For many Chinese readers, the first obstacle to reading Russian literature, especially lengthy Russian novels, is the seemingly endless and ever-changing names of the characters. This barrier is not insurmountable: some necessary annotations, a bookmark with a list of character names—ultimately, the care and thoughtfulness of the translator and editor can help readers overcome this challenge. A greater difficulty arises from the language itself: to readers without knowledge of the original text, the names of the characters in the works are merely a series of difficult phonemes. However, the profound and thoughtful authors never casually name their characters; these names can reveal the prototypes of the characters in real life, disclose their ethnicity, profession, and personality traits, and indicate the author’s attitude towards the characters. More deeply, they carry strong symbolic meanings, serving as a key to understanding the character’s image and even the main theme of the entire work.

In Chinese literature, the literary quality of character names is often endowed by their given names, courtesy names, or nicknames, as surnames can only be chosen from a limited range, while naming allows for more creative freedom. In contrast, under the influence of monotheistic traditions in Russia, the situation is quite the opposite: given names and patronymics can often only be selected from a limited number of Christian names, while surnames are less restricted and can be freely invented.

Among the “name poets” of Russia, Leo Tolstoy is a representative who adheres to convention and honesty. The names of his protagonists are often simple variations of their prototypes’ names, such as Paul Bolkonski (Bolkonskiy), which is derived from his prototype Volkonskiy with slight adjustments. The name Levin also indicates that his prototype is Tolstoy himself (Lev → nickname Lëva → name transformed into surname Lëvin → Levin). Others are not satisfied with such simple variations; 18th-century comic poets often loved to create highly metaphorical surnames for their protagonists. For example, in Fonvizin’s “The Minor”, the antagonists are named Prostakov (Prostakov, fool) and Skotinin (Skotinin, livestock), while the protagonists are Pravdin (Pravdin, truth) and Starodum (Starodum, old and wise), making the character images quite clear. Gogol further developed this tradition, and it is said that when people read his comedies, they would burst into laughter upon encountering the character names.

Dostoevsky inherited and greatly deepened this tradition, becoming a master of this style. Below, we will take some character names from “Crime and Punishment” as examples to glimpse the charm of Dostoevsky’s “name poetics”.

1Rodion Romanovich Raskol’nikov

Raskol, meaning split. This word precisely captures the characteristics of the protagonist’s personality and worldview: kindness and cruelty, gentleness and rage coexist, with a tendency to extremes, struggling between faith and doubt, harboring noble ideals of salvation while firmly believing that any means can be justified to achieve those ends.

In a historical context, raskol specifically refers to the church schism that occurred in mid-17th century Russia, where the dissenters (raskol’nik) who refused to accept the religious reforms were brutally persecuted by the Tsarist regime, willing to resist in extreme forms and vowing to uphold their faith at all costs. Dostoevsky had deep contact with the persecuted dissenters during his time in a labor camp, and his depictions of dissenters often portray them as fanatics who believe that suffering is the only path to redemption, even willing to pursue suffering unconditionally (the painter Mikolka, who takes the murder charge upon himself in the novel, is one such example). Raskol’nikov’s mother mentions: “The surname Raskol’nikov has been known for two hundred years,” and in her letter to Raskol’nikov, she notes that their hometown is R Province (referring to Ryazan Province). Looking back two centuries from the time the story takes place, it coincides with the time of the church schism, and the area around Ryazan was the heartland of the dissenters, subtly hinting at Raskol’nikov’s connection to the schism. It is no wonder that detective Porfiry Petrovich hints to Raskol’nikov that deep down, he also has a tendency to bear the suffering of the dissenters, and Svidrigailov views Raskol’nikov’s sister Dunya in the same light—this is clearly Raskol’nikov’s “family hereditary disease”! In Dostoevsky’s works, the schism is not only linked to religious history but is also seen as a dual result of Peter the Great’s reforms—at the lower levels, it exacerbated the church schism, giving rise to more dissenters, while at the upper levels, it led to a division between the nobility, intellectuals, and the people, resulting in nihilism. Raskol’nikov embodies both forms of schism.

