Author | Frontend Craftsman

Editor | Zhang Zhidong, Wang Wenjing

HTTP/2 has significantly improved web performance compared to HTTP/1.1, requiring only an upgrade to this protocol to reduce many of the performance optimizations that were previously necessary. Of course, compatibility issues and how to gracefully downgrade are likely among the reasons it is not yet widely used in China. Although HTTP/2 enhances web performance, it is not without its flaws, and HTTP/3 was introduced to address some of the issues present in HTTP/2.What changes have occurred since the invention of HTTP/1.1?

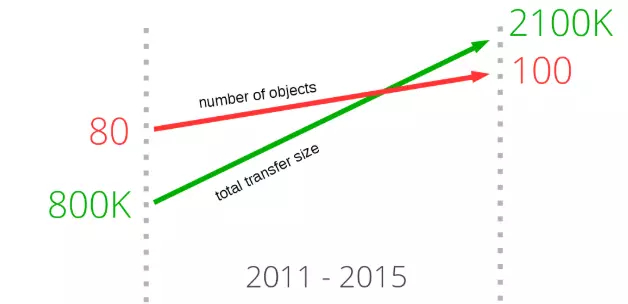

If you closely observe the resources that need to be downloaded to open the homepages of the most popular websites, you will notice a very obvious trend. In recent years, the amount of data required to load a website’s homepage has gradually increased, exceeding 2100K. However, what we should be more concerned about is that the average number of resources that need to be downloaded to complete the display and rendering of each page has surpassed 100.

As shown in the figure below, since 2011, the size of transmitted data and the average number of requested resources have continuously increased, showing no signs of slowing down. In the chart, the green line represents the growth of transmitted data size, while the red line represents the growth of the average number of requested resources.

Since the release of HTTP/1.1 in 1997, we have been using HTTP/1.x for quite a long time. However, with the explosive growth of the internet over the past decade, from primarily text-based web content to rich media (such as images, audio, and video), and with an increasing number of applications requiring real-time content (such as chat and live video), certain features defined by the protocol at that time can no longer meet the demands of modern networks.

Deficiencies of HTTP/1.1

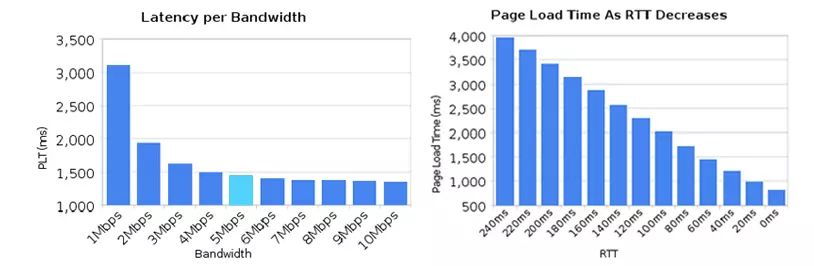

1. High Latency — Leading to Slower Page Load Speeds

Although network bandwidth has grown rapidly in recent years, we have not seen a corresponding decrease in network latency. The issue of network latency is primarily caused by Head-Of-Line Blocking, which prevents bandwidth from being fully utilized.

Head-of-line blocking refers to the situation where if one request in a sequence of requests sent in order is blocked for some reason, all subsequent requests in the queue are also blocked, causing the client to not receive data for a long time. To address head-of-line blocking, several approaches have been attempted:

- Distributing resources of the same page across different domain names to increase connection limits. Chrome has a mechanism that allows a maximum of 6 persistent TCP connections to be established for the same domain by default. When using persistent connections, although they can share a single TCP pipe, only one request can be processed at a time in that pipe. Other requests must remain blocked until the current request is completed. Additionally, if there are 10 requests occurring simultaneously under the same domain, 4 of those requests will enter a waiting state until the ongoing requests are completed.

- Sprite techniques combine multiple small images into a larger image, then use JavaScript or CSS to “cut” the small images out.

- Inlining is another technique to prevent sending many small image requests by embedding the original data of the images in the URL within the CSS file, reducing the number of network requests.

