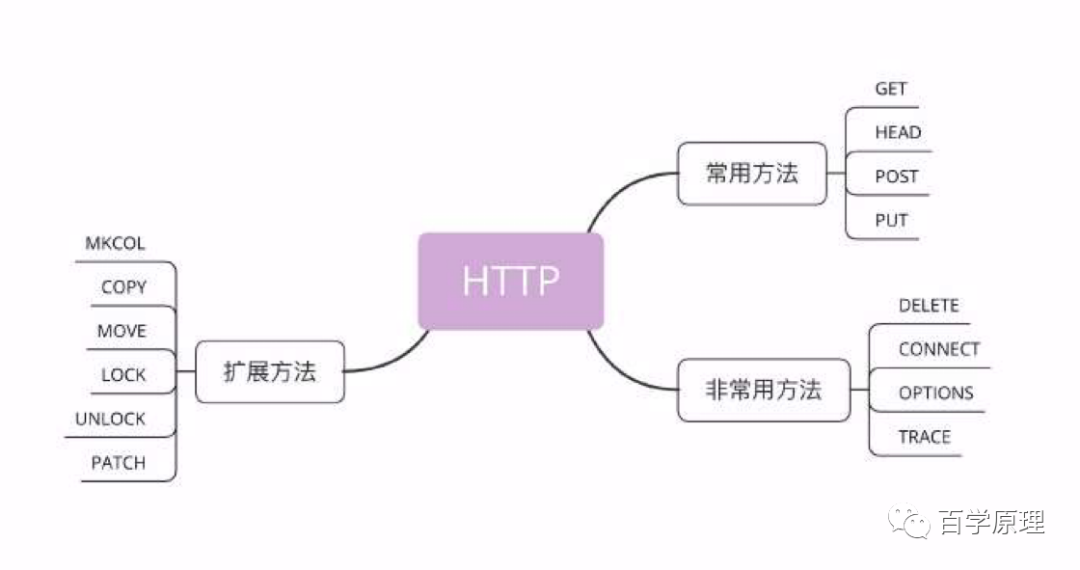

Mind Map

-

What was the original intention behind the design of this request method? -

Has there been any change in its practical use compared to the initial design? What are its typical uses today?