The protagonist’s name, patronymic, and surname all begin with the Ra- sound (the Ro- in the name and patronymic needs to be softened to Ra-), resembling ominous thunder. The schism even appears in the structure of his name. Rodion’s etymology comes from the Greek word for “Rhodes man,” while the patronymic Roman comes from the Latin word for “Roman.” Greek and Roman, Orthodoxy and Catholicism coexist within one person. Considering Dostoevsky’s hostile attitude towards Catholicism, their relationship can only be one of life-and-death struggle, rather than harmonious coexistence. Meanwhile, Raskol’nikov’s mother and sister always call him Rodya, Rodenka, and other affectionate forms (over a hundred times). To ordinary Russians without linguistic knowledge, “Rodya” easily evokes words filled with “centripetal force” such as rod (clan, kind), rodnoy (kin, relative), and rodina (hometown), symbolizing the protagonist’s intrinsic connection to the land, the people, and Russia, in stark contrast to the nihilistic tendencies emphasized in “Raskol’nikov” that highlight division and centrifugal forces.

Thus, the struggle between “Rodion” and “Raskol’nikov” becomes the thread of the entire novel. When the protagonist finally decides to go to the police station to confess, it is the moment when “Rodion” ultimately triumphs over “Raskol’nikov,” and the seemingly perplexing dialogue between him and Lieutenant Porfiry takes on profound symbolic significance:

—To be honest… what is your name? What? Sorry…

—Raskol’nikov.

—What? Raskol’nikov! Do you really think I would forget this! Please don’t think too highly of me… Rodion… Ro… Ro… is it Rodionovich, I believe?

2Sof’ya Semënovna Marmeladova

Marmelad, meaning citrus jam, soft candy. Her father succumbed to debauchery, drank himself to death, and was crushed under a wheel; her mother died of tuberculosis, the eldest daughter was forced into prostitution, and the younger children were destined for orphanages, repeating the tragic fate of their elders. Dostoevsky condenses the suffering he witnessed in the Petersburg slums into one family, yet gives them such a sweet surname. This irony reveals the writer’s deep sympathy and helplessness towards human suffering.

Sof’ya derives from the Greek word for “wisdom,” and in Dostoevsky’s works, the Christian virtues of humility and obedience are synonymous with this wisdom. Besides Marmeladova, several other characters named Sof’ya appear in Dostoevsky’s works: Sof’ya Matveyevna Ulitina, a gospel salesman in “The Possessed”; Sof’ya Ivanovna Karamazov, the second wife of old Karamazov in “The Brothers Karamazov”; and Sof’ya Andreyevna, the protagonist’s biological mother in “The Adolescent”—all of whom are “submissive women” like Marmeladova.

3Arkadiy Ivanovich Svidrigaylov

Russian readers can immediately tell that this is not a typical Russian surname. There was once a Lithuanian prince named Švitrigaila (Svidrigailo in Russian). Dostoevsky was well aware of his paternal lineage’s Lithuanian origins and had been interested in Lithuanian history, likely knowing of this prince’s existence. The -gail- in his name may have reminded him of the German word geil (lecherous), thus he chose this surname for his lecherous character.

Moreover, in the mid-19th century, the magazine “Iskra” was extremely popular in the Russian provinces, and its most popular column, “Letters from the Audience,” reported various scandals in provincial towns. However, censorship prohibited the mention of real names or places in such pieces, so the magazine’s editors invented a series of names corresponding to real locations and characters, and Svidrigaylov became a code name for a villainous nobleman from a city in Ukraine—no wonder this peculiar surname carries some southwestern Russian dialect flavor: svidïy, meaning sour, khailo, meaning throat. When Dostoevsky was writing “Crime and Punishment,” his brother Andrey had just visited that city and found that this name was well-known among locals, even becoming a common noun (for comparison, in “Crime and Punishment,” when Raskol’nikov sees a pervert attempting to assault a woman on the boulevard, he scolds him, saying, “You Svidrigaylov!”). It is likely that he shared this interesting observation with his brother upon returning to Petersburg. By giving his character this widely recognized name, the writer imbues it with the associations that the name brings to readers: a typical old-style landlord who behaves atrociously.

