Hello everyone, welcome to <span>LiXin Embedded</span>.

In embedded development, structures are an indispensable tool. Compared to classes in object-oriented programming, C language structures are more like pure data collections without methods, making them simple and efficient. For embedded engineers, it is essential to not only use structures conveniently but also to understand their layout in memory; otherwise, one might easily fall into pitfalls. In this article, we will explore various usages and considerations of structures.

Basic Operations of Structures: Declaration and Usage

Structures are defined using the struct keyword, followed by the structure name and member list. Let’s look at a simple example:

struct sensor_data {

char id;

int value;

double timestamp;

char name[10];

};

This sensor_data structure serves as a template for sensor data, containing a character type sensor ID, an integer measurement value, a double precision timestamp, and an array that can store 9 characters plus a null terminator for the name. After declaring the structure, you can define variables to use it:

struct sensor_data s1;

s1.id = 'A';

s1.value = 100;

s1.timestamp = 1234.5678;

strcpy(s1.name, "TempSensor");

Members can be accessed directly using the dot operator, which is simple and intuitive. But what if you use pointers? Then you need to use the arrow operator:

struct sensor_data *sp = &s1;

sp->id = 'B';

sp->value = 200;

Here, it is important to note that the dot and arrow operators should not be confused; otherwise, the compiler will throw an error without mercy. In actual development, structure pointers are used more frequently because dynamic memory allocation and function parameter passing often require pointer operations.

Initialization

If a structure variable is declared but not initialized, the member values will be random, like garbage data left in the stack. In development, this uninitialized issue can be the culprit behind crashes or data anomalies. While manually assigning values one by one is possible, it is cumbersome. The C89 standard supports initialization in declaration order:

struct sensor_data s1 = {

'A',

100,

1234.5678,

"TempSensor"

};

This method looks simple, but there is a significant pitfall: you must ensure that the initialization values are in the exact same order as the structure member declarations. If the structure has as many as twenty or thirty members, or if new members are added during development, getting the order wrong can lead to hidden dangers. Fortunately, C99 introduced designated initialization syntax, which comes to the rescue:

struct sensor_data s1 = {

.id = 'A',

.value = 100,

.timestamp = 1234.5678,

.name = "TempSensor"

};

This syntax explicitly specifies the value for each member, making it less prone to errors even if the structure definition changes. In project development, it is recommended to always use C99 designated initialization.

Dynamic Allocation: Structures on the Heap

Structures can not only be defined on the stack but can also be dynamically allocated on the heap using malloc, which is suitable for scenarios where the size needs to be determined at runtime. For example:

struct sensor_data *sp = malloc(sizeof(struct sensor_data));

if (sp == NULL) {

// Memory allocation failed, handle it promptly

printf("Memory shortage, allocation failed!\n");

return -1;

}

memset(sp, 0, sizeof(struct sensor_data)); // Clear to prevent random values

sp->id = 'C';

sp->value = 300;

// Don't forget to free when done

free(sp);

There are several key points here: first, always check if the pointer is NULL after allocation; memory shortages are common in embedded devices; second, the allocated memory is uninitialized, so it is best to use memset to clear it; third, you must free the memory when done, or memory leaks will eventually cause your device to freeze.

Nesting and Self-Referencing – Advanced Uses of Structures

Structures can be nested, like Russian dolls. For example, defining a 2D coordinate point and a sprite structure:

typedef struct {

float x;

float y;

} Point2D;

typedef struct {

char *name;

Point2D pos;

uint8_t *image;

} Sprite;

Initializing nested structures is also straightforward:

Sprite s = {

.name = "Enemy",

.pos = {.x = 1.0f, .y = 2.0f},

.image = some_data

};

However, if you want the structure to contain itself, such as implementing a binary tree, it becomes more complicated. Writing directly:

struct tree {

struct tree left;

struct tree right;

int data;

};

will result in an error because this leads to infinite recursion and unbounded memory usage. The solution is to use pointers:

struct tree {

struct tree *left;

struct tree *right;

int data;

};

This self-referencing structure is common in development, such as implementing linked lists or tree data structures. However, be cautious, as pointer operations can easily lead to dangling pointers or wild pointers, requiring extra care during debugging.

Memory Alignment

The layout of structures in memory is not simply a matter of placing members one after another. The C standard specifies that members are arranged in declaration order, but the compiler may insert padding bytes between members or at the end, which is known as memory alignment. Why is alignment necessary? Because modern processors (like ARM or x86-64) access aligned memory addresses faster, and some architectures (like SPARC) may crash if not aligned.