.icon1 {

background: url(data:image/png;base64,<data>) no-repeat;

}

.icon2 {

background: url(data:image/png;base64,<data>) no-repeat;

}- Concatenation combines multiple small JavaScript files into one larger JavaScript file using tools like webpack, but if one of those files changes, a large amount of data will need to be re-downloaded for multiple files.

2. Stateless Characteristics — Leading to Large HTTP Headers

Since message headers generally carry many fixed header fields such as “User Agent”, “Cookie”, “Accept”, “Server”, etc. (as shown in the figure below), they can amount to hundreds or even thousands of bytes, while the body often contains only a few dozen bytes (for example, GET requests, 204/301/304 responses), making it a true “big-headed son”. The large content carried in the header increases transmission costs to some extent. Even worse, many fields in thousands of request-response messages are repetitive, which is a significant waste.

3. Plaintext Transmission — Leading to Insecurity

HTTP/1.1 transmits all content in plaintext, and neither the client nor the server can verify each other’s identity, which to some extent compromises data security.

Have you heard of news stories about “free WiFi traps”? Hackers exploit the weaknesses of HTTP plaintext transmission by setting up a WiFi hotspot in public places to “phish” users, luring them to connect. Once you connect to this WiFi hotspot, all traffic will be intercepted and saved. If sensitive information such as bank card numbers or website passwords is included, it becomes dangerous, as hackers can impersonate you and do whatever they want.

4. Lack of Server Push Messaging Support

Introduction to the SPDY Protocol and HTTP/2

1. SPDY Protocol

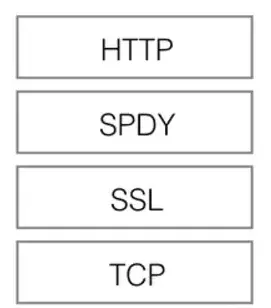

As mentioned above, due to the deficiencies of HTTP/1.x, we have introduced sprite images, inlined small images, and used multiple domain names to improve performance, but these optimizations circumvented the protocol. It wasn’t until 2009 that Google publicly released its self-developed SPDY protocol, primarily to address the inefficiencies of HTTP/1.1. The introduction of SPDY marked the formal modification of the HTTP protocol itself. Reducing latency, compressing headers, etc., the practical implementation of SPDY proved the effectiveness of these optimizations and ultimately led to the birth of HTTP/2.

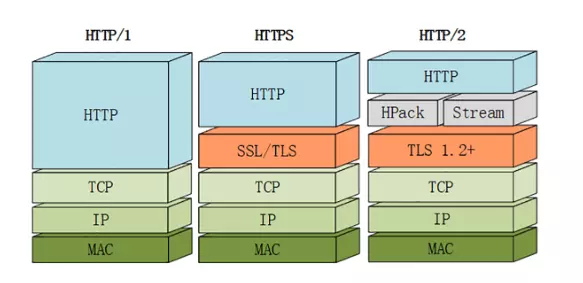

HTTP/1.1 has two main drawbacks: insufficient security and low performance. Due to the heavy historical burden of HTTP/1.x, modifying the protocol while ensuring compatibility is a primary consideration; otherwise, it would disrupt countless existing assets on the internet. As shown in the figure above, SPDY sits below HTTP and above TCP and SSL, allowing for easy compatibility with older versions of the HTTP protocol (encapsulating HTTP/1.x content into a new frame format) while utilizing existing SSL functionality.

After proving feasible in the Chrome browser, the SPDY protocol was adopted as the foundation for HTTP/2, inheriting most of its main features.

2. Introduction to HTTP/2

In 2015, HTTP/2 was released. HTTP/2 is a replacement for the current HTTP protocol (HTTP/1.x), but it is not a rewrite; the HTTP methods, status codes, and semantics remain the same as HTTP/1.x. HTTP/2 is based on SPDY, focusing on performance, with the primary goal of using a single connection between the user and the website. Currently, many top-ranking sites both domestically and internationally have implemented HTTP/2 deployment, which can bring a 20% to 60% efficiency improvement.