However, Dostoevsky does not intend to follow this path of social criticism; on the contrary, he constantly engages in debates with these journalists. In the dialogue between Svidrigaylov and Raskol’nikov, Svidrigaylov’s words are filled with parody and irony towards “Iskra.” Regardless of character, psychology, or thought, Dostoevsky’s protagonist is much deeper than the one-dimensional, flat villain in the magazine, and by naming his character Svidrigaylov, Dostoevsky, as an artist and thinker, rebuts those media figures who only expose the dark sides of society—what you pursue as “truth” is merely one dimension of reality.

4Pëtr Petrovich Luzhin

Compared to the complex and profound Svidrigaylov, his compatriot Luzhin’s name is much simpler and more crude: Luzha, meaning pond. Luzhin’s soul is just like this pond, small and dirty. Peter, derived from the Greek word for “rock,” Pëtr Petrovich, the rock among rocks, reveals his cold-hearted nature. Luzhin is a collective representation of the new generation of bourgeois in Dostoevsky’s eyes.

5Lizaveta Ivanovna

This name immediately reminds Russian readers of a famous Lizaveta Ivanovna in Russian literature—the heroine of Pushkin’s “The Queen of Spades.” The similarity in names echoes the similar fates of the two characters: both Lizas must live under the watchful eye of a malicious old woman; Pushkin’s Hermann kills the countess, destroying Lizaveta’s happiness, while Raskol’nikov, after killing Alyona Ivanovna, also silences the innocent Lizaveta Ivanovna.

6Dmitriy Prokof’evich Razumikhin

Razumikha, meaning rational (female). In terms of Razumikhin’s literary image, this “rationality” refers more to character than to thought or philosophy; more precisely, this “rationality” actually refers to prudence (rassudok). No wonder Luzhin mistakenly refers to Razumikhin as Rassudkin in one dialogue. Having an outsider accidentally mispronounce a character’s name may seem like an unnecessary detail, but it actually reveals the connotation of the character’s name through the process of error and correction, a literary game that Dostoevsky often enjoys.

6Andrey Semënovich Lebezyatnikov

Lebezyat’, meaning to flatter, to ingratiate. In the manuscript, Raskol’nikov tells Razumikhin that one must first possess some property to pave the way for future ideals; otherwise, one must “flatter, ingratiate (lebezit’), and agree with others. Imagine the scene of having to ingratiate oneself (lebezyatnichestvo) before Luzhin while being destitute.” Targeting the main opponents of the novel, the radical progressive youth represented by Chernyshevsky in the 1860s, Dostoevsky wrote in the manuscript: “Nihilism is the servility of thought, and nihilists are the slaves of thought.” Lebezyatnikov is a caricature of the nihilists of the time: they are both slaves to their own thoughts and to new bourgeois figures like Luzhin.

In “Crime and Punishment,” there are two Mikolka (Mikolka): one is the dissenting painter at the murder scene, who takes on the murder charge of another just to bear suffering and seek redemption; the other is the coachman in Raskol’nikov’s nightmare before committing the crime, who, in a fit of beastly desire, beats his horse to death. These two characters with the same name actually embody Raskol’nikov’s dual personality (a common technique used by Dostoevsky). On the other hand, Mikolka is a diminutive form of Nikolay, a very common name in Russia, especially in rural areas. Without a patronymic or surname, only a very ordinary name, in this sense, the two Mikolka not only symbolize the protagonist’s duality but also the duality of the Russian people—every Russian deep down is both the angelic painter Mikolka and the devilish coachman Mikolka.

