1Case Information

The patient is a 38-year-old married male. He was admitted on October 30, 2022, due to “burning sensation on the skin after sun exposure for over 30 years, jaundice, and abdominal pain for one week.” The patient reported that since childhood, he experienced a burning sensation on the skin of his hands and face after only a few minutes of sun exposure, which could result in erythema, papules, and crusting. Soaking in cold water alleviated the pain of skin lesions, and avoiding sun exposure for several days allowed the lesions to subside. He had multiple consultations at dermatology departments in other hospitals without a clear diagnosis. In October 2022, after taking “Amoxicillin and Ibuprofen” for “toothache,” he developed yellow urine and again experienced burning sensations on his face and hands after sun exposure. A few days later, the burning sensation improved, but erythema, papules, and crusting gradually appeared. One week before admission, he developed jaundice of the skin and sclera, accompanied by persistent severe abdominal pain, obstinate constipation, and difficulty sleeping. On October 29, 2022, a local hospital reported TBil 429.00 μmol/L, DBil 280.00 μmol/L, ALT 149.00 U/L, AST 161.00 U/L, GGT 465.00 U/L, and ALP 419.00 U/L. He denied any history of infectious diseases, occasionally consumed small amounts of alcohol, his spouse is healthy, and they have one child with no similar family history.

BMI 21.00 kg/m2, conscious, with normal calculation and orientation abilities, dark complexion, severe jaundice of the skin and sclera, no palmar erythema or spider nevi, no petechiae or bruising, and multiple erythema and papules visible on both hands, some of which had ruptured and crusted (Figure 1, 2). No abnormalities were found in the cardiopulmonary examination. The abdomen was slightly distended, soft, with tenderness in the upper abdomen, no rebound tenderness, the liver and spleen were not palpable, percussion revealed tympanic sound, and shifting dullness was negative, with decreased bowel sounds at 2 times/min. No abnormalities were found in the neurological examination.

Note: Multiple erythema and papules on the dorsal side of both hands, some ruptured and crusted.

Figure 1 Skin of the Hands (Acute Phase)

Note: No scarring or pigmentation left.

Figure 2 Skin of the Hands (Relief Phase)

Blood routine: WBC 5.56×109/L, Hb 104 g/L, PLT 30×109/L. Coagulation function: PTA 78.9%, INR 1.10. Liver function: TBil 379.20 μmol/L, DBil 341.06 μmol/L, Alb 37.00 g/L, ALT 113.10 U/L, AST 157.20 U/L, ALP 355.70 U/L, GGT 410.60 U/L, total serum bile acids 256.00 μmol/L. Iron metabolism: serum ferritin 86 ng/mL, serum iron 9.77 μmol/L, total iron binding capacity 34.97 μmol/L, unsaturated iron binding capacity 25.20 μmol/L. Lipid metabolism: LDL-C 3.05 mmol/L, TG 2.67 mmol/L. HAV IgM antibody, HBsAg, HCV antibody, HEV IgM antibody were all negative. EBV and CMV quantitative fluorescence were both <500 copies/mL. Autoimmune liver disease antibody spectrum (anti-mitochondrial antibody M2, anti-hepatocyte cytoplasmic type I antibody, anti-soluble liver antigen antibody, anti-pg210 antibody, anti-sp100 antibody, anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody), antinuclear antibody, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were all normal. Blood lead, ceruloplasmin, and IgG4 were also normal. An upper abdominal CT scan with enhancement showed: liver cirrhosis, splenomegaly, portal hypertension with collateral circulation formation, possible acute cholecystitis, and a small amount of effusion.

