With the rapid development of neural networks and hardware (GPU) in recent years, deep learning has been widely applied in many industries including the internet, finance, driving, and security. However, during actual deployment, many scenarios such as autonomous driving and security have additional restrictions on power consumption, cost, and heat dissipation, leading to the inability to apply deep learning solutions on a large scale.

In a live class hosted by Lei Feng Network’s AI Study Club, Huang Lichao from Horizon Robotics introduced the background of AI chips and how to design efficient neural network models suitable for embedded platforms from an algorithmic perspective, applying them to visual tasks.

Outline

-

Introduce the current overview of AI chips, including the development of existing deep learning hardware and why dedicated chips need to be designed for neural networks.

-

From an algorithmic perspective, explain how to design high-performance neural network structures that meet the low power consumption requirements of embedded devices while satisfying performance requirements in application scenarios.

-

Share cost-effective neural networks and their applications in computer vision, including real-time object detection, semantic segmentation, etc.

The Current State of AI Chip Development

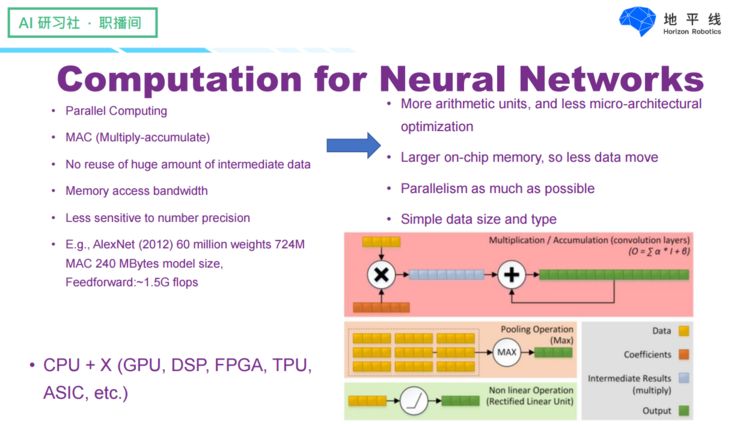

First, you can read “The History and Current Status of AI Chips.” As we all know, neural networks were initially run on CPUs. However, CPUs cannot run neural networks very efficiently because CPUs are designed for general-purpose computing and their computation mainly relies on serial processing, although some instructions can process more data simultaneously. In addition, CPUs have invested a lot of effort in optimizing multi-level caches to allow programs to read and write data relatively efficiently, but this cache design is not particularly necessary for neural networks. Furthermore, CPUs have also made many other optimizations, such as branch prediction, which are meant to make general computations more efficient, but they are additional overhead for neural networks. So what kind of hardware structure is suitable for neural networks?

Before discussing this issue, let’s start with the characteristics of neural networks:

First, the operations of neural networks have large-scale parallelism, requiring each neuron to be able to compute independently and in parallel;

Second, the basic unit of neural network operations is mainly multiplication and accumulation, which requires hardware to have enough computational units;

Third, each computation of a neuron generates many intermediate results, which are not reused, requiring the device to have sufficient bandwidth. An ideal device should have a relatively large on-chip memory and sufficient bandwidth to accommodate the network’s weights and inputs;

Fourth, since neural networks are not very sensitive to computational precision, simpler data types can be used in hardware design, such as integers or 16-bit floating-point numbers. Therefore, the neural network solutions commonly used in recent years consist of CPUs plus hardware that is more suitable for neural network computations (which can be GPUs, DSPs, FPGAs, TPUs, ASICs, etc.), forming a heterogeneous computing platform.

The most commonly used solution is CPU+GPU, which is a standard configuration for deep learning training, the advantage is that it has high computing power and throughput, and is relatively easy to program, but the problem is that GPUs have high power consumption and latency, especially in application deployment scenarios, where almost no one uses server-level GPUs.

In application scenarios, more commonly used solutions are FPGAs or DSPs, which have much lower power consumption than GPUs, but relatively higher development costs. DSPs rely on dedicated instruction sets, which can vary with the model of the DSP. FPGAs are developed using hardware languages, making the development difficulty higher. In fact, some companies also use CPU+FPGA to build training platforms to alleviate the power consumption issues of GPU training deployments.

Although many neural network acceleration solutions have just been mentioned, the most suitable is still CPU+dedicated chips. The main reason we need dedicated AI chips is that although current hardware technology is constantly evolving, the pace of development is hard to meet the computational power demands of deep learning. Among them, two points are the most important:

First, in the past, people believed that as transistor sizes shrank, power consumption would also decrease, so under the same area, its power consumption could remain basically unchanged, but this law actually ended in 2006.

The second point is that the well-known Moore’s Law has also ended in recent years.

We can see that the development of chip technology has slowed down in recent years, so we need to rely on specialized chip architectures to enhance the computational platform’s demands for neural networks.