Even for some minor characters, Dostoevsky often endows them with meaningful names. Sonia, having become a prostitute, cannot stay with her parents after obtaining her license and moves into the apartment of Kapernaumov. The only two descriptions of this family in the text are quite bizarre: Kapernaumov is lame, cross-eyed, and has a strange appearance; his wife and all the children seem to be permanently frightened, with stiff faces and open mouths, and the whole family speaks unclearly. The surname Kapernaumov clearly derives from the biblical place name Kapernaum. Jesus, who was not welcomed in his hometown of Nazareth, thrived in Kapernaum, healing the sick, casting out demons, and gathering disciples. The Kapernaumov family takes Sonia in, just as the Kapernaum people accepted Jesus, and this lame, cross-eyed, and unclear-speaking Kapernaumov family is not unlike those Kapernaum people who came to Jesus for healing.

However, the story does not end there. In mid-19th century Petersburg, “Kapernaum” also became synonymous with cheap taverns, and the first mention of Kapernaumov occurs in a “Kapernaum” where the frequent patron, Semyon Marmeladov, speaks—this is less a coincidence and more like a carefully arranged joke by the writer. A more subtle point is that the creators of the aforementioned “Iskra” magazine were all well-known patrons of “Kapernaum,” so when Dostoevsky says that the Kapernaumov family speaks unclearly, he is likely also mocking the poor writing style of those journalists from “Iskra.”

Behind the name of even a minor character, there are tightly interwoven biblical stories, ideological debates, and literary pranks, which can be seen as a concentrated embodiment of Dostoevsky’s polyphonic creation. In summary, “name poetics” is an important component of Dostoevsky’s poetics; without grasping the overall context of his creation, one cannot understand his “name poetics,” and to better understand his overall creation, “name poetics” is an unavoidable aspect.