HTTP/2 consists of two specifications:

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol version 2 – RFC7540

-

HPACK – Header Compression for HTTP/2 – RFC7541

New Features of HTTP/2

1. Binary Transmission

The significant reduction in data transmission volume in HTTP/2 is mainly due to two reasons: binary transmission and header compression. First, let’s introduce binary transmission. HTTP/2 uses a binary format for data transmission, as opposed to the plaintext format of HTTP/1.x messages, making binary protocols more efficient to parse. HTTP/2 splits request and response data into smaller frames, and they are encoded in binary.

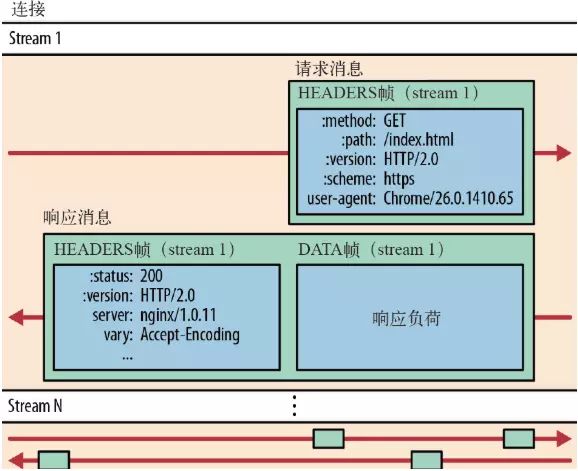

It moves some characteristics of the TCP protocol to the application layer, breaking the original “Header + Body” message into several smaller binary “frames” (Frame), using “HEADERS” frames to store header data and “DATA” frames to store entity data. After data framing in HTTP/2, the “Header + Body” message structure completely disappears; the protocol only sees individual “fragments”.

In HTTP/2, all communication under the same domain is completed over a single connection, which can carry any number of bidirectional data streams. Each data stream is sent in the form of messages, which consist of one or more frames. Multiple frames can be sent out of order, and can be reassembled based on the stream identifier in the frame header.

2. Header Compression

HTTP/2 does not use traditional compression algorithms but has developed a specialized “HPACK” algorithm that establishes a “dictionary” on both the client and server sides, using index numbers to represent repeated strings, and employs Huffman coding to compress integers and strings, achieving a compression rate of 50% to 90%.

Specifically:

- Both the client and server use a “header table” to track and store previously sent key-value pairs, so that the same data does not need to be sent with every request and response.

- The header table persists throughout the connection’s lifetime in HTTP/2, being progressively updated by both the client and server.

-

Each new header key-value pair is either appended to the end of the current table or replaces a previous value in the table.

For example, in the two requests shown in the figure below, the first request sends all header fields, while the second request only needs to send the differential data, thus reducing redundant data and lowering overhead.

3. Multiplexing

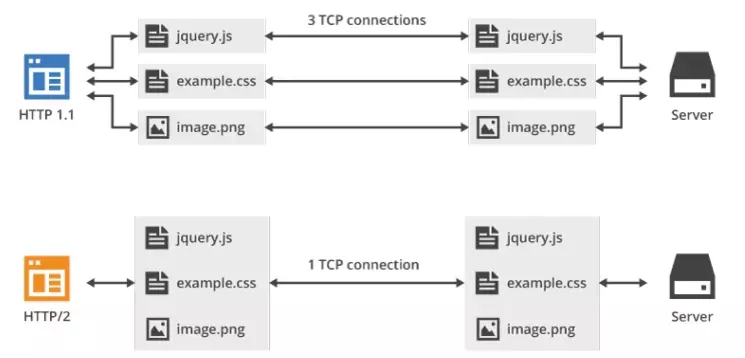

HTTP/2 introduces multiplexing technology, which effectively resolves the browser’s limitation on the number of requests under the same domain, while also making full-speed transmission easier, as establishing a new TCP connection requires gradually increasing transmission speed.

You can intuitively experience how much faster HTTP/2 is compared to HTTP/1 by visiting this link: https://http2.akamai.com/demo

In HTTP/2, with binary framing, HTTP/2 no longer relies on TCP connections to achieve parallel streams. In HTTP/2:

- All communication under the same domain is completed over a single connection.

- A single connection can carry any number of bidirectional data streams.

-

Data streams are sent in the form of messages, which consist of one or more frames, and multiple frames can be sent out of order, as they can be reassembled based on the stream identifier in the frame header.

