pass and block specific frequencies. For example, in the audio system mentioned above, we want to retain the 5kHz signal while suppressing the 500kHz signal. This means we need a filter that transitions from passing to blocking between 5kHz and 500kHz.

RC Filter Cutoff Frequency

The frequency range where the filter does not cause significant attenuation is called the passband, while the frequency range where the filter does cause significant attenuation is called the stopband. Analog filters, such as RC low-pass filters, always transition gradually from the passband to the stopband. This means there is no single frequency that can be identified as the point where the filter stops passing signals and starts blocking signals. However, engineers need a convenient and concise way to summarize the frequency response of the filter, which is where the concept of cutoff frequency comes into play.

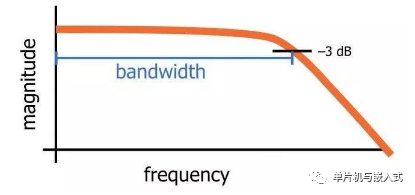

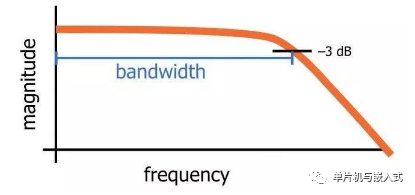

When you look at the frequency response graph of an RC filter, you will notice that the term “cutoff frequency” is not very accurate. The image of the signal spectrum being “cut” in half, where one half is retained and the other is discarded, is not applicable because the attenuation gradually increases as the frequency moves from below the cutoff point to above the cutoff value.

The cutoff frequency of an RC low-pass filter is actually the frequency at which the input signal’s amplitude is reduced by 3dB (the choice of this value is because a 3dB reduction in amplitude corresponds to a 50% reduction in power). Therefore, the cutoff frequency is also referred to as the -3dB frequency, and this name is actually more accurate and informative. The term bandwidth refers to the width of the filter’s passband; in the case of a low-pass filter, the bandwidth equals the -3dB frequency, as shown in the diagram below.

Filters can also be classified according to the type of components used to implement the circuit. Passive filters use resistors, capacitors, and inductors, which do not have the ability to provide amplification, so passive filters can only maintain or reduce the amplitude of the input signal. On the other hand, active filters can filter signals and apply gain because they include active components such as transistors or operational amplifiers, as shown in the diagram below.

This active low-pass filter is based on the popular Sallen-Key topology. For details, see this article: Sallen-Key Active Filter.

To create a passive low-pass filter, we need to combine resistive components with reactive components. In other words, we need a circuit composed of resistors and capacitors or inductors. Theoretically, the resistor-inductor (RL) low-pass topology is comparable to the resistor-capacitor (RC) low-pass topology in terms of filtering capability. However, in practice, the resistor-capacitor scheme is more common, so the remainder of this article will focus on the RC low-pass filter. The schematic of the RC low-pass filter is shown below.

As shown in the figure, an RC low-pass response can be produced by placing a resistor in series with the signal path and a capacitor in parallel with the load. In the diagram, the load is a single component, but in actual circuits, it may be more complex, such as the input stage of an analog-to-digital converter, amplifier, or oscilloscope used to measure the filter’s response.

If we recognize that the resistor and capacitor form a voltage divider that is frequency-dependent, we can intuitively analyze the filtering action of the RC low-pass topology. Redrawing the RC low-pass filter to make it look like a voltage divider is shown in the diagram below.

When the frequency of the input signal is low, the impedance of the capacitor is high relative to the impedance of the resistor; thus, most of the input voltage drops across the capacitor (and across the load in parallel with the capacitor). When the input frequency is high, the impedance of the capacitor is low relative to the impedance of the resistor, which means the voltage across the resistor decreases, and less voltage is transferred to the load. Therefore, low frequencies pass through while high frequencies are blocked.

This qualitative explanation of the RC low-pass function is an important first step, but it is not very useful when we need to design a circuit practically since the terms “high frequency” and “low frequency” are very ambiguous. Engineers need to create circuits that pass and block specific frequencies. For example, in the audio system mentioned above, we want to retain the 5kHz signal while suppressing the 500kHz signal. This means we need a filter that transitions from passing to blocking between 5kHz and 500kHz.