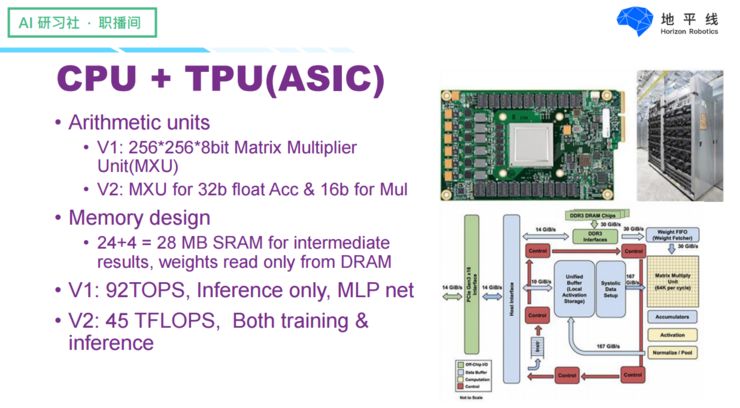

One of the most famous examples is Google’s TPU, which began development in 2013 and took about 15 months. The TPU uses a large number of multiplication units, with 256*256 8-bit multipliers; it has 28MB of cache on-chip, capable of storing network parameters and inputs. Simultaneously, data and instructions on the TPU are sent through the PCN bus, then rearranged in on-chip memory, finally computed and output back to the buffer.

The first version of TPU has a computing capability of 92 TOPS, but is only aimed at the forward prediction of neural networks, and the types of networks it supports are also very limited, mainly focusing on multilayer perceptrons.

In the second version of TPU, it can already support training and prediction, and can use floating-point numbers for training, with a single TPU having a computing power of 45 TFLOPS, which is much larger than that of GPUs.

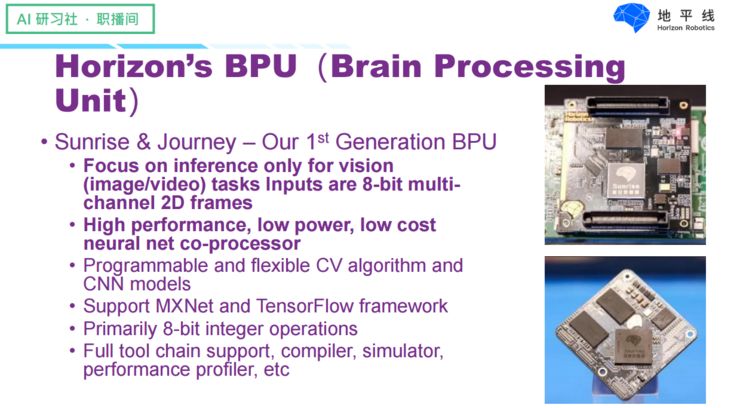

In fact, we at Horizon have also developed a dedicated AI chip called BPU. The first generation was designed in 2015 and finally taped out in 2017, with two series—the Sunrise and Journey series—both targeting computations for image and video tasks, including image classification, object detection, online tracking, etc., serving as a neural network coprocessor, emphasizing high performance, low power consumption, and low-cost solutions for embedded systems.

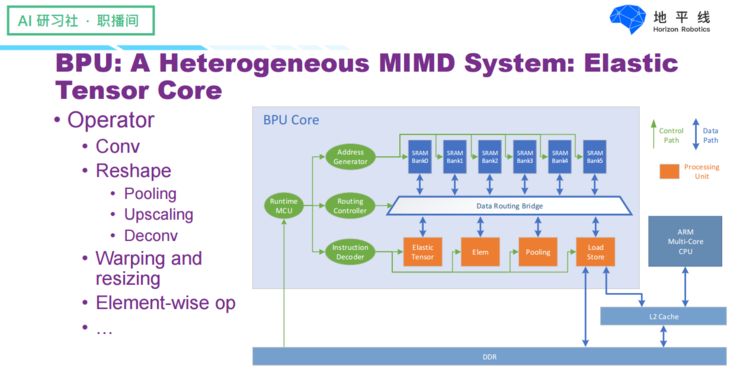

It is worth mentioning that we designed a flexible Tensor Core on our BPU architecture that can hardwareize the basic units needed for image computations, such as common operations like convolution and pooling, executing these operations very efficiently. The data is read from on-chip through a Data Routing Bridge, which is responsible for data transmission and scheduling. At the same time, all data storage resources and computing resources can be scheduled through instructions output by the editor, allowing for more flexible algorithms, including various types of model structures and different tasks.

In summary, CPU+dedicated hardware is currently a good solution for accelerating neural networks. For dedicated hardware, we can rank them based on power consumption, ease of development, and flexibility, as their energy consumption is contradictory to the other two (ease of development and flexibility)—the energy efficiency of chips is very high, but their development difficulty and flexibility are the lowest.

How to Design Efficient Neural Networks

Having discussed so much about hardware knowledge, let’s now talk about how to accelerate neural networks from an algorithmic perspective, which is also a topic of great interest to everyone.

First, let’s look at AI solutions, which can be divided into cloud AI and front-end AI based on data processing methods. Cloud AI means that we execute computations on remote servers and then send the results back to the local device, which requires the device to be connected to the network at all times. Front-end AI means that the device itself can perform computations without needing to connect to the internet, which has advantages in security, real-time performance, and applicability compared to cloud AI. In some scenarios, embedded front-end AI is the only solution.