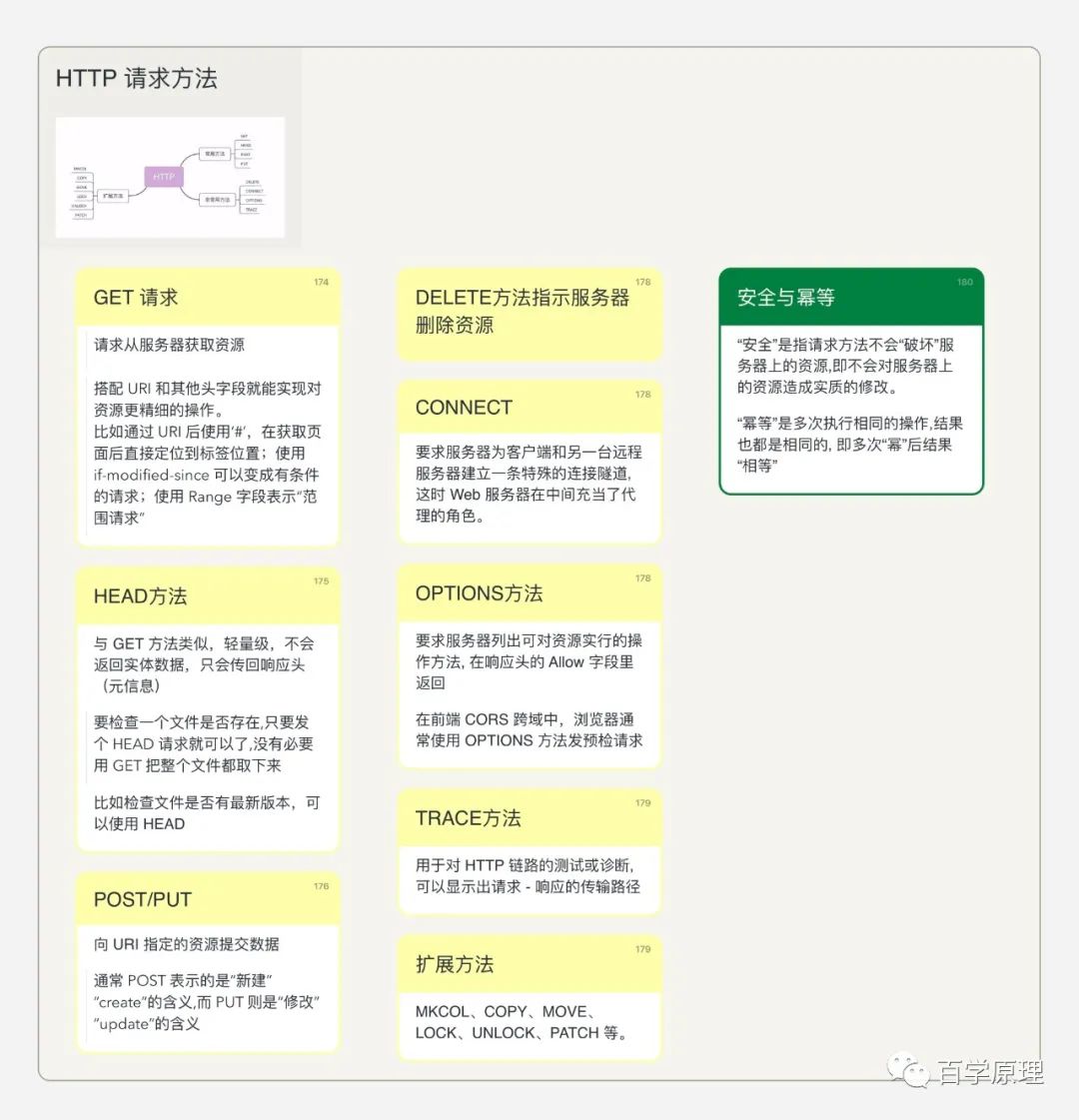

Safety and Idempotence

First, let’s understand the concepts of safety and idempotence in the HTTP protocol:

-

“Safety” means that the request method will not “harm” the resources on the server; that is, it will not cause any substantial modifications to the resources on the server. -

“Idempotence” means that executing the same operation multiple times will yield the same result; that is, after multiple “idempotent” operations, the result remains “equal,” similar to the concept in mathematics.

GET Request

The GET request is the first request method that appeared in the HTTP protocol. In the world of HTTP/0.9, all documents were read-only.

Its intended purpose is for the client to request resources from the server. In the specific RFC 7231, it has the following characteristics:

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Does the request have a body? | No |

| Does the response have a body? | Yes |

| Is it safe? | Yes |

| Is it idempotent? | Yes |

| Is it cacheable? | Yes |

In practical use, combining URI and other header fields allows for more precise operations on resources.

-

For example, using #after the URI allows direct navigation to a tag location after retrieving the page; -

Combining with the if-modified-sinceheader field can turn it into a conditional request; -

Combining with the Rangeheader field indicates a “range request” (which can be used to request parts of large files).

HEAD Request

The HEAD request can be seen as a lightweight version of the GET method. It does not return entity data (even if there is a body, it should be ignored), only the response headers (metadata).

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Does the request have a body? | No |

| Does the response have a body? | No |

| Is it safe? | Yes |

| Is it idempotent? | Yes |

| Is it cacheable? | Yes |

The purpose of its design is to save bandwidth (one of the causes of latency).

What are its practical uses?

-

It can be used to check if a large file exists. Just send a HEAD request without needing to use GET to retrieve the entire file. -

Check if a file has a newer version using HEAD.

POST/PUT

Both methods are used to submit data to the resource specified by the URI, with the POST method being used more frequently.

What is the difference between the two?

From the original design intent of the HTTP protocol, POST indicates the meaning of “create,” while PUT indicates “update.” In other words, the PUT method is idempotent, while POST is not idempotent (for example, submitting an order multiple times).

It is important to understand that the HTTP protocol is not a strict protocol. That is to say, if the client and server negotiate the protocol content (for example, misuse request methods), it is also acceptable.

POST Method

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Does the request have a body? | Yes |

| Does the response have a body? | Yes |

| Is it safe? | No |

| Is it idempotent? | No |

| Is it cacheable? | Only if freshness information is included |

We typically have two ways to use the POST method:

-

Send an HTML form and return the modification result from the server (This was the original use of POST, as forms were an important part of web pages at that time). In this case, the body type (content type) is often determined by the form’s attributes, usually having the following three possibilities:

POST / HTTP/1.1 Host: foo.com Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded Content-Length: 13 say=Hi&to=MomPOST /test.html HTTP/1.1 Host: example.org Content-Type: multipart/form-data;boundary="boundary" --boundary Content-Disposition: form-data; name="field1" Content-Type: text/plain value1 --boundary Content-Disposition: form-data; name="field2"; filename="example.txt" value2If you observe closely,

multipart/form-dataandmultipart/byterangesare used in a similar way. RFC 7231 specifically uses Multipart Types to refer to these two MIME types. The former is generally used for handling form data, while the latter is usually used in range requests (some 206 Partial Content responses).One may wonder about the meaning of boundary and why each segment has a corresponding header field (such as content-type)?

As the name suggests, boundary means the boundary used to separate the contents between different segments. Each segment has a corresponding header field because the RFC specification needs to consider many special cases, including the situation where multiple contents with different encoding methods are transmitted, hence the design of corresponding header fields. In actual use, we can choose to use them or not.