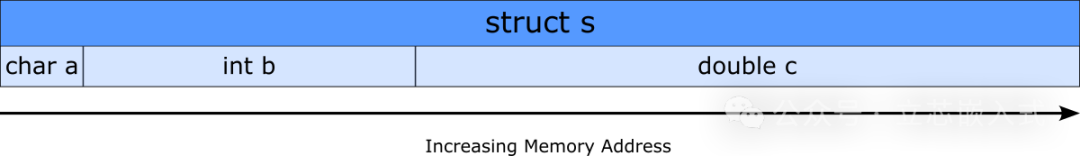

Let’s look at an example:

struct example {

char a; // 1 byte

int b; // 4 bytes

double c; // 8 bytes

};

You might think this structure occupies 1+4+8=13 bytes, but in x86-64, it may actually be 24 bytes. Why? Because the compiler inserts padding bytes to ensure that each member’s address meets its alignment requirements:

- char does not require alignment and occupies 1 byte.

- int requires 4-byte alignment, so 3 bytes of padding may be added before it.

- double requires 8-byte alignment, so 4 bytes of padding may be added before it.

The memory layout may look like:

[char a][pad 3][int b][pad 4][double c][pad 8]

The total size is padded to a multiple of 8 (the alignment requirement of the largest member). You can use the offsetof macro to check offsets:

printf("Offset of b: %zu\n", offsetof(struct example, b)); // may output 4

printf("Offset of c: %zu\n", offsetof(struct example, c)); // may output 8

Want to know the actual layout? Add the -Wpadded parameter when compiling with Clang, and the compiler will directly tell you where padding has been added. This trick is particularly useful during debugging.

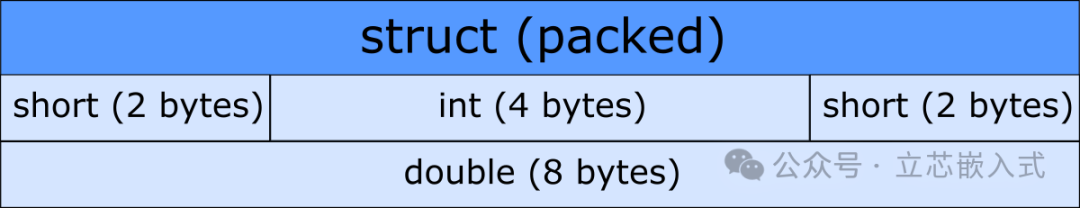

Packed Structures: The Cost of Saving Space

If you need to ensure that a structure does not have padding (for example, when mapping hardware registers or file formats), you can use the GCC/Clang attribute((packed)):

struct example {

char a;

int b;

double c;

} __attribute__((packed));

In this case, the structure size is 13 bytes, with no padding. But don’t celebrate too soon! Packed structures can lead to unaligned accesses, which not only degrade performance but may also crash on certain architectures. In embedded development, unless explicitly needed (like operating on peripheral registers), it is best to avoid using packed, as the cost of filling in the pits can be high.

Bit Fields: Economical Storage

In resource-constrained embedded systems, bit fields are a great tool for saving space. For example, to store 8 flags, using 8 bool types would be wasteful, as each bool occupies 1 byte. Bit fields can be written like this:

struct flags {

unsigned int f1 : 1;

unsigned int f2 : 1;

unsigned int f3 : 1;

unsigned int f4 : 1;

unsigned int f5 : 1;

unsigned int f6 : 1;

unsigned int f7 : 1;

unsigned int f8 : 1;

};

Here, each flag occupies only 1 bit, so 8 flags fit perfectly into 1 byte! Bit fields can also do more, such as simulating characters for old terminals:

struct term_char {

unsigned int ch : 7; // 7-bit ASCII

unsigned int fg : 11; // foreground color

unsigned int bg : 11; // background color

unsigned int bold : 1; // bold

unsigned int italic : 1; // italic

};

However, bit fields also have pitfalls: the memory layout may differ across different compilers, leading to poor portability; and you cannot take the address of bit field members. Therefore, when using bit fields, it is best to confirm the layout with debugging tools to avoid detours.

Flexible Arrays: Dynamic Size Tail

C99 introduced flexible array members, allowing the last member of a structure to be an array of unspecified size. For example:

struct packet {

int len;

char data[];

};

When allocating, you can decide the array size based on your needs:

int size = 50;

struct packet *p = malloc(sizeof(struct packet) + size * sizeof(char));

p->len = size;

This is particularly useful for handling variable-length data (like network packets or logs). However, note that flexible arrays must be the last member, and you need to account for the extra space when allocating.

Conclusion

Structures are one of the souls of the C language, especially in embedded development. When used well, they can make the code clear and efficient; when used poorly, they can lead to a pile of pitfalls waiting for you to fill.

From basic declarations to memory alignment, and from bit fields to flexible arrays, each feature of structures has its place, but there are also many details to pay attention to. When writing code, make good use of tools to check memory layouts, and be vigilant during debugging.