The challenges in deploying embedded front-end scenarios lie in the limited power consumption, cost, and computing power. For example, an IP camera powered by a network cable consumes only 12.5 watts, while the commonly used embedded GPU—Nvidia TX2—consumes 10-15 watts. Although the TX2 has strong computational resources, reaching 1.5T, its price of $400 is unacceptable for many embedded solutions. Therefore, to achieve good front-end embedded solutions, we need to optimize algorithms and neural network models to the maximum extent under given power consumption and computing power constraints, meeting the needs of scenario deployment.

The ultimate goal of accelerating neural networks is to enable the network to maintain good performance while minimizing computational costs and bandwidth requirements. Some commonly used methods include network quantization, network pruning, parameter sharing, knowledge distillation, and model structure optimization. Among these, quantization and model structure optimization currently appear to be the most effective methods and have been widely adopted in the industry. Next, I will focus on these several methods.

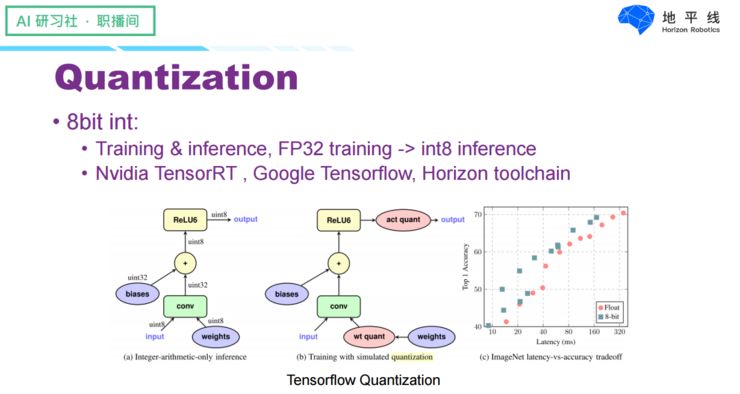

The first is quantization, which refers to discretizing continuous variables through approximation. In fact, in computers, all numerical representations are discrete, including floating-point numbers, etc., but the quantization in neural networks means running the neural network with lower bit numbers rather than directly using 32-bit floating-point numbers. Recent research has found that the precision of numerical representation does not have a significant impact on neural networks, so a common practice is to use 16-bit floating-point numbers instead of 32-bit floating-point numbers for computations, including training and forward predictions. This has been widely adopted in GPUs and Google’s second-generation TPU. Additionally, we have even found that training data with half-precision floating-point numbers can sometimes yield better recognition performance. In fact, quantization itself is a form of regularization for datasets, which can enhance the model’s generalization ability.

Furthermore, we can further compress data precision by using 8-bit integers as computation units for training and forward predictions, which reduces bandwidth to a quarter of that of 32-bit floating-point numbers. Many works have emerged in recent years adopting this approach, and it has been adopted by the industry; for example, TensorFlow Lite supports simulating 8-bit integer computations during training and actually uses 8-bit integers during deployment. Its performance in floating-point and image classification is quite comparable. Our Horizon also has similar work, where training tools use Int 8-bit for training and prediction, and our chips support models trained with MXNet and TensorFlow frameworks.

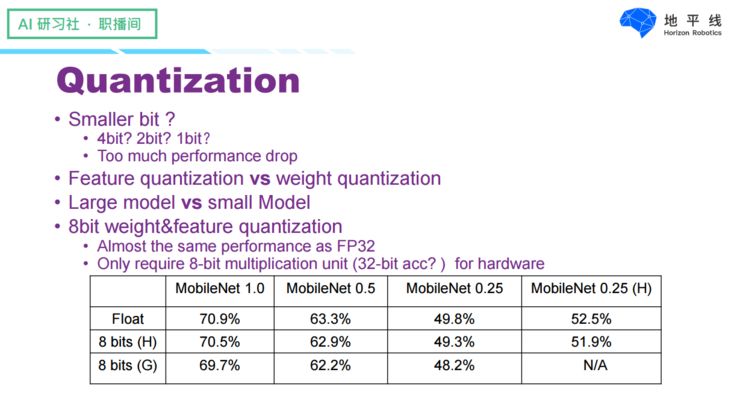

Can we lower the precision further to 4 bits, 2 bits, or even 1 bit? It is possible, but it would lead to a significant loss in accuracy, so it has not been adopted.

Quantizing neural network models can be divided into weight quantization and feature quantization. Weight quantization causes relatively little loss in output results, while feature quantization can lead to larger losses in model outputs. Additionally, the losses caused by quantization differ between large and small models; large models like VGG16 and AlexNet experience almost no loss after quantization, while small models may incur some loss. Currently, 8-bit parameter and feature quantization can be considered a relatively mature solution, capable of achieving performance comparable to floating-point and being more hardware-friendly. The table below shows the evaluation results of quantization on the ImageNet dataset, comparing Google’s TensorFlow Lite quantization scheme with our internal quantization scheme at Horizon.