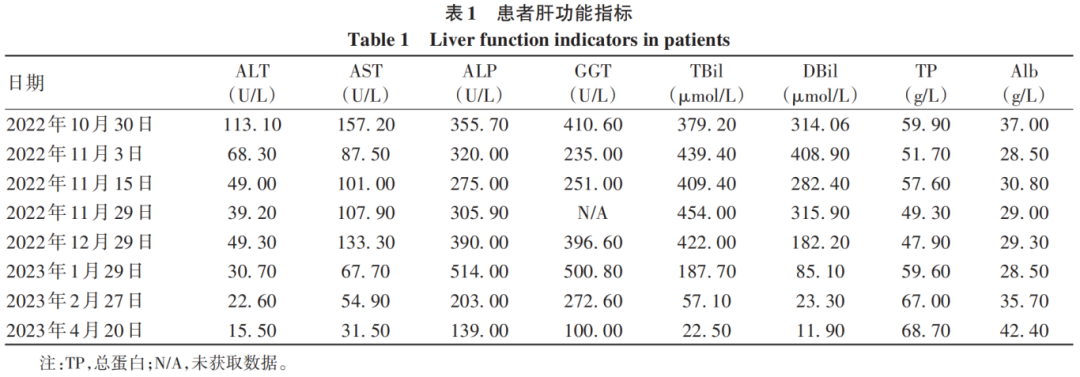

After admission, based on the patient’s medical history, physical examination, and auxiliary examinations, viral, autoimmune, alcoholic, and other common causes of liver cirrhosis were excluded, as well as rare liver diseases such as hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, and vascular liver diseases. The patient had a medication history before the onset of the disease, but it could not explain the cause of liver cirrhosis; the patient had a long history of non-bullous skin photosensitivity, severe abdominal pain, and obstinate constipation, which were not due to intestinal obstruction. Thus, it was considered that the patient had a hereditary metabolic liver disease, porphyria. The treatment included light avoidance, bed rest, pain relief, laxatives, ademetionine, reduced glutathione, cysteamine, ursodeoxycholic acid, and carbohydrate loading (oral or intravenous infusion of 300–400 g/d glucose), but the patient’s abdominal pain and constipation showed no improvement. On November 3, 2022, liver function was rechecked: TBil 439.40 μmol/L, DBil 408.90 μmol/L, Alb 28.50 g/L, ALT 68.30 U/L, AST 87.50 U/L, ALP 320.00 U/L, GGT 235.00 U/L. A liver biopsy was recommended, but the patient refused. Considering the patient’s critical condition, he was transferred to the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University for treatment, and genetic testing was sent out. The results indicated two heterozygous mutations in the ferrochelatase (FECH) gene: c.1078-1G>T (splicing) at chromosome position chr18:55218607, and c.951A>T (p.Glu317Asp) at chromosome position chr18:55221618, with the disease phenotype being erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP), inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. The diagnosis of EPP was confirmed, and symptomatic treatment showed no improvement. Liver transplantation was recommended, but the patient refused and was discharged. On December 1, 2022, he consulted at Xiangya Hospital of Central South University for symptomatic management and was again advised to undergo liver transplantation, which he still refused, and underwent plasma exchange therapy once, with no symptom improvement before discharge. After discharge, he took traditional Chinese medicine and ademetionine enteric-coated tablets, regularly rechecked liver function (Table 1), and the patient’s symptoms of abdominal pain, constipation, and jaundice gradually improved.

2Discussion

Porphyria is a class of hereditary metabolic diseases caused by a deficiency of enzyme activity in the heme biosynthesis pathway, leading to abnormal accumulation of porphyrins or their precursors in tissues, resulting in cellular damage. Based on the enzyme deficiency, it can be divided into eight types: X-linked protoporphyria, ALA dehydratase porphyria, acute intermittent porphyria, congenital erythropoietic porphyria, familial/sporadic late-onset cutaneous porphyria, hereditary coproporphyria, variegate porphyria, and EPP. According to clinical manifestations, it can be classified into acute neurovisceral porphyria, chronic bullous cutaneous porphyria, and acute non-bullous cutaneous porphyria. EPP belongs to acute non-bullous cutaneous porphyria, primarily characterized by burning sensations and significant pain on the skin within minutes of sun exposure. Its worldwide incidence is (5-13.3)/1,000,000, with less than 5% of cases combined with protoporphyria liver disease. This case, primarily presenting with acute abdominal pain and liver disease, is extremely rare.

EPP is a rare hereditary metabolic disease. Before the discovery of the FECH sub-allelic mutation IVS3-48T>C, EPP was considered an autosomal dominant hereditary disease caused by mutations in the FECH gene. The FECH gene encodes the last enzyme in the heme biosynthesis pathway, ferrochelatase (FECH); the sub-allelic mutation IVS3-48T>C can increase the application of abnormal splice sites, producing more easily degradable mRNA, leading to a reduction in FECH, i.e., a functional loss mutation of the FECH double alleles, causing FECH activity to drop below 30% of normal, resulting in excessive accumulation of protoporphyrin. Since the pathogenic condition is a functional loss mutation of both alleles, EPP is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease. The IVS3-48T>C gene mutation has an occurrence rate of about 10% in Caucasian populations and is more common in Asian populations. An epidemiological study in Japan indicated that the occurrence rate of the IVS3-48T>C gene mutation is about 45% in the Japanese population. Based on genetic analysis, it is recommended that the direct relatives of the patient undergo genetic testing. However, the patient’s relatives currently have no similar manifestations and due to cost issues, genetic testing has not been performed. The patient has a 6-month-old infant, and EPP often presents in childhood, with a 50% chance of the infant inheriting the father’s severe phenotype FECH mutation gene. Whether the infant will develop the disease depends on whether the mother carries the sub-allelic mutation IVS3-48T>C, which is more common in the Chinese population. Therefore, early genetic testing for his son and wife is beneficial for early diagnosis and intervention, improving prognosis.