RC Filter Cutoff Frequency

The frequency range where the filter does not cause significant attenuation is called the passband, while the frequency range where the filter does cause significant attenuation is called the stopband. Analog filters, such as RC low-pass filters, always transition gradually from the passband to the stopband. This means there is no single frequency that can be identified as the point where the filter stops passing signals and starts blocking signals. However, engineers need a convenient and concise way to summarize the frequency response of the filter, which is where the concept of cutoff frequency comes into play.

When you look at the frequency response graph of an RC filter, you will notice that the term “cutoff frequency” is not very accurate. The image of the signal spectrum being “cut” in half, where one half is retained and the other is discarded, is not applicable because the attenuation gradually increases as the frequency moves from below the cutoff point to above the cutoff value.

The cutoff frequency of an RC low-pass filter is actually the frequency at which the input signal’s amplitude is reduced by 3dB (the choice of this value is because a 3dB reduction in amplitude corresponds to a 50% reduction in power). Therefore, the cutoff frequency is also referred to as the -3dB frequency, and this name is actually more accurate and informative. The term bandwidth refers to the width of the filter’s passband; in the case of a low-pass filter, the bandwidth equals the -3dB frequency, as shown in the diagram below.

The above figure represents the general characteristics of the frequency response of the RC low-pass filter, with bandwidth equal to the -3dB frequency.

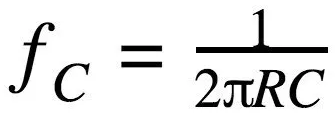

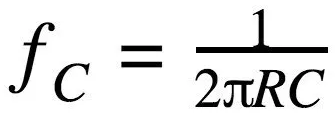

As mentioned above, the low-pass behavior of the RC filter is caused by the interaction between the frequency-independent impedance of the resistor and the frequency-dependent impedance of the capacitor. To determine the details of the frequency response of the filter, we need to mathematically analyze the relationship between resistance (R) and capacitance (C), and we can also manipulate these values to design filters that meet precise specifications. The cutoff frequency (fC) of an RC low-pass filter is calculated as follows:

Let’s look at a simple design example. Since the capacitance value is more restrictive than the resistance value, we will start with a common capacitance value (e.g., 10nF), and then we will use that formula to determine the required resistance value. The goal is to design a filter that will retain the 5kHz audio waveform and suppress the 500kHz noise waveform. We will try a cutoff frequency of 100kHz, which we will analyze more closely later in the article, as follows.

Thus, a 160Ω resistor combined with a 10nF capacitor will give us a filter that is very close to the desired frequency response.

Let’s look at a simple design example. Since the capacitance value is more restrictive than the resistance value, we will start with a common capacitance value (e.g., 10nF), and then we will use that formula to determine the required resistance value. The goal is to design a filter that will retain the 5kHz audio waveform and suppress the 500kHz noise waveform. We will try a cutoff frequency of 100kHz, which we will analyze more closely later in the article, as follows.

Thus, a 160Ω resistor combined with a 10nF capacitor will give us a filter that is very close to the desired frequency response.

Visualizing Filter Response

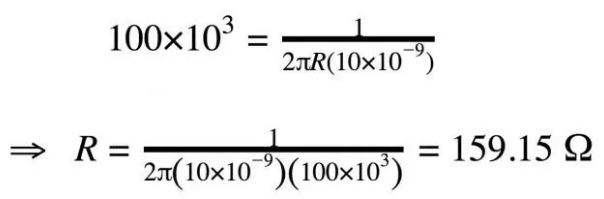

The most convenient way to assess the impact of the filter on the signal is to examine the graph of the filter’s frequency response. These graphs are often referred to as Bode plots, with amplitude (in decibels) on the vertical axis and frequency on the horizontal axis; the horizontal axis typically has a logarithmic scale, making the physical distance between 1Hz and 10Hz the same as that between 10Hz and 100Hz, and between 100Hz and 1kHz, and so on. This configuration allows us to quickly and accurately evaluate the behavior of the filter over a large frequency range. Below is an example of a frequency response graph.

Each point on the curve represents the amplitude that the output signal will have if the input signal has an amplitude of 1V and the frequency equals the corresponding value on the horizontal axis. For example, when the input frequency is 1MHz, the output amplitude (assuming an input amplitude of 1V) will be 0.1V (since -20dB corresponds to a tenfold reduction factor).

As you spend more time using filter circuits, the general shape of this frequency response curve will become very familiar. The curve in the passband is almost completely flat, and then as the input frequency approaches the cutoff frequency, it begins to drop off more steeply. Ultimately, the rate of change of the attenuation (known as the roll-off) stabilizes at 20dB/decade—that is, for every tenfold increase in input frequency, the amplitude of the output signal decreases by 20dB.