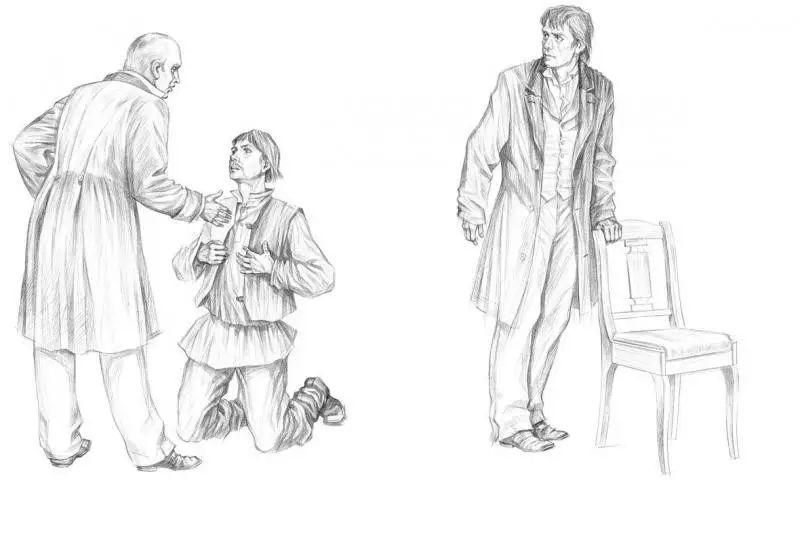

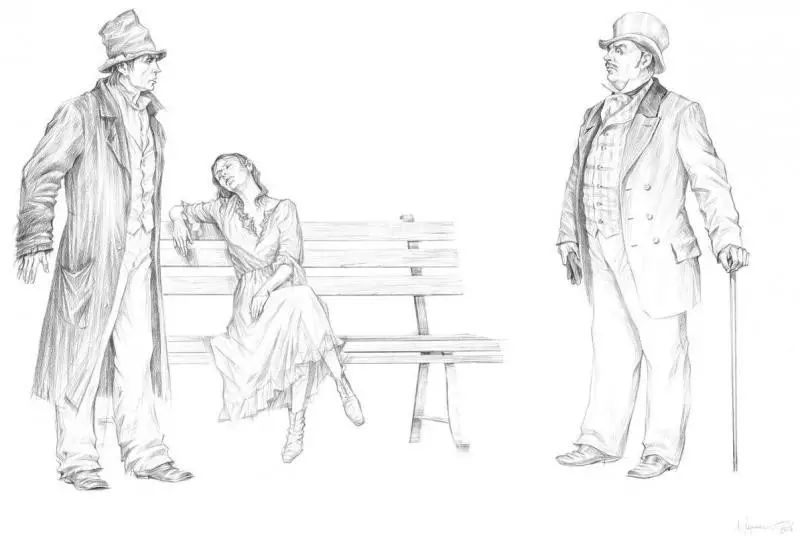

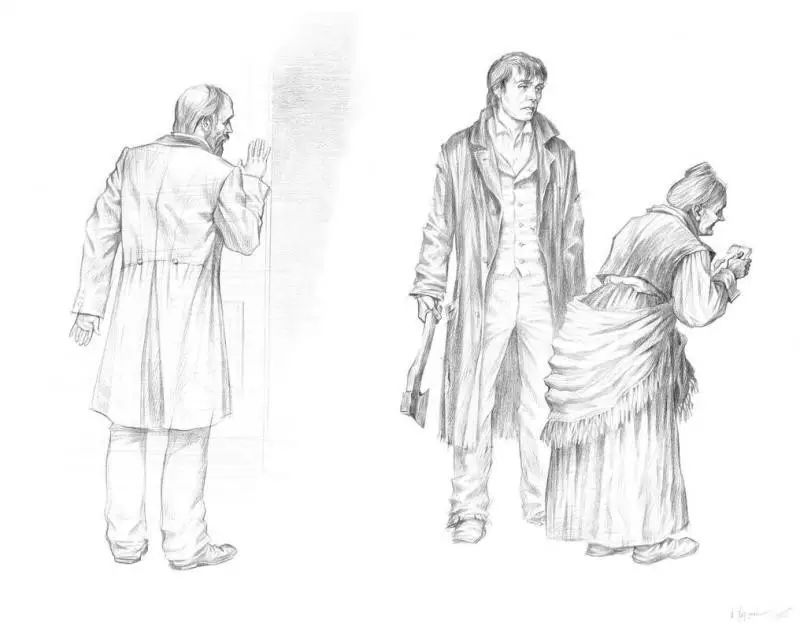

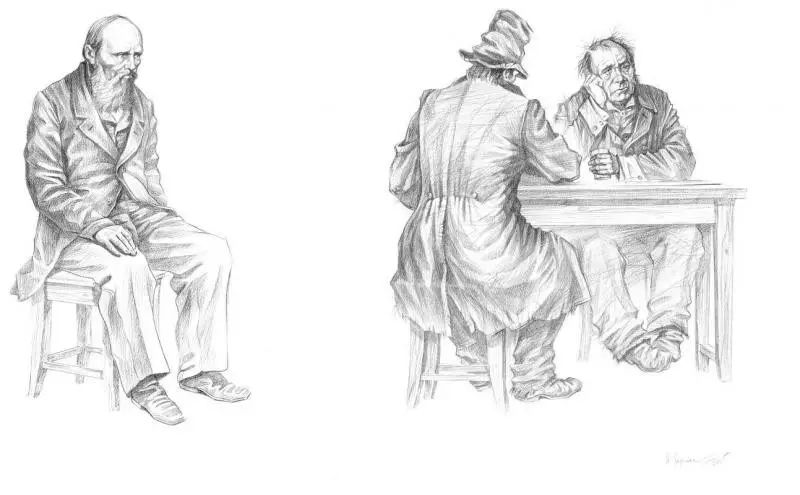

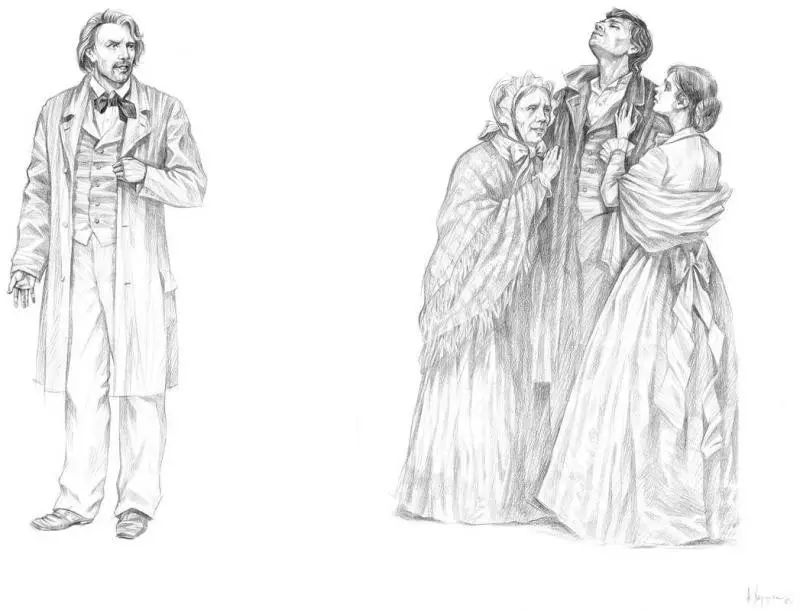

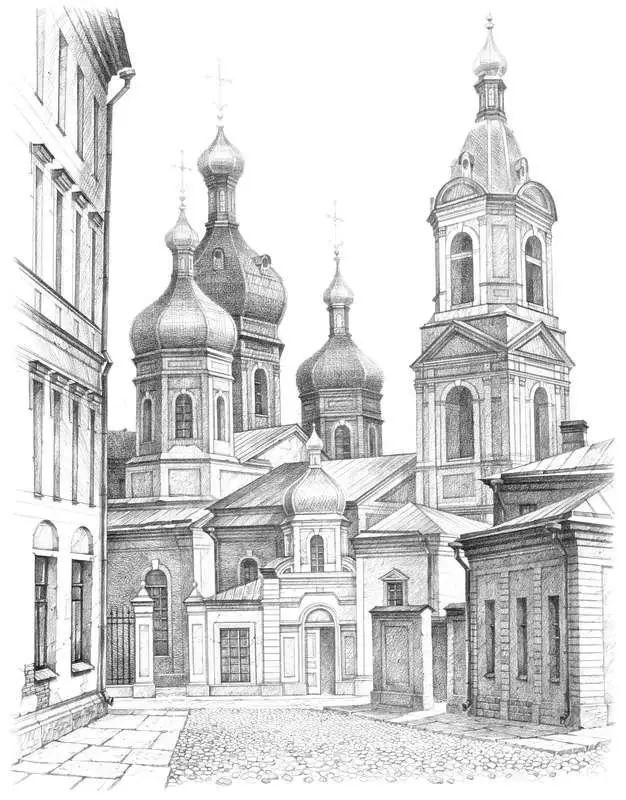

Illustration from “Crime and Punishment,” drawn by Andrey Alexandrovich Kharlashak

Click to read the original text and enter the Qing Reading store

Click the link below to view previous exciting content♥

Eileen Chang: The Self-Cultivation of a Foodie in the Republic of China

This is the highest realm of “fetishism”

The Mysterious Temptation of the Turkish Harem

On the Night of the Ghost Festival, both ghosts and people are awake

Is the White Dragon Horse actually Sun Wukong’s previous life?

The Sensual Tea Party of the Song Dynasty Could Not Do Without Courtesans

Identification complete, this is indeed a very beautiful book!