We can see that regardless of whose scheme it is, the losses are actually very small. Among them, the small model MobileNet 0.25 shows a loss of about 1.6% on ImageNet with Google’s scheme, while our quantization scheme maintains a loss of less than 0.5%. Moreover, our quantization scheme matured in 2016, while Google’s was only released last year, so from this perspective, we are leading in this area in the industry.

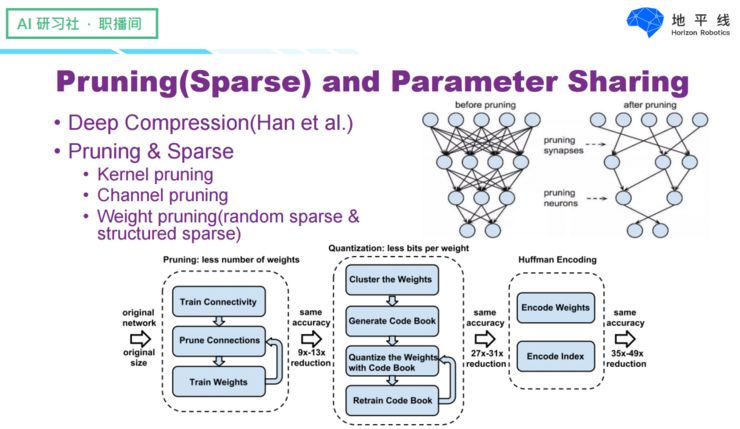

In addition to quantization, model acceleration can also be achieved through model pruning and parameter sharing. A typical case is Dr. Han Song’s representative work—Deep Compression. Pruning can be applied to entire convolution kernels, certain channels within convolution kernels, and any weights within the convolution kernels. I won’t elaborate further here; those interested can refer to the original paper.

Compared to network quantization, pruning and parameter sharing are not considered good solutions from an application perspective. This is because most research on pruning has been conducted on large models, thus yielding better results for them, while smaller models incur larger losses. Here, we refer to small models as those smaller than MobileNet and similar models. Additionally, the data sparsity caused by pruning (any structure sparsity) typically requires a significant sparsity ratio to achieve substantial acceleration. Structured sparsity acceleration is relatively easier to achieve, but it is more challenging to train. Moreover, from a hardware perspective, efficiently running sparse network structures or shared networks requires specially designed hardware to support it, which also incurs high development costs.

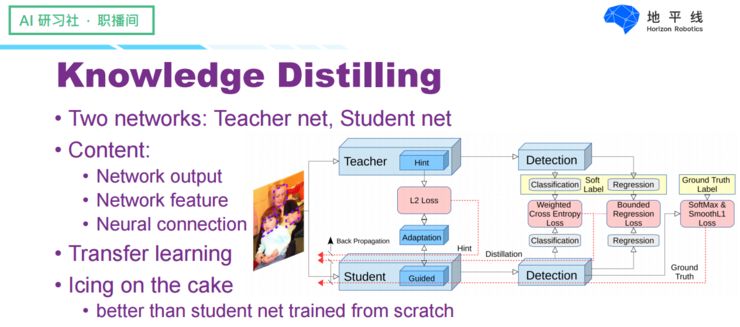

Knowledge distillation is also a commonly used model compression method, which operates on a simple principle: using a small model to learn from a large model, allowing the small model to achieve similar performance to the large model. The large model is generally referred to as the Teacher net, while the small model is called the Student net. The learning objectives include the final output layer, intermediate feature results, and network connections. Knowledge distillation is essentially a form of transfer learning and can only serve as a supplementary enhancement, yielding better results than directly training the small model with data.

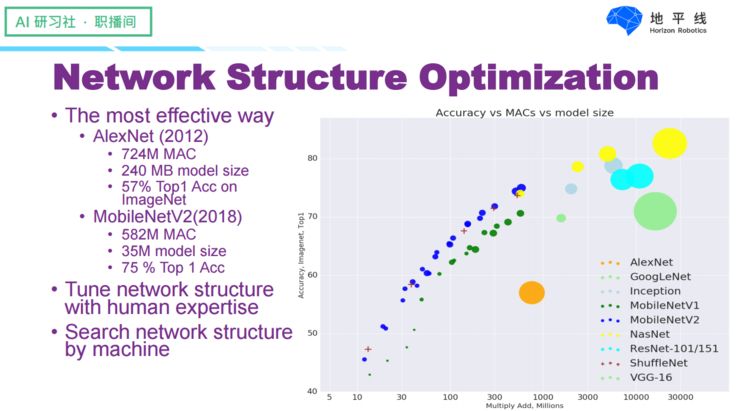

Finally, let’s talk about model structure optimization, which is the most effective way to accelerate models. As shown in the figure below, from the initial AlexNet to this year’s MobileNetV2, the parameters have been reduced from 240MB to 35MB, and the computational load has also decreased to some extent, while the accuracy in image classification has increased from 57% to 75%. The most direct way to optimize model structure is for experienced engineers to explore small model structures, and in recent years, there have also been efforts to search for model structures using machines.