Protoporphyrin is a photosensitive substance that, upon absorbing light energy, enters an activated state, producing a large amount of oxygen free radicals, leading to tissue damage through protein, lipid, and DNA peroxidation. Protoporphyrin is abundant in plasma and red blood cells, and due to its hydrophobicity, it accumulates in large amounts in the skin lipid layer, causing damage to vascular endothelium and skin tissue through oxidative processes. The liver is the only organ that excretes protoporphyrin; excessive accumulation of protoporphyrin in the liver can cause damage to hepatocytes and cholangiocytes, leading to reduced excretion of protoporphyrin and the occurrence of protoporphyric liver disease. Protoporphyrin damage is also observed in the nervous system, with mechanisms that remain unclear, possibly due to neurotoxicity of intermediates or derivatives in the heme biosynthesis pathway.

Due to a lack of understanding of EPP, clinical misdiagnosis and delays in treatment are common. A study involving 129 patients in the United States found that the average delay from symptom onset to final diagnosis of EPP was 13 years. This case was misdiagnosed and delayed for over 30 years, highlighting the need to increase awareness of the clinical symptoms of EPP. Based on its pathogenesis, the clinical symptoms of EPP mainly include: (1) acute non-bullous cutaneous photosensitivity reaction, characterized by burning and prickling sensations on the skin occurring minutes after sun exposure, lasting for hours to days, alleviated by avoiding sunlight, with prolonged exposure leading to papules, erythema, and crusting, with rare occurrences of vesicles or scarring. The first appearance of skin photosensitivity reactions often occurs in childhood; in one study, 76% of patients developed symptoms before the age of 4. (2) Liver function impairment. Liver disease in EPP is rare; protoporphyric liver disease is a cholestatic liver disease characterized by elevated transaminases and liver cirrhosis, which can lead to liver failure in severe cases. (3) Neurovisceral dysfunction, presenting as a syndrome due to abnormalities in the central, peripheral, and autonomic nervous systems, may manifest as acute abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, nausea, vomiting, intestinal obstruction, sensory abnormalities, fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, hallucinations, seizures, etc. Significant neurovisceral symptoms are termed acute episodes. Acute episodes and liver disease in porphyria often have triggers, such as medication, alcohol, smoking, hunger, and stress. EPP may also present with clinical manifestations such as cholelithiasis, vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis, and anemia.

Based on clinical manifestations, combined with family history, laboratory tests, increased porphyrin substances in blood/urine/stool, and genetic analysis results, a clear diagnosis can be made. It is important to note that in EPP and other porphyrias, total erythrocyte protoporphyrin and non-metal-containing erythrocyte protoporphyrin are elevated, while urinary porphyrin levels remain normal as protoporphyrin is not excreted through the kidneys. After sun exposure, urine does not turn brownish-red. Skin biopsy can help differentiate from other skin diseases, and liver biopsy can confirm protoporphyric liver disease. The typical manifestation of protoporphyrin accumulation in the liver is the characteristic birefringent “Maltese cross” seen under polarized light microscopy. EPP is an acute non-bullous cutaneous porphyria that needs to be differentiated from other photosensitive skin diseases such as solar dermatitis, summer dermatitis, and polymorphic light eruption.

The management of EPP mainly includes: basic prevention and treatment, prevention of acute episodes and liver disease. Basic prevention includes avoiding sunlight; when outdoor activities are necessary, physical and chemical sun protection is recommended, such as wearing sun-protective clothing and hats, and applying sunscreen. Some studies suggest that alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and β-carotene may increase patients’ tolerance to sunlight, both of which have been approved for the treatment of cutaneous porphyria. Another small-sample study found that cimetidine can reduce patients’ photosensitivity; among 15 patients followed, 11 patients experienced reduced photosensitivity during treatment. When skin porphyrias occur, cold compresses and analgesics can relieve pain symptoms. Due to a lack of sunlight, EPP patients often have vitamin D deficiency, requiring monitoring and supplementation of vitamin D. The occurrence of acute episodes and severe liver disease often has triggers; hence, it is important to avoid hunger, smoking, alcohol, and stress, as well as medications that can harm the liver. During acute episodes, supportive symptomatic treatment is provided, and intravenous infusion of chlorophyllin and carbohydrate loading therapy can relieve symptoms. Abnormal liver function should be evaluated for other pathogenic factors, reversible factors should be removed, and symptomatic liver protection should be administered. Treatments for severe liver damage include intravenous infusion of chlorophyllin, plasma exchange, and ursodeoxycholic acid. If these methods do not alleviate liver dysfunction, liver transplantation should be considered. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is the only curative method for EPP and can prevent recurrence of liver disease.

EPP is a non-lethal photosensitive disease with diverse symptoms. Through the study of this case, it helps enhance clinical physicians’ experience in diagnosis and treatment, fully recognizing that EPP can manifest in various forms such as skin photosensitivity, abdominal pain, anemia, and liver function impairment, striving for early diagnosis and standardized treatment to improve patient prognosis.

https://www.lcgdbzz.org/cn/article/doi/10.12449/JCH240323

Wu Zhendong, Zhou Guoqiang, Xiang Yan, et al. A Case Report of Erythropoietic Protoporphyria with Liver Cirrhosis [J]. Journal of Clinical Hepatobiliary Diseases, 2024, 40(3): 581-584