This feature greatly enhances performance:

- Only one TCP connection is needed for the same domain, allowing multiple requests and responses to be sent in parallel over a single connection, thus the entire page resource download process only requires one slow start, while also avoiding the issues caused by multiple TCP connections competing for bandwidth.

- Multiple requests/responses can be sent in parallel and interleaved, without affecting each other.

-

In HTTP/2, each request can carry a 31-bit priority value, with 0 indicating the highest priority and larger values indicating lower priority. With this priority value, the client and server can adopt different strategies when processing different streams, sending streams, messages, and frames in the most optimal way.

As shown in the figure above, multiplexing technology can transmit all request data through a single TCP connection.

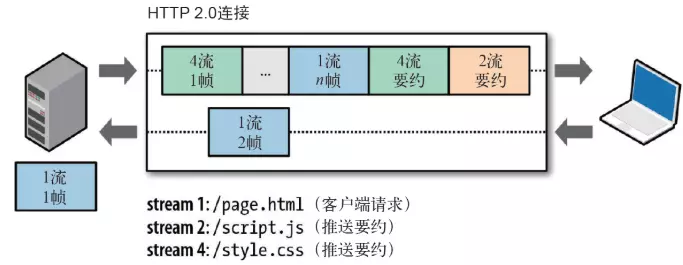

4. Server Push

HTTP/2 also changes the traditional “request-response” working model to some extent, as the server is no longer completely passive in responding to requests; it can also proactively send messages to the client by creating new “streams”. For example, when the browser requests HTML, it can proactively send the potentially needed JS and CSS files to the client, reducing waiting delays. This is known as “Server Push” (also called Cache Push).

As shown in the figure below, the server actively pushes JS and CSS files to the client without requiring the client to send these requests while parsing the HTML.

Additionally, it should be noted that while the server can proactively push, the client also has the right to choose whether to accept it. If the resources pushed by the server have already been cached by the browser, the browser can refuse to accept them by sending an RST_STREAM frame. Server push also adheres to the same-origin policy. In other words, the server cannot arbitrarily push third-party resources to the client; it must be mutually agreed upon by both parties.

5. Enhanced Security

For compatibility reasons, HTTP/2 retains the “plaintext” characteristic of HTTP/1, allowing for plaintext data transmission as before, without enforcing encrypted communication, although the format is still binary and does not require decryption.

However, since HTTPS has become the trend, and major browsers like Chrome and Firefox have publicly announced support only for encrypted HTTP/2, the “fact” is that HTTP/2 is encrypted. This means that the HTTP/2 commonly seen on the internet is typically running over TLS with the “https” protocol name. The HTTP/2 protocol defines two string identifiers: “h2” for encrypted HTTP/2 and “h2c” for plaintext HTTP/2.

New Features of HTTP/3

1. Drawbacks of HTTP/2

Although HTTP/2 resolves many issues present in older versions, it still has a significant problem, primarily caused by the underlying TCP protocol. The drawbacks of HTTP/2 mainly include the following points:

- Delays in establishing TCP and TCP+TLS connections

HTTP/2 uses the TCP protocol for transmission. If HTTPS is used, it also requires the TLS protocol for secure transmission, which involves a handshake process, resulting in two handshake delays:

① When establishing a TCP connection, a three-way handshake is required with the server to confirm the connection, meaning that data transmission cannot begin until 1.5 RTT has been consumed.

② For TLS connections, there are two versions—TLS1.2 and TLS1.3—each version takes different amounts of time to establish a connection, generally requiring 1 to 2 RTT.

In total, we need to spend 3 to 4 RTT before data can be transmitted.

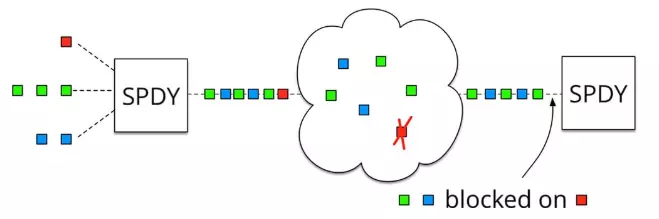

- Head-of-line blocking in TCP has not been completely resolved

As mentioned earlier, in HTTP/2, multiple requests run in a single TCP pipe. However, when packet loss occurs, HTTP/2 performs worse than HTTP/1. This is because TCP has a special “packet loss retransmission” mechanism to ensure reliable transmission; lost packets must wait for retransmission confirmation, causing all requests in that TCP connection to be blocked (as shown in the figure). In contrast, HTTP/1.1 can open multiple TCP connections, so if this situation occurs, it only affects one connection, while the remaining TCP connections can still transmit data normally.