Next, let’s discuss how to design an efficient neural network structure and some basic principles it should follow.

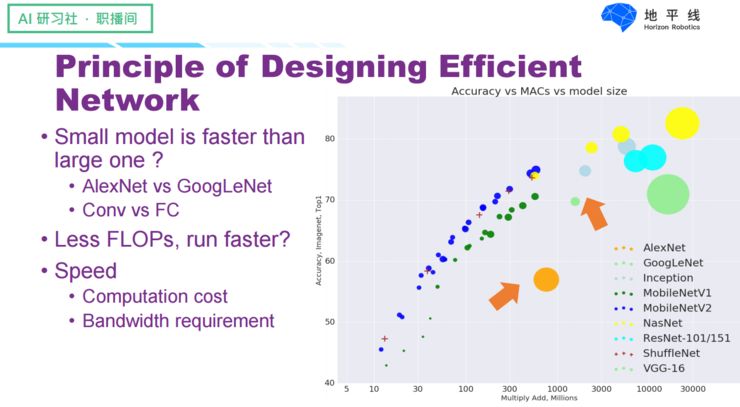

First, let’s correct a few misconceptions: First, does a smaller model run faster than a larger model? This is evidently not the case; we can observe from the arrows pointing to Google Net and AlexNet in the figure that AlexNet is clearly larger, yet it runs faster and has a smaller computational load. Second, does a smaller computational load mean a faster run? Not necessarily, because the final running speed depends on both the computational load and bandwidth; the computational load is merely one factor determining running speed.

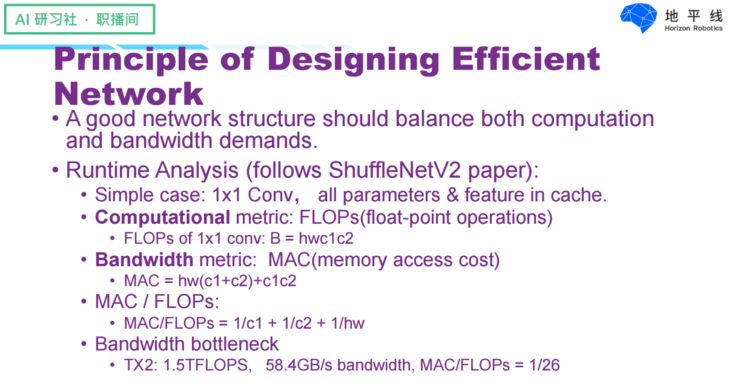

Thus, a good neural network structure that runs relatively fast must balance the demands of computational load and bandwidth. Here, we follow some viewpoints from the ShuffleNetV2 paper—although this is not our work, it is well-written, and many of its points align with conclusions we have reached during model structure optimization. In our analysis, we take 1×1 convolution as an example. Assuming that all parameters and input/output features can be placed in cache, we particularly focus on the computational load of convolution—expressed in FLOPs (Float-Point Operations) and the bandwidth represented by MAC (Memory Access Cost). At the same time, we need to pay extra attention to the ratio of bandwidth to computational load. For embedded devices, bandwidth is often the bottleneck. Taking Nvidia’s embedded platform TX2 as an example, its bandwidth is about 1:26 compared to its computing power.

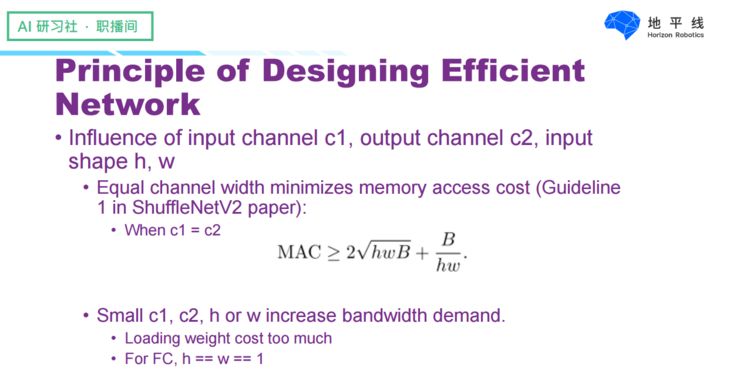

First, we need to analyze how input channel numbers, output channel numbers, and input sizes affect bandwidth and computational load. The first criterion proposed by ShuffleNetV2 is that under equal computational load, input channel numbers and output channel numbers, bandwidth is minimized, represented by the formula: In fact, if any of the input channels, output channels, or input sizes are too small, it will adversely affect bandwidth and consume a lot of time reading parameters rather than truly computing.

In fact, if any of the input channels, output channels, or input sizes are too small, it will adversely affect bandwidth and consume a lot of time reading parameters rather than truly computing.