Each point on the curve represents the amplitude that the output signal will have if the input signal has an amplitude of 1V and the frequency equals the corresponding value on the horizontal axis. For example, when the input frequency is 1MHz, the output amplitude (assuming an input amplitude of 1V) will be 0.1V (since -20dB corresponds to a tenfold reduction factor).

As you spend more time using filter circuits, the general shape of this frequency response curve will become very familiar. The curve in the passband is almost completely flat, and then as the input frequency approaches the cutoff frequency, it begins to drop off more steeply. Ultimately, the rate of change of the attenuation (known as the roll-off) stabilizes at 20dB/decade—that is, for every tenfold increase in input frequency, the amplitude of the output signal decreases by 20dB.

Evaluating Low-Pass Filter Performance

If we carefully plot the frequency response of the filter we designed earlier in this article, we will see that the amplitude response at 5kHz is essentially 0dB (i.e., almost zero attenuation), and at 500kHz, the amplitude response is about -14dB (corresponding to a gain of 0.2). These values are consistent with the calculations we performed in the previous section.

Since RC filters always transition gradually from the passband to the stopband, and because the attenuation never reaches infinity, we cannot design a “perfect” filter—that is, one that has no effect on the sine wave and completely eliminates noise. Instead, we always need to make trade-offs. If we move the cutoff frequency closer to 5kHz, we will have more noise attenuation, but the sine wave we want to send to the speaker will also be attenuated more. If we move the cutoff frequency closer to 500kHz, the attenuation at the sine wave frequency will decrease, but the attenuation at the noise frequency will also decrease.

Earlier, we discussed how filters modify the amplitudes of various frequency components in a signal. However, in addition to amplitude effects, reactive circuit elements always introduce phase shifts.

Phase Shift of Low-Pass Filters

The concept of phase refers to the value of a periodic signal at a specific moment within its cycle. Therefore, when we say that a circuit introduces a phase shift, we mean that it creates a deviation between the input and output signals: the input and output signals no longer start and end their cycles at the same moment. The phase shift value (e.g., 45° or 90°) indicates the amount of deviation produced.

Each reactive element in the circuit introduces a 90° phase shift, but this phase shift does not occur simultaneously. The phase of the output signal gradually changes with the increase in input frequency, just like the amplitude of the output signal. In the RC low-pass filter, there is one reactive element (the capacitor), which means the circuit will ultimately introduce a 90° phase shift as well.

As with amplitude response, the phase response is most easily assessed by examining a curve that represents logarithmic frequency on the horizontal axis. The following description represents the general pattern, and the figure below can provide further details.

-

The phase shift starts at 0°

-

The phase shift gradually increases until it reaches 45° at the cutoff frequency, during which the rate of change gradually increases

-

After the cutoff frequency, the phase shift continues to increase, but the rate of change gradually decreases

-

As the phase shift approaches 90°, the rate of change becomes very small

The solid line represents the amplitude response, while the dashed line represents the phase response. The cutoff frequency is 100kHz. Note that the phase shift below the cutoff frequency is 45°.

Second-Order Low-Pass Filter

So far, we have assumed that the RC low-pass filter consists of one resistor and one capacitor. This configuration is a first-order filter.

The “order” of a passive filter is determined by the number of reactive elements (i.e., capacitors or inductors) in the circuit. Higher-order filters have more reactive elements, which produce more phase shift and steeper roll-off, and the latter is the primary motivation for increasing the order of the filter.

Adding one reactive element to the filter, such as moving from first-order to second-order or from second-order to third-order, can increase the maximum roll-off by 20dB/decade.