-

text/palin: just means literally. -

multipart/form-data:application/x-www-form-urlencodedworks fine when handling ASCII characters. However, in reality, after internationalization, network packets are filled with a large number of non-ASCII characters, such as Chinese. The Chinese character “中” in UTF-8 is 3 bytes, but after URL encoding, it becomes 9 bytes, which is unacceptable for bandwidth; we prefer not to unnecessarily increase the body size during transmission (compression is even better), which is whymultipart/form-datacame into existence. -

application/x-www-form-urlencoded: as the name suggests, uses URL encoding to encode data into the formatx=y&z=k. You will find that this method is similar to adding params in the GET method. What is the difference between the two? The GET method directly displays params in the browser’s address bar, while POST places them in the body.

The second way is to use POST requests through XMLHttpRequest.

It is important to note that XMLHttpRequest is not defined by the HTTP protocol but is maintained by the WAHTWG community.

When using XHR to perform POST requests, the body type can be any type specified in HTTP. As designed in the HTTP 1.1 specification, POST is expected to uniformly complete the following functions:

-

Annotation of existing resources -

Publishing messages on various web pages (one of the main functions of the web) -

Registering new users -

Providing data to data processors, such as submitting forms -

Extending database data through append operations

PUT Method

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Does the request have a body? | Yes |

| Does the response have a body? | Yes |

| Is it safe? | No |

| Is it idempotent? | Yes |

| Is it cacheable? | No |

In addition to the fact that the PUT method is idempotent, another distinction is that the PUT method does not appear in HTML forms and is not cacheable.

PUT /new.html HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Content-type: text/html

Content-length: 16

<p>New File</p>So, what details are there regarding the response for PUT requests?

-

If the target resource does not exist and the PUT method successfully creates one, the response status code must be 201 (Created)to notify the client that the resource has been created.

HTTP/1.1 201 Created

Content-Location: /new.html-

If the resource already exists but has been successfully updated using the PUT method, the server must return 200or204 (No Content)to indicate that the request was successful.

HTTP/1.1 204 No Content

Content-Location: /existing.htmlDELETE Method

This method is used to instruct the server to delete a resource. It is widely used in RESTful architecture.

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Does the request have a body? | May have |

| Does the response have a body? | May have |

| Is it safe? | No |

| Is it idempotent? | Yes |

| Is it cacheable? | No |

If the DELETE method is executed successfully, the following status codes may apply:

-

202 (Accepted): Indicates that the request operation may be successfully executed, but has not yet started. -

204 (No Content): Indicates that the operation has been executed, but there is no further related information. -

200 (OK): Indicates that the operation has been executed, providing relevant status information in the response.

CONNECT Method

The CONNECT method is rarely used in actual web development. However, it should be noted that HTTP is not just a “web” protocol; it has very powerful functionalities.

The primary role of this method is HTTP proxy (for sensitive reasons, cannot elaborate), simply put, it requests the server to establish a special connection tunnel for the client to another remote server, with the web server acting as a proxy in between.

The CONNECT method directly connects to the proxy server via TCP, as shown below:

CONNECT www.xxx.com:80 HTTP/1.1

Host: www.web-tinker.com:80

Proxy-Connection: Keep-Alive

Proxy-Authorization: Basic *

Content-Length: 0Proxy-Authorization is used for authentication.

To specifically apply HTTP proxy in practice, it involves related encryption operations, which I cannot elaborate on.

OPTIONS Method

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Does the request have a body? | No |

| Does the response have a body? | No |

| Is it safe? | Yes |

| Is it idempotent? | Yes |

| Is it cacheable? | No |

Initially, the OPTIONS method was used to request the server to list the operations that can be performed on the resource, and to return them in the Allow field of the response header. curl -X OPTIONS http://example.com -i

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Allow: OPTIONS, GET, HEAD, POST

Cache-Control: max-age=604800

Date: Thu, 13 Oct 2016 11:45:00 GMT

Expires: Thu, 20 Oct 2016 11:45:00 GMT

Server: EOS (lax004/2813)

x-ec-custom-error: 1

Content-Length: 0Later, with the emergence of the CORS mechanism, browsers use the OPTIONS method to send preflight requests. The specifics of how CORS uses the OPTIONS method will be discussed in another article.

TRACE Method

The TRACE method is a debugging method provided by the HTTP protocol, used for testing or diagnosing HTTP links, and can display the transmission path of requests and responses (loop-back test); it is not commonly used in actual development.

Extended Methods

Common HTTP extended methods include MKCOL, COPY, MOVE, LOCK, UNLOCK, PATCH, etc. In other words, they do not appear in the specific content of the HTTP protocol. They are often first extended by various application vendors and then widely applied in the industry. When the IETF sees that these have become established conventions, they supplement these related methods.

PATCH Method

The PATCH method is a supplement to the PUT/POST methods, used for partial modifications to resources and is non-idempotent. RFC5789

First, we need to determine whether a server supports the PATCH method:

-

Check via the Allow or Access-Control-Allow-Methods fields. -

Look for the presence of Accept-Patch.

PATCH /file.txt HTTP/1.1

Host: www.example.com

Content-Type: application/example

If-Match: "e0023aa4e"

Content-Length: 100

[description of changes]HTTP/1.1 204 No Content

Content-Location: /file.txt

ETag: "e0023aa4f"