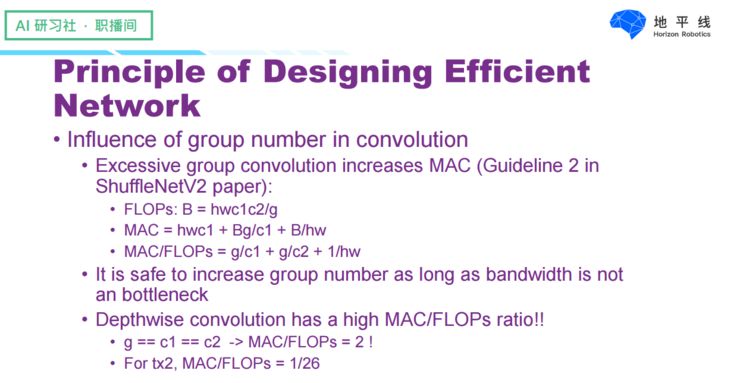

Second, how does the number of Groups in convolutions affect performance? ShuffleNetV2 points out that an excessive number of Groups increases the bandwidth per unit computational load, and we can see that the bandwidth and computational load are approximately proportional to the number of Groups. From this perspective, the Depthwise Convolution in MobileNet actually requires a significant amount of bandwidth because the ratio of bandwidth to computational load is close to 2. In practical applications, as long as bandwidth allows, we can appropriately increase the number of GROUPs to save computational load, as bandwidth is often not fully utilized.

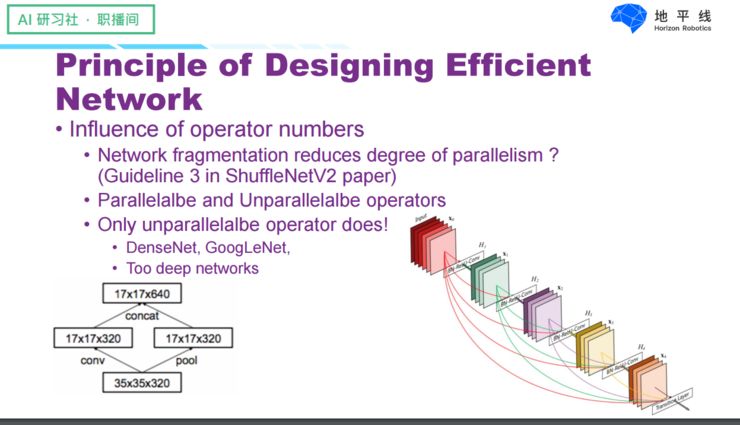

Third, ShuffleNetV2’s third criterion is that excessive network fragmentation reduces hardware parallelism, meaning we need to consider how the number of operators affects final running speed. In fact, this viewpoint from ShuffleNetV2 is not rigorous enough; to be precise, we need to categorize operators into two types: one that can be parallelized (as shown on the left), where two blocks can be computed in parallel, and the memory for concat can be pre-allocated; and another that must be computed serially, where non-parallelizable operators will reduce hardware parallelism. For hardware, parallelizable operators can fully utilize the parallel capabilities of the hardware through instruction scheduling. From this criterion, DenseNet architectures are practically very unfriendly; each convolution operation has a small computational load, and each computation relies on all previous results, preventing parallelization and resulting in slow performance. Additionally, overly deep networks also run slowly.

Finally, ShuffleNetV2 also points out that the impact of Element-wise operations on speed cannot be ignored—this can be somewhat stated. Although Element-wise operations have a small computational load, they require a significant amount of bandwidth. In fact, if we combine Element-wise operations with convolutions, the impact of Element-wise operations on final bandwidth becomes negligible. A common example is that we can combine convolutions, activation functions, and BN together, allowing data to be read only once.

At this point, let’s summarize: To design efficient neural networks, we need to enable operators to perform parallel computations while minimizing bandwidth requirements, as the final speed is determined by both bandwidth and computational load, so any bottleneck in either will restrict running speed.

Automated Design of Efficient Neural Networks

In the past, optimizing neural network structures often relied on highly experienced engineers to tune parameters. Can we directly let machines automatically search for network structures?