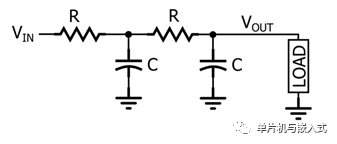

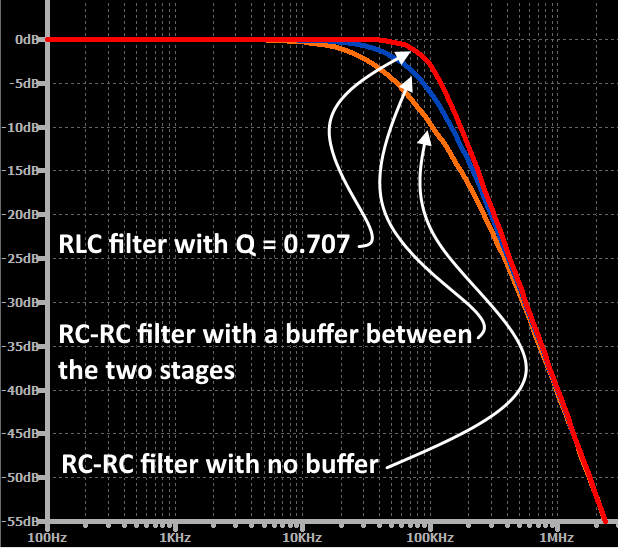

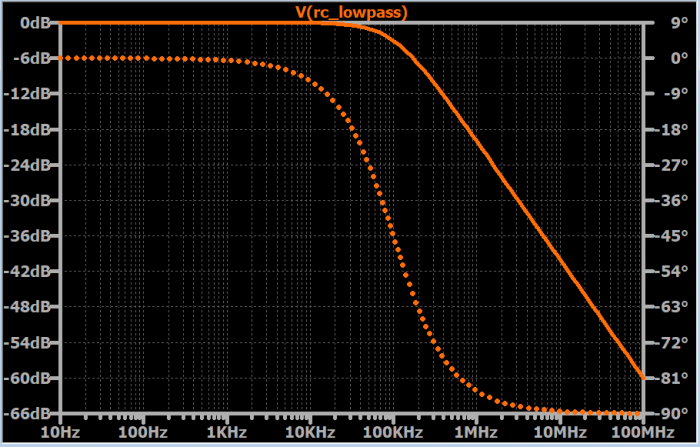

Second-order filters are typically built around a resonant circuit composed of inductors and capacitors, a topology known as RLC (Resistor-Inductor-Capacitor). However, second-order RC filters can also be created. As shown in the diagram below, all we need to do is cascade two first-order RC filters together.

While this topology will certainly produce a second-order response, it is not widely used, and its frequency response is usually not as good as that of second-order active filters or second-order RLC filters.

Frequency Response of the Second-Order RC Filter

We can try to design a first-order filter based on the desired cutoff frequency, and then choose two in series to create a second-order RC low-pass filter. This indeed can make the filter exhibit a similar overall frequency response, with a maximum roll-off of 40dB/decade instead of 20dB/decade.

However, if we look more closely at the response, we will find that the -3dB frequency appears to drop. The behavior of the second-order RC filter does not meet expectations because the two filter stages are not independent, and therefore cannot simply be connected together and analyzed as a first-order low-pass filter superimposed with another identical first-order low-pass filter.

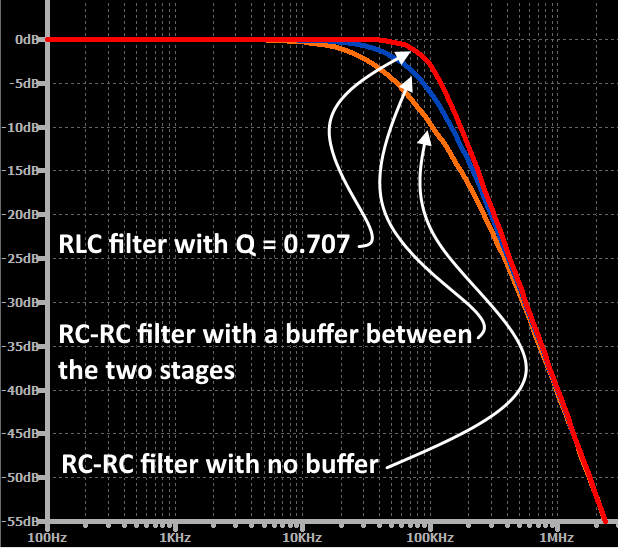

Moreover, even if we insert buffers between the two stages to make the first-order RC and second-order RC operate as independent filters, the attenuation at the original cutoff frequency will be 6dB instead of 3dB. This is precisely because the two stages work independently. The first filter has 3dB of attenuation at the cutoff frequency, and the second filter adds another 3dB of attenuation, as shown in the diagram below.