At this point, some may wonder why not directly modify the TCP protocol? In fact, this is an impossible task. TCP has been around for too long, embedded in various devices, and this protocol is implemented by the operating system, making updates impractical.

2. Introduction to HTTP/3

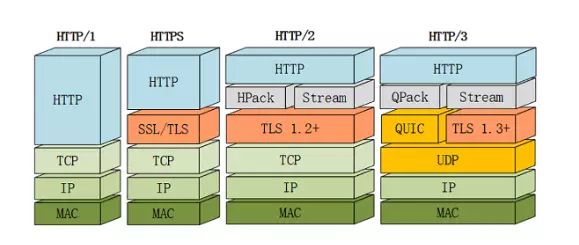

When Google was promoting SPDY, it had already recognized these issues, so it started from scratch to create a “QUIC” protocol based on UDP, allowing HTTP to run on QUIC instead of TCP. This “HTTP over QUIC” is the next major version of the HTTP protocol, HTTP/3. It achieves a qualitative leap over HTTP/2, perfectly solving the “head-of-line blocking” problem.

Although QUIC is based on UDP, it adds many features on top of the original, and we will focus on several new features of QUIC. However, HTTP/3 is still in the draft stage, and there may be changes before its official release, so this article will avoid discussing unstable details.

3. New Features of QUIC

As mentioned, QUIC is based on UDP, and since UDP is “connectionless”, there is no need for “handshakes” or “teardowns”, making it faster than TCP. Additionally, QUIC implements reliable transmission, ensuring that data reaches its destination. It also introduces features similar to HTTP/2, such as “streams” and “multiplexing”; a single “stream” is ordered and may be blocked due to packet loss, but other “streams” will not be affected. Specifically, the QUIC protocol has the following characteristics:

-

Implements features similar to TCP for flow control and transmission reliability.

Although UDP does not provide reliable transmission, QUIC adds a layer on top of UDP to ensure reliable data transmission. It offers packet retransmission, congestion control, and other features found in TCP.

- Implements fast handshake functionality.

Since QUIC is based on UDP, it can achieve connection establishment using 0-RTT or 1-RTT, meaning QUIC can send and receive data at the fastest speed, greatly improving the speed of the first page load. 0RTT connection establishment can be considered QUIC’s biggest performance advantage over HTTP2.

-

Integrates TLS encryption functionality.

Currently, QUIC uses TLS1.3, which has more advantages compared to earlier versions, the most important being the reduction in the number of RTTs required for handshakes.

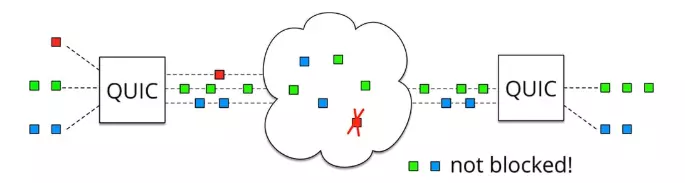

- Multiplexing, completely solving the head-of-line blocking problem in TCP.

Unlike TCP, QUIC allows multiple independent logical data streams over the same physical connection (as shown in the figure below). This enables separate transmission of data streams, effectively resolving the head-of-line blocking issue in TCP.

Summary

-

HTTP/1.1 has two main drawbacks: insufficient security and low performance.

- HTTP/2 is fully compatible with HTTP/1, being a “safer HTTP and faster HTTPS”; header compression, multiplexing, and other technologies can fully utilize bandwidth and reduce latency, significantly enhancing the web experience.

- QUIC, based on UDP, serves as the underlying support protocol for HTTP/3. This protocol, based on UDP, incorporates the essence of TCP, achieving a protocol that is both fast and reliable.