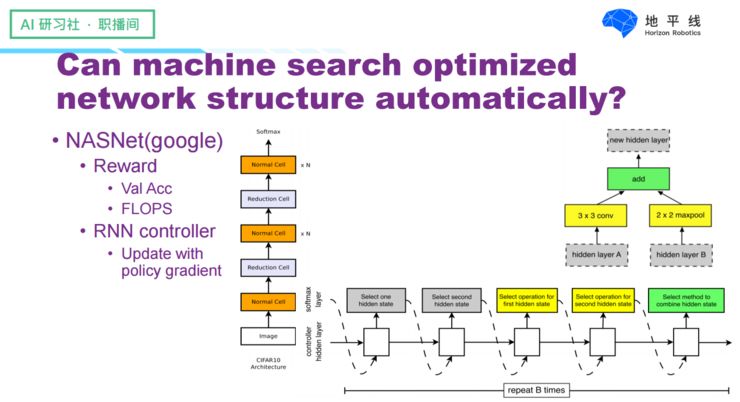

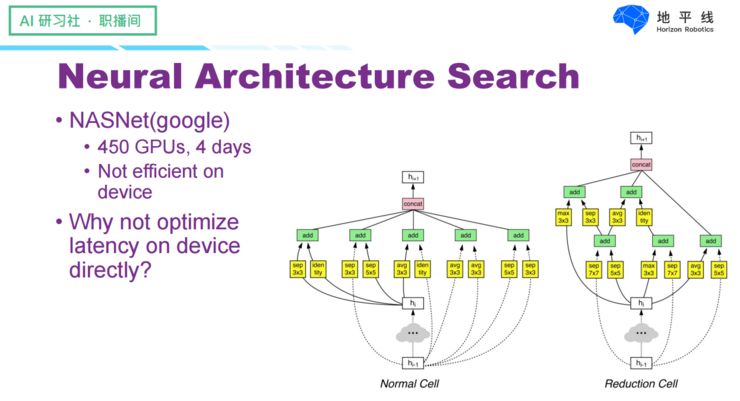

It is indeed possible; for instance, Google recently conducted a project called NASNet, which uses reinforcement learning to train a network structure generator by providing feedback based on image classification accuracy and the network’s computational load, allowing the generator to create better network structures.

Google’s work used about 450 GPUs and took 4 days to search for a network structure that performed well in terms of both performance and computational load. The two figures show the basic units of the network structure. However, based on our previous analysis, these two basic units are unlikely to run quickly due to their fragmented operations and many non-parallelizable operations. Therefore, considering real running speed is a more appropriate choice for searching network structures, leading to subsequent work called MnasNet.

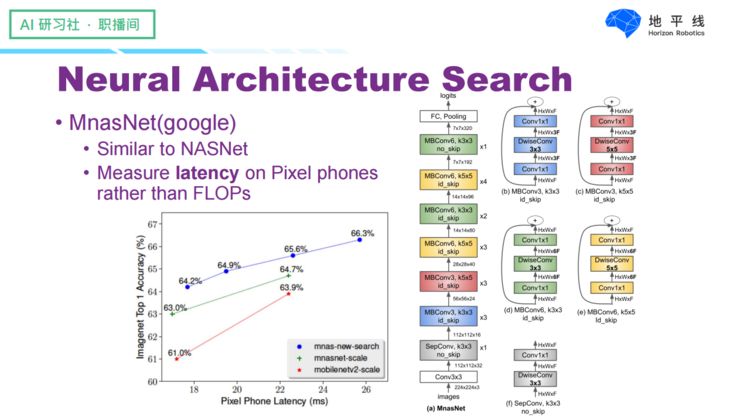

In this instance, Google directly used the running speed on mobile devices as feedback for reinforcement learning. We can see that the network structures generated using this method are much more reasonable, and their performance is slightly better than before.

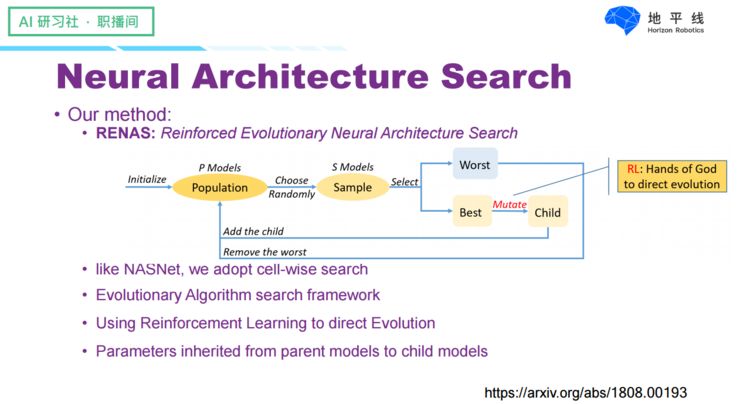

During the same period, we also conducted similar work—RENAS, which actually drew on NASNet but focused on solving the inefficiencies in the search process. Unlike NASNet, we used evolutionary algorithms to search for network structures while employing reinforcement learning to learn evolutionary strategies. The link to the work is above, and those interested can check it out.

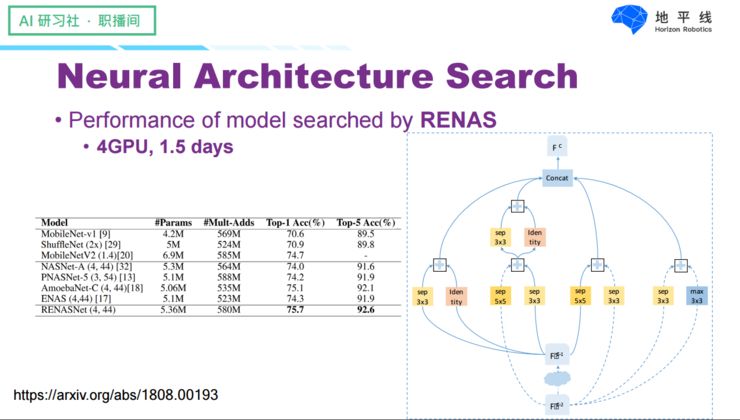

One advantage of RENAS is its significantly higher efficiency in searching for networks: we used 4 GPUs and 1.5 days to find a structure better than NASNet. However, its drawback, like NASNet, is that it used computational load as a metric, so the results it generated are only low in computational load but not necessarily fast in running speed.