The fundamental limitation of the second-order RC low-pass filter is that the designer cannot fine-tune the transition from passband to stopband by adjusting the filter’s Q factor; this parameter indicates the damping level of the frequency response. If two identical RC low-pass filters are cascaded, the overall transfer function corresponds to a second-order response, but the Q factor is always 0.5. When Q=0.5, the filter is at the boundary of overdamping, which causes the frequency response to “droop” in the transition region. Second-order active filters and second-order resonant filters do not have this limitation; designers can control the Q factor, allowing them to fine-tune the frequency response in the transition region.

All electrical signals are a mix of desired frequency components and unwanted frequency components. Unwanted frequency components are usually caused by noise and interference, and in some cases, they can negatively affect the performance of the system.

Filters are circuits that respond differently to different parts of the signal spectrum. Low-pass filters are designed to allow low-frequency components to pass through while blocking high-frequency components.

The cutoff frequency of a low-pass filter indicates the frequency region where the filter transitions from low attenuation to significant attenuation. The output voltage of an RC low-pass filter can be calculated by viewing the circuit as a voltage divider composed of (frequency-independent) resistance and (frequency-dependent) reactance.

A curve showing amplitude (in dB on the vertical axis) against logarithmic frequency (in hertz on the horizontal axis) is a convenient and effective way to examine the theoretical behavior of the filter, and a graph showing the relationship between phase and logarithmic frequency can also be used to determine the amount of phase shift that will be applied to the input signal.

Second-order filters have steeper roll-off; this second-order response is useful when signals cannot provide wideband separation between desired frequency components and unwanted frequency components.

It is possible to create a second-order RC low-pass filter by building two identical first-order RC low-pass filters and then connecting the output of one to the input of the other, but ultimately the overall -3dB frequency will be lower than expected.

The fundamental limitation of the second-order RC low-pass filter is that the designer cannot fine-tune the transition from passband to stopband by adjusting the filter’s Q factor; this parameter indicates the damping level of the frequency response. If two identical RC low-pass filters are cascaded, the overall transfer function corresponds to a second-order response, but the Q factor is always 0.5. When Q=0.5, the filter is at the boundary of overdamping, which causes the frequency response to “droop” in the transition region. Second-order active filters and second-order resonant filters do not have this limitation; designers can control the Q factor, allowing them to fine-tune the frequency response in the transition region.

All electrical signals are a mix of desired frequency components and unwanted frequency components. Unwanted frequency components are usually caused by noise and interference, and in some cases, they can negatively affect the performance of the system.

Filters are circuits that respond differently to different parts of the signal spectrum. Low-pass filters are designed to allow low-frequency components to pass through while blocking high-frequency components.

The cutoff frequency of a low-pass filter indicates the frequency region where the filter transitions from low attenuation to significant attenuation. The output voltage of an RC low-pass filter can be calculated by viewing the circuit as a voltage divider composed of (frequency-independent) resistance and (frequency-dependent) reactance.

A curve showing amplitude (in dB on the vertical axis) against logarithmic frequency (in hertz on the horizontal axis) is a convenient and effective way to examine the theoretical behavior of the filter, and a graph showing the relationship between phase and logarithmic frequency can also be used to determine the amount of phase shift that will be applied to the input signal.

Second-order filters have steeper roll-off; this second-order response is useful when signals cannot provide wideband separation between desired frequency components and unwanted frequency components.

It is possible to create a second-order RC low-pass filter by building two identical first-order RC low-pass filters and then connecting the output of one to the input of the other, but ultimately the overall -3dB frequency will be lower than expected.

Source: STM32 Embedded Development

RF Industry-Academia-Research Technology Exchange Platform

Welcome to add the editor on WeChat as a friend Sharing valuable resources and the latest activities every day

Sharing valuable resources and the latest activities every day

Latest Conferences:

Online Lecture: Senior RF Product Manager Interprets Design Ideas and Performance Indicators of Domestic High-Performance RF Testing Instruments (March 30)

13,000-word detailed explanation of basic knowledge of RF microwave chip design (purely practical | RF system architecture and indicators, simulation extraction of component parameters, chip design environment construction) high-quality products | DC-67GHz, 10W, 30dB, 1.85mm coaxial fixed attenuator | Test curve (thin film process + elastic design + temperature shock test)

Heavyweight! Chip filter design practical guide “RF Microwave Chip Design” column is here! RFIC/MMIC designer salary, job requirements, development design process, and development tools

Sharing valuable resources and the latest activities every day

Sharing valuable resources and the latest activities every day