Achievements of Algorithms and Hardware in Computer Applications

Having discussed so much, let’s finally showcase the application effects of optimized networks on mainstream visual tasks:

Common image-level perception tasks such as image classification, face recognition, etc., have relatively small inputs, so their overall computational load is not large, and the efficiency requirements for the network are not that stringent. However, for tasks beyond image classification, such as object detection and semantic segmentation, their inputs are much larger, often at resolutions of 1280×720 or even higher. The computational load of MobileNet or ShuffleNet at this resolution is still quite high. Moreover, in object detection and semantic segmentation, scale is a factor to consider, so when designing networks, we need to make additional configurations for scale issues, including introducing more branches and adjusting appropriate receptive fields.

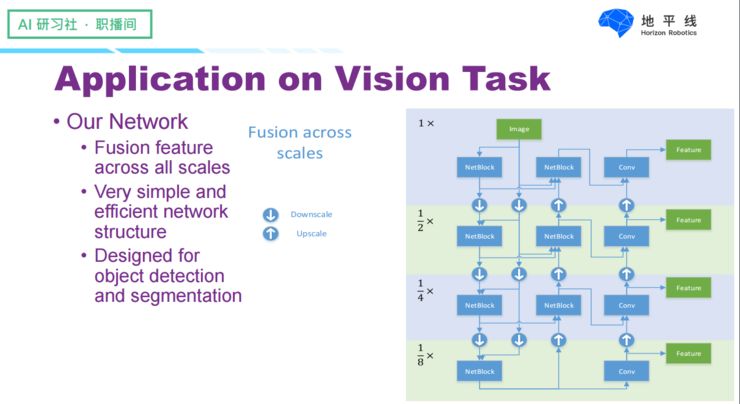

For object detection and semantic segmentation tasks, we have specifically set up a network structure, which is roughly illustrated in the right figure above. The key feature is that we have used many cross-scale feature fusion modules, enabling the network to handle objects of different scales. Additionally, the basic units of our network follow the principles of simplicity and efficiency, using the most hardware-friendly and easiest-to-implement operations to construct the basic modules.

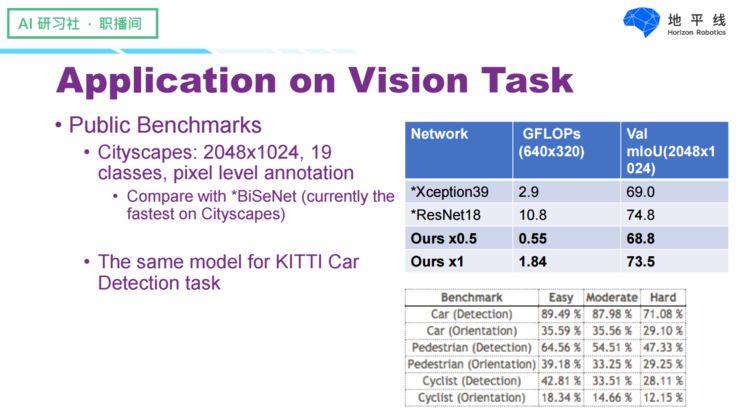

We have tested the performance of this model on some public datasets, mainly involving two datasets: one is Cityscapes, a semantic segmentation dataset with high image resolution, where the original image resolution is 2048×1024 and annotated with 19 classes. In these datasets, we compared our network with the latest paper BiSeNet, which is currently the fastest method found in the field of semantic segmentation. The computational model *Xception39 at a resolution of 640×320 requires approximately 2.9G of computational load, while our smaller model achieves almost the same effect at the same scale of input, requiring only 0.55G of computational load.

At the same time, in terms of performance—using mIoU as an indicator in semantic segmentation at a resolution of 2048×1024, our slightly larger network is very close to Xception39. Our network also underwent testing on the KITTI dataset, which has a resolution of approximately 1300×300, particularly excelling in performance for detecting cars and people, demonstrating a high cost-performance ratio compared to common methods like Faster RCNN, SSD, and YOLO.

Below, we showcase a demo of our algorithm implemented on the FPGA platform.

This network simultaneously performs object detection, semantic segmentation, and human pose estimation. The FPGA is also a prototype of our second-generation chip, which will tape out by the end of the year, with a single chip’s performance being 2-4 times that of this FPGA platform. This data was collected in Las Vegas, USA, where, in addition to human pose detection, we also conducted vehicle-mounted 3D keypoint localization, achieving real-time speeds, and it is also used as an important product in automotive manufacturing. This demo is just the tip of the iceberg of our work; we have many other directions we are pursuing, such as smart cameras and applications in commercial scenarios, aiming to imbue intelligence into all things, thus making our lives better.

[Excerpt from the Machine Learning Research Society]

Swipe lightly to follow~

If you find it good, please

Share

Share

Share